Technical difficulties: D.C. data shows how minor supervision violations contribute to excessive jailing

Using D.C. as a case study, we explain how much non-criminal – and often drug related – “technical” violations of probation and parole contribute to unnecessary jail incarceration.

by Andrea Fenster, October 28, 2020

Parole and probation violations are among the main drivers of excessive incarceration in the U.S., but are often overlooked policy targets for reducing prison and jail populations. Nationally, 45% of annual prison admissions are due to supervision violations, and 25% are the result of “technical violations” — noncompliant but non-criminal behaviors, like missing meetings with a parole officer. The sheer number of people held in jail for mere violations of supervision exemplifies the gross overuse and misuse of incarceration in the U.S.

Despite their impact on local jail and state prison populations, technical violations are not well understood, often appearing in the data simply as “violations” without any description of the underlying behavior. However, Washington, D.C. stands out by publishing a wealth of local jail data as well as contextual data from federal agencies like the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA), which offers a fuller story of what happens to people on supervision.

Given this abundance of data, we use D.C. as an illustrative example to explore excessive jail detention for technical violations, including what behaviors lead to violations, the extraordinary lengths of time people can be held for violations, and important demographic information showing that people on supervision face serious employment and housing barriers – which are only exacerbated when violations lead to re-incarceration. Following our analysis of D.C. technical violations, we discuss the problematic legal process underlying these violations.

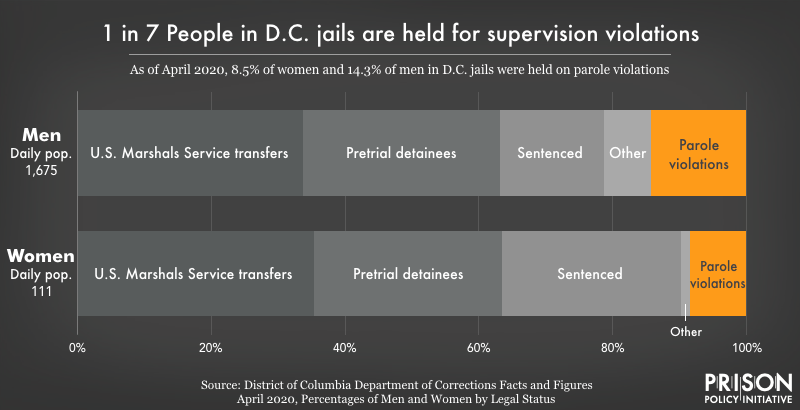

In the nation’s capital, the scope of the problem is conspicuous. The Washington, D.C. Department of Corrections estimates that 14.3% of all men and 8.5% of all women housed in the system are held as a result of a parole violation.1

How D.C.’s supervision system sets people up for revocation

When people serving a sentence from D.C. Superior Court are released from jail or prison, many remain under supervision of some form – either supervised release or parole. Each person under supervision must comply with certain conditions, which are monitored by a Community Supervision Officer (CSO). The same is true of those sentenced by a court to probation, another form of supervision, instead of a period of incarceration. The Robina Institute estimates that people on probation must comply with 18 to 20 requirements a day; the list of requirements in D.C. illustrates how easy it can be to “violate” these many conditions (see sidebar).

Enforcement of the often numerous and onerous conditions is left to CSO discretion. When someone under supervision does not meet one or more of their requirements, the CSO either decides to apply “graduated sanctions” – like more frequent drug testing, more frequent reporting, or curfew – or files an Alleged Violation Report (AVR). The AVR is the document that initiates proceedings against a person under supervision, which, if a warrant is issued, may result in a revocation hearing and ultimately, incarceration.

The system of supervision leads to inflated jails

In D.C., the second most common “most serious offense” for men in jail is a parole violation, just behind assault and ahead of weapons violations, drug offenses, property crime, burglary and robbery, and other violations of law. Among women, parole violations are the third most common “most serious offense.”2 The D.C. Department of Corrections (DOC) reported that, as of April 2020, 8.5% of women and 14.3% of men in jails were held on charges that included a parole violation or had a “Parole Violator” status.3

For context, we previously found that in both New York and Texas, parole violations made up just over 8% of those in jails statewide. In comparison to those states, D.C.’s jails hold a larger proportion of people on parole violations. However, when compared to the share of people held for supervision violations in other large cities like Philadelphia (58%), New York City (27%), and New Orleans (22%), D.C.’s incarceration for violations (about 14%) appears consistent with – or even more modest than – other cities’.

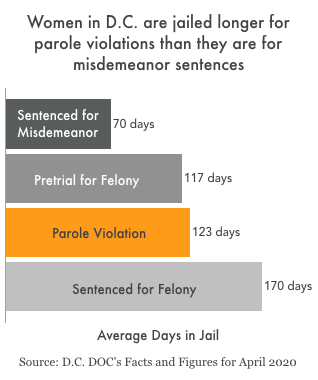

In more concrete terms, those percentages mean that roughly 250 out of nearly 1,800 people in D.C.’s jails4 are being held because they violated parole or are awaiting a revocation hearing. It is worth noting that, while the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA) officially reports that Alleged Violation Reports for technical violations usually do not result in revocation to incarceration, just because someone isn’t officially revoked doesn’t mean they won’t spend a long time in jail awaiting a hearing for that decision. For people in jail whose most serious (alleged) offense is a parole violation, the average stay is nearly 4 months.

Four months in jail is nothing to scoff at. And yet, on average, a woman in D.C. Jail on a parole violation is confined longer than one awaiting a felony trial and almost four times as long as those awaiting trial for misdemeanors. Even more egregious, jail time for women’s parole violations, on average, outlast even full sentences for misdemeanor convictions. Such extended periods of confinement are concerning because even much shorter periods of incarceration can result in severe consequences like housing and job loss, on top of the extreme loss of liberty, privacy, and self-determination inherent in incarceration.

Most violations are infractions for low level – and frequently non-criminal – offenses

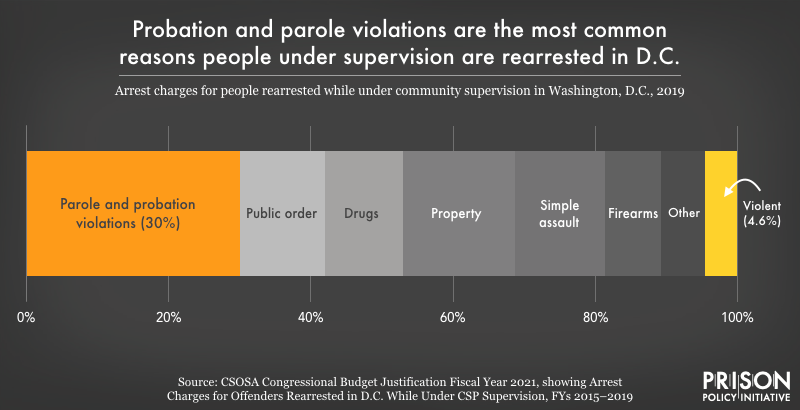

Frequently, people who are rearrested while on supervision are not arrested for a new crime, but are scooped up by the criminal legal system for entirely non-criminal behavior. In D.C., 30% of people who are rearrested while on supervision are arrested merely for violation of a condition of release.5

In contrast, less than 5% of rearrests were for “violent” offenses.

The large number of arrests for supervision violations is particularly frustrating when we look more closely at what these arrests are for. While the D.C. jail data does not include a breakdown of the underlying offenses for parole violations, data from the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA) about Alleged Violation Reports (AVRs) helps fill this gap. While not all AVRs lead to arrest and jail time, technical violations that land people in the D.C. Jail typically start with an AVR.

In 2019, just under half of the total population on supervision (7,217 out of 14,830 people) had violations that a Community Supervision Officer (CSO) deemed serious enough to warrant an AVR, initiating revocation proceedings.6 Of those AVRs, about 60% were for new arrests, 20% were for missing supervision appointments, and 20% were for other technical violations – many likely drug related, considering the overwhelming share of all technical violations related to drug tests.

CSOSA provides data on all technical violations – not just those that result in an AVR – and overall, drug related violations account for far more technical violations than any other offense type.7 In 2019, D.C. reported 96,528 total technical violations; over 90% (87,424) were drug related. While drug offenses are generally perceived as low-level offenses, even the term “drug related” may overstate the severity of these violations: over half were for not submitting a specimen for testing – not for failing a test, but simply missing a test.

For those on supervision who are struggling with substance abuse, the carceral “solution” forged by the parole system is counterproductive. It rips people from tangible supports like drug treatment and counseling, opting to criminalize individuals rather than taking a public health approach. People are then sent back to jail or prison, stifling any progress towards sobriety they may have made in the community.

Of the small portion of technical violations that were not drug related, most were for relatively trivial offenses: 3.1% were for not reporting to a Community Supervision Officer (CSO), 3% were for a violation relating to electronic monitoring, and less than 1% were for not cooperating with drug treatment. 2.4% were categorized as “other non-drug violations.”

Violations and revocations undermine community supervision goals

At least in theory, supervision after incarceration is meant to successfully reintegrate people back into society. CSOSA recognizes that the beginning of supervision is particularly challenging for those new to supervision. Yet their solution is merely to “stress the importance of complying,” threatening jail time instead of offering tangible supports for people on supervision who are facing so many other barriers. For example:

- Only half (52%) of those under supervision were employed. CSOSA estimated that less than two-thirds of the population under supervision was employable to begin with.8

- More than 1 in 4 (29.4%) people in the supervised population do not have a high school degree or GED.

- More than 1 in 10 (11.2%) people on supervision do not have stable housing.

Compounding the problem, jail time and revocations destabilize vulnerable people even further:

- Those who are revoked are far less likely to be employed, even if they were employable in the first place: only 17.4% of those revoked who are employable have work.

- Almost 45% of those who are revoked do not have a high school level degree.

- People who are revoked are more than twice as likely as those who were not reincarcerated to have unstable housing.

Even the system used to determine whether a violation occurred is seriously flawed

Incarceration for supervision violations is especially concerning because revocation hearings are much less formal than criminal proceedings and come with many fewer protections, despite the fact that periods of incarceration after revocation can exceed full sentences handed out by a court. For instance, while the criminal standard for conviction requires proof “beyond a reasonable doubt,” a finding of revocation needs only to be based on a “preponderance of the evidence.”9 Hearing examiners in revocation hearings can also consider evidence that would be inadmissible or might not reach the standards of credibility required in a criminal case.10 And there is no right to a jury despite the fact that most recommended sentences for revocations are over 6 months.11 For technical violations alone, sanctions can include up to 16 months of incarceration or extended supervision.

Even the guideline categories that recommend new sentences for different violations are problematic. The range of recommended periods of incarceration is based off of a “Salient Factor Score.” However, these scores are almost entirely based on a person’s past criminal record – a measure which people cannot change and only ever increases but never decreases. Because the score weights previous criminal records so heavily, only 0.4% of people fall into the lowest risk category and consequently the lowest recommended sentences. Compounding the problem are expedited revocation offers, which, in practice, are similar to coercive plea deals.12

The big picture

People in jail for technical violations – things that are not criminal offenses for people not under supervision – exemplify the overuse and misuse of incarceration. D.C. is just one criminal legal system among over 50 more in every state and territory. Dismantling mass incarceration is impossible without also addressing the systems that latch on to people involved in the criminal legal system and refuse to let go. To get the full picture, politicians, advocates, and scientists must take hard look at the many Americans under supervision and the ways that they are continuously churned through our massive criminal legal system. It is time to end these cycles of criminalization and find solutions that free people from the enormous reach of supervision.

Footnotes

-

The information in this briefing is based on the D.C. DOC’s Facts and Figures report from April 2020. The D.C. DOC put out a report with updated figures from July 2020 that shows the proportion of people held on parole violations as being lower than April. This is likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus is not necessarily representative of incarceration over time. It does, however, suggest that it is unnecessary to hold so many people in jail for parole violations. ↩

-

These rankings exclude men and women held by the U.S. Marshals’ Service (USMS) who are held in D.C. Jails for trials in the federal system. USMS holds account for 30% of the male population and 35% of the female population. ↩

-

The total number of people total who are charged with a parole violation may actually be higher, because it may not be their “most serious offense.” ↩

-

This estimate is based on the average daily population of the D.C. correctional system in FY 2020 and the percentages of “Parole Violators” reported in the D.C. DOC’s Facts and Figures for April 2020. More specifically, we estimate that about 240 of 1,675 men and 9 of 111 women were held at least in part on parole violations. ↩

-

On top of that, another 12% were arrested for “public order” offenses – things like DUIs, disorderly conduct, gambling, prostitution, traffic offenses, vending and liquor law violations, drunkenness, vagrancy, curfew, and loitering. ↩

-

There were 6,851 AVRs issued for those on supervised release and parole and another 366 for those on probation. The total supervised population was 14,830, meaning that just under half of the people on supervision, at some point in 2019, had an AVR submitted. ↩

-

There are eleven substances that the drugs tests measure, including alcohol and cannabis. Use of either substance, though it may not be illegal, may constitute a violation of release. ↩

-

Employability is determined by CSOSA by a job verification at the beginning of each person’s supervision period. CSOSA deems a person employable if they are not retired, disabled, suffering from a debilitating medical condition, receiving SSI, participating in a residential treatment program, participating in a residential sanctions program (i.e., incarcerated), or participating in a school or training program. ↩

-

Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is an exacting and high standard of proof. The jury instructions describe that it is absent of the kind of doubt that “would cause a reasonable person, after careful and thoughtful reflection, to hesitate to act in the graver or more important matters in life.” On the other hand, a preponderance of the evidence requires only that the fact is more likely true than not. ↩

-

In criminal court, judges use complex rules like the Federal Rules of Evidence to ensure that evidence used to convict a person is both reliable and credible. However, in revocation hearings, a finding of credibility or reliability is not required. Instead, hearing examiners can exclude evidence that is irrelevant or repetitious. Also, fewer constitutional protections apply, meaning that hearing examiners can review things that courts have excluded on constitutional grounds. ↩

-

In D.C. Superior Court, people who are charged with offenses that are punishable by at least 180 days of incarceration or a fine of $1,000 are entitled to have their cases heard by a jury. Cases that carry less than a maximum of six months’ incarceration are be heard and decided by a judge. D.C. Code S 16-705(b). ↩

-

These plea deals encourage people to admit guilt, even when they may be entirely innocent, in order to avoid going to a hearing or trial which might lead to even more time behind bars. ↩