New data on formerly incarcerated people’s employment reveal labor market injustices

Newly released data doubles down on what we’ve reported before: Formerly incarcerated people face huge obstacles to finding stable employment, leading to detrimental society-wide effects. Considering the current labor market, there may be plenty of jobs available, but they don’t guarantee stability or economic mobility for this vulnerable population.

by Leah Wang and Wanda Bertram, February 8, 2022

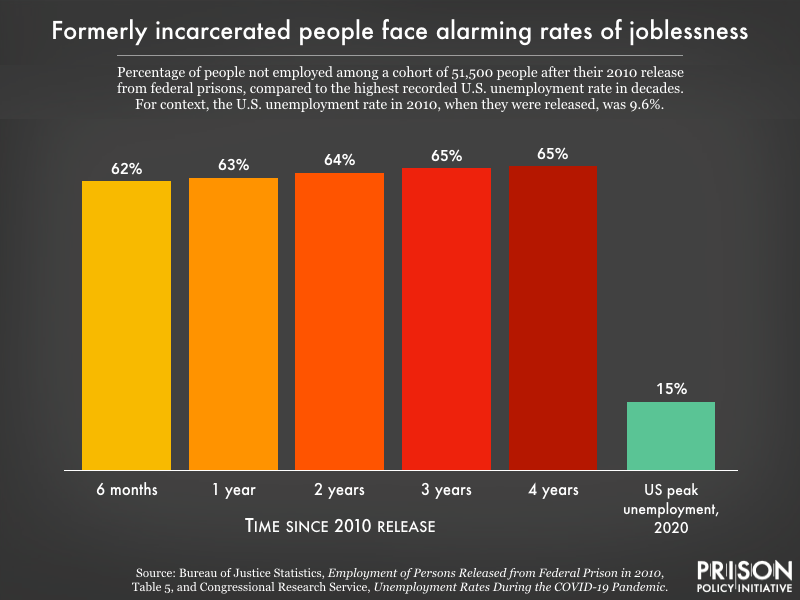

How many formerly incarcerated people are jobless at the moment? A good guess would be 60%, to generalize from a new report released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). The report shows that of more than 50,000 people released from federal prisons in 2010, a staggering 33% found no employment at all over four years post-release, and at any given time, no more than 40% of the cohort was employed. People who did find jobs struggled, too: Formerly incarcerated people in the sample had an average of 3.4 jobs throughout the four-year study period, suggesting that they were landing jobs that didn’t offer security or upward mobility.

We warn readers that we can’t call the 60% jobless rate an “unemployment rate” — joblessness is different from unemployment, which refers to people actively looking for work. We calculated the first and only national unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people in our 2018 report Out of Prison and Out of Work, and we can’t update that analysis, because we based it on data that the government only collected once.2 Nevertheless, the new BJS data suggest that employment rates among people who have been to prison aren’t improving.

Formerly incarcerated individuals tend to experience joblessness and poverty that started long before they were ever locked up. When they’re released from prison, the pressure is on to get a job: People on parole (or “supervised release”) often must maintain employment or face reincarceration,3 while struggling to access social services, and trying to make ends meet in a job market more hostile to them than ever before. This combination of pressures amounts to a perpetual punishment. And it’s not just formerly incarcerated individuals who are punished: Policies that weaken their ability to turn down jobs with low wages may depress wages for other workers in their industries, as we’ll explain in this briefing.

Harsh parole conditions, a lack of social welfare programs, and a tough job market are forcing formerly incarcerated people — already a low-income, majority-minority demographic — into the least desirable jobs. But not everybody is losing: Businesses have found a way to capitalize on the desperation of applicants with conviction histories and exploit the fact that these these individuals have less bargaining power to demand changes in conditions of employment, such as better wages benefits and protections. This results in lower overall wages and more harmful working conditions in certain industries.

Post-release, months of searching and moving between jobs is common

The overall employment rate over four years after the study population was released hovered between 34.9% and 37.9% — in other words, about two-thirds of the population were jobless at any given time.

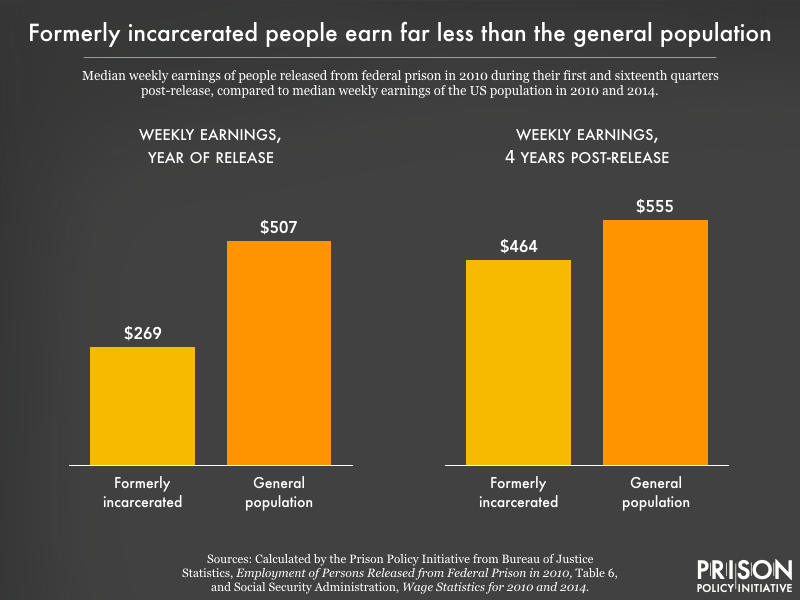

For those who did find employment after release, their earnings were lower than the general population: In the first few months, formerly incarcerated people were earning just 53% of the median US worker’s wage. And after four years of seeking and obtaining irregular employment, the study population was making less than 84 cents for every dollar of the US median wage (which, in 2014, was about $28,851 annually).

Earnings were lowest for Black and Native American people released from federal prison;5 in fact, racial and ethnic disparities in earnings seemed to grow over time. These findings probably reflect an unfortunate “racialized re-entry” process for people leaving prison, where the stigma of incarceration itself and differences in social networks for job-seekers vary across racial and ethnic groups. Researchers of this concept noted that white people getting out of prison actually appeared more disadvantaged and less employable “on paper” due to higher rates of substance use and longer sentences, but still ended up with better employment and income than Black and Hispanic people leaving prison.

Employment may be one of the most important benchmarks of reentry, yet it took formerly incarcerated people an average of over six months to find their first job after release. As such, many did not maintain employment over the entire four-year study period, and the average person in the study had 3.4 jobs over that time. If that sounds erratic, it is: The average person is employed for 78% of the weeks between ages 18 and 54, while people in the study’s cohort were employed just 58% of the time post-release. When people are moving from job to job, families and the economy suffer, and people risk violating their post-release supervision and being returned to incarceration.

Lastly, though it’s not clear exactly why, people who served less than a year in federal prison actually had a harder time finding and maintaining employment post-release, and spent more time without a job than the other groups.6 Given this devastating impact on their long-term employment prospects, it’s evident that people who are given short sentences — and who pose no safety risk — should not be incarcerated to begin with.7

The struggle to find a good job

The fact that most people released from prison have spotty, sporadic employment may mean that the jobs they’re getting are difficult jobs to keep, even for an extremely motivated worker. These could be temporary jobs, jobs where workers aren’t protected from wrongful termination, or dangerous or low-wage jobs that are unsustainable.

According to the BJS report, the major industries employing formerly incarcerated people include waste management services, construction, and food service. A 2021 study released by the U.S. Census Bureau affirms this finding. The study analyzed thousands of people with felony convictions, tracking their employment and income in the years around the Great Recession (2006-2018), and found that rebounds in construction and various service industries after the recession were associated with a bump in employment and income levels for these individuals. However, the people in that study saw their employment levels plateau after a few years, even in areas where construction and manufacturing thrived.

It’s true that industries like manufacturing and construction tend to boost employment and reduce recidivism for those leaving prison. But while these jobs did, at one time, allow people to build wealth and support a family, they don’t as much anymore, meaning that they are likely not alleviating poverty among formerly incarcerated people. The fact that formerly incarcerated people are not obtaining steady, reliable work is likely related to the industries in which they’re most commonly employed.

When the workforce is under mass supervision, key industries lose employee bargaining power

Looking more closely at the “low-skill” jobs that formerly incarcerated people tend to get can help us understand how mass incarceration and supervision may be hurting whole sectors of workers. In construction and manufacturing, union membership has declined significantly over the last twenty years.8 During the same period — between 2000 and 2019 — the number of people on parole grew by more than 150,000, and the number of people with felony convictions swelled from 13.2 million to an estimated 24 million.

While it’s impossible to draw a causal relationship between these two trends — given the numerous factors at play — there is serious potential for exploitation of formerly incarcerated people. For example, The New York Times has reported that New Yorkers with conviction histories are shuttled into non-union construction jobs with low to no benefits. Formerly incarcerated employees placed at such companies have described being “taken aback” at the low wages, and many have had to work other jobs to supplement their pay from their day jobs in construction.

A rising number of people with felony convictions — which is the result of, among other things, overly punitive sentencing — may be depressing wages and hurting working conditions for all workers in certain industries. Formerly incarcerated workers are not to blame, especially as many have likely been working in these industries for the better part of their adult lives. Prison does nothing to improve their qualifications as workers; meanwhile, the struggle of reentry makes them more desperate for job offers, as the new data make abundantly clear.

Formerly incarcerated people need greater opportunity from today’s labor market

The new BJS data confirm that formerly incarcerated people still suffer from sky-high jobless rates (despite evidence that virtually all want to work), and that those who do find work are getting unstable jobs. Formerly incarcerated people are typically poor before they go to prison, and joblessness during reentry can push them into even deeper poverty and have a permanent impact on their wealth accumulation.

These devastating statistics have implications for workers without criminal records as well. When industries can use vulnerable workers to replace or supplement workers who demand decent wages and benefits, the price of labor declines. When burdensome supervision requirements, unnecessary occupational licensing restrictions, and a lack of social welfare programs combine to make formerly incarcerated people desperate for work, all workers suffer.

Indeed, during the labor shortages we’ve seen in 2021 and 2022, employers are turning to currently or formerly incarcerated people as a convenient solution. (And sadly, a rising awareness of formerly incarcerated people’s unjust barriers to employment has allowed some of these employers to frame their actions as enlightened.) These shifts may manifest in depressed wages, benefits, and worker protections sector-wide.

People leaving prison need expanded access to job opportunities so that successful reentry can begin immediately and provide stability, not uncertainty. Policy solutions like occupational licensing reform and automatic record expungement, as well as “banning the box” on all initial employment applications, are respectable first steps. Even better would be including those with conviction histories as a protected class9 in employment non-discrimination statutes. In-prison training programs for jobs in construction and similar industries may also boost employment and wages in some areas, according to some research, but it’s not a universal solution, nor does it solve underlying problems of low educational attainment and economic immobility.

It’s critical that lawmakers support workers with and without criminal records who are working together to end the exploitative practices that hurt them all. Without leveling the playing field for formerly incarcerated people, not only will their jobless rates remain high, but self-serving employers will continue to benefit from a disposable labor pool, with detrimental impacts on everyone.

Footnotes

-

For a more appropriate comparison, it would be reasonable to use the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ U-6 rating, which is a more inclusive measure of unemployment that includes people marginally attached to the labor force and those who want full-time work but have been forced to accept part-time work. Of available data going back to 1994, the average annual U-6 rating peaked in 2010 at 16.7%, and in 2020 the U-6 rating averaged 13.6%. More on alternative measures of unemployment can be found here. ↩

-

For more on how the jobless and unemployment rates compare, see the appendix of our 2018 report. ↩

-

Requirements that people on community supervision maintain or look for a job exist in several jurisdictions, including the federal supervised release system, Washington D.C., Louisiana (see footnote 4 of the Columbia University Justice Lab’s report Less Is More in New York), and Massachusetts. ↩

-

Pre-incarceration joblessness was consistently highest for Black, Native American and people of “Other” race or ethnicity. In the quarter prior to admission to prison, Black people were 87% jobless. Women had slightly higher levels of employment than men both before and after serving time in federal prison; however, they consistently earned lower wages. ↩

-

The methodology of the BJS report may have led to skewed findings about employment outcomes for Hispanic people: Researchers used Social Security information to link prison records to employment records. While all other race and ethnicity groups had 91% or more released people’s records successfully linked, only 45% of Hispanic people in the release cohort had their prison records linked to employment data for analysis. Therefore, the study doesn’t describe the typical employment experience of numerous Hispanic people who make up a large swath of US residents that never receive Social Security benefits. ↩

-

For those who served 1 year or less in federal prison prior to their 2010 release, it took the longest time on average to secure their first job (2.9 quarters, or almost 9 months). Additionally, their first job had the shortest average duration (18 months) and their overall employment rate over four years post-release was the lowest compared to those who served longer sentences. See Table 4 of the BJS report. ↩

-

Another recent paper provides evidence that diverting people from incarceration may mitigate some of the harsh impacts on employment discussed in this briefing: Researchers compared the employment outcomes of people released from prison compared to people with felony convictions only (some of whom went on to spend time in prison). Those in the prison-release cohort had lower employment and income levels over several years compared to those with felony convictions. ↩

-

In 2000, 18.3% of people employed in the construction industry and 14.8% of people employed in the manufacturing industry were members of a union, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’s Union Members In 2000 report. In 2019, by contrast, 12.8% of people employed in construction and 9% of people employed in manufacturing were members of a union, according to Union Members — 2019. (Bureau of Labor Statistics “Union Members” reports from the intervening years show a slow downward trend in union membership in these industries.) These represent slightly steeper declines than the overall U.S. workforce saw during that same period (13.5% in 2000 versus 10.3% in 2019). However, it’s worth noting food service doesn’t show the same decline; union membership rates in food service have hovered around 1% for the last couple decades. ↩

-

A couple of relevant state-level victories were summarized in a new report from the Collateral Consequences Resource Center: Illinois, Louisiana, New Mexico and Maine were among states that passed legislation in 2021 making it much harder for employers to discriminate against those with criminal records. ↩

Almost 20 years ago I did a study using data on Iowa clients under community supervision. The unemployment rates and under employment (seasonal) rates were large and there was a large fraction on disability.

At that time they were in a Social Security District where lost their social security benefits and they had to get assistance to get them restored.

Retribution does not end when they complete their sentence.

The younger you are when you get out of prison, the more likely you are to “reinvent” yourself in the job market. I knew of two people who spent a lot of time locked up as youths and young adults. One ended up becoming a psychiatrist, the other one got a good job at a moving company and later married and had a family.

Unfortunately, with a felony on their record and many years out of the work force, it is often very hard for those parolees over 30 to find employment that pays a living wage.

I agree with the last comment, punishment doesn’t end when someone is released.