Please Mr. Postman: It’s time to create a special postal mail rate for incarcerated people

Congress has created reduced postage rates for special groups in the past...it's time for it to create one for incarcerated people and their families.

by Stephen Raher, August 17, 2022

Between paying bills online and the convenience of “forever stamps,” it’s probably been a while since most readers have thought about the cost of mailing a letter. But for someone in prison, it could take six hours of work to pay for one postage stamp — and that cost is about to go up even higher.

In 2020, the US Postal Service obtained the legal authority to raise first-class postage rates faster than the rate of inflation (previously, rate increases had been capped at the consumer inflation rate). The following year Congress directed the Postal Regulatory Commission to study how this new rate structure impacts consumers. We submitted comments last month in conjunction with the Commission’s study, explaining how high mailing costs hurt incarcerated people and their families.

Not only are postal rates a substantial burden for someone earning 10 cents an hour, but incarcerated people depend on the mail much more than the average person does in today’s online world. As we explain in our comments:

Mail is the primary channel by which people in prison and jail can conduct personal business. Incarcerated people must still use paper for basic activities that have migrated online for many segments of society — activities like filing tax returns… submitting documents in judicial proceedings; monitoring credit reports for purposes of preventing identity theft; staying on top of personal finances; and laying the groundwork for post-release jobs or educational programs.

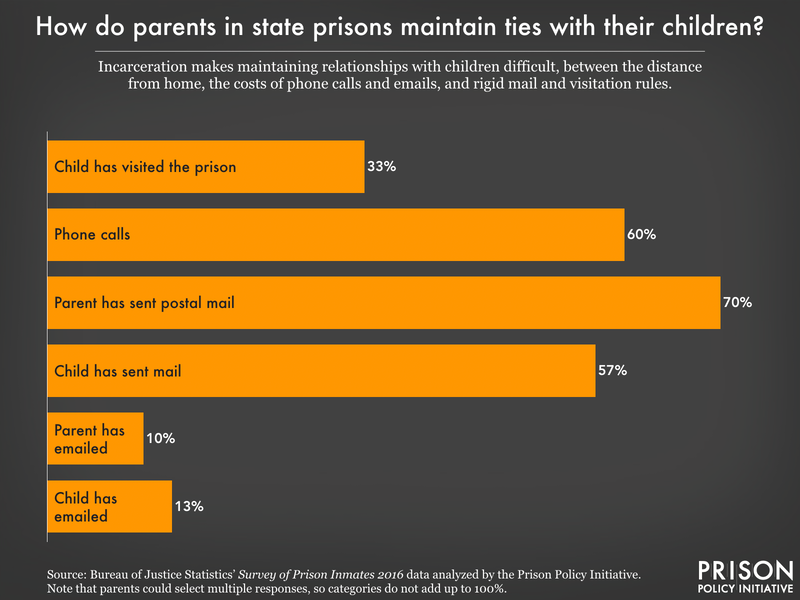

Mail is also crucial for incarcerated people to maintain family ties. Mail is the most common way that people in state prisons with minor children keep in touch with their kids, according to recently-released BJS data:

Disappointingly, Postmaster General Louis DeJoy recently announced his intent to seek yet another rate hike in the coming months. DeJoy cites inflation as the justification for another price increase. But while the average person who only mails a few letters or bill payments each month might be able to afford an extra 3-5 cents per stamp, this is a substantial burden on incarcerated mailers. While wages in general may inch up in an inflationary era, wages for incarcerated workers are stagnant:

In 2017, PPI surveyed prison wages in all 50 states and discovered that wage scales for people incarcerated in state prison systems average 14 cents to 60 cents per hour for standard prison-based jobs.

When researchers at the ACLU and the University of Chicago Law School conducted a similar survey in 2022, they reported virtually unchanged wages, with averages ranging from 13 cents to 52 cents per hour.

Raising postal service rates for incarcerated people will make it harder for families to stay in touch and for incarcerated people to prepare for their release, while sapping the little money they are able to save at their prison jobs.

Needless to say, the Commission should reconsider its order that allows the Postal Service to increase rates faster than inflation, but there’s another long-term step that would protect incarcerated people and their families from the disproportionate impacts of postal price hikes. Throughout American history Congress has created special reduced postage rates for special groups like periodical publishers, nonprofit organizations, agricultural groups, libraries, and blind people. Postal rates today may be less of a concern to the population-at-large than in years past, but it’s time for Congress to create a special rate classification for people who truly depend on postal communications — people in prison or jail and the family members who write to them.

The world of prison communications is already rife with burdensome restrictions and exploitative telecom charges that make it harder for families to stay connected. A special reduced rate for mail to or from incarcerated people is necessary now to protect the oldest, most reliable form of communication incarcerated people have.