New data confirms that prisons neglected COVID-19 mitigation strategies, putting public health at risk

New data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics summarizes state policies and prison population changes from March 2020 to February 2021

by Emily Widra, October 13, 2022

The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ August 2022 report Impact of COVID-19 on State and Federal Prisons, March 2020-February 2021 examines an inventory of measures each state prison system took to mitigate COVID-19, ranging from policies to reduce prison populations to efforts to provide vaccines and hand sanitizer to incarcerated people. The data reinforces what we already know about correctional settings during the pandemic: although crowded living spaces like prisons are generally hotspots for infection transmission, only some departments of corrections followed guidance from medical professionals, public health officials, and the CDC, while others ignored even the most basic recommendations. Below, we summarize the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ findings about state responses to various mitigation tactics and compile key findings about slowing prison admissions, increasing prison releases, testing for the virus, altering housing placements to prevent spread, and providing face masks.

Reducing prison admissions

In response to the recommendation from public health officials to reduce prison populations in the face of COVID-19, many jurisdictions slowed — and even temporarily suspended — prison admissions. Some departments of corrections responded relatively quickly: From January 2020 to April 2020, the number of people admitted to prison in Virginia, Tennessee, New York, Illinois, Michigan, and the federal Bureau of Prisons decreased by more than 90%.

On the other hand, some states responded particularly slowly to calls to reduce prison admissions: By April 2020, 14 states had only reduced their admissions by 45%. By September 2020, three states – Louisiana, South Carolina, Wyoming – were admitting more people to prison than they did before the pandemic.

January 2021 was the deadliest month of the pandemic: 60,000 people died of COVID-19 in the U.S. That same month, Wyoming admitted more people to state prison than they did in January 2020, before the pandemic. Just one month later, three more jurisdictions followed suit: more people were admitted to federal, North Dakota, and New Mexico prisons in February 2021 than in January 2020.

Expediting prison releases

Public health agencies advised prisons not just to slow admissions, but to release more people (particularly immunocompromised people) who were already inside. The new report shines a light on the extent to which prisons followed this advice. Unsurprisingly, the report shows that many states failed to actually use these expedited release policies to their intended effect. For example, although Illinois, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Vermont each had an expedited release policy, these departments of correction did not actually release anyone under these policies. In 10 states with expedited release policies, less than 5% of releases from January 2020 to February 2021 were expedited. An additional 21 states did not even have a policy for expediting releases from prisons during the pandemic.

Other states made better use of their expedited release policies to significantly reduce the number of people behind bars. Iowa appeared to make the most of their expedited release policy: 5,272 people were released from January 1, 2020 to February 28, 2021, 89% of which were expedited releases (4,700). There were other states where expedited releases were a significant portion of their total releases as well: New Jersey (36% of releases were expedited), Utah (31%), California (27%), Virginia (20%), and Arkansas (17%). Of course, every state could have gone further to safely release more people, but these states did at least the minimum in facilitating earlier releases amid an unprecedented public health emergency.

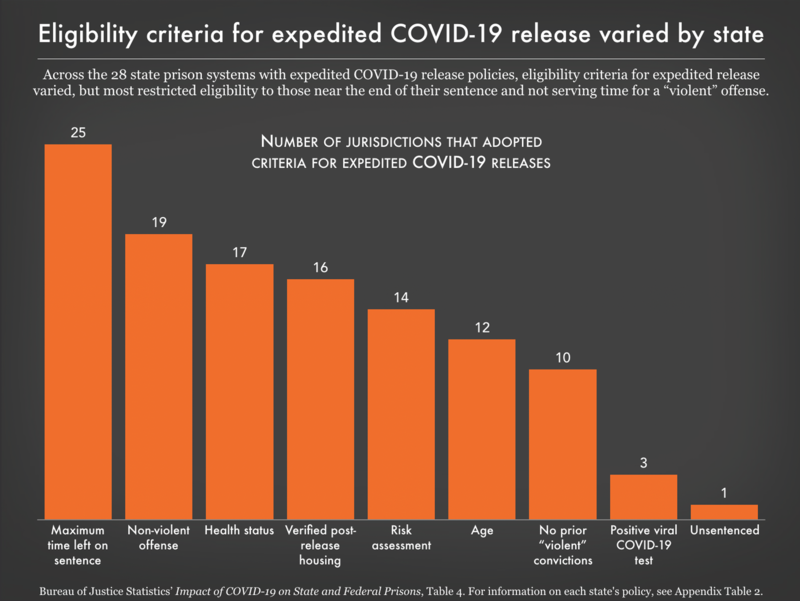

The new report also includes data on the measures that each jurisdiction used to determine eligibility for expedited releases. These criteria included offense types, health status, age, risk assessment scores, verified post-release housing, and time left on sentences. Across the 28 states that had a policy for expedited release, the combination of criteria required for eligibility varied greatly:

The Bureau of Justice Statistics asked departments of corrections about nine different criteria they might have used to determine who was eligible for expedited release. Some of these criteria, such as age, health status, and positive viral COVID-19 test were grounded in health logic: Older people and people with preexisting conditions were at higher risk of serious illness, and of course people who tested positive for COVID-19 were both at risk of serious illness and spreading the virus to others. But at least as many of these criteria, such as maximum time left on sentence, “non-violent” offense, and no prior “violent” convictions, were grounded in carceral logic that assumed the public safety risk posed by many incarcerated people, if released, would outweigh the extreme health risk these individuals were sure to face in prison during this health emergency.

These criteria for early release rely on tired stereotypes about incarcerated people, particularly that there are clear distinctions between “violent” and “non-violent” offenses and that people who have been convicted of “violent” offenses will pose a greater risk to society if released. In reality, we know that distinctions between “violent” and “non-violent” offenses are blurry and misleading. Further, those who are convicted of “violent” offenses are re-arrested at lower rates than those convicted of “non-violent” offenses. These offense-based eligibility criteria therefore reflect a continued commitment to punishment over health and safety, even in the midst of an unprecedented viral pandemic.

Interestingly, the data show that states that used a narrower set of eligibility criteria did not necessarily expedite fewer releases. Massachusetts, Montana, North Dakota, New Jersey, and Iowa all had high thresholds for eligibility. In spite of their inclusion on this list, Iowa and New Jersey expedited the highest percentages of their releases among all 50 state departments of corrections and the federal prison system in the time period studied. Meanwhile, Colorado used all nine of the criteria listed, yet only expedited about 6% of their releases from January 2020 to February 2021. We conclude that the data in this report show no clear correlation between how restrictive a state’s criteria were for expedited releases and the percentage of the state’s releases that were expedited. These inconsistencies across states’ expedited release policies, criteria, and actual implementation reveal a lack of foresight that departments of corrections must adjust in advance of future public health emergencies.

Testing for COVID-19

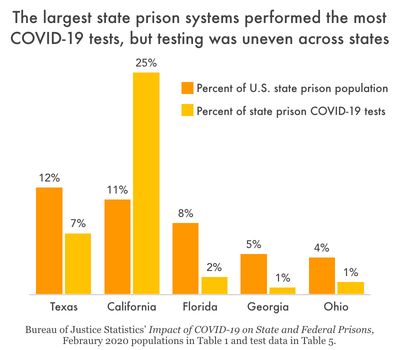

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that COVID-19 testing protocols and frequency varied greatly between states and facilities, which both exacerbated the public health situation and hindered efforts to measure the pandemic’s spread. California and Michigan were responsible for 38% of all COVID-19 tests of people in state prisons, even though these two states held a combined total of just 14% of the country’s state prison population as of February 2020. Meanwhile, Texas held 12% of the country’s state prison population in February 2020, but only accounted for 7% of tests administered to people in state prisons from January 2020 to February 2021.

The broad disparities between testing strategies makes it challenging to compare rates of COVID-19 infection between states. States that tested people more than once (indicated by more tests administered than people in prison) — such as Vermont and New Jersey — tended to have lower positivity rates, while states that performed fewer tests (likely only testing people who were symptomatic or had known exposures) tended to have higher positivity rates. Seven of the 10 states with the highest positivity rates (Mississippi, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Kentucky, Indiana, and Florida) performed fewer tests than the number of people in prison; clearly, not everyone in prison received a COVID-19 test.

The differences in testing strategies across states also had grave consequences for public health. Research from the Council on Criminal Justice in April 2021 found that states that did not use a mass-testing strategy (testing everyone at least once) in prisons actually had COVID-19 death rates at nearly eight times the death rate for non-incarcerated populations similar in age, gender, and race and ethnicity. But in states with mass testing, this disparity in death rates was halved. The number of tests performed in each state prison system included in this new report suggests that many states failed to heed the evidence that mass testing and retesting allows for better mitigation and ultimately better public health outcomes.

Other tactics to reduce transmission

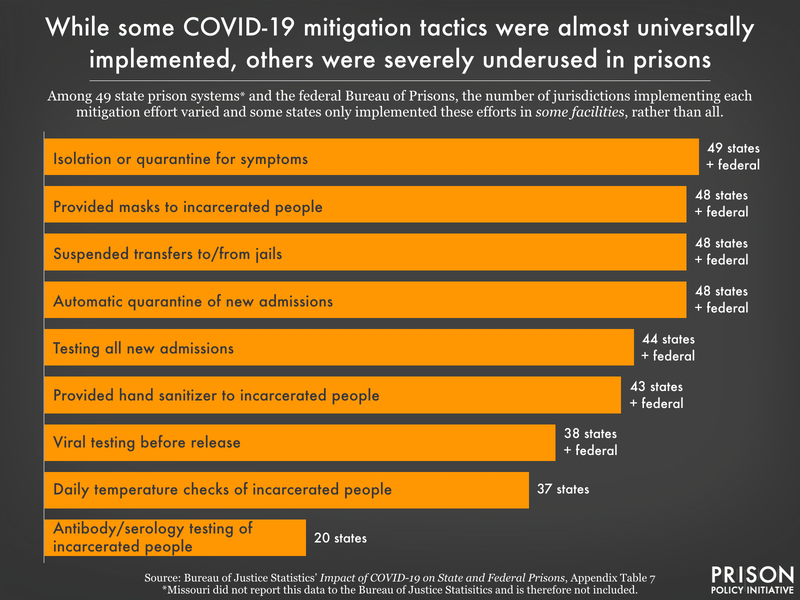

In addition to reducing the incarcerated population and tracking the spread within that population, prison systems used a variety of other tactics to slow the spread of COVID-19 in prisons. The report includes information about these tactics, some of which were implemented in every prison system in the country: staff temperature checks at the start of the shift, quarantine of symptomatic prison population,1 and providing face masks to incarcerated people and prison staff.

But many states missed opportunities to mitigate COVID-19 with obvious and simple interventions; moreover, the report finds inconsistent practices between facilities within the same prison systems. Nebraska, New York, Oklahoma, and Texas did not test new admissions to prisons, and six more states only tested on admission at some facilities. Nine states did not test people before release from prison, and an additional seven states only tested people before release at some facilities. We know that the transmission of COVID-19 between prisons and the surrounding communities is significant, so why, once testing became widely available, would departments of correction not test people leaving the prison and returning to the community?

Beyond testing, some states didn’t even take the minimal step of providing hand sanitizer: Nebraska, Connecticut, Georgia, and Tennessee. In Delaware, Hawaii, and Utah, hand sanitizer was only available at some prison facilities in the state. The successful distribution of hand sanitizer in all 43 other state prison systems and the federal prison system discredits concerns that alcohol-based hand sanitizer would not be safe in a prison environment.

Programming, in-person family visitation, and legal visitation were restricted across the country at various points during the pandemic. Twenty-three state prison systems suspended educational programming, drug and alcohol treatment, job programs, family in-person visits, legal visits, and religious programs. The federal Bureau of Prisons suspended all of those programs except for religious programming in some facilities. All 50 states and the Bureau of Prisons suspended some variety of these in-prison visits and programming. Only one state — Minnesota — did not universally suspend family in-person visits, though these visits were suspended at some facilities in the state.

It’s worth noting that 14 of the prison systems that suspended all programming and visitation also did not have any expedited prison releases. While it was important to limit transmission in group settings, it’s bad policy to sacrifice incarcerated people’s well-being by suspending visits while ignoring much more impactful strategies like reducing the population through expedited release. The impact of increased isolation and forgoing job training and educational programming (which can improve post-release outcomes) was a heavy toll to weigh against the physical health benefits of this mitigation tactic. And because it isn’t included in the report, we do not know if prison systems made any effort to provide resources to supplement in-person programming, especially in the critical period before vaccines were made accessible to incarcerated people.

Rolling out vaccines

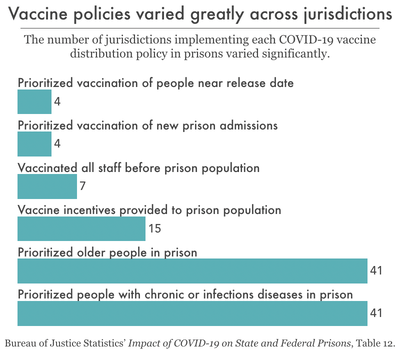

The Bureau of Justice Statistics collected information on vaccine distribution policies in all 50 states and the federal Bureau of Prisons. Additional findings include that no jurisdictions mandated (or explicitly barred opting out of) vaccinations for staff or prison populations.

When states drafted their vaccine plans in December 2020, we knew that by any reasonable standard, incarcerated people should have ranked high on every state’s priority list. At the time, congregate living settings (prisons, jails, colleges, nursing homes) were high-risk environments and the case rate in prisons was four times higher than the general population. While most states (40) did address incarcerated people as a priority group at some point during the vaccination rollout plan, it was not always particularly clear how incarcerated people — and correctional staff — were categorized for vaccine prioritization. This meant that incarcerated people in some states and facilities were offered the vaccine weeks or months late.

As an illustration of the broad disparities in vaccine rollouts across states, by February 2021, some jurisdictions (Bureau of Prisons, New Mexico, and Alaska) had made the vaccine available to prison populations and staff for more than 70 days, while other state departments of correction (Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina) had not yet even received – let alone started administering – the vaccine by February 28, 2021.

Disorganized and inconsistent vaccine rollout strategies showed that distributing vaccines equitably to incarcerated populations was not a priority, at both the national and state levels. As of February 2021, Alaska, Oklahoma, Michigan, and South Dakota had access to the vaccine for more than three weeks, but had not yet vaccinated a single correctional staff member. Similarly, the vaccine was available for more than three weeks in Arkansas, Maine, Tennessee, West Virginia, Arizona, and Oklahoma without a single incarcerated person receiving a dose. Some of these states are still struggling to increase the number of people vaccinated across the state (not just in prisons), but for departments of corrections to report zero vaccinations after three weeks of availability is a frightening display of indifference to the lives of incarcerated people and correctional staff.

Conclusion

Throughout the first year of the pandemic, it’s clear that many state departments of corrections ignored clear advice to mitigate the virus’s spread: reduce prison populations; increase prison releases; provide masks, hand soap, and hand sanitizer at no cost; utilize appropriate medical isolation (not solitary confinement); expand the use of screening tools (like temperature checks); expand testing of people in prison and staff to universal testing; conduct pre-release testing; prioritize incarcerated people and correctional staff in state vaccination plans; and improve vaccination rates among incarcerated people and staff. While the Bureau of Justice Statistics has yet to publish COVID-19 response data from the last 19 months, reporting from other sources indicates that many jurisdictions’ responses to COVID-19 in prison did not become more comprehensive or expansive as COVID-19 restrictions loosened outside of prisons.

While the newest data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows us evidence of what we observed — state departments of corrections failing to implement even the most obvious mitigation efforts — the data do not give us a full picture of the consequences of these shortcomings. Because of the inconsistencies between departments’ testing protocols, it is challenging to conclude that states that were better about implementing public health measures saw lower infection and mortality outcomes than states that didn’t. Consequently, the truth about just how bad conditions were in certain state prison systems remains obscured. Along with improving and expanding virus mitigation tactics, standardizing data collection practices is an essential next step. Implementing clear public health emergency response policies and enhancing departments of corrections’ transparency about virus prevention and outcomes is necessary in order to keep incarcerated people safe and healthy.

Footnotes

-

The first step in responding to the pandemic should have been to reduce the prison population as much as possible because prisons are no place for viral diseases. However, given the barriers to quick prison releases (like slowed court systems), departments of corrections inevitably needed to implement medical quarantine for sick people to reduce transmission. However, medical quarantine is not solitary confinement (which we know presents its own host of mental and physical health risks) but instead requires certain criteria to be met, including access to medical care. For more information on the difference between medical quarantine and solitary confinement, see this fact sheet from AMEND at the University of California San Francisco. ↩