Aging alone: Uncovering the risk of solitary confinement for people over 45

We estimate that more than 44,000 people 45 and older experience solitary in state prisons each year. As prisons continue to get grayer, policymakers must understand that denying older incarcerated people access to sunlight, exercise, and interaction with other people and spaces is both inhumane and fiscally irresponsible.

by Lucius Couloute, May 2, 2017

Recently released research finds that thousands of older incarcerated people are being forced to live in some form of solitary confinement on any given day. The practice of cutting human beings off from human contact is widely condemned, but this practice is particularly troubling since it means we are subjecting a large number of older adults to living conditions that can cause or exacerbate serious medical conditions. As prisons continue to get grayer, policymakers must understand that denying older incarcerated people access to sunlight, exercise, and interaction with other people and spaces is both inhumane and fiscally irresponsible.

‘Solitary confinement’ is, in fact, a highly contested term; some prison systems deny that they employ solitary confinement and prefer lighter, more administrative-sounding phrases such as SHUs (special housing units) or SMUs (special management units). Terminology aside, these units mean segregation from the rest of the prison population and people are typically forced to remain in their cells for over 22 hours a day with minimal human interaction. Solitary confinement is used at the discretion of correctional staff for a variety of reasons, ranging from punishing (or protecting) individuals, to housing people when other, normal, cells are not available.

Whatever name it’s given, and whatever the reasons for putting people there, the evidence is clear that solitary confinement causes undeniable harm and can create a host of negative psychological issues for all people including:

- Anxiety

- Hallucinations

- Withdrawal

- Aggression

- Paranoia

- Depression; and even

- Suicidal behaviors

From academics to Supreme Court Justices, and even the United Nations, the use of solitary confinement has drawn substantial criticism and is widely considered inhumane, especially for vulnerable groups such as the mentally ill and juveniles. But there’s another group whose lives are put in danger when they are forced to live in extreme isolation – older incarcerated people.

Because older adults are more likely to have chronic health conditions such as heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and lower respiratory disease, solitary confinement puts their long-term physical and mental wellbeing in danger. For the 73% of incarcerated people over 50 who report experiencing at least one chronic health condition, solitary confinement is especially hazardous.

Until now it’s been difficult to pin down exactly how many older adults are forced into solitary confinement each year, but a new report provides some answers. Based on survey data from 41 states, researchers from Yale and the Association of State Correctional Administrators find that over 6,400 men and women age 50 and older are living in some form of restrictive housing on any given day. (The survey’s definition of restricted housing includes all individuals housed in their cells for 22 hours per day or more for at least 15 days.)

But while 6,400 people is substantial, this number is just a snapshot and doesn’t reflect all of the older incarcerated people who have experienced the harm of solitary during a particular year. Using two Bureau of Justice Statistics reports, I estimate that more than 44,000 people 45 and older experience solitary in state prisons each year.1 This is more than the entire prison populations of countries like Canada, Australia, and El Salvador.

The obvious conclusion is that solitary isn’t some rarely used method of punishment, only used for younger, more threatening “offenders”. It’s the norm – even for older folks.

The effects of solitary on older people can be dangerous. According to Dr. Brie Williams of the University of California, solitary confinement increases the risk that older incarcerated people will develop or exacerbate chronic health conditions:

- A lack of sunlight can cause vitamin D deficiencies and greater risk of fractured bones

- Sensory deprivation from prolonged confinement in an empty room can worsen mental health and lead to memory loss

- Limits on space hinder mobility, which is crucial for maintaining health through exercise.

Unfortunately, there is no publically available data on why people are put into solitary, nor do we have good information on specific conditions and outcomes related to the practice. This data shortage is, in large part, because prison officials do not want their widely-used strategy to be studied in the light.

Luckily, people are beginning to take notice. Last year, spurred by public campaigns against the practice, President Obama banned the use of solitary confinement for juveniles and people who commit low-level infractions in federal prisons. But these limited reforms have not translated into widespread changes in the way we treat incarcerated people who are older and thus more susceptible to health problems.

We know that around 2,000 people age 55 and over die in state prisons each year and that upon release the formerly incarcerated are at greater risk of death due to cardiovascular disease and suicide compared to non-incarcerated individuals. Putting a population that is less likely to recidivate in conditions that contribute to these statistics is counterproductive at best. Going forward, it’s crucial that we think about how practices such as solitary confinement contribute to mortality statistics and poor health outcomes both within prisons and during the reentry process.

For the 95% of incarcerated people who will eventually return to communities across the nation, solitary confinement almost guarantees that they do so as less healthy individuals. This affects state and local resources beyond the costs of incarceration; the health costs of older adults are expected to rise substantially in the coming years, most of which will be paid for through taxpayer funded health programs. Viewed from a public health perspective, subjecting thousands of aging individuals to prolonged periods of immobility and isolation is dangerous and strains our medical infrastructure.

It’s time that state prison officials consider abolishing solitary, especially for older incarcerated people, similar to what lawmakers in New Jersey intended with S51 last year. The people we imprison aren’t lab rats (although treating animals this way is widely considered immoral), they are human beings who will be released back into society someday. Abandoning the practice of solitary is the next crucial step to chip away at the human and public health costs of mass incarceration.

Footnotes

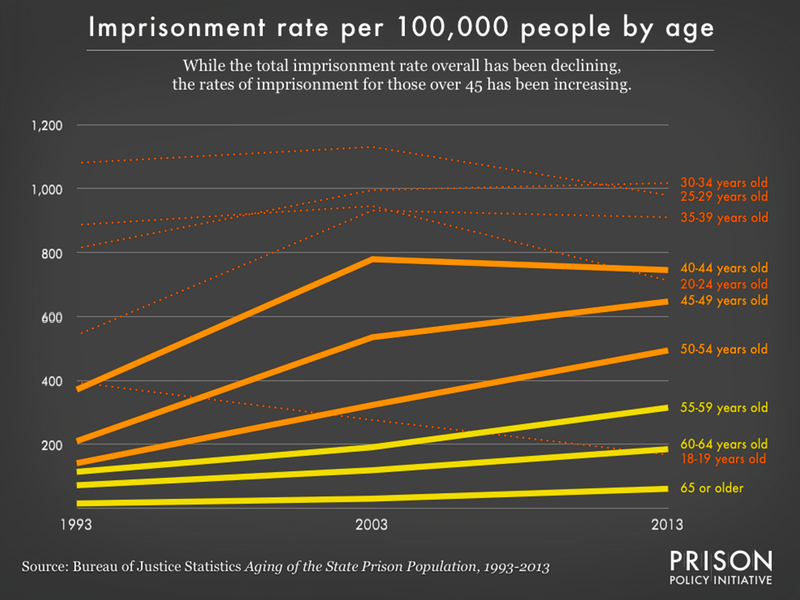

- Unfortunately, the available data required me to count people who are 45 and above as “older”, whereas the Yale/Liman study defined “older” adults as those people above 50. In order to calculate the estimate I used two Bureau of Justice Statistics reports (“Aging of the State Prison Population, 1993–2013” and “Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails, 2011–12”). According to the National Inmate Survey 2011-12, 13.1% of incarcerated people between 45-54 years old report spending time in restrictive housing at some point in the last 12 months or since admission to the facility, if shorter. For incarcerated people 55 and older that number is 8.9%. By multiplying these percentages with the total number of people in state prisons of equivalent ages in 2013 I was able to produce an estimate of 44,295 people in state prisons who experience some form of solitary each year. This number is a rough approximation, since multiple survey instruments are involved, but due to the lack of available systematic data, it provides us with a useful glimpse into the practice of solitary confinement for older adults. ↩

[…] following post comes from the always invaluable Prison Policy Initiative, which documents and publicizes how mass incarceration punishes our entire society, through […]