Prisons neglect pregnant women in their healthcare policies

Our 50-state survey finds that in spite of national standards, most states lack important policies on prenatal care and nutrition for pregnant women.

by Roxanne Daniel, December 5, 2019

This past August, released surveillance footage showed 26-year-old Diana Sanchez alerting Denver County Jail deputies and medical staff that she was in labor just hours before she gave birth to her son, alone in her cell. With her pleas ignored by staff, Sanchez was forced to give birth without any medical aid or assistance. Her experience is not isolated, as a number of reports by women in prisons and jails across the country have revealed a similar disregard for pregnant women’s basic needs.

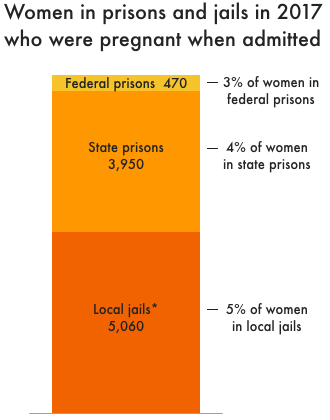

What’s more, the documentation of pregnancies and pregnancy care is sparse, sometimes anecdotal, and rarely generalizable on a national level. The most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) was collected more than 15 years ago. In 2002, BJS found that 5% of women in local jails were pregnant when admitted. For prisons, BJS reported that in 2004, 4% of women in state prisons and 3% of women in federal prisons were pregnant upon admission. The government has not released any further national data since.

These estimates are based on the number of women under local, state, and federal jurisdiction in 2017 and the percentages of women in prisons and jails who were pregnant when admitted, as reported by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. *Note that the estimate for women in local jails is based on the jail population on a single day, not the much greater number of women admitted to jail over the course of a year.

These estimates are based on the number of women under local, state, and federal jurisdiction in 2017 and the percentages of women in prisons and jails who were pregnant when admitted, as reported by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. *Note that the estimate for women in local jails is based on the jail population on a single day, not the much greater number of women admitted to jail over the course of a year.A recent study of 22 U.S. state prison systems and all U.S. federal prisons, published in the American Journal of Public Health, found a similar pregnancy rate; roughly 3.8% of the women in their sample were pregnant when they entered prison from 2016-2017. While the rate of pregnancy in prison may have remained stable since the early 2000s, the additional 10,000+ women imprisoned since then indicates that the number of women who are incarcerated while pregnant has grown, too. As long as the mass incarceration of women endures, incarcerated pregnancies will continue to rise.

Given the scale and stakes of this issue, it is imperative that correctional systems set policies that ensure the health and well-being of pregnant women in their custody. Provisions for adequate nutrition and prenatal medical care must be codified in policy to protect against negative health outcomes, such as miscarriages and low fetal birth weights, that can impact mothers and their children for the rest of their lives.

To see the extent to which these concerns are currently being addressed, we evaluated the policies of each state’s prison system and the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to screen for adherence to nationally recognized guidelines. Troublingly, many states fail to meet even basic standards.

| State | Specifies medical examinations as part of prenatal care | Provides screening & treatment for high-risk pregnancies | Requires pre-existing arrangements for deliveries | Prohibits or limits use of restraints | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Y | N | Y | N | DOC Request for Proposal No. 2012-02, 5.13 (A) |

| Alaska | Y | Y | Y | N | DOC Policy 808.06, DOC Policy 807.10, DOC Policy 807.02 |

| Arizona | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Health Services Technical Manual, AZ Senate Bill 1184 |

| Arkansas | Y | N | N | N | BCCP Administrative Regulation 829 |

| California | Y | Y | Y | Y | CDCR § 3999.309, CA Penal Code 3410-3424 |

| Colorado | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Administrative Regulation 700-12, CO Statute 17-1-113.7 |

| Connecticut | Y | N | Y | Y | DOC Administrative Directive 8.1, CT Senate Bill 13 |

| Delaware | Y | Y | Y* | Y | DOC Policy F-05, DOC Policy I-01.2 |

| D.C. | Y | Y | Y* | Y | DOC Program Manual, No. 6000.1I, DOC Policy 4910.1 |

| Florida | Y | Y | Y | Y | FL Statute 951.175, FL Health Services Bulletin 15.03.39, FL Senate Bill 524 |

| Georgia | N | N | N | Y | GA House Bill 345 |

| Hawaii | Y | Y | Y | Y | DPS Policy COR.10.1G.09, HI Statute 353.122 |

| Idaho | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Standard Operating Procedure 401.06.03.058 |

| Illinois | N | N | N | Y | IL § 5/3-15003.6 |

| Indiana | Y | N | Y | N | IN § 11-10-3-3 |

| Iowa | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC HSP-621, DOC HSP-615, HSP-720 |

| Kansas | Y | Y | N | N | DOC Policy 10-122D |

| Kentucky | N | N | N | Y | KY SB 133 |

| Louisiana | N | N | N | Y | LA SB 256 |

| Maine | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Policy 18.23 & 13.23, DOC Policy 18.19.1 & 13.19.1 |

| Maryland | Y | Y | Y | Y | MD § 12.02.09.02, DPSCS Policy 705 |

| Massachusetts | Y | Y | N | Y | DOC Policy 620.05 |

| Michigan | Y | N | N | N | DOC Policy 03.04.100 |

| Minnesota | Y | Y | N | N | DOC Instruction 500.010SHK |

| Mississippi | Policy unavailable | Policy unavailable | Policy unavailable | Policy unavailable | |

| Missouri | Policy unavailable | Policy unavailable | Policy unavailable | Y | MO SB 870 |

| Montana | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Policy 4.5.5 which directs facilities to follow the NCCHC Standards for Counseling and Care of the Pregnant Inmate |

| Nebraska | Y | Y | N | Y | DOC Policy 115.04 |

| Nevada | Y | N | Y | Y | DOC Administrative Regulation 623 |

| New Hampshire | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Policy 6.19 |

| New Jersey | Y | N | Y | Y | NJ Title 10A:16-6, NJ § 10A:31-13.10 |

| New Mexico | Y | Y | N | Y | Policy DC-170100, NM § 33-1-4.2 |

| New York | Y | N | Y | Y | NY CRR 7651.17, NY COR § 611 |

| North Carolina | Y | Y | Y* | Y* | DPS Policy CC-4, DPS Policy TX I-9 |

| North Dakota | N | N | N | Y | ND Correctional Facility Rules Standard 43 |

| Ohio | Y | Y | N | Y | DRC Policy 68-MED-23 |

| Oklahoma | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Policy OP-140145 |

| Oregon | Y* | Y* | Policy unavailable | Y | DOC Policy 40.1.1 |

| Pennsylvania | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Policy 13.02.01, PA SB 1074 |

| Rhode Island | N | N | N | Y | 240-RICR-30-00-1 |

| South Carolina | N | N | N | N | |

| South Dakota | Y | N | N | N | DOC Policy 1.4.E.2 |

| Tennessee | N | N | N | N | |

| Texas | Y | N | N | Y | TDCJ Policy G-55.1, TX § 501.001 |

| Utah | N | N | N | Y | UT § 64-13-46 |

| Vermont | N | N | N | Y | VT § 801a |

| Virginia | Y | Y | N | Y | DOC Operating Procedure 720.1, 6 VAC 15-40-985 |

| Washington | Y | Y | N | Y | DOC Policy 610.650, RCW 72.09.651 |

| West Virginia | N | N | N | N | |

| Wisconsin | N | N | N | N | |

| Wyoming | Y | Y | Y | Y | DOC Policy 4.317 |

| Federal | Y | N | Y | Y | 28 CFR § 551.22, First Step Act |

Most states lack important policies on prenatal care

All U.S. prisons and jails are required to provide prenatal care under the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, but no detailed federal standards have been set to ensure that women are actually receiving the care they need.

The National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) has published a set of standards for the treatment of pregnant women in prison, such as appropriate medical examinations as a component of prenatal care, specialized treatment for pregnant women with substance use disorders, and limited use of restraints throughout the course of the pregnancy. (A handy summary of the NCCHC’s standards is available from the Nursing for Women’s Health Journal, and the NCCHC’s full position statement provides additional context.)

Often, though, states fail to make their Department of Corrections policies publicly available, or even write guidelines on the care of incarcerated pregnant women in the first place. Despite the work of advocacy groups like the Rebecca Project for Human Rights and the ACLU, who have previously attempted to track available policies state-to-state, significant information gaps remain. Informed by this prior work, we tracked which states currently provide written policy on bare-minimum health standards for incarcerated pregnant women.

The data show that the lack of codified protocols for the care of pregnant women in state prisons is a widespread issue, and even policies that do exist frequently do not include adequate provisions for basic medical needs.

- Although a majority of state prison systems require some form of medically provided prenatal care, 12 states failed to provide any policy on this vital component of a healthy pregnancy. This helps to explain why the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in the 2004 survey, found that only half (54%) of pregnant women in prison reported receiving some form of prenatal care while incarcerated.

- Incarcerated pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to pregnancy complications related to substance use disorders, poor nutrition, and sexually-transmitted infections because they often come from precarious social and economic environments that exacerbate these risk factors. Their pregnancies are often designated as “high risk,” requiring special treatment to ensure their children are born in good health. We found that the federal BOP and 22 states have not provided any guidelines for specialized care for “high risk” pregnancies.

- Reports of women who have been forced to give birth in improper conditions, like Diana Sanchez, are far too common. In addition to reducing uncertainty and anxiety, hospital births provide a clean environment and adequate care in the event of complications. Illuminating the shortcomings of health care for pregnant women in prison, 24 states fail to codify any pre-existing arrangements for deliveries.

- The use of restraints (often referred to as shackling) has serious health impacts on pregnant women. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, shackling exacerbates pain, inhibits diagnosis of complications, and limits movement during the birthing process. Despite national standards condemning the practice, 12 states still provide no policy limiting restraints on women during pregnancy.

Incarcerated pregnant women require highly specific care in order to protect against adverse pregnancy outcomes. According to recent data from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, in some states, over 20% of prison pregnancies resulted in miscarriages; in others, preterm birth rates exceeded the national average (about 10%). The variability of these outcomes speaks to the inconsistent medical care afforded women in prisons across the country, and suggests that more universal policy standards could make pregnancy outcomes more equitable.

Critical pregnancy nutrition standards are also missing from policy

In an April 2019 tour of the Arizona State Prison Complex at Perryville, the Prison Law Office found that pregnant or recently pregnant women universally reported receiving inadequate nutrition during their pregnancies. Here, diets were reported to be largely lacking in fruit and vegetables, and the only additional food pregnant women received was an extra peanut butter sandwich and a carton of milk per day.

National guidelines clearly state that adequate nutrition is essential for a healthy pregnancy. Furthermore, the American Public Health Association cites unbalanced, inadequate diets as risk factors for preterm birth, birth defects, and other developmental problems in early childhood.

In our analysis, we found that 31 states lack any policy on nutrition for incarcerated pregnant women (see the Appendix). However, even the prison systems with policies mentioning nutrition provide too much room for substandard enforcement. For example, in 12 states, no guidelines exist beyond vague phrasing such as “adequate” or “appropriate” nutrition. This allows for a wide range of abuses and deficiencies, like the lack of nutritious options reported in the Arizona State Prison Complex at Perryville.

California is a notable exception, providing an important policy model that includes specific requirements for supplemental nutrition for incarcerated pregnant women. By provisioning “two extra eight ounce cartons of milk or a calcium supplement if lactose intolerant, two extra servings of fresh fruit, and two extra servings of fresh vegetables daily” with extra allowance for “additional nutrients” ordered by a physician, the nutritional supplement pregnant women need is explicitly detailed. Unfortunately, California was the only state found to have provided a meaningful nutrient breakdown of additional food allowances for pregnant women.

Improving prison policies is just the first step

Even when it exists, state policy is not always adhered to. In the Prison Law Office’s tour of the prison in Perryville, women reported being shackled during transport to the hospital as well as in-cell deliveries as a result of inadequate monitoring. Arizona policy requires prisons to make arrangements for deliveries in advance and prohibits shackling during transport in their state policy, but the stories of these women reveal a critical implementation gap.

Further, our analysis focuses on policy affecting state and federal prison systems, excluding county-operated jails. Policy for local jails is even more variable, inaccessible, and incomplete, which makes it difficult to assess the care of pregnant women in jail custody. Policy gaps likely also make it harder for jail staff to provide adequate care for pregnant women. Given the higher pregnancy rate among women admitted to jails and the large share of women held in jails, egregious failures like Diana Sanchez’s experience are likely far too common.

Given enforcement gaps and the shortage of available jail data, it is clear that equitable standards of care for pregnant women are urgently needed to protect the health of incarcerated women and their children. Of course, policy is just a stepping stone to adequate conditions. Beyond explicit standards of care, comprehensive data collection and insights from incarcerated pregnant women are key to evaluating the true impact of locking up this especially vulnerable population.

The long-term effects of inadequate health care are an insidious collateral consequence of incarceration. When the future health and well-being of mothers and their children are at stake, comprehensive policy and reform is past due.

| State | Policy on nutrition for pregnant women | Policy language or specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | AZ DOC Diet Reference Manual (June 2018) | Recommends an additional 300 kcal per day and an additional 10g of protein (for a total of at least 60g per day). The manual states that, “This diet provides an adequate quantity of most nutrients as prescribed by the RDA Standards of the National Academy of Science – National Research Council.” Prenatal vitamins are also recommended. |

| California | 15 CCR § 3050, 15 CA ADC § 3050 | “Pregnant inmates shall receive two extra eight ounce cartons of milk or a calcium supplement if lactose intolerant, two extra servings of fresh fruit, and two extra servings of fresh vegetables daily. A physician may order additional nutrients as necessary.” |

| Colorado | CO DOC AR 700-12 | No specifications; simply states “Pregnancy management is specific as it relates to the following: … Appropriate nutrition” |

| Delaware | Del. DOC Policy D-05 | “No specifications; simply lists “Pregnancy” as one of many “types of therapeutic diets” |

| D.C. | DC DOC Policy 2120.3E | Only specifies “snacks for diabetics and pregnant female inmates” |

| Kentucky | KRS 441.055 | DOC minimum standards applying to jails “shall include requirements for adequate nutrition for pregnant prisoners” |

| Maine | ME DOC Policy 18.23 (AF) & 13.23 (JF) | “Pregnancy services shall include… nutritional guidance and counseling….” and, postpartum, “The prisoner or resident shall be provided with additional food and/or nutritional supplements, when indicated and ordered by the facility health care provider, while breast pumping.” |

| Massachusetts | MA DOC Health Services Division Policy 103 DOC 620 | No specifications; simply mandates that written procedures exist “to ensure regular prenatal care is received, including… nutrition guidance” |

| Minnesota | Minn. DOC Instruction 500.010SHK | “The intake nurse must… write medical authorizations for a pregnancy snack bag” |

| Montana | MT DOC Policy 4.5.5 | Follows NCCHC Standards for Health Services in Prisons 2018, which recommend prenatal vitamins, diets that “reflect national guidelines,” and that “when possible, additional food in between meal times should be provided as physiologic changes and nausea may create a need for more frequent meals.” These standards also call for “appropriate nutrition” and prenatal vitamins for lactating women. |

| Nebraska | NE DOCS AR 115.04 | No specifications; simply states, “Pregnancy management shall include… appropriate nutrition” |

| New Hampshire | NH DOC PPD 6.19 | No specifications; simply states, “Offenders… will receive regular pre-natal care, to include… nutrition guidance” |

| New Jersey | NJ Admin. Code § 10A:16-6.1 | “The Department of Corrections shall provide a pregnant inmate with medical and social services, which shall include: … Nutritional supplements and diet as prescribed by the physician” |

| New Mexico | NM Policy CD-170100 | No specifications; simply states, “Provisions of pregnancy management include… Appropriate nutrition.” The attached Medical Diet Order Form includes a checkbox for “Pregnancy Diet” but no further details. |

| New York | NY CRR 7651.17 | No specifications; simply states, “The department shall provide comprehensive prenatal care… which shall include… nutritional guidance” |

| North Carolina | NC Dept. of Public Safety Prisons Policy CC-4 | No specifications; simply states, “Offenders… will receive regular pre-natal care, to include… nutrition guidance” |

| Oklahoma | OK DOC OP-140145 | No specifications; simply states, “Appropriate nutrition will be made available to all [pregnant] inmates.” |

| Pennsylvania | PA DOC Policy 13.2.1 | The Medical Department provides prenatal vitamins. The Parenting Program Director informs incarcerated pregnant people of prenatal classes available, including instruction in prenatal nutrition. “A prescription for therapeutic/pregnancy diet and snack shall be issued if deemed necessary by the Medical Department and/or the OB/GYN.” Attachment 13-A is mentioned in the policy but could not be located; it may provide further detail. |

| Texas | TDCJ Policy G-55.1 | Incarcerated pregnant people receive “diet counseling” and “vitamins”; no further specifications. |

| Washington | WA DOC Policy 610.650 | No specifications; simply lists “Appropriate nutrition” under “Pregnancy management” |

Peter, Pauline, cofounder of National CURE, thirty years ago was able to provide WIC coverage to pregnant prisoners. Are any prisons and jails still providing WIC access?

That’s a great question, and we unfortunately don’t know the answer – but good to know that WIC can be an option for people in prison who are pregnant.

Great work! We need policy that mandates reporting of pregnancy and outcomes occuring within incarceration settings. Advocacy and research is greatly needed regarding mother and child separation within 24-48 hours after delivery and subsequent permenancy outcomes. Postpartum care and information on parental rights during incarceration are also chief concerns for this population.