Since the 1980's crime has fallen, but the number of people in jails tripled. Our new report finds two troubling explanations for why this has occurred: the rise in pre-trial detention and the renting of jail space to other authorities.

May 31, 2017

Contact:

Joshua Aiken

jaiken [at] prisonpolicy.org

(413) 527-0845

Easthampton, Mass. — State capitols share responsibility for growing jail populations, charges a new report by the Prison Policy Initiative. “Jails are ostensibly locally controlled, but the people held there are generally accused of violating state law, and all too often, state policymakers ignore jails,” argues the new report, Era of Mass Expansion: Why State Officials Should Fight Jail Growth.

The fact that jails are smaller than state prison systems and under local control has allowed state officials to avoid addressing the problems arising from jail policies and practices. “Reducing the number of people jailed has obvious benefits for individuals, but also helps states curb prison growth down the line,” says Joshua Aiken, report author and Policy Fellow at the Prison Policy Initiative.

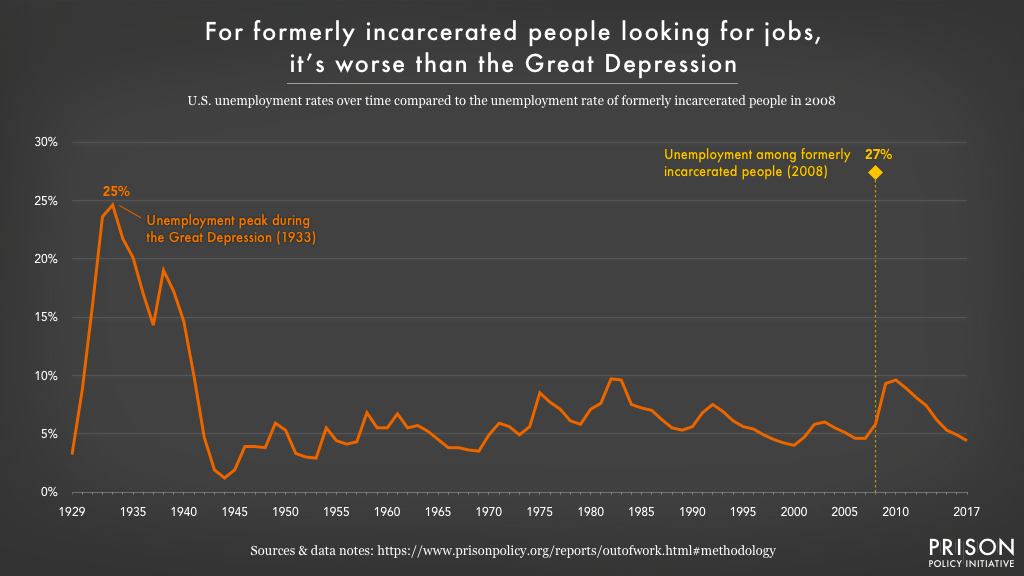

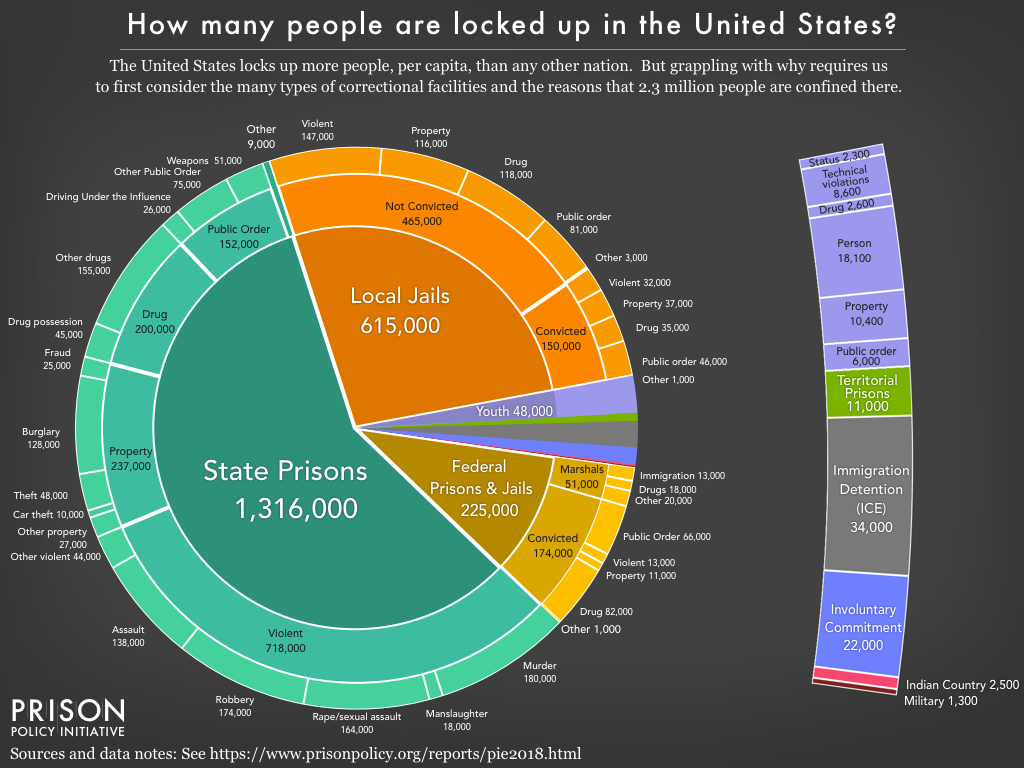

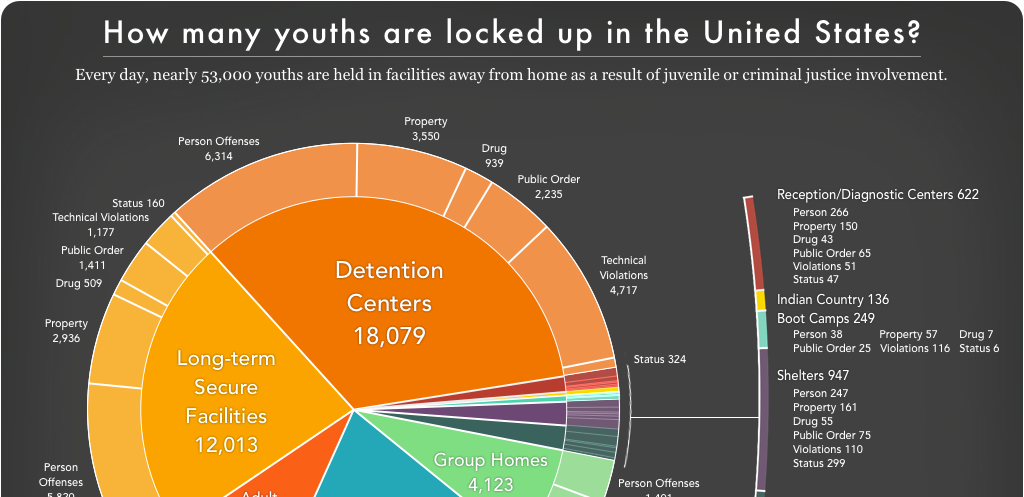

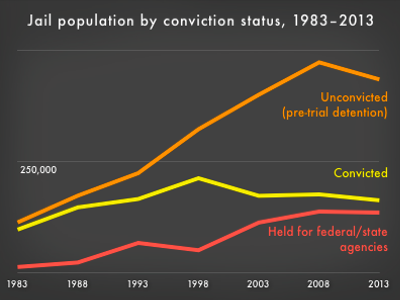

Every year, 11 million people churn through local jail systems, mostly for minor violations of state law. Of the 720,000 people in jails on a given day, most have not been convicted of a crime and have either just been arrested or are too poor to make bail. And since the 1980s, crime has fallen but the number of people jailed has more than tripled.

The new report finds that the key driver of jail growth is not what one might expect – courtroom judges finding more people guilty and sentencing them to jail. In fact, the number of people serving jail sentences has actually fallen over the last 20 years. Instead, the report finds two troubling explanations for jail growth:

- An increasing number of people held pre-trial.

- Growing demand from federal and state agencies to rent cell space from local jails.

Recognizing the importance of state-specific data for policymakers and advocates, the report offers more than a hundred graphs that make possible state comparisons of jail trends. The report uncovers unique state problems that drive mass incarceration:

- In some states, state officials have not utilized their ability to regulate the commercial bail industry, which has profited from the increased reliance on money bail and increased bail amounts. These trends have expanded the pre-trial population dramatically over time.

- In other states, state lawmakers have expanded criminal codes, enabled overzealous prosecutors, and allowed police practices to play a paramount role in driving up jail populations, while underfunding pre-trial programs and alternatives to incarceration.

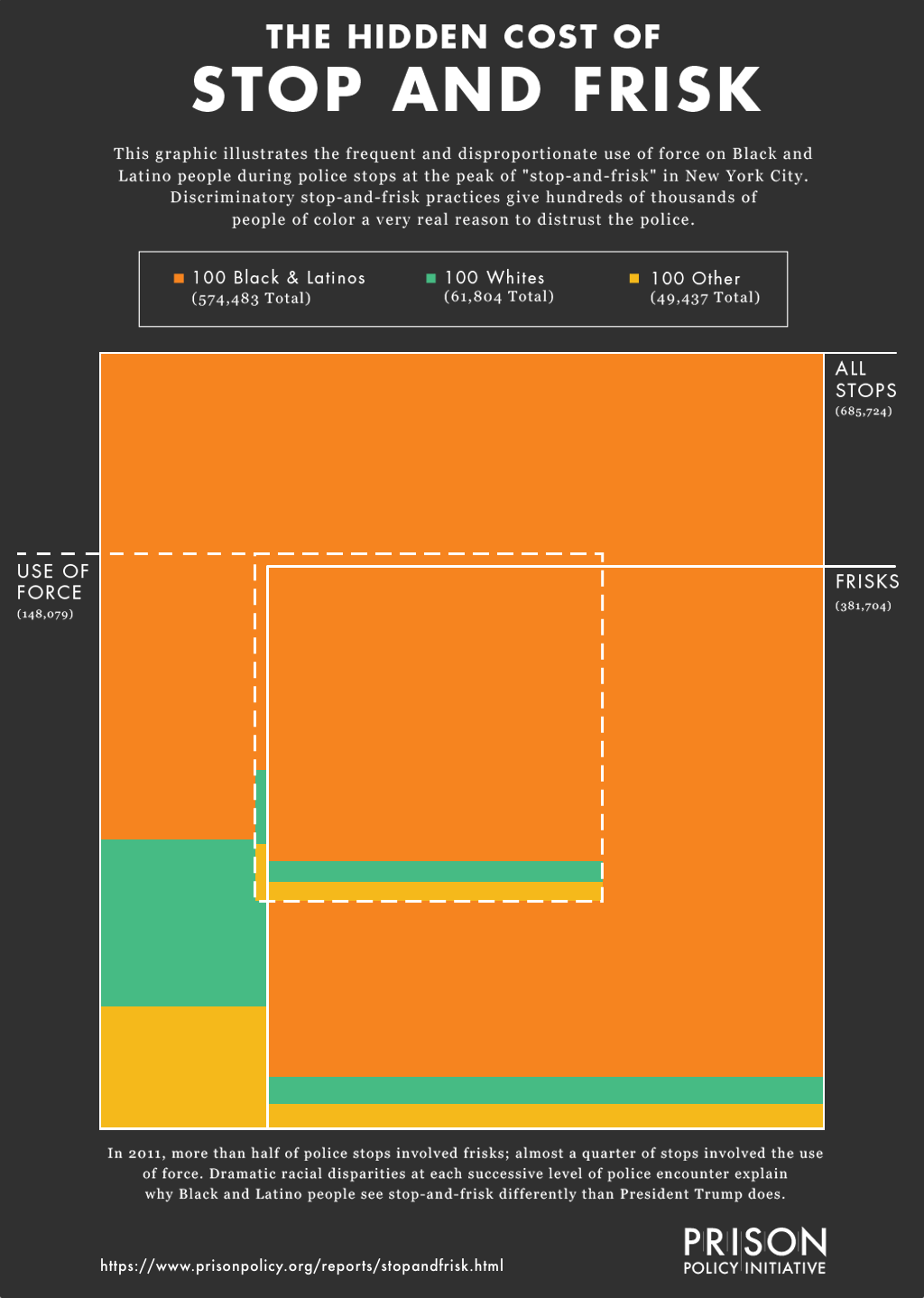

- In 25 states, 10% or more of the people confined in local jails are being held for state or federal agencies, with some counties even adding capacity to meet the demand. This report is the first to be able to address the local jail population separately from the troubling issue of renting jail space.

Era of Mass Expansion draws particular attention to the states where the dubious practice of renting jail space to other authorities contributes most to jail growth. “Local sheriffs, especially in states like Louisiana and Kentucky, end up running a side business of incarcerating people for the state prison system or immigration authorities,” explains Aiken. “Renting out jail space often creates a financial incentive to expand jail facilities and keep more people behind bars.” The report finds that renting jail space for profit has contributed more to national jail growth since the 1980s than people who are being held by local authorities and who have actually been convicted of crimes.

For state policymakers, the report offers 10 specific recommendations to change how offenses are classified and treated by law enforcement, eliminate policies that criminalize poverty or create financial incentives for unnecessarily punitive practices, and monitor the upstream effects of local discretion. “There are plenty of things local officials can do to lower the jail population,” says Aiken. “With this report, I wanted to bring in state-level actors by showing how much of the solution is in their hands.”

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization produces big-picture data publications like Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie to help people fully engage in criminal justice reform. Era of Mass Expansion builds upon the organization’s 2016 analysis of the cycle of poverty and jail incarceration, Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time.

The new report is available at www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/jailsovertime.html.