As more jails ban face-to-face visits in favor of paid video chats, a growing number of people in jail are being cut off from their families when the technology breaks down.

by Sarah Watson,

June 18, 2019

Jails are increasingly replacing in person visits with video calls. This high-tech fad goes against the recommendations of the American Correctional Association, the American Bar Association, and even the Department of Justice’s National Institute of Corrections. These jails ignore the many problems we’ve documented, such as high costs for families, poor quality of the systems and the loss of human contact. But there’s another liability that jails now have to consider: What happens when their shiny new technology fails?

Their vendors — who provide the systems for free in exchange for charging high rates to the families — will say that their technology is perfect. As every person who owns a computer knows, however, technology is not flawless, and these systems do fail — sometimes keeping people in jail from contacting their families for weeks at a time:

We surveyed recent news stories about video systems breaking in jails that had chosen to replace traditional in-person visits with the technology.

| County |

State |

Time Down |

Year |

Details |

Source |

| Shelby County Jail (Memphis) |

Tennessee |

2 weeks |

2019 |

The vendor (GTL) cut a fiber optic cable |

Source |

| Virginia Beach Correctional Center |

Virginia |

3 months |

2018 |

Jail typically averages 4,000 visits a month |

Source1 Source2 |

| Williams County Correctional Center |

North Dakota |

2 months |

2017 |

System updates originally brought the system down, then it was discovered the upgrade was incompatible with the old equipment |

Source |

| Milwaukee County Jail |

Wisconsin |

At least one month |

2013-2014 |

Visual went down leaving only audio |

Source |

| Boone County Jail |

Arkansas |

“months” |

2018 |

Either a lightning strike or a software glitch brought the system down, administrators were not sure which was the cause. |

Source |

| Volusia County Branch Jail |

Florida |

One month |

2017 |

Lightning struck an integral part of the visitation system. It took multiple technicians to conclude the entire system needed to be replaced. |

Source |

| Pontotoc County Justice Center |

Oklahoma |

Three weeks |

2017 |

Visitation went down due to a “computer issue.” |

Source |

| Madison County Detention Center (Huntsville) |

Alabama |

>2 weeks |

2017 |

Planned system updates meant visits were suspended. |

Source |

| Montgomery County Detention Facility |

Alabama |

About a week |

2018 |

“Technical Issues” disrupted visitation as the jail waited for a replacement machine. |

Source |

| Olmsted County Adult Detention Center (Rochester) |

Minnesota |

1 day |

2018 |

The visitation system crashed, leaving visitors unable to schedule a visit or see their loved ones. The sheriff also confirmed the system sometimes goes down due to weather conditions as well. |

Source |

| Ada County Jail |

Idaho |

|

2019 |

Ada County Jail experiences consistent technical issues. One visitor to Ada County Jail recalled, “It didn’t work half the time. You’d have to call to see if [the system] was down.” |

Source |

| Mecklenburg County Jail (Charlotte) |

North Carolina |

|

2017 |

Frequent problems and system outages caused prisoners to miss their visits. “The video chat would go in and out. Sometimes half the screen would be cut off, and sometimes they wouldn’t work at all,” a former prisoner remembered. “You wouldn’t even get your visitation; you would have to wait until the next week, because even though the system was down, they would not make up the visitation you missed.” |

Source |

The good news is that counties are starting to take notice of the downsides to video calling. Most recently, the sheriff of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (see table above) fulfilled a 2018 campaign promise to reinstate in-person visits, on the grounds that video should be used in addition to in person visits, not as a substitute.

“Allowing our residents to stay connected to family and loved ones through in-person visits improves public safety,” Sheriff McFadden explained. “This simple step alone has been shown to significantly lower the chances that a person will commit another crime after they get out. It also reduces the chance a person will commit an infraction inside the jail which could adversely impact their release. In addition, it improves mental health outcomes and strengthens family units and community ties.”

Mecklenburg County had the right idea. When this technology works, it should be considered a supplement to in-person visits, not a substitute; and when the technology fails, it’s useless. Instead of investing in flawed technology, jails should be looking for more ways to increase traditional methods of family contact.

The Democratic candidates are missing an opportunity to pitch sweeping criminal justice reform as an economic justice issue.

by Wanda Bertram,

June 12, 2019

Multiple Democratic presidential candidates have staked their campaigns on promises to fight for economic justice and protect low-income people from ruin. So it’s mysterious and frustrating that none of these candidates have proposed to end our justice system’s criminalization of poverty – at least beyond the occasional nod to ending money bail.

These candidates are missing an opportunity. The incomes of people in U.S. prisons and local jails are overwhelmingly low, and one in two American adults has had a close relative incarcerated, meaning that a candidate who understands the criminalization of poverty could propose transformative reforms and speak to a huge number of voters. In particular, candidates are missing an opportunity to speak to Black voters, who are hit hardest by policies that punish poor people.

To be sure, many Democratic candidates have alluded to economic inequality in connection with criminal justice reform — and Bernie Sanders even uses the phrase “criminalizing poverty” on his campaign website — but I’ve seen no indication that any of the candidates can speak to either the specifics or the scale of this problem. Candidates must go beyond criticizing money bail, and promise to end the unequal treatment of poor people at every stage of the justice process:

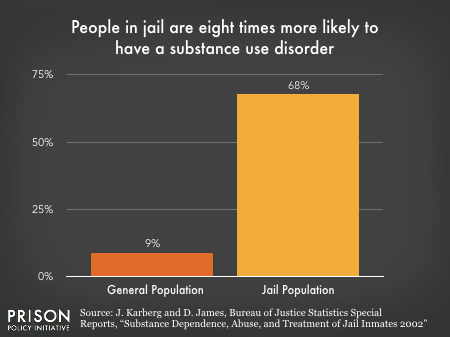

1. End poverty-related arrests and jail bookings. Far too many Americans who can’t afford housing, drug treatment or mental health services are instead arrested on minor charges related to their homelessness or illness. Many others end up in jail because they can’t afford burdensome fines and fees. An unfortunate downstream effect is jail overcrowding, which leads counties – largely in rural areas – to spend public money on harmful jail expansion rather than social welfare.

Presidential candidates should commit to helping state and local governments shift their priorities, making it easier to support low-income people and harder to jail them:

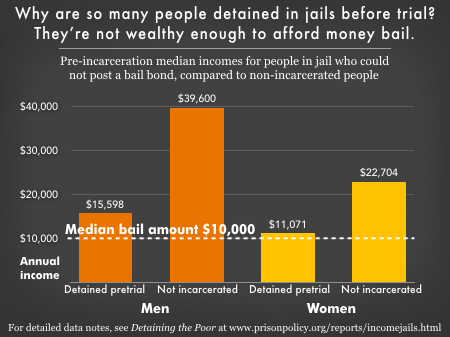

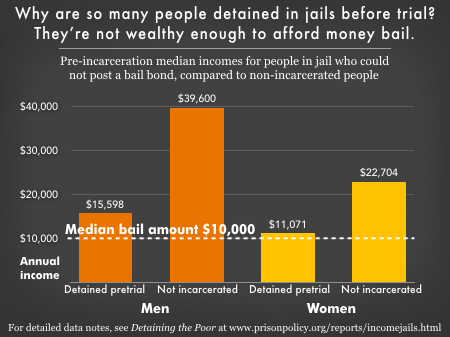

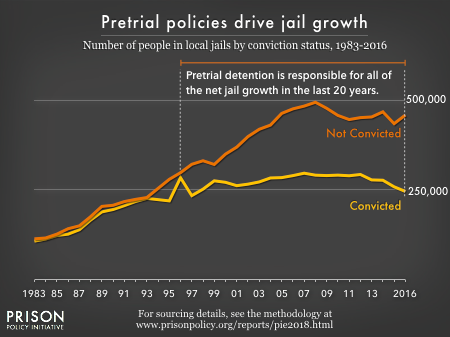

2. Guarantee poor people equal justice before trial. Two major injustices — pretrial detention and lack of access to counsel — ensure that low-income people are disproportionately convicted. Pretrial detention doesn’t just make defendants more likely to plead guilty; it also puts them at risk of losing their jobs and homes, and imposes huge costs on their families, before they’re ever convicted.

Candidates should promise to:

- Ensure that local public defender systems are fully funded, that they no longer charge co-pays to defendants, and that counsel is guaranteed at any hearing that could result in detention.

- Incentivize counties to drastically reduce pretrial detention by ending commercial money bail, and replacing it with release on recognizance, unsecured bonds, and other alternatives.

- Use the power of the Federal Communications Commission to regulate the cost of phone calls from jail, which can strain public defenders’ resources, not to mention those of family members.

- Subsidize county-level pretrial services to help low-income people make their court dates, such as text reminders and free childcare at court.

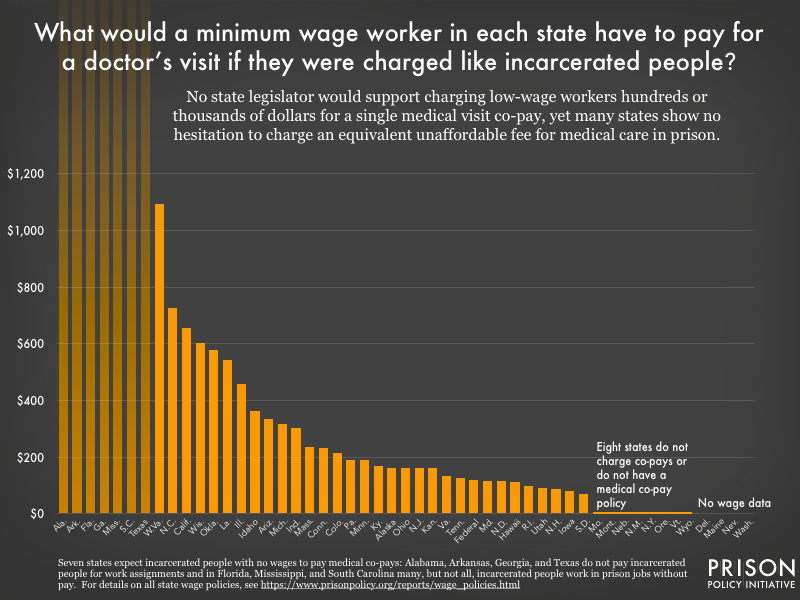

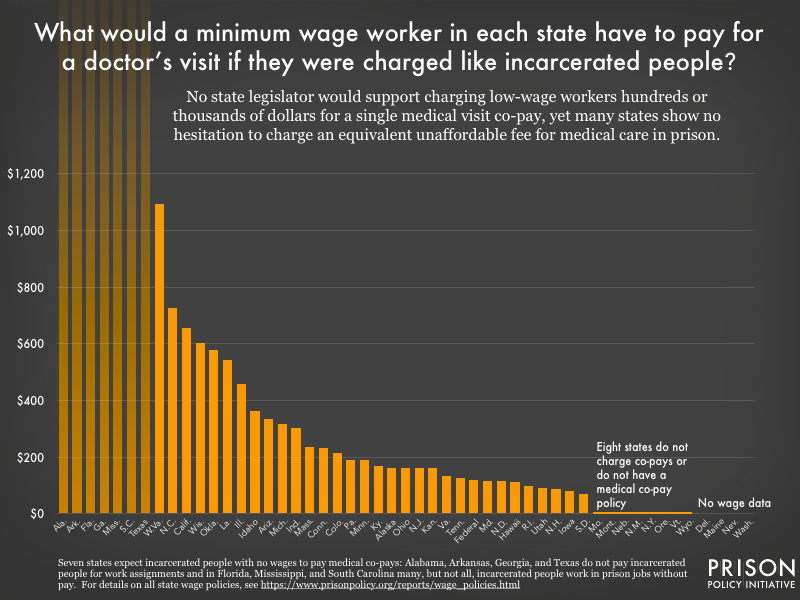

3. Stop forcing low-income families to subsidize the prison system. When someone goes to prison, their loved ones become their source of financial support. The financial pressure on these families grows when prisons fail to provide basic services, often driving families into debt. It shouldn’t be on relatives — disproportionately women — to pay for phone calls, medical care, nutritious food and educational resources for those behind bars, often when they’ve just lost a breadwinner.

Presidential candidates should commit to paying for incarcerated people’s needs to lift this burden on families:

4. Protect people from going back to prison just because they’re poor. Incarcerated people who come from under-resourced neighborhoods tend to return to those same neighborhoods after prison, now saddled with criminal records and far poorer than before.

Presidential candidates should avoid old narratives about how more surveillance, monitoring and job training are needed to “reduce recidivism” among people leaving prison. Instead, they should call the reentry process what it is: a period of extreme vulnerability that mostly affects impoverished people, and that can’t be improved without serious investments in formerly incarcerated people’s welfare. They should commit to:

- Identify the communities to which most formerly incarcerated people return, and subsidize additional low-income housing, drug treatment and mental health services in those communities.

- Help states create Departments of Reentry that connect people nearing release to permanent housing, medical care, and other resources.

- Incentivize states to pass laws expanding criminal record expungement, including automatic expungement for people convicted of minor offenses.

- End the harmful restrictions on association that prohibit formerly incarcerated people from helping each other rebuild their lives.

- Restore welfare benefits, including housing assistance, to people with criminal records.

- Urge states to abolish probation and parole fees, including fees for ankle monitors. End so-called “pay-only” probation schemes, which extract fees without providing any “services” at all.

- Incentivize states to “ban the box” on job applications, and to end restrictions on occupational licenses that lock people with criminal records out of good jobs.

- Expand federal tax benefits for businesses that hire people with criminal records.

- Incentivize states to end laws suspending driver’s licenses for non-driving offenses.

To be sure, there are many other policy changes that could help end the criminalization of poverty; this list is only a starting point. But it should be alarming that most of these policy options have gone unmentioned by any presidential candidate. Until the candidates commit to ending our criminal justice system’s abuse of poor people from arrest to release (and afterwards), their visions for economic justice won’t be complete.

A new government report reinforces harmful misconceptions about people convicted of sex offenses. Here's our take on how to parse the data.

by Wendy Sawyer,

June 6, 2019

By now, most people who pay any attention to criminal justice reform know better than to label people convicted of drug offenses “drug offenders,” a dehumanizing label that presumes that these individuals will be criminals for life. But we continue to label people “sex offenders” – implying that people convicted of sex offenses are somehow different.

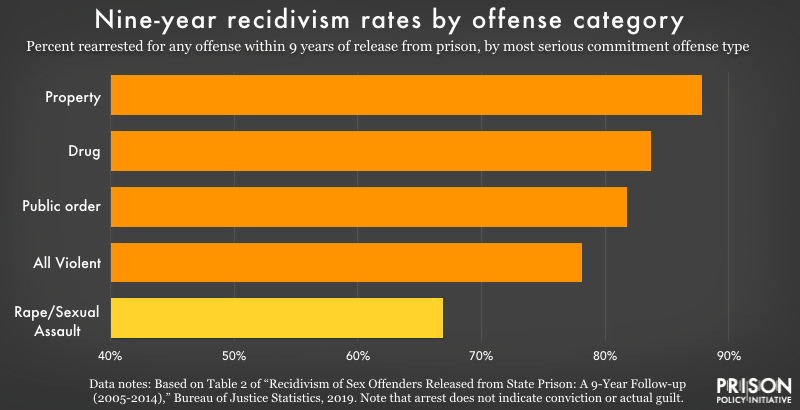

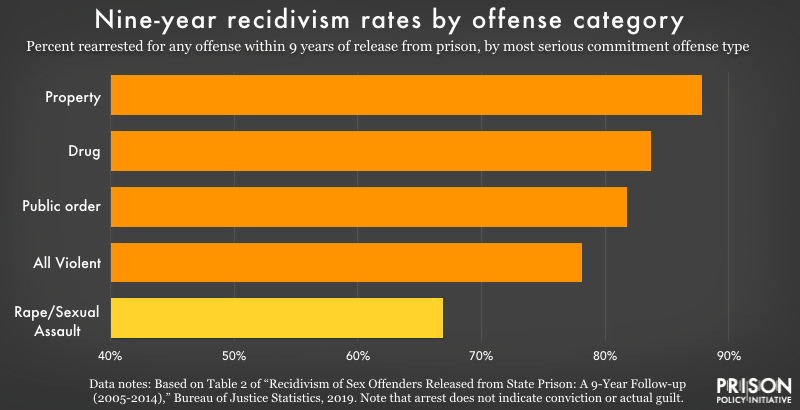

A new report released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics should put an end to this misconception: The report, Recidivism of Sex Offenders Released from State Prison: A 9-Year Follow-Up (2005-2014), shows that people convicted of sex offenses are actually much less likely than people convicted of other offenses to be rearrested or to go back to prison.

But you wouldn’t know this by looking at the report’s press release and certain parts of the report itself, which reinforce inaccurate and harmful depictions of people convicted of sex offenses as uniquely dangerous career criminals. The press release and report both emphasize what appears to be the central finding: “Released sex offenders were three times as likely as other released prisoners to be re-arrested for a sex offense.” That was the headline of the press release. The report itself re-states this finding three different ways, using similar mathematical comparisons, in a single paragraph.

What the report doesn’t say is that the same comparisons can be made for the other offense categories: People released from sentences for homicide were more than twice as likely to be rearrested for a homicide; those who served sentences for robbery were more than twice as likely to be rearrested for robbery; and those who served time for assault, property crimes, or drug offenses were also more likely (by 1.3-1.4 times) to be rearrested for similar offenses. And with the exception of homicide, those who served sentences for these other offense types were much more likely to be rearrested at all.

The new BJS report, unfortunately, is a good example of how our perception of sex offenses is distorted by alarmist framing, which in turn contributes to bad policy. That this publication was a priority for BJS at all is revealing: this is the only offense category out of all of the offenders included in the recidivism study to which BJS has devoted an entire 35-page report, even though this group makes up just 5% of the release cohort. This might make sense if it was published in an effort to dispel some myths about this population, but that’s not what’s happening here.

Framing aside, the recidivism data presented in the BJS report can offer helpful perspective on the risks posed by people after release. Whether measured as rearrest, reconviction, or return to prison, BJS found that people whose most serious commitment offense was rape or sexual assault were much less likely to reoffend after release than those who served time for other offense types. The BJS report shows that within 9 years after release:

- Less than 67% of those who served time for rape or sexual assault were rearrested for any offense, making rearrest 20% less likely for this group than all other offense categories combined (84%). Only those who served time for homicide had a lower rate of rearrest (60%).

- People who served sentences for sex offenses were much less likely to be rearrested for another sex offense (7.7%) than for a property (24%), drug (18.5%), or public order (59%) offense (a category which includes probation and parole violations).

- Only half of those who served sentences for rape or sexual assault had a new arrest that led to a conviction (for any offense), compared to 69% of everyone released in 2005 (in the 29 states with data).

While the data was more limited on returns to prison,1 the study found that within 5 years after release, people who had served sentences for rape or sexual assault also had a lower return-to-prison rate (40%) compared to the overall rate for all offense types combined (55%). BJS notes that some of these returns to prison were likely for parole or probation violations, but because of data limitations, it is impossible to say how many were for new offenses, much less how many were for rape or sexual assault.

In sum, the BJS data show that people who served time for sex offenses had markedly lower recidivism rates than almost any other group. Yet the data continue to be framed in misleading ways that make it harder to rethink the various harmful and ineffective punishments imposed on people convicted of sex offenses.

The recidivism data suggest that current legal responses to people convicted of sex offenses are less about managing risk than maximizing punishment. The desire for retribution is understandable; unquestionably, rape and sexual assault inflict serious and lasting trauma. But our criminal justice system does a poor job of providing survivors of rape, sexual assault, and other violent crimes what they really want. In a 2016 survey of crime survivors, the Alliance for Safety and Justice found that, “Survivors of violent crime — including victims of the most serious crimes such as rape or murder of a family member — widely support reducing incarceration to invest in prevention and rehabilitation and strongly believe that prison does more harm than good.” But more prison time is the default response: those released after serving sentences for rape and sexual assault served longer sentences, with a median sentence of 5 years (compared to 3 years for all others combined) and over a quarter serving 10 years or more before release.

And for many people convicted of sex offenses, confinement doesn’t end when their prison sentence does. Twenty states continue to impose indefinite periods of involuntary confinement under civil commitment laws – after individuals have completed a sentence (or, in some cases, before they are even convicted). Proponents justify the practice as “treatment,” but conditions of civil commitment are punitive and prison-like, and this confinement is hard to justify with the recidivism data we have. The likelihood of post-release arrest for another rape or sexual assault for this group is less than 2% in the first year out of prison, and after 9 years, less than 8% have been rearrested for a similar offense. Those who are released at age 40 or older are even less likely to be rearrested for another sex offense, with re-arrest rates about half those of people who are released at age 24 or younger.

After prison, a number of other special restrictions make reentry especially challenging for those who have served sentences for sex offenses, including registration, public notification, and restrictions to residence and employment. A current proposal suggests banning them from using New York City mass transit. (Even before release, some restrictions make it difficult for some people to leave prison when they would otherwise be paroled.) But these restrictions tend to cause more problems than they solve. Residence restrictions in particular have contributed to homelessness and other problems in cities where they leave little room for returning citizens. According to a 2015 U.S. Department of Justice brief, “residence restrictions may actually increase offender risk by undermining offender stability and the ability of the offender to obtain housing, work, and family support.”

In another recent academic article, Hanson et al. agree that these additional restrictions are “justified on the grounds of public protection,” even though the underlying assumptions may be wrong: “Individuals are targeted because policy-makers believe they are likely to do it again. This is a testable assumption, and, as it turns out, not entirely true.” Their analysis shows that individual recidivism risk varies widely, can be low enough to be indistinguishable from that of people convicted of non-sex offenses, and drops predictably over time. The data published by BJS track with those findings.

Collectively, the research seems fairly clear: our responses to people convicted of sex offenses do not reflect the actual – generally low – risks they present. Instead of panicking about the small portion who reoffend after release, it’s time we talk more rationally about responses that effectively support desistence from crime – and serve the actual needs of victims of violence.

Footnotes

We analyze gender and racial disparities in traffic and street stops, including arrests, searches, and use of force that occurs during stops.

by Prison Policy Initiative,

May 14, 2019

Jails have been described as the criminal justice system’s “front door,” but jail incarceration typically begins with the police, with an arrest. Before any bail hearing, pretrial detention, prosecution, or sentencing, there is contact with the police. But despite their crucial role in the process, we know less about these police encounters than other stages of the criminal justice system.

In particular, the experiences of women and girls1 – especially Black women and other women of color – are lost in the national conversation about police practices. They are also largely invisible in the the data. But as Andrea Ritchie details in Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color, women, too, are subject to racial profiling, use of excessive force, and any number of violations of their rights and dignity by police. In fact, women make up an increasing share of arrests and report much more use of force than they did twenty years ago. Yet while increasing recognition of women as a growing share of prison and jail populations has prompted facilities to adopt gender-responsive policies and practices, women’s rising share of arrests and other police contact has received less attention and policy response.

The current study

To shed more light on how women’s experiences at the front end of the criminal justice system differ from men’s experiences, we look at both arrest data and data about women’s other contacts with police. We first look at trends in arrest data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program. To complement this data, we also examine differences in other police encounters reported in the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) Contacts Between Police and the Public (CPP) reports, which are based on responses to the Police-Public Contact Survey (PPCS).

Critically, the UCR Program does not require police to report arrests by both sex and race/ethnicity, so that dataset offers no way to compare arrest trends of white, Black, and Latina women to each other or to their male counterparts. The PPCS partially fills that gap by including both sex and race/ethnicity of survey respondents; however, the BJS reports based on that survey do not engage this valuable intersectional data.2 The second section of this briefing includes our analysis of the most recent PPCS survey (conducted in 2015), to finally offer a view – from nationally representative data – of how women of different races and ethnicities experience police-initiated encounters differently than each other and men.

Part 1: Gender differences in interactions with police

Arrests: Women make up an increasingly large share of arrests

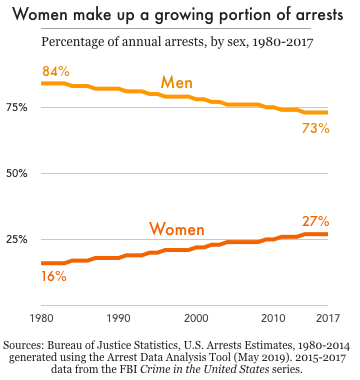

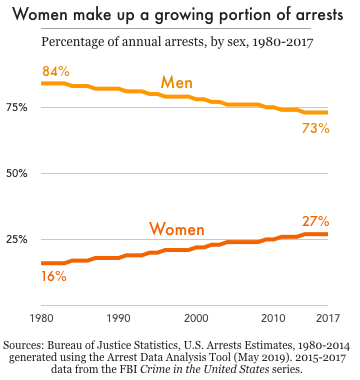

In the past two decades, the total number of arrests in the U.S. has dropped by more than 30 percent, from 15.3 million in 1997 to 10.6 million in 2017. However, this drop was mostly due to fewer arrests of men: the number of men arrested declined by 30.4 percent in that time, while the number of women arrested declined only 6.4 percent. As men’s arrest rates have fallen women’s arrest rates have remained fairly flat. As a result, women make up an increasingly large share of all arrests; as of 2017, women accounted for 27 percent of all arrests, up from 21 percent in 1997, and just 16 percent in 1980.3

In the past two decades, the total number of arrests in the U.S. has dropped by more than 30 percent, from 15.3 million in 1997 to 10.6 million in 2017. However, this drop was mostly due to fewer arrests of men: the number of men arrested declined by 30.4 percent in that time, while the number of women arrested declined only 6.4 percent. As men’s arrest rates have fallen women’s arrest rates have remained fairly flat. As a result, women make up an increasingly large share of all arrests; as of 2017, women accounted for 27 percent of all arrests, up from 21 percent in 1997, and just 16 percent in 1980.3

An increase in arrests of women for drug offenses helps explain why women’s arrest rates have remained steady, even as crime rates have hit historic lows and men’s arrest rates have plummeted. Of the more than 2 million arrests of women in 2017, 13.9 percent were for drug abuse violations – second only to property crimes (15.8 percent), and far more frequent than arrests for violent crimes (3.8 percent). Over the past five years – while the country has been in the throes of the opioid epidemic – drug arrests have increased 6 percent among men, but almost 25 percent among women.4

Table 1. Total UCR arrests declined more dramatically among men than among women between 2013 and 2017, due in part to a much greater increase in arrests of women for drug violations. Source: Crime in the United States 2017 Table 35

|

Percent change over 5 years (2013-2017) |

|

Male |

Female |

| All arrests |

-8.7% |

-6.4% |

| Index violent crimes |

+1.8% |

+4.4% |

| Index property crimes |

-18.8% |

-24.9% |

| Drug abuse violations |

+6.1% |

+24.7% |

Other police-initiated contact: Women interact with police more than arrest statistics suggest

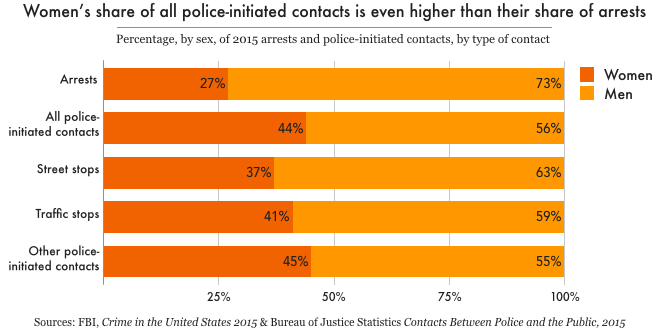

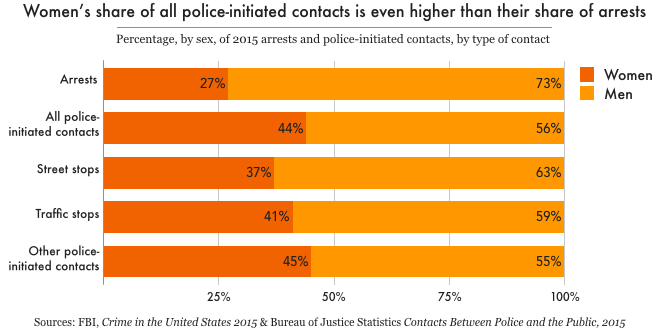

A key finding from the Contacts Between Police and the Public series is the true scale of women’s interactions with police, which is far greater than arrest numbers alone suggest. While arrests are sometimes used as a measure of the “first stage” of involvement with the criminal justice system, many encounters between the public and police do not result in arrest. This is especially true for women, who account for a much greater share of public-police interactions than they do actual arrests.

In 2015, there were about 2.1 million arrests – but about 12 million police-initiated contacts5 – with women ages 16 and over.6 That means that for every woman arrested, five more women were approached by police, either in a traffic stop, street stop, or in the execution of an arrest warrant. All police-initiated contacts are non-voluntary encounters, which are more likely than resident-initiated contacts (e.g. calling the police for help) to lead to arrest, further justice involvement, and other negative outcomes. The 2015 survey shows that women made up almost half (44 percent) of all police-initiated contacts, 41 percent of traffic stops (in which they were the drivers), and 36 percent of street stops, compared with 27 percent of all arrests. This is a critical point when assessing the need for gender-responsive policing policies and practices: basing an analysis solely on arrests would grossly underestimate the non-voluntary interactions women have with police.7

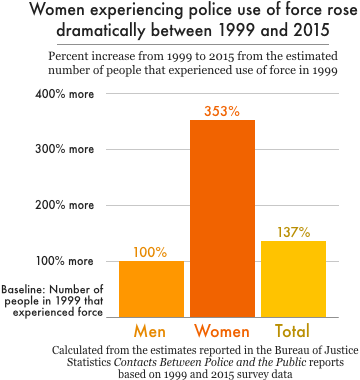

Use of force: Nearly doubled for men since 1999, but more than quadrupled among women

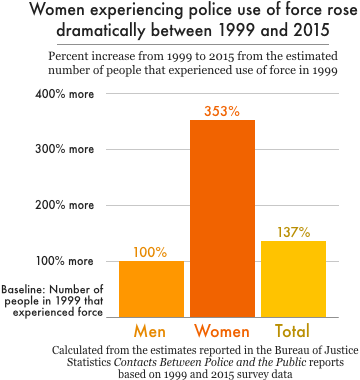

As with women’s share of arrests, women’s share of police encounters that involve the use or threat of force has increased significantly since 1999.8 That year, women made up just 13 percent of the approximately 422,000 people who experienced use of force during a police encounter. This percentage almost doubled by 2015, when women accounted for 25 percent of all people who experienced police use of force. Moreover, the total number of people experiencing police use of force more than doubled in that time, to 985,300 in 2015. But the increase in use of force was especially dramatic among women: the number of women experiencing police use of force in 2015 was 4.5 times (353%) the number experiencing force in 1999, up from 55,181 to 250,200. Meanwhile, the number of men experiencing police use of force doubled from 366,533 in 1999 to 735,100 in 2015.

As with women’s share of arrests, women’s share of police encounters that involve the use or threat of force has increased significantly since 1999.8 That year, women made up just 13 percent of the approximately 422,000 people who experienced use of force during a police encounter. This percentage almost doubled by 2015, when women accounted for 25 percent of all people who experienced police use of force. Moreover, the total number of people experiencing police use of force more than doubled in that time, to 985,300 in 2015. But the increase in use of force was especially dramatic among women: the number of women experiencing police use of force in 2015 was 4.5 times (353%) the number experiencing force in 1999, up from 55,181 to 250,200. Meanwhile, the number of men experiencing police use of force doubled from 366,533 in 1999 to 735,100 in 2015.

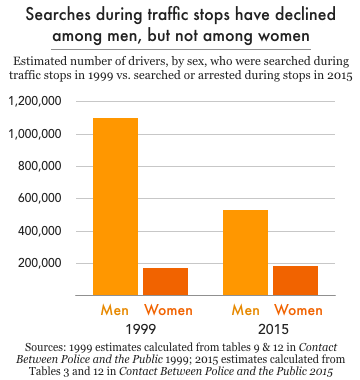

Traffic stops: Stops declined more for men, and women make up a larger share of those searched during stops

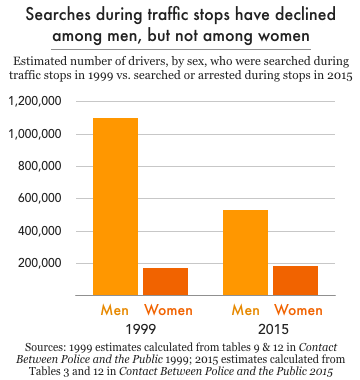

The 2015 survey shows another noteworthy shift in the numbers of men and women stopped by police while driving. While the percentages of both men and women experiencing traffic stops declined since 1999, women saw a smaller decline in stops than men did. In 2015, 10 percent of male drivers were stopped (down from 12.5 percent in 1999) compared with 7 percent of female drivers (down from 8.2 percent). These changes may sound small as percentages, but the decline in the rate among women actually masks a 378,000 increase in total number of traffic stops of women since 1999, while men were stopped 451,000 fewer times than in 1999.9

Women also make up a larger percentage of all people searched during traffic stops. In 1999, men who were stopped while driving were about four times as likely to be searched during the stop than women; by 2015, men were just twice as likely to be searched. The narrowing of this gap reflects a decline in searches of men; for women, the share of stops that resulted in search remained the same, at 2.3 percent. In 1999, police searched the driver or vehicle in 9.4 percent of stops of men, which amounts to over one million stops involving a search. In 2015, however, the percentage of stops involving male drivers that resulted in search or arrest dropped by half, to 4.7 percent – or over 500,000 stops. Female drivers, however, saw no change in their likelihood of search or arrest during a traffic stop.

Women also make up a larger percentage of all people searched during traffic stops. In 1999, men who were stopped while driving were about four times as likely to be searched during the stop than women; by 2015, men were just twice as likely to be searched. The narrowing of this gap reflects a decline in searches of men; for women, the share of stops that resulted in search remained the same, at 2.3 percent. In 1999, police searched the driver or vehicle in 9.4 percent of stops of men, which amounts to over one million stops involving a search. In 2015, however, the percentage of stops involving male drivers that resulted in search or arrest dropped by half, to 4.7 percent – or over 500,000 stops. Female drivers, however, saw no change in their likelihood of search or arrest during a traffic stop.

Part 2: Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in Police Stops

Data from the Police-Public Contact Survey (PPCS) allow us to take a more intersectional view of women’s contact with police, going beyond gender differences to include racial and ethnic differences among men and women, too. Again, this is the only national data we are aware of that enables any intersectional analysis of civilian experiences with police, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) does not attempt this analysis in its report on the survey’s results. That arrest data indicate racial disparities is well documented, but little is known – outside of individual stories – about how Black, Latinx, and white women experience police contact differently from each other and from their male counterparts.

Our analysis examines how race and gender, together, affect police-initiated stops, including arrests and use of force that occur during stops. It’s worth noting that police stops and arrests during these stops are relatively infrequent events, and that our findings are based on survey data from over 90,000 respondents, not the total U.S. population. That said, we find that the race, ethnicity, and gender affect policing outcomes differently depending on the context:

- Both race and gender affect the likelihood of a traffic stop.

- Race seems to matter more for men when it comes to street stops and more for women when it comes to arrests during a stop.

- Racial disparities are most apparent in use of force during a police-initiated stop, with Black and Latino men experiencing use of force more often than other groups, and Black women reporting similar use of force rates to white men.

Traffic stops: Black women are more likely than white or Latina women to be stopped

Both race and gender affect a person’s chances of being stopped by police while driving (excluding accidents or when they were passengers). Most broadly, the PPCS data shows that women were less likely than men to be stopped, and Black drivers were more likely to be stopped than white and Latinx drivers.10 More specifically, Black women were about 17 percent more likely to be in a police-initiated traffic stop than white women, and 34 percent more likely to be stopped than Latina women. Among men, Black drivers were about 12 percent more likely than white drivers – and 17 percent more likely than Latino drivers – to be stopped.

Table 2. See the Appendix for tables that show the statistical significance of differences between Black and Latina women compared to white women and all groups compared to white men.

| Women |

White |

7.1% |

|

Black |

8.3% |

|

Latina |

5.5% |

| Men |

White |

9.9% |

|

Black |

11.1% |

|

Latino |

9.2% |

These estimates are not adjusted for driving behavior, however, and given reported differences in driving patterns between demographic groups, it is likely that traffic stops of Black and Latina women per mile driven could be even higher compared to other groups than the survey data suggest.11

Street stops: Significant racial disparities among men, but not women

In contrast to traffic stops, the survey data on police-initiated street stops only showed significant racial disparities among men – not among women. Less than one percent of white, Black, and Latina women surveyed experienced a police-initiated street stop in 2015. However, the percentage of Black men who experienced a street stop (2.2 percent) was double that of white men (1 percent). A slightly greater portion of Latino men (1.2 percent) reported experiencing a street stop than white men, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 3. See the Appendix for tables that show the statistical significance of differences between Black and Latina women compared to white women and all groups compared to white men.

| Women |

White |

0.7% |

|

Black |

0.7% |

|

Latina |

0.5% |

| Men |

White |

1.0% |

|

Black |

2.2% |

|

Latino |

1.2% |

Arrests during stops: Significant racial disparities among women, but not men

Police-initiated traffic and street stops sometimes result in arrest, and the survey data show that Black women were at least as likely as white men to be arrested during a stop. White women, meanwhile, were about half as likely as white men to be arrested during a stop. Black women were arrested in 4.4 percent of police-initiated stops, which was roughly three times as often as white women (1.5 percent), and twice as often as Latinas (2.2 percent).

Among men, racial disparities in arrest-during-stop rates appear to be more related to the frequency of being stopped than the likelihood of being arrested if stopped. For women, on the other hand, racial disparities seem to be more related to what happens during the stop than whether they are stopped at all.

Table 4. See the Appendix for tables that show the statistical significance of differences between Black and Latina women compared to white women and all groups compared to white men.

| Women |

White |

1.5% |

|

Black |

4.4% |

|

Latina |

2.2% |

| Men |

White |

2.7% |

|

Black |

3.5% |

|

Latino |

4.2% |

Use of force during stops: Rates of Black women similar to white men; Black and Latino men most likely to experience force

About one percent of people surveyed indicated that they had experienced force or threat of force12 during a police-initiated stop, but use of force rates were higher for Black women than white or Latina women,13 and were highest among Black and Latino men. Black women actually experienced use of force during a stop about the same rate as white men, while white women were significantly less likely to experience use of force than white men. The marked gender disparity in reported use of force that is included in the BJS report Contacts Between Police and the Public, 2015 (2.7 percent for men versus 0.9 percent for women) masks the reality that these percentages are averages of racial and ethnic groups that are experiencing force at markedly different rates.

Table 5. See the Appendix for tables that show the statistical significance of differences between Black and Latina women compared to white women and all groups compared to white men.

| Women |

White |

0.3% |

|

Black |

0.9% |

|

Latina |

0.32% |

| Men |

White |

0.8% |

|

Black |

3.6% |

|

Latino |

2.5% |

Conclusion

As women become a more visible presence in our criminal justice system, it becomes increasingly urgent that we understand their experiences within it, both to better meet their needs and to enhance our analysis of how justice works (and doesn’t work) in the U.S. The policing of women, especially women of color, has received less attention than the policing of men; it’s even received less attention than the incarceration of women. Similarly, while correctional facilities are increasingly adopting gender-responsive policies and programs, there have been virtually no concerted efforts to create or implement trauma-informed or gender-responsive policing practices.

This oversight has serious consequences. Rates of sexual and physical abuse are high among justice-involved women – estimates range from half to over 90 percent – and are much higher than reported for men. Almost a third (31 percent) of women in jail have a current serious mental illness, which is over twice the rate among men in jail (14.5 percent) and over six times the rate among women in the general population (4.9 percent). With 12 million women per year experiencing police-initiated contacts – many of which involve searches, use of force, and other traumatizing experiences – it is critical that law enforcement take seriously the need for more female police officers,14 protocols, and trainings that can improve police-public interactions and reduce the harms to women.

Finally, the invisibility of Black women and other women of color in the national discourse about policing – even in the wake of high-profile tragedies like the arrest and jail death of Sandra Bland – means that the full scope of racial discrimination in policing is unknown, and certainly understated. Making policing more transparent, accountable, effective, and just will mean bringing the experiences of these women to light.

Data sources and methodology

Arrest data come from the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program (reported annually in the Crime in the United States series). Other police contact data are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Police-Public Contact Survey (PPCS), most recently conducted in 2015 and published in 2018. The police contact data in Part 1 comes from the BJS reports based on the results of that survey, in the Contacts Between Police and the Public series. The analysis in Part 2 used the raw PPCS data, available from the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data (NACJD) here.

Using the PPCS data for the analysis in Part 2, respondents were coded into one of eight mutually exclusive sex-race categories: Black female, Black male, Latina (female), Latino (male), white female, white male, non-Hispanic other race female, and non-Hispanic other race male (the last two categories include multi-racial respondents, and results were not included in this report because of the small sample sizes and the disparate racial and ethnic categories they included.)

Our analysis focuses on non-voluntary, police-initiated stops. Therefore, the two types of police contacts included in the analysis were “stopped by police in public place (non-vehicle)” and “stopped by police while driving.” Types of police contacts excluded from the analysis were: “respondent in vehicle stopped by police” (i.e. not driving), “in traffic accident,” “other police stops or approaches,” “crime/non-crime emergencies,” and “seeking other help from police.”

“Arrests” in our analysis of the PPCS (in Part 2) refer to only those arrests that occurred during non-vehicle (street) stops, vehicle (traffic) stops, or either type of stop. Use of force refers to whether, during the encounter, the police officer did any of the following to the respondent: push, grab, kick, hit, spray with chemical or pepper spray, use an electroshock weapon (Taser), or point a gun at them.

We used Wald tests to determine whether there were statistically significant differences in average (mean) incidence of stops, arrests, and use of force between each sex-race category in comparison to two references categories: white women and white men. We used the weighting provided by the Bureau of Justice Statistics to approximate a nationally representative sample.

Acknowledgements: This briefing was a collaborative effort, but Wendy Sawyer served as the editor and created the graphics. We thank Public Welfare Foundation for their support of our research into the experiences of women who come into contact with the criminal justice system.

Footnotes

Appendix

Appendix Table 1 provides the data behind the graph titled “Women experiencing police use of force rose dramatically between 1999 and 2015.”

Use of force has increased overall, but most dramatically among women

Appendix Table 1.

|

1999 |

1999 |

2015 |

2015 |

1999 to 2015 |

|

Percentage of all people who experienced use of force during a police encounter |

Estimated number of people that experienced use of force during a police encounter |

Percentage of all people who experienced force during a police encounter |

Estimated number of people experienced use of force during a police encounter |

Percent increase in number of people experiencing police use of force |

| Men |

87% |

366,533 |

75% |

735,100 |

100% |

| Women |

13% |

55,181 |

25% |

250,200 |

353% |

| Total |

100% |

421,714 |

100% |

985,300 |

137% |

Expanded tables from Part 2

Reading these tables: There are two reference groups for looking at whether differences are statistically significant. First, we look at whether the differences in contact for Black and Latina women compared to white women are statistically significant. We then look at all sex-race groups compared to white men. The level of statistical significance is indicated for each difference, for example, “p<0.1%” indicates that a difference is statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. Where there isn’t a comparison made (for example, white women are not compared to themselves), the cell is marked with “–” and when there is no statistically significant difference between groups, this is indicated simply with “No.”

Percentage of drivers who experienced a vehicle stop in 2015

Appendix Table 2.

|

|

Percentage who experienced a vehicle stop |

Is difference from white women statistically significant? |

Is difference from white men statistically significant? |

| Women |

White |

7.1% |

— |

Yes (p<.01) |

|

Black |

8.3% |

Yes (p<.05) |

Yes (p<.01) |

|

Latina |

5.5% |

Yes (p<.01) |

Yes (p<.01) |

| Men |

White |

9.9% |

— |

— |

|

Black |

11.1% |

— |

Yes (p<.1) |

|

Latino |

9.2% |

— |

No |

Percentage who experienced a street stop in 2015

Appendix Table 3.

|

|

Percentage who experienced a street stop |

Is difference from white women statistically significant? |

Is difference from white men statistically significant? |

| Women |

White |

0.7% |

N/A |

Yes (p<.01) |

|

Black |

0.7% |

No |

Yes (p<.1) |

|

Latina |

0.5% |

No |

Yes (p<.01) |

| Men |

White |

1.0% |

— |

— |

|

Black |

2.2% |

— |

Yes (p<.01) |

|

Latino |

1.2% |

— |

No |

Percentage who were arrested during a stop in 2015

Appendix Table 4.

|

|

Percentage who were arrested during a stop |

Is difference from white women statistically significant? |

Is difference from white men statistically significant? |

| Women |

White |

1.5% |

— |

Yes (p<.01) |

|

Black |

4.4% |

Yes (p<.05) |

No |

|

Latina |

2.2% |

No |

No |

| Men |

White |

2.7% |

— |

— |

|

Black |

3.5% |

— |

No |

|

Latino |

4.2% |

— |

No |

Percentage who experienced force during a police-initiated stop in 2015

Appendix Table 5.

|

|

Percentage who experienced force during a stop |

Is difference from white women statistically significant? |

Is difference from white men statistically significant? |

| Women |

White |

0.3% |

— |

Yes (p<.05) |

|

Black |

0.9% |

No |

No |

|

Latina |

0.32% |

No |

No |

| Men |

White |

0.8% |

— |

— |

|

Black |

3.6% |

— |

Yes (p<.01) |

|

Latino |

2.5% |

— |

Yes (p<.05) |

All too often, proposals to expand local jails receive no pushback or critical attention. A new report helps counties think twice.

May 6, 2019

Easthampton, Mass. – A new Prison Policy Initiative report gives cities and counties a long-needed tool for fighting mass incarceration: a guide to preventing unnecessary jail expansion. The report, Does our county really need a bigger jail?, lays out 33 questions that local decision-makers should ask in evaluating proposals for new or bigger jails.

“It’s very common today for jails to be overcrowded, because the number of people in jails nationwide has tripled in the last 30 years,” said report author Alexi Jones. “But in too many counties, jail growth is rooted in known policy failures like an overreliance on money bail. Local policymakers owe it to their constituents to find out if there is a better fix to overcrowding than just building a new or bigger jail.”

The report’s 33 questions for policymakers include:

- On a typical day, how many people are confined in the existing jail who have not been convicted?

- How many people in the county are incarcerated because they cannot afford to pay fines and fees?

- What specialized “diversion” courts and treatment programs is the county using to divert people struggling with substance use and mental illness into more effective treatments than jail?

- Do official cost estimates for building new jail space include not only the cost of construction, but the cost of debt service on the loan, annual operation costs, and collateral costs such as adverse impacts on public health?

“Building new jail space typically costs tens of millions of dollars or more, even as other options that are both more cost-effective and more compassionate are ignored,” said Jones. “If policymakers can’t answer these questions about why more jail space is necessary, they should not be undertaking jail expansion.”

For all 33 questions, the report also offers a set of alternatives and best practices, including:

- Releasing more pretrial defendants on their own recognizance, and investing in pretrial services to help them make their court dates;

- Requiring judges to set fines and fees based on a defendant’s ability to pay;

- Investing in specialized “problem-solving” courts for people with mental health or substance use disorders that serve as true alternatives to jail time.

The report’s recommendations are accompanied by helpful graphics, as well as examples of local and state governments successfully implementing alternatives to jail expansion. “We know that the answer to mass incarceration begins at the local level,” said Jones. “That’s why it’s critical to help cities and counties think beyond jail expansion when it comes to improving public safety.”

At a time when phone calls for the rest of us cost almost nothing, there is no reason to force the poorest families in Iowa to pay outlandish rates.

April 26, 2019

For immediate release — The Prison Policy Initiative has filed objections to five phone companies’ proposed phone rates for Iowa county jails. At a time when the cost of a typical phone call is approaching zero, phone providers in Iowa jails frequently charge incarcerated people and their families 30 cents per minute or more for a phone call. (And one provider charges as much as $4.41 for the first minute.)

In January, the Iowa Utilities Board required these providers to file rate disclosures – or “tariffs” – for state approval. By state statute, the Utilities Board must ensure that rates are just and reasonable and that “no unreasonable profit is made.” The Prison Policy Initiative’s research has found that phone calls from Iowa’s jails are among the most expensive in the nation, and more than four times as expensive as calls from the state’s prison system.

In February, the Prison Policy Initiative report State of Phone Justice uncovered the cost of phone calls in over 2,000 jails nationwide, explaining why sheriffs sign lucrative phone contracts that prey on people in jail and their families:

- Phone providers compete for jail contracts by offering sheriffs large portions of the revenue – and then charge exorbitant phone rates.

- Providers exploit sheriffs’ lack of experience with telecommunications contracts to slip in hidden fees that fleece consumers.

- State legislators, regulators and governors traditionally pay little attention to jails, even as they continue to lower the cost of calls home from state prisons.

The report found that calls home from Iowa jails are the 13th most expensive in the nation. “There is no reason to force the poorest families in Iowa to pay these outlandish rates, particularly at a time when phone calls for the rest of us cost almost nothing,” said Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

The objections were filed with the research assistance of volunteer attorney Stephen Raher, and the organization is now being represented pro bono before the Iowa Utilities Board by David Yoshimura of Faegre Baker Daniels in Des Moines.

The Prison Policy Initiative’s objections to the tariffs are available for: Global Tel*Link, Public Communications Services, Prodigy Solutions, Reliance Telephone of Grand Forks, and Securus.

Yesterday, the Iowa Utilities board granted our request to intervene and docketed the tariffs for further review. Further comments about the proposed tariffs are due May 13.

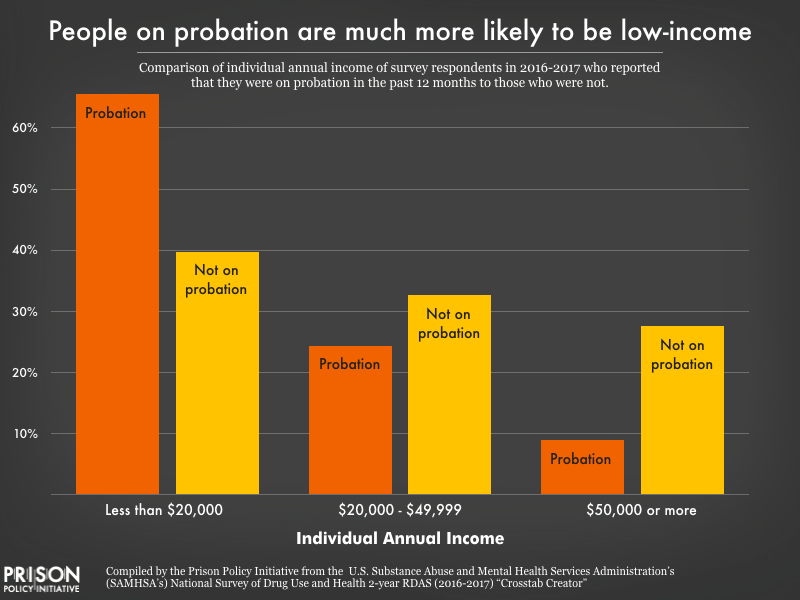

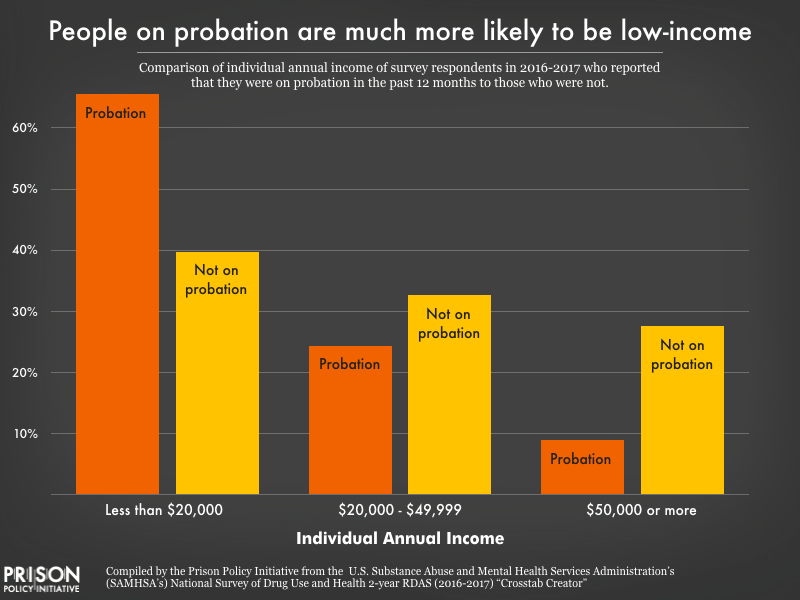

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren't, and steep monthly probation fees put them at risk of being jailed when they can't pay.

by Mack Finkel,

April 9, 2019

Over 3.6 million people are under probation supervision in the U.S., and in most states, they are charged a monthly probation fee. The problem? Many of them are among the nation’s poorest, and they can’t afford these fees. From our previous research in Massachusetts – and from reports from around the country – we know that the burden of probation fees often falls disproportionately on the poor. To determine the extent of the problem nationally, we examined the incomes of people on probation in a recent survey, the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Our analysis confirms that, nationwide, people on probation are much more likely than people not on probation to have low incomes.

The National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is an annual survey that asks respondents about a broad range of topics, including their annual income and whether they were on probation in the past 12 months. The inclusion of recent probation history in the survey makes it a valuable data source for criminal justice research; it comes closer than any other source to offering a recent, descriptive, nationally representative picture of the population on probation.1 Prof. Michelle Phelps of the University of Minnesota, for example, used this survey in her recent analysis comparing people on probation to those in prison, using educational attainment as a measure of economic status.

Our analysis of the 2016-2017 NSDUH data shows that people on probation typically have much lower incomes than those who aren’t on probation:

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the Appendix table.

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the Appendix table.

Key findings from our analysis include:

- Nationwide, two-thirds (66%) of people on probation make less than $20,000 per year.

- Nearly 2 in 5 people on probation (38%) make less than $10,000 per year, well below the poverty line.

- On the wealthier end of the spectrum, few people (9%) on probation have annual incomes of $50,000 or more, while more than a quarter (28%) of those not on probation make at least $50,000 per year.

Monthly probation fees may be just one of several fees that someone on probation has to pay regularly. As part of the conditions of their probation, an individual might have to pay court costs, one-time fees, monthly supervision fees, electronic monitoring costs, or any combination of these charges. Sometimes the law strictly defines the cost of these fees, and sometimes “reasonableness” is the only statutory guideline. Depending on the state, courts, departments of corrections, sheriffs’ departments, and the probation programs themselves can all collect revenue from these fees.

Even though the Supreme Court has said it is unconstitutional to incarcerate someone because they cannot afford to pay court ordered fines and fees, many courts effectively do just that. Judges often fail to consider the individual’s ability to pay (as opposed to their willingness to pay) and treat nonpayment of fees as a violation of probation. This flies in the face of many state statutes that allow incarceration only when there is evidence that the individual is able to pay but refuses.2 As a result, poor people on probation face a very real risk of being incarcerated because they can’t afford monthly fees. As the National Criminal Justice Debt Initiative shows, many state laws amount to “poverty penalties” and “poverty traps” and failure to pay can mean an extended probation sentence, driver’s license revocation, mandatory work program, or incarceration.

*In Massachusetts, the fees have two tiers, $50 for administrative and $65 for supervised probation. In Oklahoma, there are two separate monthly supervision fees, one up to $40 and another up to $20.

**Due to the small number of NSDUH respondents in Maine and South Carolina who were on probation at any time in the past 12 months, the survey does not make the necessary data available for those states as part of NSDUH’s efforts to protect respondents’ identities.

This table includes states where probation fees can cost $50 or more each month, and shows that in almost all of these states, over half (and even as many as 83%) of people on probation have annual incomes below $20,000. For them, unaffordable probation fees can lead to a cycle of poverty and incarceration. (Sources: Criminal Justice Debt Reform Builder, for probation fees, and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2-Year RDAS (2016-2017) for income data on the population experiencing probation in the past 12 months.)

| State |

Monthly supervision fee |

Portion of probation population

making less than $20,000 per year |

| Colorado |

Up to $50 |

48% |

| Idaho |

Up to $75 |

67% |

| Illinois |

$50 |

65% |

| Louisiana |

$71 to $121 |

69% |

| Maine |

$10 to $50 |

NA** |

| Massachusetts |

$50 or $65* |

52% |

| Michigan |

Up to $135 |

67% |

| Mississippi |

$55 |

67% |

| Montana |

At least $50 |

64% |

| New Mexico |

$15 to $150 |

83% |

| North Dakota |

$55 |

77% |

| Ohio |

Up to $50 |

62% |

| Oklahoma |

Up to $60* |

75% |

| South Carolina |

$20 to $120 |

NA** |

| Washington |

Up to 100 |

50% |

Such high fees – and high stakes – defeat the purpose of probation. In theory, probation (often touted as an “alternative” to incarceration) allows people to continue to work and manage family responsibilities while under supervision. But people faced with unaffordable fees are more likely to violate the conditions of supervision, experience housing and food instability, and struggle to support their children. And when failure to pay is treated as a violation of probation, individuals can be incarcerated, have their probation extended, and/or lose public benefits like food stamps and supplemental security income.

Louisiana is an especially punishing state for poor people on probation. The average probation sentence there lasts three years, and probation fees are among the highest in the country, at $71 to $121 per month, even though 69% of people on probation make less than $20,000 per year. Data from a report by the state’s Justice Reinvestment Task Force shows just how unreasonable these fees are. In Louisiana in 2015:

- While under community supervision, the average person owed $1,740 in supervision fees alone. (Supervision fees were just one type of a number of court-ordered fines and fees.)

- On average, people under supervision could only pay about half of the imposed fees; at the end of their supervision term, the average person still owed 48% of their supervision fees.

Louisiana’s probation system creates impossible debts that unfairly burden poor probationers. As in many states, failure to pay can lead to license suspensions, extension of supervision terms, and incarceration.

Fortunately, this is slated to change. Under a new law going into effect in August 2019, Louisiana courts will hold hearings on ability to pay, and defendants may have their fees waived or reduced if the court finds that fees will cause substantial financial hardship. While the fees are still far too high, the new law offers hope for low-income people on probation. (It’s worth noting that judges, district attorneys, and court clerks whose offices benefit from the fees have fought to delay the implementation of the law.)

As long as probation sentences include unreasonable fees and harsh punishments for failure to pay them, probation will continue to punish people just for being poor. Some states have begun to implement reforms to reduce the unnecessary incarceration and other unintended consequences of their probation fee systems. But as our analysis shows, this is a widespread problem that every state imposing probation fees should address. States must acknowledge that people on probation are mostly low-income, and driving them further into poverty through monthly fees is cruel and counterproductive.

Appendix table: Percentage of Probation Population vs. Non-Probation Population in Each Category of Personal Annual Income (Source: NSDUH 2016-2017)

| Personal Annual Income |

Less than $10,000 |

$10,000 to $19,999 |

$20,000 to $29,999 |

$30,000 to $39,000 |

$40,000 to $49,999 |

$50,000 to $74,999 |

$75,000 or more |

| On probation in the past 12 months |

37.9% |

27.7% |

13.4% |

7% |

5% |

6.1% |

2.9% |

| Not on probation in the past 12 months |

21.8% |

17.9% |

13% |

10.7% |

9% |

12.3% |

15.3% |

A merger between the two companies would have curtailed the ability of prisons and jails to choose a phone provider, to the detriment of incarcerated people and their families.

April 2, 2019

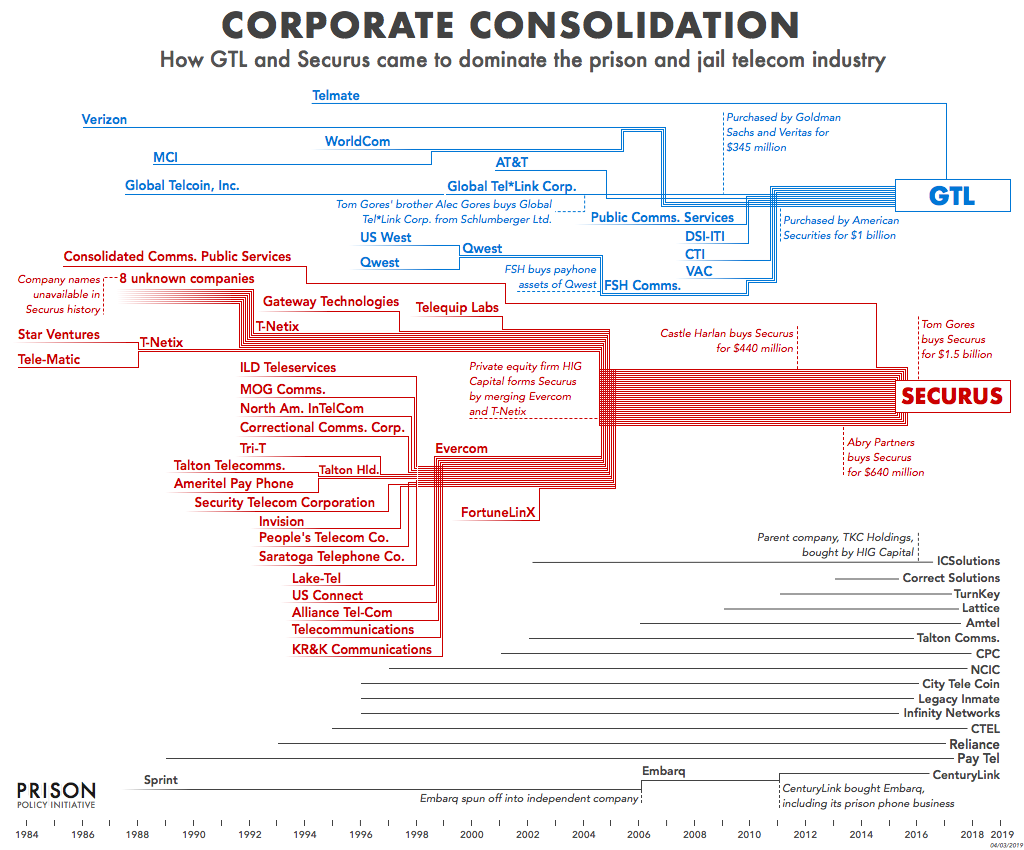

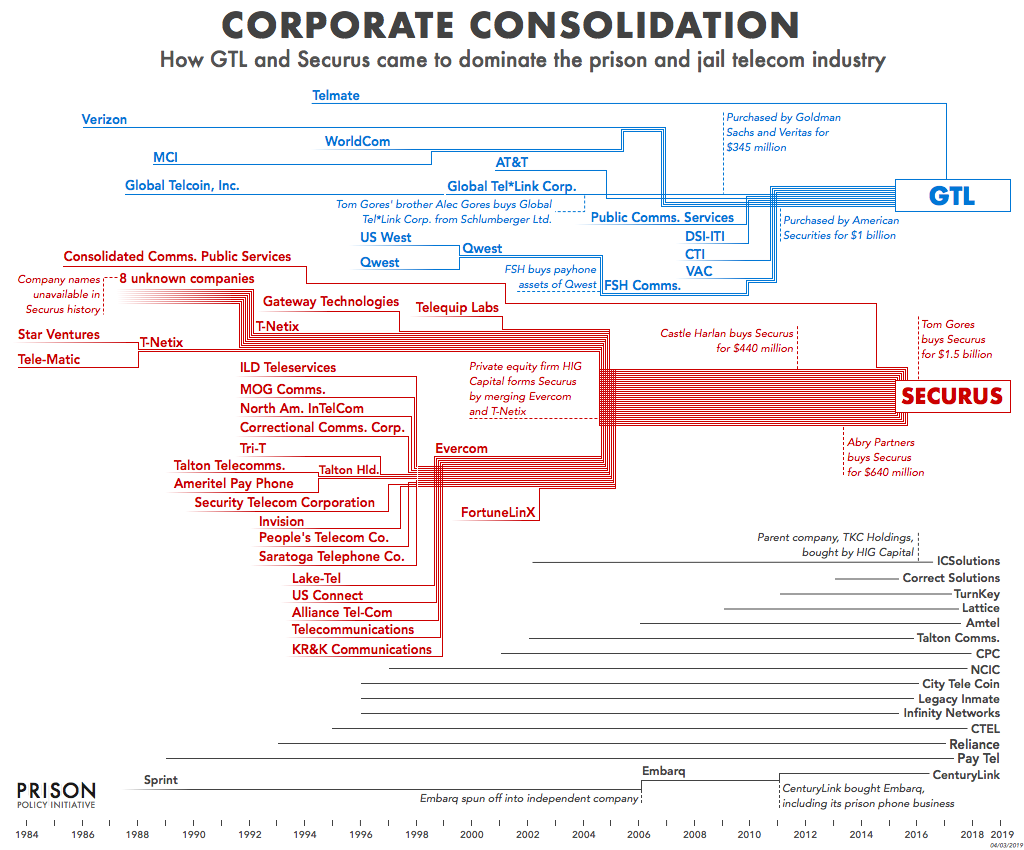

Easthampton, Mass. – Prison phone industry giant Securus has abandoned its attempt to purchase ICSolutions, the industry’s third largest company, after the Federal Communications Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division signaled that they would likely block the deal. The merger would have effectively handed the market for prison and jail phone services over to Securus and its last major competitor, GTL.

“Based on a record of nearly 1 million documents comprised of 7.7 million pages of information submitted by the applicants, as well as arguments and evidence submitted by criminal justice advocates, consumer groups, and other commenters, FCC staff concluded that this deal posed significant competitive concerns and would not be in the public interest,” said FCC chairman Ajit Pai in a press release.

“Securus and ICS [Inmate Calling Solutions] have a history of competing aggressively to win state and local contracts by offering better financial terms, lower calling rates, and more innovative technology and services. This merger would have eliminated that competition, plain and simple,” said Makan Delrahim, Assistant Attorney General of the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division in a press release. “The companies’ decision to abandon this deal is the right outcome – correctional facilities, inmates and their friends and families will continue to benefit from the robust competition between these firms.”

“All too often, calls home from jails cost an unconscionable $1/minute,” said Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. “Had the companies merged, facilities would have had a harder time negotiating contracts with lower rates for families – which, thanks to our movement’s ongoing advocacy, they’re finally beginning to do.”

In our objection to the merger, filed in July 2018 with a coalition of groups working for prison phone justice represented by probono attorneys Davina Sashkin and Cheng-yi Liu, we argued that the FCC should stop the merger.

We argued that Securus’ history of repeatedly flouting commission rules – including deliberately misleading the FCC during a similar review last year, for which it was punished with an unprecedented $1.7 million fine – made it ineligible to purchase one of its competitors. We explained that the company has repeatedly tried to circumvent regulation in order to increase its profits from prison phone calls, and as recently as May 2018 was caught enabling illegal cell phone tracking.

Our filing included a detailed analysis of the concentration of the prison and jail telephone industry. We calculated market share in two different ways; by either measure, Securus and GTL were poised to control between 74% and 83% of the market. Except for ICSolutions – which Securus was seeking to acquire – no other company had above 3% market share.

Below is a historical timeline originally prepared for our report State of Phone Justice: Local jails, state prisons and private phone providers, showing how aggressively Securus and GTL have been gobbling up their competitors:

For more information about this timeline, the companies, their respective sizes, the role of companies like CenturyLink that operate only in partnership with Securus and ICSolutions, or the historical role of AT&T and Verizon, see our report, the footnotes, and appendices to State of Phone Justice: Local jails, state prisons and private phone providers.

Updated April 3, 2019 10am with FCC press release and 1pm with the Department of Justice’s press release.

California's AB 964 would require in-person visits in all California jails

by Bernadette Rabuy,

March 30, 2019

For the past few years, California policymakers have been at hard work to protect in-person jail visitation from sheriffs and private companies who are eager to replace crucial human contact with impersonal video chats. While legislators were successful in preventing jails who provided in-person visits in January 2017 from later eliminating them, jails that had already banned in-person visits are permitted to continue their video-only policies.

That could change this legislative cycle thanks to Assembly Member Medina’s AB 964. AB 964 would require that all California jails provide in-person visits. Specifically, jails that are currently exempted would need to restore in-person visits by 2025.

The Assembly Public Safety Committee will be voting on AB 964 on April 2. We submitted a comment, encouraging committee members “to recognize and support the positive role families play in rehabilitation” and, more importantly, that “human beings need in person visits.”

The Mass. Senate is considering building a new women's jail. We offer a number of reasons why this is a bad idea.

by Wendy Sawyer,

March 29, 2019

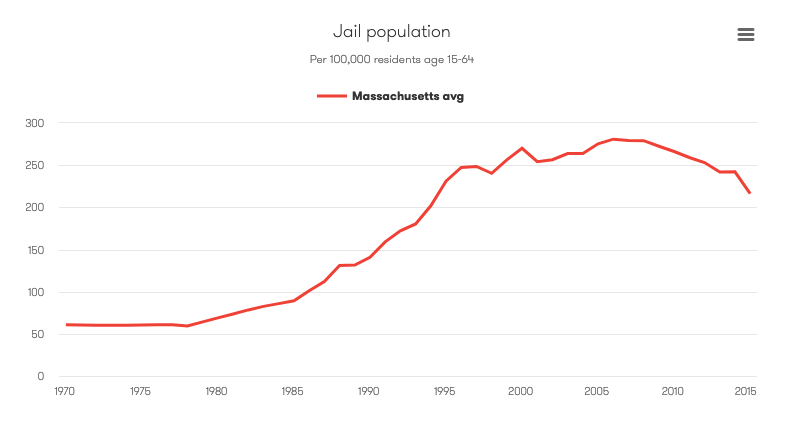

The Massachusetts Senate is once again considering construction of a new jail for women in Middlesex County. But I would caution against any expansion of correctional facilities without first reckoning with the inherent harms of jail incarceration and exploring better alternatives.

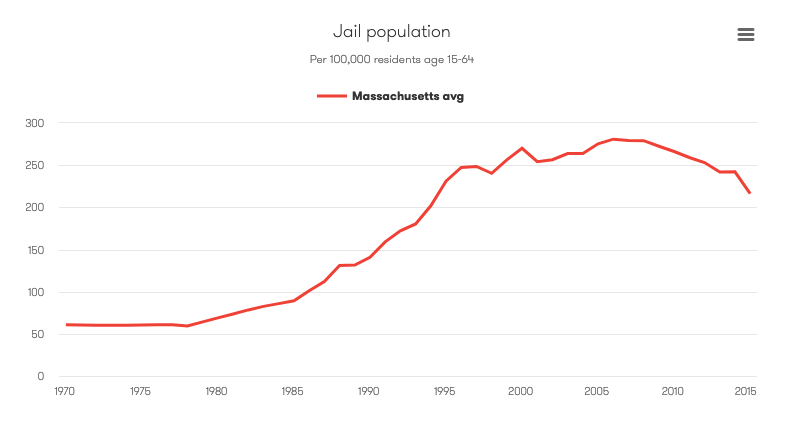

The proposal – Senate 1851 – would “establish a commission to identify a suitable location for a justice complex” in Middlesex County. I find it interesting that the commission is to identify a location, rather than consider whether a jail is needed at all. According to the text of the bill, this proposal is in line with a law passed in 2008 to expand jail capacity. But that law was passed in the wake of the state’s highest-ever rate of jail incarceration; since then, the state’s jail rate has seen a steady decline. This begs the question: why would the state need more capacity, when jail rates are down?

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that jail incarceration rates in Massachusetts have fallen over the past decade.

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that jail incarceration rates in Massachusetts have fallen over the past decade.

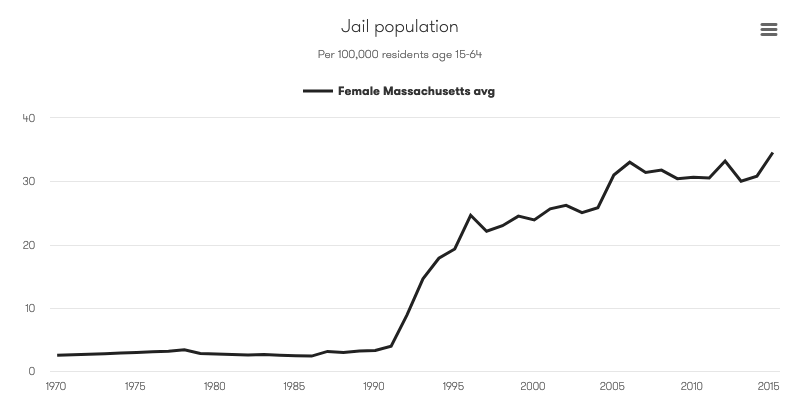

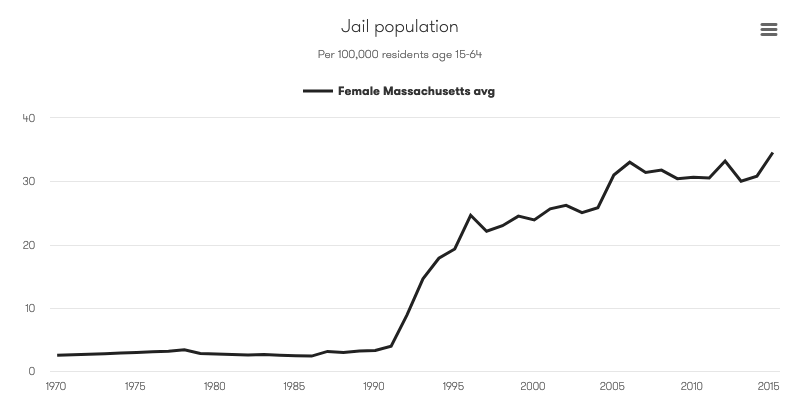

Despite the overall downward trend in the state’s jail rate, two groups have been jailed at steady or increasing rates: women and people being detained pretrial – and these are the two populations being used to justify the “need” for a new jail.

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that the female jail rate in Massachusetts has risen steadily since the early 1990s.

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that the female jail rate in Massachusetts has risen steadily since the early 1990s.

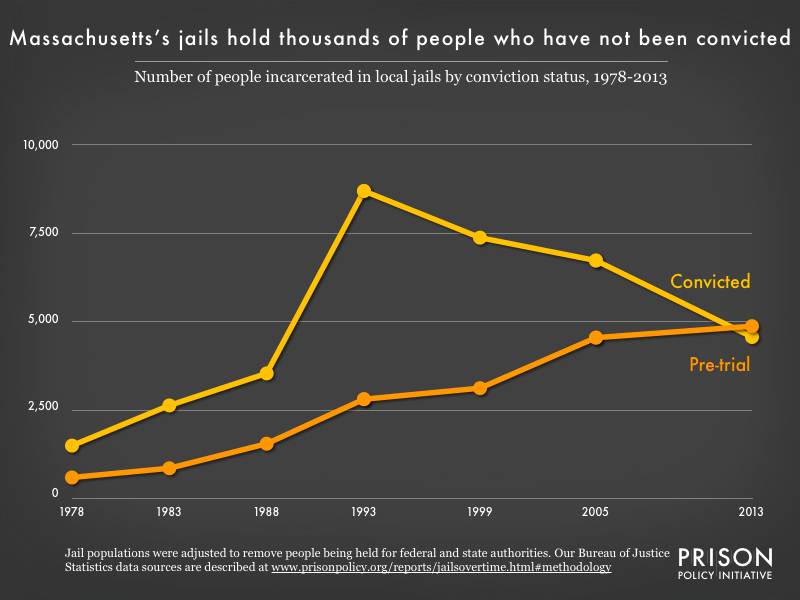

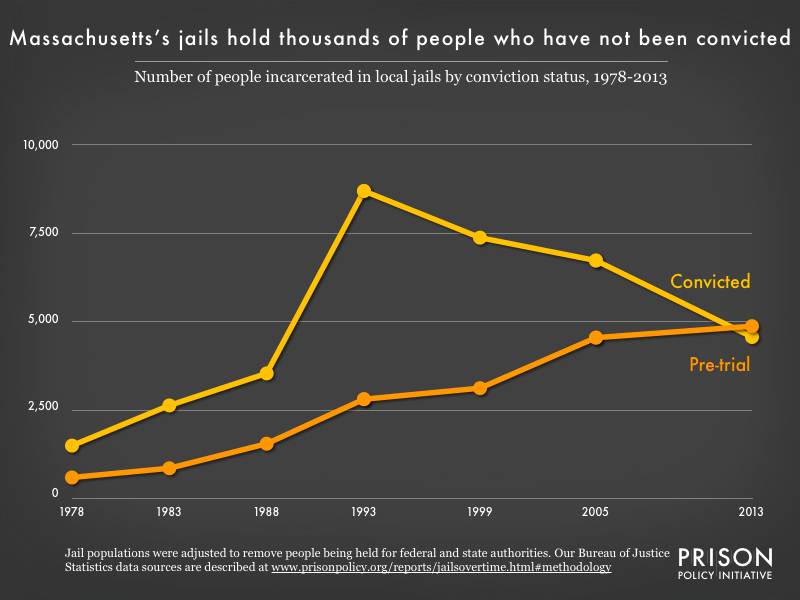

The pretrial population in Massachusetts jails has increased for decades, while the number of people serving sentences there has fallen dramatically since 1993.

The pretrial population in Massachusetts jails has increased for decades, while the number of people serving sentences there has fallen dramatically since 1993.

But despite the growth in the female and pretrial jail populations, there are some important arguments against building a new jail to hold these groups.

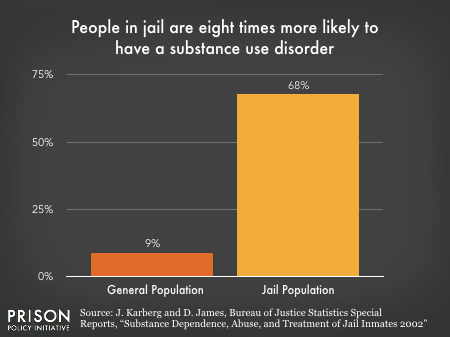

First, jails are uniquely harmful to women, and their needs are better met by community-based programs and services. Women in jails have higher rates of mental health and substance use disorders, and often have a history of abuse or other trauma; incarceration more often exacerbates these problems than alleviates them (for more information, see the “Context” sidebar in our 2018 report). As of December 2018, the Massachusetts Department of Corrections (DOC) reported that “74% [of women held by the DOC] were open mental health cases, 15% had a serious mental illness (SMI), and 56% were on psychotropic medication” – all rates roughly double those of the male population. Women in jails (especially women of color) are also poorer, on average, than their male counterparts, and therefore often are detained pretrial because they can’t afford even low bail amounts. Furthermore, separation from children leads many women to accept plea deals just to get out of jail sooner, which in turn leaves them with criminal records that may not reflect actual guilt or innocence.

Second, pretrial detention leads to worse outcomes, from high risk of suicide to increased likelihood of conviction, longer sentences, and reoffending. Yet pretrial detention has driven all of the jail growth in the U.S. over the last 20 years, which means that jails – like the one being proposed – are being built because more people who have not been convicted and are legally presumed innocent are being locked up. This trend reflects an increasing reliance on money bail – essentially, wealth-based release decisions – rather than an increase in “dangerousness” or flight risk. According to DOC data, the female pretrial population held by the DOC has increased 18% since 2010. If Massachusetts wants to relieve jail overcrowding, it should start by minimizing the number of people held pretrial, especially those who are there because they can’t afford bail.

Another problem that should be addressed before expanding jail capacity is the racial disparity evident in the state’s female pretrial population. As of Jan. 1, 2018, nearly a third (32%) of the women held by the DOC (in Framingham) were being detained pretrial. However, this proportion varied by race and ethnicity. 44% of Hispanic women and 35% of Black women held by the DOC, versus 31% of “Other” and 29% of white women, were held pretrial.

The idea to build a new women’s jail is not a new one. For years, a handful of Massachusetts counties have sent women detained pretrial to the women’s prison, MCI-Framingham, because they didn’t have separate jail space for women in the county jails. And for years, MCI-Framingham was overcrowded for precisely that reason. In 2007, the state opened a new jail for women farther west, and sent women from counties without separate women’s facilities that were west of Worcester to the new jail to await trial or serve their sentences. The result? Women jailed there were farther from crucial contacts, including their families and children, and their lawyers – which in turn made it harder to prepare their defense. Now, lawmakers want to build again, this time near the existing Framingham facility in southern Middlesex County.

The legislators behind the new jail project undoubtedly see a new jail as an “upgrade” for the state’s incarcerated women, since it would alleviate crowding and would be more updated housing than the nearly 150-year-old prison. But the real solution for women in jails would be to return to their communities. They would be better served awaiting trial at home, participating in diversion programs, and getting needed treatment and support for underlying problems through community-based programs. If legislators care about improving conditions for justice-involved women, they should focus on investing in community services and alternatives to incarceration that interrupt women’s distinct pathways to prison – not just building them newer, bigger, jails.

In the past two decades, the total number of arrests in the U.S. has dropped by more than 30 percent, from

In the past two decades, the total number of arrests in the U.S. has dropped by more than 30 percent, from

As with women’s share of arrests, women’s share of police encounters that involve the use or threat of force has increased significantly since 1999.

As with women’s share of arrests, women’s share of police encounters that involve the use or threat of force has increased significantly since 1999. Women also make up a larger percentage of all people searched during traffic stops. In 1999, men who were stopped while driving were about four times as likely to be searched during the stop than women; by 2015, men were just twice as likely to be searched. The narrowing of this gap reflects a decline in searches of men; for women, the share of stops that resulted in search remained the same, at 2.3 percent. In 1999, police searched the driver or vehicle in 9.4 percent of stops of men, which amounts to over one million stops involving a search. In 2015, however, the percentage of stops involving male drivers that resulted in search or arrest dropped by half, to 4.7 percent – or over 500,000 stops. Female drivers, however, saw no change in their likelihood of search or arrest during a traffic stop.

Women also make up a larger percentage of all people searched during traffic stops. In 1999, men who were stopped while driving were about four times as likely to be searched during the stop than women; by 2015, men were just twice as likely to be searched. The narrowing of this gap reflects a decline in searches of men; for women, the share of stops that resulted in search remained the same, at 2.3 percent. In 1999, police searched the driver or vehicle in 9.4 percent of stops of men, which amounts to over one million stops involving a search. In 2015, however, the percentage of stops involving male drivers that resulted in search or arrest dropped by half, to 4.7 percent – or over 500,000 stops. Female drivers, however, saw no change in their likelihood of search or arrest during a traffic stop.

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the

People on probation are much more likely to be low-income than those who aren’t on probation, and steep monthly probation fees often put them at risk of being jailed when they can’t pay. For a more detailed comparison, see the

The Vera Institute of Justice’s

The Vera Institute of Justice’s  The Vera Institute of Justice’s

The Vera Institute of Justice’s  The pretrial population in Massachusetts jails has increased for decades, while the number of people serving sentences there has fallen dramatically since 1993.

The pretrial population in Massachusetts jails has increased for decades, while the number of people serving sentences there has fallen dramatically since 1993.