The Gender Divide: Tracking Women's State Prison Growth

By Wendy Sawyer

January 9, 2018

The story of women’s prison growth has been obscured by overly broad discussions of the “total” prison population for too long. This report sheds more light on women in the era of mass incarceration by tracking prison population trends since 1978 for all 50 states. The analysis identifies places where recent reforms appear to have had a disparate effect on women, and offers states recommendations to reverse mass incarceration for women alongside men.

Across the country, we find a disturbing gender disparity in recent prison population trends. While recent reforms have reduced the total number of people in state prisons since 2009, almost all of the decrease has been among men. Looking deeper into the state-specific data, we can identify the states driving the disparity.

In 35 states, women’s population numbers have fared worse than men’s, and in a few extraordinary states, women’s prison populations have even grown enough to counteract reductions in the men’s population. Too often, states undermine their commitment to criminal justice reform by ignoring women’s incarceration.

Women have become the fastest-growing segment of the incarcerated population, but despite recent interest in the alarming national trend, few people know what’s happening in their own states. Examining these state trends is critical for making the state-level policy choices that will dictate the future of mass incarceration.

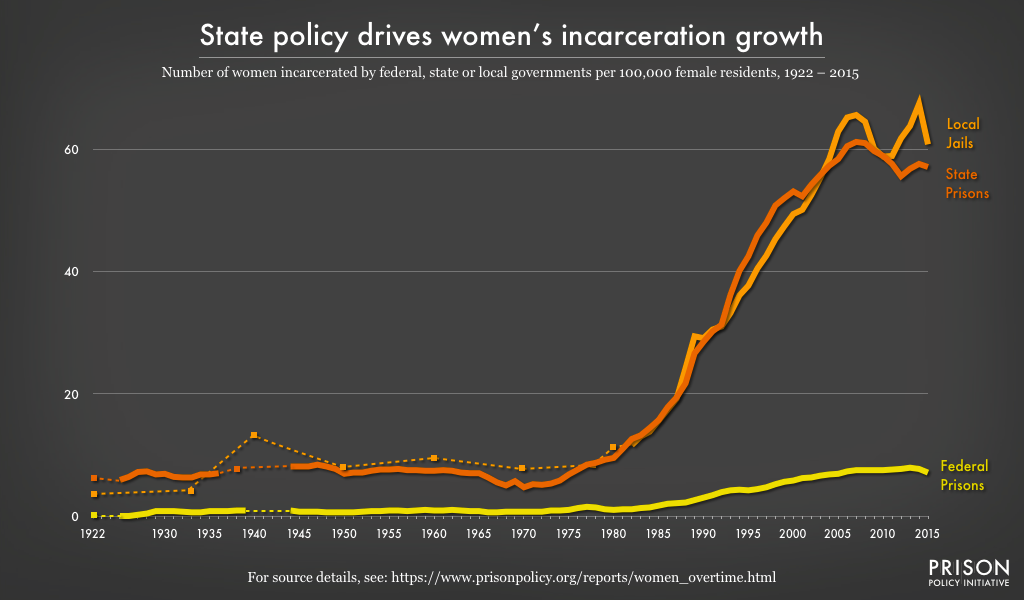

Figure 1 Women’s incarceration rates have grown dramatically since the late 1970s. But in contrast to the total incarcerated population — which is overwhelmingly male — women’s jail rates have grown about equally to their state prison rates. (See as raw numbers. The data behind both graphs is in Table 1.)

Figure 1 Women’s incarceration rates have grown dramatically since the late 1970s. But in contrast to the total incarcerated population — which is overwhelmingly male — women’s jail rates have grown about equally to their state prison rates. (See as raw numbers. The data behind both graphs is in Table 1.)

National trends in women’s state prison growth

Nationally, women’s incarceration trends have generally tracked with the overall growth of the incarcerated population. Just as we see in the total population, the number of women locked up for violations of state and local laws has skyrocketed since the late 1970s, while the federal prison population hasn’t changed nearly as dramatically. These trends clearly demonstrate that state and local policies have driven the mass incarceration of women.

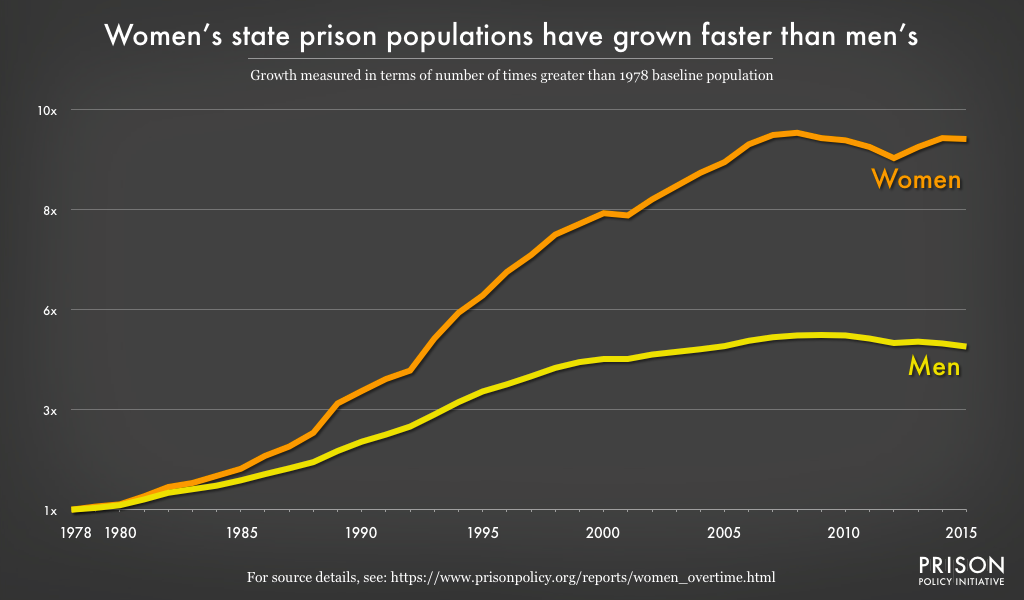

Figure 2 Since 1978, the number of women in state prisons nationwide has grown at over twice the pace of men, to over 9 times the size of the 1978 population.

Figure 2 Since 1978, the number of women in state prisons nationwide has grown at over twice the pace of men, to over 9 times the size of the 1978 population.

There are a few important differences between men’s and women’s national incarceration patterns over time. For example, jails play a particularly significant role in women’s incarceration (see sidebar, “The role of local jails”). And although women represent a small fraction of all incarcerated people,3 women’s prison populations have seen much higher relative growth than men’s since 1978. Nationwide, women’s state prison populations grew 834% over nearly 40 years — more than double the pace of the growth among men.45

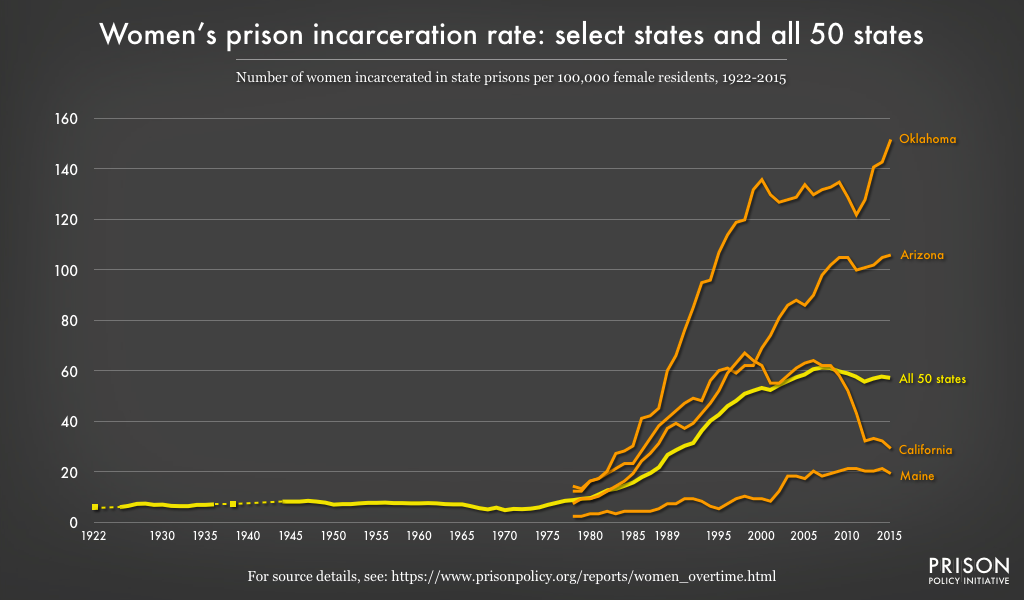

Figure 3 The national trend of women’s state prison incarceration obscures a tremendous amount of state-to-state variation. State-level data reveals that some states, like Oklahoma and Arizona, have seen much more dramatic growth in women’s prisons, while others have kept rates well below the national average.

Figure 3 The national trend of women’s state prison incarceration obscures a tremendous amount of state-to-state variation. State-level data reveals that some states, like Oklahoma and Arizona, have seen much more dramatic growth in women’s prisons, while others have kept rates well below the national average.

While the national trend provides helpful context, it also obscures a tremendous amount of state-to-state variation. The change in women’s state prison incarceration rates has actually been much smaller in some places, like Maine, and far more dramatic in others, like Oklahoma and Arizona. A few states, including California, New York, and New Jersey, reversed course and began decarcerating state prisons years ago. The wide variation in state trends underscores the need to examine state-level data when making criminal justice policy decisions. To that end, this report includes graphs of prison populations and incarceration rates over time by gender for all 50 states.16

Recent efforts to reverse growth have worked better for men than women

Perhaps the most troubling finding about women’s incarceration is how little progress states have made in curbing its growth — especially in light of the progress made to reduce men’s prison populations.

Of course, some progress has been made toward slowing and even reversing the growth of state prison populations since they peaked nationally in 2009.17 But this progress has been uneven, impacting men more than women. The total number of men incarcerated in state prisons fell more than 5% between 2009 and 2015, while the number of women in state prisons fell only a fraction of a percent (0.29%).18

State-level trends

At the state level, the disparate effects of justice reforms for men and women are even more dramatic. In terms of relative (percent) change in the numbers of women and men in state prisons since the total state prison population peaked in 2009,19 women have fared worse than men in 35 states. In these states, women’s prison populations have either:

- grown, while men’s populations have declined,

- continued to outpace the growth of men’s populations, or

- declined, but less dramatically than men’s populations declined.

In many states, treating women’s incarceration as an afterthought has, in effect, held back efforts to decarcerate.

Key:

Figure 4 State prison populations nationwide peaked in 2009. Since then, women’s prison populations have fared worse than men’s in 35 states. All 50 states are categorized by patterns of gender disparities above. (The data behind this graphic is in Table 2.)

In 8 states, ignoring women’s incarceration has clearly worked against state efforts to reduce prison populations: women’s populations continued to grow, unchecked, while men’s populations declined after 2009. Michigan reduced the number of men incarcerated in its state prisons by 8% between 2009-2015, but counterproductively incarcerated 30% more women over the same period. Texas cut its men’s prison population by 6,000 — but backfilled its prisons with an additional 1,100 women. Idaho backfilled half of the prison beds it emptied from its men’s prisons by adding 25% more women to its prisons. And in Iowa and Washington, the modest reductions in the men’s populations were completely cancelled out by growth in the women’s populations.

More commonly — in 19 states — women’s state prison populations continued to outpace men’s prison population growth after 2009. In some of these states, the incarceration of women is actually driving state prison growth. In Kentucky, Missouri, Nevada, and New Hampshire, almost half of total prison growth between 2009-2015 was in women’s prisons, despite their much smaller populations. In North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, and Virginia, more women were added to state prison populations than men. In these 4 states, between 52% and 97% of total state prison growth was driven by the growth in women’s populations.

Consistent with the national trend, women’s prison populations have declined — but less dramatically than men’s populations — in 8 states since 2009. In Massachusetts and New York, for example, the men’s populations were cut by over 10% while the women’s populations declined by just 5%.20

In a few states, women are decarcerating faster than men

Of course, it is not universally the case that women have fared worse than men when it comes to decarceration of state prisons. In 14 states, changes in women’s incarceration are actually slowing the growth of state prison populations, and sometimes even driving decarceration. In Hawaii, Louisiana, and Mississippi, reductions in the women’s population accounted for 15%-25% of each state's total prison population reduction; in Rhode Island, nearly half of the total reduction was among women. Utah stands out as the only state where there was a significant (11%) reduction in the women’s prison population, which was enough to counteract the slight growth among men. For researchers interested in policy changes that both reduce women’s incarceration and advance more far-reaching justice reforms, these special cases may be informative.

Why is progress slower for women?

Although we can identify some of the reasons for the outsized growth of women’s incarceration (see Context sidebar), it’s harder to say why progress toward reversing prison growth has been slower for women. It’s harder still to identify potential policy solutions to the gender divide, especially when the divide is very likely related to broader systemic shifts that affect women’s prospects.21 However, some gender differences in policy and practice have already been identified that impact the likelihood of — and harm caused by — criminal justice involvement for women. As a starting point, policymakers and future researchers should explore the scope, impact, and potential solutions to these issues:

- While they are incarcerated, women may face a greater likelihood of disciplinary action — and more severe sanctions — for similar behavior when compared to men.22 Disciplinary action works against an incarcerated woman’s ability to earn time off of her sentence and against her chances of parole.

- Fewer diversion programs are available to women. In Wyoming, for example, a “boot camp” program that allows first-time offenders to participate in a six-month rehabilitative and educational program in lieu of years in prison is only open to men. Because no similar program is available for women in the state, women in Wyoming can face years of incarceration for first-time offenses while their male peers return quickly to the community.

- States continue to “widen the net” of criminal justice involvement by criminalizing women’s responses to gender-based abuse and discrimination. This report has already touched on how overcriminalization of drug use and peripheral involvement in drug networks has driven women’s prison growth (see Context sidebar). Other policy changes have led to mandatory or “dual” arrests for fighting back against domestic violence, increasing criminalization of school-aged girls’ misbehavior — including survival efforts like running away — and the criminalization of women who support themselves through sex work.

The need for targeted attention to women’s incarceration

Women’s incarceration impacts the broader picture of mass incarceration, especially after decades of rapid growth. In some states, the escalating incarceration of women now drives prison growth, while in other states, it dampens the effect of prison reforms. Ignoring the problem holds back progress, while further analysis of gender effects is likely to yield new ideas that can accelerate the reduction of prison populations.

But separately from the bigger picture of mass incarceration, women’s incarceration demands more attention because of the distinct ways in which prisons and jails fail women and their families. Research consistently shows that incarcerated women face different problems than men — and prisons often make those problems worse. While not a comprehensive list, some of the major issues facing incarcerated women include:

- Women are more likely to enter prison with a history of abuse, trauma, and mental health problems (see Context sidebar). But even in the “secure” prison environment, women face sexual abuse by correctional staff or other incarcerated women,23 and are more likely than men to experience serious psychological distress. (This is to say nothing of girls who are victimized in juvenile facilities or the abuse of incarcerated transgender women.)24 Treatment for trauma and mental health problems is often inadequate or unavailable in prisons.

- Women have different physical health needs, including reproductive healthcare,25 management of menopause, nutrition, and very often treatment for substance use disorders. Again, the health systems in prisons — designed for men — frequently fail to meet these basic needs.

- Most women in prison (62%) are mothers of minor children. These women are more likely than fathers in prison to be the primary caretakers of their children, so the increasing number of women in prisons means more and more family disruption and insecurity.26 Incarcerated women and their families suffer from lack of face-to-face contact: because there are fewer women’s prisons, women are more likely to be held in prisons located far from home, making visits difficult and expensive. To make matters worse, if children are placed in foster care when their mother is incarcerated, her prison sentence can sever family ties permanently.

- Economically, women with a history of incarceration face particularly daunting obstacles when they return to their communities. Even before they are incarcerated, women in prison earn less than men in prison, and earn less than non-incarcerated women of the same age and race.27 Women’s prisons do not meet the need or demand for vocational and educational program opportunities.28 And once released, the collateral consequences of incarceration make finding work, housing, and financial support even more difficult.

Conclusion

The mass incarceration of women is harmful, wasteful, and counterproductive; that much is clear. But the nation’s understanding of women’s incarceration suffers from the relative scarcity of gender-specific data, analysis, and discourse. As the number of women in prisons and jails continues to rise in many states — even as the number of men falls — understanding this dramatic growth becomes more urgent. What policies fuel continued growth today? What part does jail growth play? Where is change needed most now, and what kinds of changes will help? This report and the state data it provides lay the groundwork for states to engage these critical questions as they take deliberate and decisive action to reverse prison growth.

Recommendations

Because, as this report demonstrates, all states arrived at the mass incarceration of women by different means and some states are further ahead of others at reversing course, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. As all states begin to examine their own patterns to develop an effective strategy to reduce prison populations, they would benefit from exploring these ten recommendations drawn from the experiences of other states.

- Most generally, criminal justice agencies must take a gender-responsive approach to meet the needs of justice-involved women. Considering the large number of women whose experiences with trauma, substance use disorders, and mental health problems have led to their contact with the criminal justice system, alternatives to incarceration that treat these underlying issues are likely more appropriate for many women than prisons, where these problems are often exacerbated. When policymakers and administrators understand and acknowledge women’s unique pathways to criminal justice involvement, “the criminalization of women’s survival behaviors”29 may shift to treatment and services as more effective crime prevention strategies. Correctional agency programming and staff training should also be “trauma-informed”, doing no harm at a minimum, and recognizing that most of the women in their care are victims as well as “offenders”.

To be clear, the way to better serve women in prison is not to build better prisons30 — but to to ensure women are included in reforms that move people away from prisons toward better solutions. The most effective changes will reverse the growth of all incarcerated populations, without leaving women behind.

To reduce the number of people entering the correctional system:

- State and local governments should expand the use of diversion strategies and programs at each possible stage, from pre-arrest to re-arrest. From the first moment of police contact, opportunities exist to redirect individuals away from the criminal justice system towards rehabilitative treatment and services. Police, prosecutors, and judges should be trained and encouraged to identify individuals whose mental health, substance use, or other personal needs could be better served in alternative settings in their community — which includes most criminal justice-involved women. Police should work with local health and social service providers to direct people in crisis to appropriate services instead of jail, as many have done with “crisis intervention team” programs. Policymakers should expand the use, eligibility, and accessibility31 of problem-solving courts32 (drug court, mental health court, re-entry focused courts, etc.) and prosecutor-led pretrial diversion programs33 to shift the treatment of public health and social problems to professional service providers outside of the criminal justice system.

- States should reclassify criminal offenses and change responses to low-level offenses to avoid overcriminalizing behaviors that pose little threat to public safety. Misdemeanors that don’t threaten public safety should be turned into non-jailable infractions; citations should be issued in lieu of arrest for many low-level offenses; and fully-funded treatment-based diversion programs should be made default responses instead of incarceration. One of the most egregious examples of overcriminalization of women is mandatory dual arrest, which in effect criminalizes victims of domestic violence.

- Federal, state, and local governments should fully fund indigent criminal defense. Most criminal defendants are too poor to afford a private attorney, yet budget cuts in state after state have left public defenders’ offices overworked and without adequate resources. Public defenders play a key role in keeping people out of jail and prison, and their role should be funded comparably to prosecution. Public defense is particularly important for women who have limited financial resources to afford private attorneys.

- States should change policies that criminalize poverty or that create financial incentives for unnecessarily punitive sentences. States should encourage judges to use non-monetary sanctions, rather than fines and fees, and ensure that judges hold hearings on ability to pay before assessing fees. States and local governments should stop jailing people for failure to pay fines and fees they can’t afford and expand waiver systems, payment plans, and community service options in ways that are mindful of a person’s caregiving obligations, which disproportionately fall on women. Room and board fees and for-profit probation systems should be eliminated to remove obvious financial incentives for prolonging correctional control. Finally, and crucially, states should eliminate money bail, which unfairly leads to more detention and worse outcomes for poor defendants.

To reduce the likelihood and length of incarceration for those with convictions who pose little public safety risk:

- States should reform sentencing policies to restore judicial discretion, avoid over-sentencing, and encourage earlier release for low-risk individuals. Mandatory minimum sentences and “three strikes” or habitual offender laws should be repealed so that sentences can be crafted thoughtfully to match the circumstances of each individual, his or her crime, and any victims. Until mandatory minimum laws can be repealed, sentencing “safety valve” laws can be enacted to allow judges to deviate from mandatory minimums under certain conditions.34

- State and local governments should limit the frequency, conditions, and length of community supervision to avoid unnecessarily widening the net of correctional control. While pretrial, probation, and parole supervision allow individuals to remain in their community, the conditions of supervision can be counterproductive when they are especially numerous, expensive, or difficult to balance with family or work obligations. In this way, sentences to community supervision can actually set people up to fail and lead to more incarceration. Sentences to community supervision should only be used as a proportionate response, not as a catch-all solution.

- States should encourage earlier release from prison by expanding the use of incentives to reward compliance and paroling people who are unlikely to reoffend. “Truth in sentencing” laws should be repealed so that correctional staff can take full advantage of good time credits and parole as management tools, and incarcerated people who are unlikely to reoffend can be released earlier.35 States should adopt presumptive parole policies that would make people eligible for parole as soon as they serve their minimum sentence, and expand parole for older and seriously ill people who are unlikely to reoffend.

To reduce recidivism and support women with convictions in the community:

- State and local governments should implement and fund gender-responsive strategies to support women’s reentry. Women returning home from prison have a greater need for housing, employment, and financial support services than men,36 and have particular needs related to trauma and substance use, physical health, and parental stress and responsibilities.37 Wraparound services that start with pre-release planning and connect to post-release case management and services in the community can help stabilize women and families and break the cycle of criminal justice involvement.

- States should eliminate collateral consequences of criminal convictions that present barriers to successful reentry. Laws that automatically exclude people with criminal convictions from public benefits, housing, driver’s licenses, civic participation, and educational and employment opportunities are counterproductive; they make it harder for people of limited economic means to succeed and avoid further criminal justice involvement.38 Similarly, penalizing failure to pay criminal justice debts (or legal financial obligations) with incarceration or longer probation terms contributes to prison growth.39 Criminal justice-involved women are among the poorest members of society, so these additional barriers hit women particularly hard. Legislators should repeal laws that create legal and financial barriers to success, and support initiatives that enhance opportunities for people with convictions.

State graphs

Methodology

Graph data sources:

The individual graphs of each state’s trends from 1978-2015 are based on data from the Bureau of Bureau of Justice Statistics, Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) – Prisoners, showing:

- For rates: the yearend imprisonment rates of jurisdictional populations with sentences greater than one year for each state, by sex

- For population counts: the yearend jurisdictional population with sentences greater than one year for each state, by sex

This report contains several graphs (Figures 1, 2, and 3) with source information that is too extensive to fit on the graphs themselves, so the details are provided here.

The graph titled “State policy drives women’s incarceration growth” (Figure 1) is drawn from a number of sources to show women’s incarceration rates from 1922 to 2015 for local jails, state prisons, and federal prisons. For each year, we used correctional data to calculate the incarceration rates per 100,000 female residents in the U.S., using population data from the Census Bureau. The correctional data we used is described below.

The state and federal prison data was drawn from the following sources:

- 1922 to 1977: National Prisoner Statistics series, originally published by the Bureau of the Census and later by the Bureau of Prisons and the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, and now published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. The 1923 report is available here. Reports for the years 1926-1935 are available here, 1948-1970 here, and 1971-1973 here. Reports for 1936-46, and 1974-1978 were located in the Five College Library Repository Collection, at “the Bunker”. Full sourcing details for each year are available in Table 3.

- 1978 to 2015: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) — Prisoners showing the yearend jurisdictional population in “State Institutions (Total)” that has a sentence of greater than one year, by sex

A few notes on the prison data: Wherever possible, the reported December 31 estimates were used, for consistency with later datasets. When no December estimate was given, the January 1 estimate of the following year was used. Also, because estimates are often updated after initial publication, we used data from the more recent available source. For 1937 and 1939-1943, the total state and federal prison populations by sex were not reported. However, for 1937 and 1939, only one federal prison was reported to hold women and only women (in Alderson, West Virginia). For those two years, the federal prison population for women is available, reported as the yearend population of that one prison. Finally, while estimates for most years do not differentiate by status, as of 1971 estimates of the population sentenced to greater than 1 year became standard, and we use that population from 1971 forward to be consistent with the state-level data used elsewhere in the report.

The local jail data was compiled from the following sources:

- 1922: Bureau of the Census, Prisoners 1923: Crime conditions in the United States as reflected in Census statistics of imprisoned offenders.

- 1933 to 1981: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Historical Corrections Statistics in the United States, 1850 – 1984, Table 4-15 provides the total jail population and the percentage of the jail population that is female for selected years. We then calculated estimates by sex using these percentages. Note that for 1970 (for which two different estimates are given), we used the estimate from the National Jail Census.

- 1982: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates 1982, Table 2 (total of adult and juvenile females).

- 1983 to 1989: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Criminal Justice Sourcebook (1993), Table 6.17.

- 1990 to 2015: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear series. Full sourcing details for each year are available in Table 3.

We calculated the national incarceration rates for state prisons, federal prisons, and local jails using the numbers above and population estimates from the Census Bureau. Because the state and federal prison data is for the last day of the reported year, we used population estimates for January 1 of the next year for prison incarceration rates. The Census Bureau publishes population estimates as of July 1 of each year back to 1900, and for January 1 for selected years (1981-2000, and 2011 to 2016). Where possible, we used the Census Bureau’s January 1 figures, and for the others, we used the July 1 estimates to produce our own estimates for each January.

Because the jail data for 1982-2015 was based on counts as of June 30, we used the Census Bureau’s estimates for July 1 of each year for jail incarceration rates for those years. Because it was not immediately clear to us when jails data for the previous years were collected, we used the January 1 estimates for the earlier years.

The U.S. female resident population data was compiled from:

- 1922 to 1979: National Intercensal Tables 1900-1990

- 1980 to 1989: National Intercensal Datasets: 1980-1990, Quarterly Intercensal Residential Population Estimates. January 1 estimates were reported by the Census, except for 1980, which was calculated by averaging the July 1979 and July 1980 estimates.

- 1990 to 2000: National Intercensal Datasets: 1990-2000, Intercensal Estimates of the United States Resident Population by Age and sex, 1990-2000: Selected Months.

- 2001 to 2010: National Intercensal Datasets: 2000-2010, Intercensal Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin

- 2011 to 2016: Monthly National Population by Characteristics 2010-2017 Datasets, Monthly Postcensal Resident Population.

The graph “Women’s state prison populations have grown faster than men’s” (Figure 2) charts the multiple by which the women’s and men’s state prison populations nationwide changed from 1978 to each given year. This was calculated by finding the percent change from 1978 to each year, then adding 1 to find the multiple. For example, a 300% (3.0) change meant the population grew 4 times larger. The data underlying this graph is from Bureau of Justice Statistics, Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) — Prisoners showing the yearend jurisdictional population in “State Institutions (Total)” with sentences of greater than one year, by sex.

The graph “Women’s prison incarceration rate in select states and all 50 States” (Figure 3) uses data from these sources:

- 50 state prison population incarceration rate 1922-2015: See the sourcing information for “State policy drives women’s incarceration growth” (Figure 1) above.

- State prison incarceration rates for Oklahoma, Arizona, California, and Maine, 1978-2015: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) — Prisoners showing the yearend imprisonment rates of jurisdictional populations with sentences greater than one year for each state, by sex.

Using 2009 as a reference point:

Throughout this report, we use 2009 as a consistent reference point when comparing women’s and men’s recent incarceration trends. This choice was made for comparison purposes; 2009 was the year of the national total (combined men’s and women’s populations) peak of state prison populations. Because the national peak population for women in state prisons occurred in 2008, a year earlier than the peak for men, this choice underreports declines for women in some states and nationally. However, this choice is more useful for comparison to the more dramatic changes that have occurred in the men’s population since 2009.

When the change in women’s populations is measured from 2008 to 2015 (instead of 2009), women still fare worse in 35 states, but the breakdown of the differences between men and women is different: in 11 states, women’s populations increase while men’s decrease; in 21 states, women’s populations increase more dramatically (in terms of percent change) than men’s populations; and in 3 states, women’s populations decline less dramatically than men’s populations. In 13 states, men’s state prison populations fare worse than women’s populations, and in 2 states, both men and women’s populations decline proportionally.

Inclusion of states with combined jail and prison systems

Six states — Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont — have combined prison and jail systems. But because the data used in this report is based on state jurisdictional populations with sentences greater than one year, the incarcerated people in these six states who would (in other states) likely be under the authority of local jails (such as those awaiting trial or serving short sentences of less than a year) are excluded from this data.

Offense data sources:

In the sidebar “Context: What’s behind women’s prison growth?”, the discussion of drug- and violent offenses as drivers of women’s incarceration draws from several data sources. Gender-specific data on most serious offenses is only publicly available for selected years until 2000, at which point yearly data is available in the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) yearly “Prisoners” series of reports. Before 2000, this data is available (by percentages) for 1979, 1986, 1991, and 1997 on page 14 of the 1999 BJS report “Women Offenders”. We calculated the number of women incarcerated for each offense category using these percentages and the estimates reported by the BJS Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) – Prisoners for yearend jurisdictional population with sentences greater than one year for total state institutions, by sex. To determine how much of the population change over a given period of time was due to each offense category, we divided the change in the population within each category by the total change in the population during that period.

Appendices

- Table 1. Women's prison and jail population estimates and incarceration rates, 1922-2015

- Table 2. Changes in state prison populations since 2009, by sex

- Table 3. Sources for population estimates by sex, 1922-2015

Acknowledgements

This report was supported by a generous grant from the Public Welfare Foundation and by the individual donors who support the Prison Policy Initiative’s ongoing research and advocacy work.

The author wishes to thank her Prison Policy Initiative colleagues Wanda Bertram, Lucius Couloute, Aleks Kajstura, and Peter Wagner for their feedback and assistance in the drafting of this report. Joshua Aiken, Elliot Oberholtzer, and Ida Hay of the Five College Library Depository provided research assistance on the historical data on women’s incarceration prior to 1978. Jordan Miner facilitated the production of the individual state graphs, and Bob Machuga created the cover.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is most well-known for its big-picture publication Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie that helps the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform. This report builds upon the organization’s 2014 analysis of state prison growth, Tracking State Prison Growth in 50 States and its 2015 report States of Women’s Incarceration: The Global Context, which shows that women’s incarceration rates in each state are higher than those of most other nations, as well as its analysis of women’s incarceration in 2017, Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie.

About the author

Wendy Sawyer is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. She is the author of Punishing Poverty: The high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts, a report showing that probation fees hit the state’s poor communities hardest.

Footnotes

From 2000-2015, the women’s jail population grew 40%, while the number of women in state prisons nationwide grew 22%. Meanwhile, over the same period, the total jail population (including both men and women, but comprised of mostly men) grew 17%, and the total state prison population grew 7%. For analysis specifically about the growth of women’s incarceration in jails, see The Vera Institute of Justice’s report, Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform. ↩

For more on the problems leading to – and caused by – the jailing of women, see the Vera Institute of Justice’s report Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform. ↩

In 1978, men made up 96.3% of state prison populations, and in 2015, they made up 92.8%. ↩

The men’s state prison population nationwide grew 367% from 1978 to 2015. (Both men’s and women’s state prison population growth far outpaced the growth of the total U.S. population, which grew by 44% over the same period.) Comparing growth of different groups based on percent change can be problematic, of course, because the baseline 1978 prison populations used for these calculations are so different for men and women. For this report, the comparison with the percent change in the men’s population is only to provide a reference point for the focus of this report: the dramatic growth within women’s prison populations. ↩

While an analysis of racial differences in women’s prison growth is beyond the scope of this report, it’s important to note that prison growth since 1978 has disproportionately impacted women of color, although as the Sentencing Project and Marshall Project have both reported, the “racial dynamics” of women’s incarceration are changing. ↩

From 1979 to 1991, the estimated number of women in state prison whose most serious charge was a drug offense increased from 1,230 to 12,040 – an 879% increase. See methodology for data sources. ↩

See more from Marie Gottschalk and John Pfaff, as well as the Urban Institute’s deep dive into the lengthening of time served. ↩

The question of appropriate responses to violence can be even more complicated for female defendants who have are themselves victims of violence, punished for fighting back against their abusers. A meta-analysis of women’s violence against male partners found that between 64-92% of domestically violent women were also victims. Victoria Law cites a California study that found 93% of women who had killed their partners had been abused by them, and a New York study that found 67% of women incarcerated for killing someone close to them had been abused by their victims. The victimization of women, therefore, is important context for policy decisions related to women’s violent offenses. ↩

National Research Council. (2014). The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Committee on Causes and Consequences of High Rates of Incarceration, J. Travis, B. Western, and S. Redburn, Editors. Committee on Law and Justice, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, p. 346. ↩

Barbara Bloom and Stephanie Covington, Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Women Offenders. In R. Gido and L. Dalley, Eds., Women’s Mental Health Issues Across the Criminal Justice System (Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall, 2008), 160-176 (p. 8-9 of PDF). For more on women’s pathways to incarceration, see John Jay College of Criminal Justice Prisoner Reentry Institute’s report Women InJustice: Gender and the Pathway to Jail in New York City. ↩

Becki Ney, Rachelle Ramirez, and Dr. Marylyn Van Dieten, Eds. Ten Truths That Matter When Working With Justice Involved Women (National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women: 2012), p. 2. ↩

Ney et al., p. 2. See also: Bloom & Covington Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Women Offenders. ↩

The most recent government report (based on 2011-2012 data) found that two-thirds of women in federal or state prisons report a history of mental health problems. It did not address co-occurring disorders or histories of abuse. ↩

An Urban Institute study found that 14% of women with substance use disorders participated in “formal treatment programs” (i.e. therapeutic communities and pharmaceutical treatment regiments) in prison, compared with 29% of men. The total treatment rate for women for substance use disorders, including participation in groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, was about 41%. (See p. 11-12 of that report.) An earlier Bureau of Justice Statistics report found that 20% of “alcohol- or drug-involved” women received treatment for substance use disorders in state prisons (see table 14). (The most recent BJS report on treatment for substance use disorders does not report men and women’s treatment rates separately. However, it shows that about 29% of all state prisoners participate in any drug treatment program, including self-help groups.) ↩

Bloom & Covington, p. 7-8. ↩

Six states – Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont – have combined prison and jail systems, and therefore only report state prison data. Because the data used in this report is based on state jurisdictional populations with sentences greater than one year, most incarcerated people in these six states who would otherwise be under the authority of local jails (such as those awaiting trial or serving short sentences of less than a year) are excluded from this data. ↩

The Sentencing Project offers further, detailed analysis of individual state-level sentencing policy changes. See Fewer Prisoners, Less Crime: A Tale of Three States, and for changes that may have impacted women more directly, The Changing Racial Dynamics of Women’s Incarceration. ↩

In 2015, there were 67,529 fewer people in state prisons nationwide than in 2009. Of those, only 195 were women. Moreover, while total state prison incarceration rates are slowly falling too, women’s rates have fallen less dramatically than men’s rates since 2007. Between 2007 (when rates for both men and women peaked) and 2015, men’s state prison incarceration rates fell by 10%, while women’s rates fell by 6.5%. ↩

For comparison purposes in this 50-state survey, this report uses the 2009 national total peak of state prison populations as a consistent reference point. See methodology for explanation. ↩

In one state – Colorado – women’s and men’s state prison populations have both declined by about the same amount (12%). ↩

The Sentencing Project discussed this possibility in The Changing Racial Dynamics of Women’s Incarceration (see p. 9). That report uses as an example changes in to the life expectancy of white women with less than a high school education (which fell more than 5 years from 1990 to 2008), which was likely related to a number of socioeconomic factors that are also associated with criminal justice involvement. ↩

Disciplinary responses are also more severe for women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders; see: K. Houser & S. Belenko, Disciplinary responses to misconduct among female prison inmates with mental illness, substance use disorders, and co-occurring disorders (2015). Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 83(1), p. 23-34. ↩

For more on abuse by correctional staff, see Amnesty International’s report Women In Custody, Kim Shayo Buchanan’s article Impunity: Sexual Abuse in Women’s Prisons in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, and the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division’s investigation of the Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women. ↩

One in five (20%) of transgender survey respondents who were incarcerated in jail, prison, or juvenile detention in the past year reported that they had been assaulted by facility staff or other incarcerated individuals: See p. 191 of The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. ↩

4% of women are pregnant upon admission to state prisons, yet only about half receive pregnancy care, according to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report. In These Times details the health risks to pregnant and postpartum incarcerated women and their children. And as reported in The Atlantic, women who give birth in prison are usually separated from their babies shortly after delivery, their care transferred to family, friends, or the foster care system. ↩

According to a 2010 Bureau of Justice Statistics report, “More than 4 in 10 mothers in state prison who had minor children were living in single-parent households in the month before arrest.” Before incarceration, over half of mothers in state prisons lived with their children and over half provided primary financial support for their children. And “[a]mong parents in state prison who provided the primary financial support to their children, mothers (89%) were more likely than fathers (67%) to report that they had lived with their children.” (See pages 3-5.) For more information on how parental incarceration affects children, families, and communities, see the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s report, A Shared Sentence. ↩

Before incarceration, women in prison earned 29% less than incarcerated men, and 42% less than non-incarcerated women. See the Prison Policy Initiative’s report Prisons of Poverty for an analysis of pre-incarceration incomes of people in prison, and Detaining the Poor for an analysis of the incomes of people who were detained because they can’t afford to pay bail. ↩

According to the Sentencing Project, only half of women in prison participate in educational or vocational programming; one in five takes high school or GED classes, and less than one in three participates in a vocational program. ↩

Bloom & Covington, p. 26. ↩

In 2006, a Gender Responsive Strategies Commission, created to advise the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation on correctional strategies specific to women, proposed the construction of additional prison beds to move 4,500 women deemed suitable for release from state prisons to smaller facilities closer to home – instead of simply releasing them. See an analysis by Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB). ↩

Some diversion programs are unaffordable for poor defendants; as much as possible, program costs for participants should be eliminated, minimized, or deferred. See Shaila Dewan and Andrew W. Lehren’s New York Times investigation, “After a Crime, the Price of a Second Chance”. ↩

For a state-by state list of current and past problem-solving court projects, see the National Center for State Courts website. ↩

For detailed descriptions of different prosecutor-led diversion programs, their results, costs, and related resources, see Fair and Just Prosecution’s Issues at a Glance: Promising Practices in Prosecutor-Led Diversion. ↩

For more information, see p. 3 of the Prison Policy Initiative’s Winnable criminal justice reforms (2017). ↩

For more information, see p. 2 of the Prison Policy Initiative’s Winnable criminal justice reforms (2017). ↩

An Urban Institute study found that, upon reentry, women experience more housing instability, have lower rates of employment, receive less financial support from family, and report more criminal involvement than men. ↩

For more information see the National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women’s Reentry Considerations for Justice-Involved Women and Patricia Van Voorhis, Women’s risk factors and new treatments/interventions for addressing them: Evidence-based interventions in the United States and Canada (2012). United Nations Asia and Far East Institute, Resource Materials Series No. 90. ↩

For more information on collateral consequences, see the National Inventory of the Collateral Consequences of Conviction, The Collateral Consequences Resource Center, and the Sentencing Project. For information about driver’s license suspensions for offenses unrelated to driving, see the Prison Policy Initiative’s related work. ↩

For more information on criminal justice debt, see the 50-State Criminal Justice Debt Reform Builder by the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School and the program’s related report Confronting Criminal Justice Debt: A Guide For Policy Reform. ↩

Events

- April 30, 2025:

On Wednesday, April 30th, at noon Eastern, Communications Strategist Wanda Bertram will take part in a panel discussion with The Center for Just Journalism on the 100th day of the second Trump administration. They’ll discuss the impacts the administration has had on criminal legal policy and issues that have flown under the radar. Register here.

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.