Arguments against jail expansion

- Sections

- Four key findings about jail overcrowding

- Counterarguments to the rhetoric of jail expansionists

- Points of intervention in jail fights

The reflexive response to jail overcrowding is often to build a larger jail. The research is clear: building more jail cells is never likely to be a good solution to overcrowding for anyone except the law enforcement agencies and jail architects who have a financial interest in building more jails.

Since 2015, the Prison Policy Initiative has gathered data to produce reports about the harms jails cause communities and the alternatives to incarceration that make communities safer for everyone. Below, we’ve organized these resources to support advocates with the data that empowers communities and educates local decision makers.

If you have questions or we can be of more assistance, please contact us.

Four key findings about jail overcrowding

Pretrial detention drives jail population growth. Counties can reduce overcrowding by reforming money bail.

On a structural level, money bail contributes to jail overcrowding. On a human level, it unfairly penalizes poor people. Our report “Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time” analyzes the pre-incarceration incomes of people who are in jail to show that the money bail system makes it impossible for many incarcerated people to pay bail.

- Over 65 percent of people in local jails are being held pretrial.

- In 2015, the median felony bail bond amount was $10,000 in the United States. This represented eight months of income for the typical detained defendant, who had a median annual income of $15,109.

The driving factor in jail growth is not increases in crime; it is policy changes that make it more likely for people to be detained prior to trial.

Law enforcement often claims pretrial reform puts community safety at risk. We put these claims to the test in “Releasing people pretrial doesn’t harm public safety,” where we saw decreases or negligible increases in crime in twelve of thirteen jurisdictions after pretrial reforms.

- The New Jersey legislature virtually eliminated cash bail in 2017. Between 2015 and 2018, the pretrial population decreased by almost half (44%), while the crime rate fell by about 15%

- In New Orleans, Louisiana bail reform resulted in a 337 percent increase in the number of people released without bail from 2009 to 2019. A subsequent crime analysis found that defendants released without paying bail were no more likely to be arrested than those who paid bail.

Most people in jail pose little threat to public safety. Counties can resolve overcrowding by taking a public health approach to low-level offenses rather than a punitive approach.

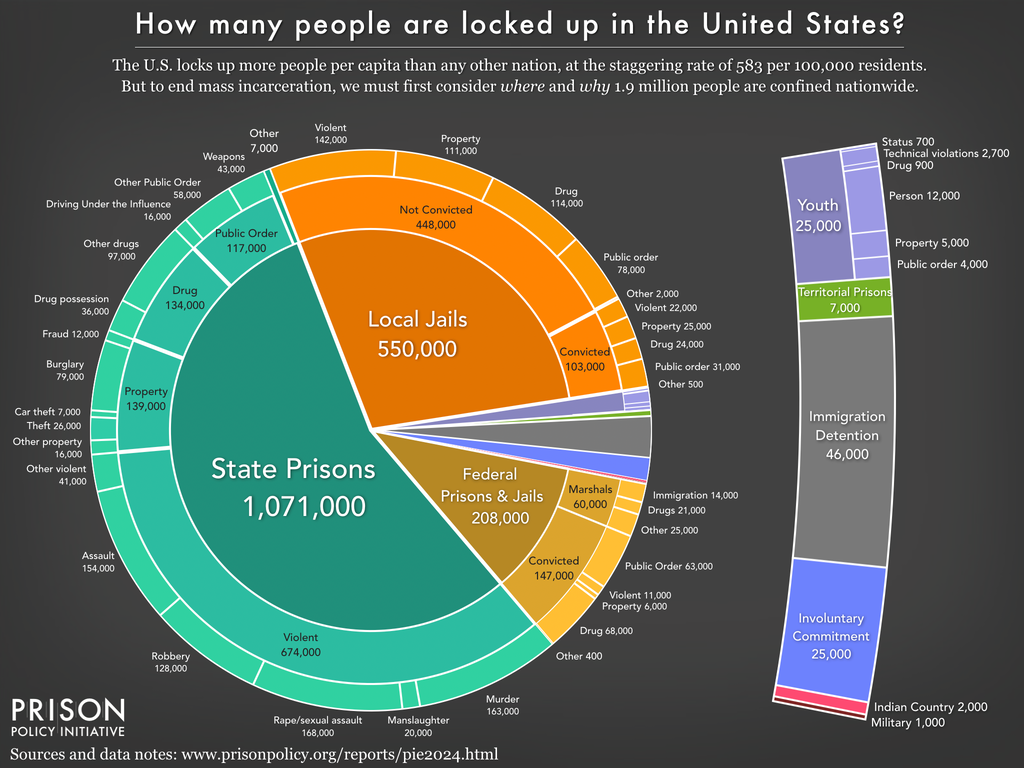

Check out our Whole Pie report for a broad picture of incarceration in the United States.

“Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2024” provides a big picture explainer that compiles the national data about who is incarcerated, where, and on what grounds. It includes helpful infographics that capture jail population composition and pretrial status in a glance.

- More than three-quarters of people in jail who have been convicted are incarcerated for public order offenses, property crimes, and drug-related offenses.

- Misdemeanors account for over 25 percent of daily jail populations nationally.

Use the map above to get a state-specific breakdown of the number of people incarcerated in jails and jail trends over time.

“Arrest, Release, Repeat: How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems” shows how substance abuse disorders and mental health problems are the underlying factors that cause many people to cycle in and out of jail.

- Over half of people arrested multiple times within a year reported a substance use disorder in the past year.

- People with multiple arrests are three times more likely to have a serious mental illness and three times more likely to report serious psychological distress than people with no arrests in the past year.

Probation and parole violations — which are not crimes — comprise over one-third of some jail populations. Counties can reduce jail overcrowding by reforming their probation and parole practices.

“Technical violations, immigration detainers, and other bad reasons to keep people in jail” explains how detainers contribute unnecessarily to jailing. Detainers, or “holds,” are administrative requests that a person be held in jail, and they’re frequently issued to hold people on probation or parole in jail pending the disposition of a probation or parole revocation decision.

- In 2002 (the most recent year for which we have national data), 20 percent of the jail population nationwide - including 44 percent of the pretrial population - were under community supervision.

- A review of jail population data from 30 rural counties revealed that charges related to supervision violations account for an average of 14.6 percent of all charges against people held in jail.

“Technical difficulties: D.C. data shows how minor supervision violations contribute to excessive jailing” uses data about Washington, D.C. jails to explore excessive jail detention for technical violations, including the behaviors that lead to violations and the lengths of time people can be held for violations. The brief illustrates how probation and parole systems set people up to fail.

- The Washington, D.C. Department of Corrections estimates that 14.3 percent of all men and 8.5 percent of all women housed in the system are held as a result of a parole violation.

- In 2020, parole violations accounted for the second and third most common “most serious offense” that resulted in men and women, respectively, being incarcerated in D.C. jails.

- The average length of stay in a D.C. jail for a parole violation is four months. That’s almost four times as long as people awaiting trial for misdemeanors stay in jail.

The 2020 response to the COVID-19 pandemic showed us that we can reduce jail populations when we want to.

Reducing the number of people held pretrial, reforming probation and parole practices, and adopting a public health approach to low-level offenses have proven safe measures that decrease the need for jail expansion. Counties’ initial responses to COVID-19 demonstrated as much. Although many of these counties reversed their reforms as public outcries over COVID subsided, the temporary policies still serve as concrete evidence that jail population reduction is often not a question of know-how or public safety. It’s a matter of political will.

“New data on jail populations: The good, the bad, and the ugly” is a retrospective on jail practices in response to COVID-19. Data shows that policy responses to the pandemic reduced jail populations by as much as 25%.

- In the one-year period ending June 30, 2020, there were 1.67 million fewer jail admissions compared to the previous year.

- Of those booked into jails between March 1 and June 30, 2020, 208,500 received an expedited release in response to COVID-19.

- Early in the pandemic, many police departments were encouraged to use arrest as “a tool of last resort,” reducing stops, and shifting to citations in lieu of arrest. As a result, the number of people held for misdemeanors dropped by 45 percent and the number of people held pretrial dropped by 21 percent.

“The most significant criminal justice policy changes from the COVID-19 pandemic” is a policy tracker that provides examples of what steps legislators, governors, courts, prosecutors, and corrections departments took to reduce jail (and prison) populations in 2020.

- In Washington County, Oregon, the sheriff reduced the jail population by half through early releases of people held for “low-level offenses.”

- In April, district attorneys worked with jails in Pennsylvania, using their prosecutorial discretion, to reduce the jail population by 30 percent.

- In Kentucky, police departments instituted citations in lieu of arrests for minor offenses to reduce the pretrial jail population.

- In Cuyahoga County, the sheriff announced that the jail would stop admitting people on new misdemeanor charges, except in cases of domestic violence charges, to reduce the jail population in the face of growing COVID-19 infection rates.

Counterarguments to the rhetoric of jail expansionists

Below, we’ve paired three common arguments jail proponents make with the counterarguments advocates have successfully used to stop jail expansion projects. We’ve published many reports that support advocates’ rebuttals, so we’ve included report summaries and, in some cases, key findings after each counterargument.

Argument“Our jail is overcrowded, and overcrowding makes staff and incarcerated people unsafe.”

First counterargument Multiple practices and policies can be adopted to reduce jail populations and the need to create more jail capacity.

“Does our county really need a bigger jail? A guide for avoiding unnecessary jail expansion” is a roadmap to alternatives, like diversion programs, to overcrowding. This report encourages counties to consider the ways they can decrease their jail population by reducing the number of people detained pretrial, reducing the number of people who are incarcerated with substance abuse problems or for low-level offenses, and eliminating the practice of renting beds to other authorities.

- Nationally, 68 percent of the jail population meets medical standards for having a diagnosable substance abuse disorder. These individuals would be better served by community-based health and social services.

- Most people in jail pose little or no threat to public safety as they have been convicted or are incarcerated for property, drug, or public order offenses.

- As of 2013, 84 percent of jails were renting jail space to other agencies. These beds represent spaces that could be used to reduce overcrowding of the jail population under local authority.

“Smoke and mirrors: A cautionary tale for counties considering a big, costly new jail” provides a case study of what can happen when counties fail to ask the right questions about overcrowding and public safety. It points out some common mistakes jail architects make when conducting a jail assessment:

- Future jail population projections should not be based primarily on projected population growth; instead, they should be based on the capacity needs as determined after an assessment of the local justice process as a whole.

- Similarly, the jail assessment’s projections of future jail needs should account for the anticipated effects of recent legislative changes (such as decriminalization of cannabis, pretrial reforms, changes to sentencing guidelines, etc.)

Another counterargument Building a larger or new jail in response to overcrowding often has a perverse effect and results in higher levels of incarceration.

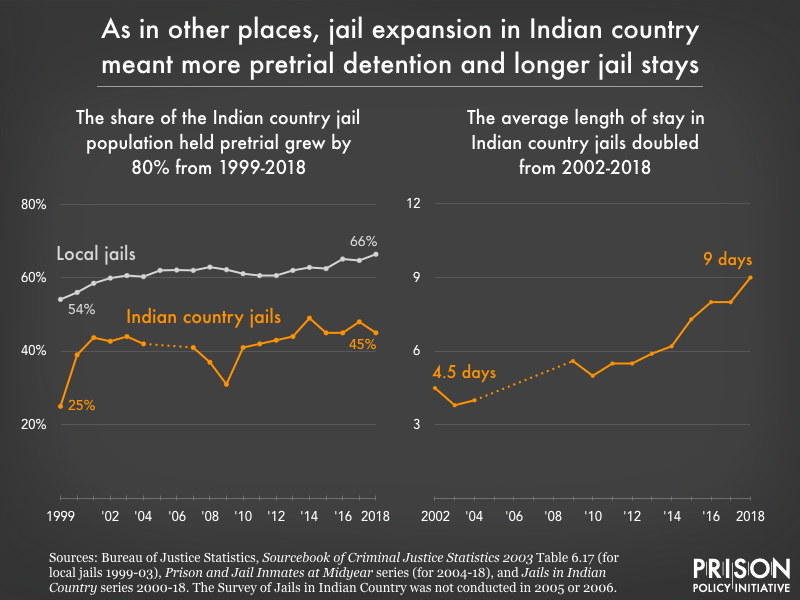

“New BJS data reveals a jail-building boom in Indian country” examines how jail construction over eighteen years on Native American reservations in response to overcrowding resulted in more pretrial detention, higher incarceration rates, and more overcrowded facilities.

- The number of jails in tribal lands grew from 68 in 2000 to 84 in 2018, and 35 percent of jails on tribal lands are still holding more people than they were designed to hold.

- In the same time period, the number of people in jails on tribal lands has grown by about 60 percent even though the total number of people living in these areas has hardly changed.

- For 16 percent of people in these jails, the most serious charge on which they are held is “public intoxication.”

“Broken Ground: Why America Keeps Building More Jails and What It Can Do Instead” is a report from the Vera Institute for Justice that examines how investing in jail expansion can virtually guarantee the need for continued jail expansion.

- A bright line example of this phenomena: in 2000, Salt Lake County built a 2,000-bed jail to replace an 870-bed jail. The new jail filled to capacity within 21 days of opening.

Argument 2 ”We need to increase our jail size to provide better medical services to our mentally ill population.”

Counterargument:Jails should never be the response to mental health concerns. Even a few days in jail can be especially devastating for people with serious mental health and medical needs. Research suggests that people with mental health and substance abuse needs are better served with social services in their communities, not in jails.

“The ‘services’ offered by jails don’t make them safe places for vulnerable people” is a short article that summarizes how harmful jail “health services” tend to be.

- Although two-thirds of people in jails have substance abuse issues, most jails refuse to provide medication assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder—the gold standard for care.

- Studies in several states have found that people released from incarceration are up to 120 times more likely to die of overdose than the general population.

“Arrest, Release, Repeat: How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems” includes links to articles and studies that show the dangers of counties investing in jails as mental health providers and the benefit of investing in community-based mental health care.

- History has shown that jails are unable to provide effective mental health and medical care.

- Jailing people with serious mental illness and substance abuse disorders has lethal consequences.

- Investing in community-based mental health care and treatment for substance use disorders yields a $12 return for every $1 spent.

Argument 3”We need to build a modern, more humane jail to close an old jail with terrible living conditions.”

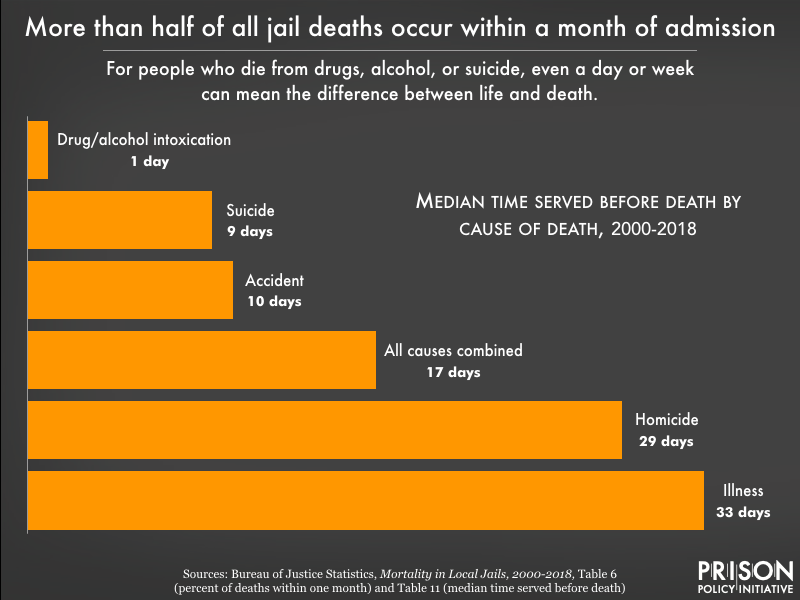

Counterargument:All jails have terrible living conditions and technology has not changed that. The U.S. has been on a jail construction boom for almost forty years, building “modern” jails and expanding old jails. Deaths in jails have only gone up. If proponents are looking for humane solutions to terrible living conditions, the data points away from jail expansion. Research suggests that jail incarceration drives deaths.

“Rise in jail deaths is especially troubling as jail populations become more rural and more female” analyzes Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) mortality data, showing that jails are increasingly unsafe places to be for even a few days.

- 2018 BJS data shows the highest death rate since BJS’ first report on mortality in jails in 2000.

- Someone in jail is more than three times as likely to die from suicide as someone in the general U.S. population.

- Women made up one-sixth of all jail deaths in 2018, and they have a higher mortality rate than men in jails.

- Small jails-particularly those with an average daily population of 49 or fewer -reported the highest mortality rates in 2018.

Points of intervention in jail fights

Advocates can choose from several opportunities to intervene to stop jail expansions:

- County decision makers and ballot measures. Jail construction projects are often approved by local officeholders or by county voters via a ballot initiative. Advocates can engage at commission meetings or campaign against ballot initiatives.

- State legislature. Sometimes state legislatures pass measures to aid and advance jail expansion in their state. Such has been the case in both Massachusetts and California. In such cases advocates can engage with their representatives, relevant committee members, and relevant committees to voice their concerns with the legislation.

- Procedure. Groups have mobilized when counties fail to follow necessary procedures for a jail construction project, resulting in the halting of jail projects. For example: Families for Justice as Healing halted a $50 million jail expansion project in Massachusetts because the panel examining the impact of the expansion wasn’t given proper notice of a Request for Proposal (RFP). In California, advocates stopped the construction of a new jail by debunking the environmental impact report that supported jail expansion.

- Bad data. Counties often commission analyses to show the need for a larger jail. These "jail assessments" can be full of faulty logic, such as misleading projections of jail populations, which advocates can raise up to the public. For more information, see our how-to guide for reading jail assessments critically.

- Budget. Jail expansion cannot happen if the decision makers in charge of the county’s money do not sign off on the project. The Vera Institute of Justice’s What Jails Cost Cities page provides a look at 47 county jail budgets and shows how decreasing jail populations translates to budget savings.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.