Arrest, Release, Repeat:

How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems

By Alexi Jones and Wendy Sawyer

August 2019

Press release

In November 2024, we released a briefing with updated data on repeat jail bookings. We recommend checking that out as well.

Police and jails are supposed to promote public safety. Increasingly, however, law enforcement is called upon to respond punitively to medical and economic problems unrelated to public safety issues. As a result, local jails are filled with people who need medical care and social services, many of whom cycle in and out of jail without ever receiving the help they need. Conversations about this problem are becoming more frequent, but until now, these conversations have been missing three fundamental data points: how many people go to jail each year, how many return, and which underlying problems fuel this cycle.

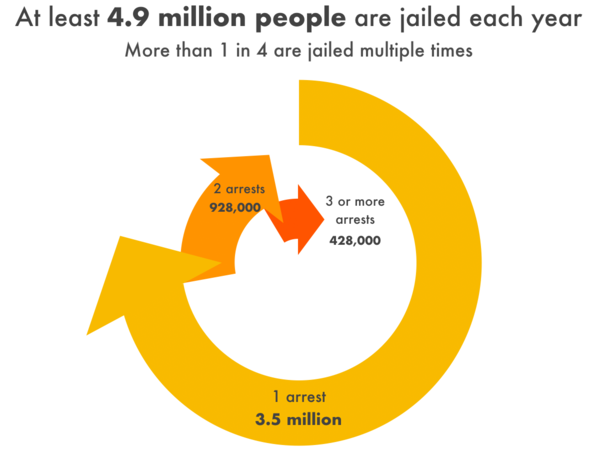

In this report, we fill this troubling data gap with a new analysis of a federal survey, finding that at least 4.9 million people are arrested and jailed each year,1 and at least one in 4 of those individuals are booked into jail more than once during the same year.2 Our analysis shows that repeated arrests are related to race and poverty, as well as high rates of mental illness and substance use disorders. Ultimately, we find that people who are jailed have much higher rates of social, economic, and health problems that cannot and should not be addressed through incarceration.

Fortunately, as we discuss in our recommendations, there are policy solutions that can break this cycle of incarceration by addressing people’s needs in their communities rather than through the criminal justice system.

By the numbers: At least 4.9 million individuals are arrested and booked per year

Using nationally representative data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), we find that at least 4.9 million individuals were arrested and booked in 20173. Of those 4.9 million individuals, 3.5 million were arrested only once in 2017; 930,000 were arrested twice; and 430,000 were arrested three or more times.

People with multiple arrests disproportionately come from marginalized populations

Most broadly, we find important demographic differences between people with multiple arrests in the past year and those with no arrests or just one arrest. Our analysis shows that people with multiple arrests are disproportionately: Black, low-income, less educated, and unemployed. Moreover, the vast majority are arrested for non-violent offenses. This suggests that instead of incarceration, which diminishes economic prospects, public investments in employment assistance, education and vocational training, and financial assistance would help mediate the conditions that lead marginalized individuals to police contact in the first place.

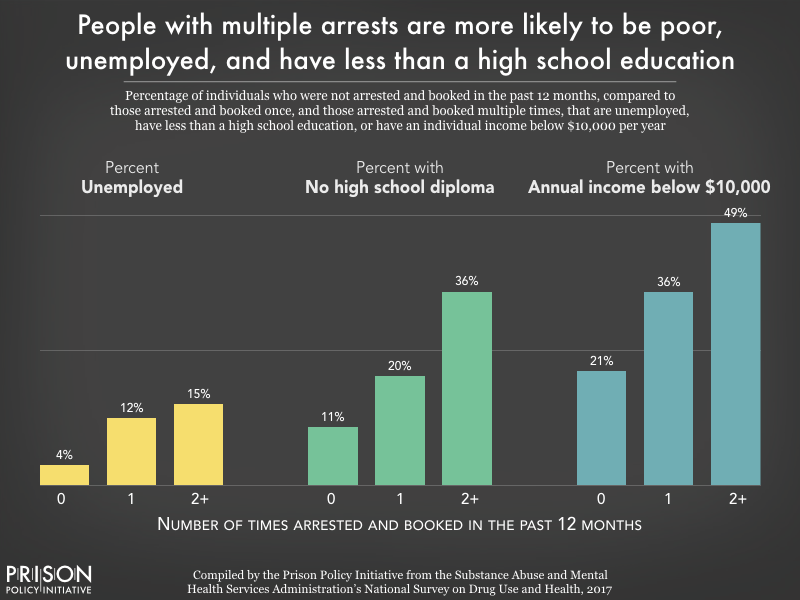

Specifically, we find that:

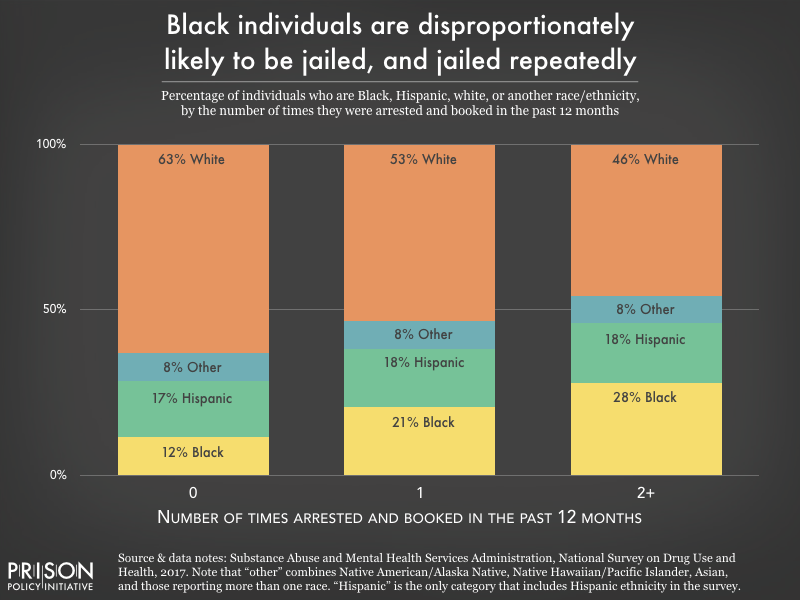

- Black Americans are overrepresented among people who were arrested in 2017. Despite making up only 13% of the general population, Black men and women account for 21% of people who were arrested just once and 28% of people arrested multiple times in 2017. This is partly reflective of persistent residential segregation and racial profiling, which subject Black individuals and communities to greater surveillance and increased likelihood of police stops and searches.

- Poverty is strongly correlated with multiple arrests. Nearly half (49%) of people with multiple arrests in the past year had individual incomes below $10,000 per year. In contrast, about a third (36%) of people arrested only once, and only one in five (21%) people who had no arrests, had incomes below $10,000.

- Low educational attainment increases the likelihood of arrest, especially multiple arrests. Two-thirds (66%) of people with multiple arrests had no more than a high school education, compared to half (51%) of those who were arrested once and a third (33%) of people who had no arrests in the past year.5

- People with multiple arrests are 4 times more likely to be unemployed (15%) than those with no arrests in the past year (4%).

- Most people arrested multiple times don’t pose a serious public safety risk. The vast majority (88%) of people who were arrested and jailed multiple times had not been arrested for a serious violent offense in the past year.6

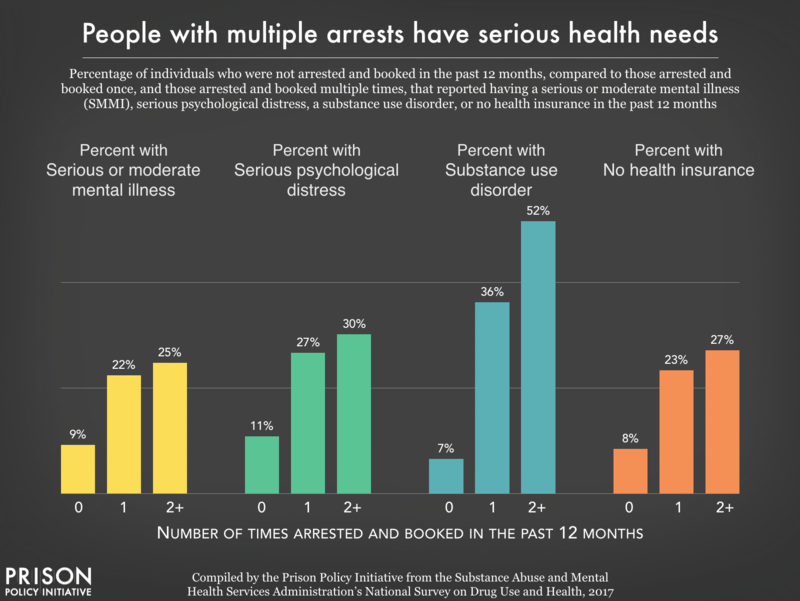

People with multiple arrests have greater health needs

In addition to social and economic factors, our analysis also shows that people who are arrested and booked more than once per year often have underlying health issues, many of which can lead to police contact. Our finding that people with multiple arrests have low rates of violence but serious medical and mental health needs gives new urgency to the growing concerns that jails have become “the de facto mental health care system in many communities,” and that police are often used to respond to medical and mental health problems, not to matters of public safety.

Our analysis demonstrates that a significant portion of people with multiple arrests have serious mental health and medical needs that cannot and should not be addressed by jails:

- Over half (52%) of people arrested multiple times reported a substance use disorder in the past year.7 In contrast, 36% of people arrested once and just 7% of people who were not arrested had a substance use disorder in the past year.

- People with multiple arrests were 3 times more likely to have a serious mental illness (25% vs. 9%) and 3 times more likely to report serious psychological distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety, than people with no arrests in the past year (30% vs 11%).

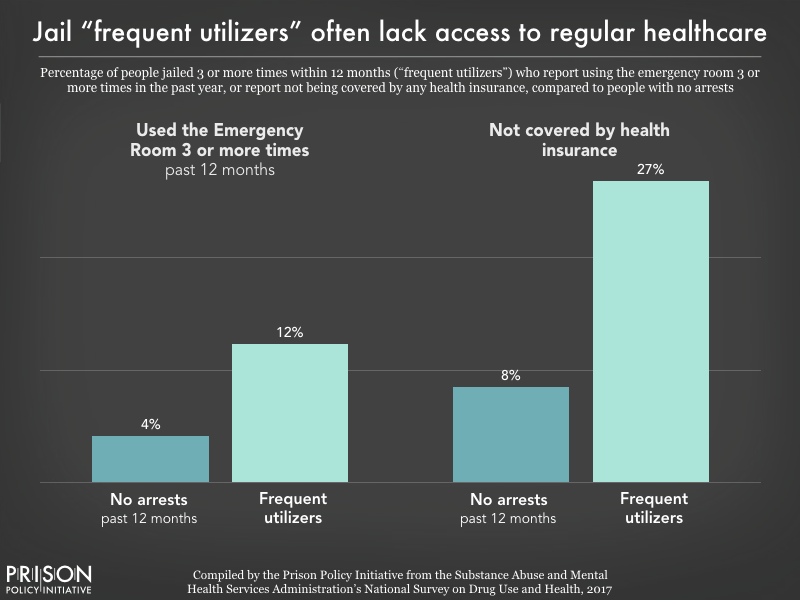

- People with multiple arrests were less likely to have access to health care. Individuals who were arrested and booked more than once were over 3 times more likely to have no health insurance (27%) compared to those with no arrests in the past year (8%), and slightly more likely to lack insurance than people arrested just once (23%).

- HIV prevalence was 11 times higher among people with multiple arrests (1.68%) compared to people with no arrests in the past year (0.15%). There is a significant overlap between social determinants of HIV and risk factors for incarceration; for example, intravenous drug use, homelessness, and poverty all increase the risk of both HIV and incarceration. Moreover, incarceration can be especially dangerous for people living with HIV, as many jails fail to provide appropriate HIV care.

Even a few days in jail can be especially devastating for people with serious mental health and medical needs, as they are cut off from their medications, support systems, and regular healthcare providers. Even worse, many people are in jail in the midst of a health crisis, such as mental distress or substance use withdrawal. Yet history has shown that jails are unable to provide effective mental health and medical care to incarcerated people. Jailing people with serious mental illness and substance use disorders has lethal consequences. Instead, jurisdictions must invest in public health and community-based health services, such as substance use treatment, mental health services, and community health centers, to prevent and treat the underlying issues that can lead to arrest and incarceration.

A closer look at the subset of “frequent utilizers” among those with multiple arrests

The nearly 428,000 people who cycle in and out of jail most frequently (i.e. three or more times over the course of a year) demand special attention in this report and from policymakers. These individuals, sometimes called “frequent utilizers,” repeatedly interact with the criminal justice system and with public services like emergency rooms and emergency shelters.

Although no national data has been published on this phenomenon, several cities have studied how their jails are used and reported that a small portion of people account for a large number of arrests. Unnecessary arrests cost cities and counties millions of dollars but do nothing to fix the underlying medical, economic, and social problems. For example, in New York City, a study of frequent utilizers found that the 800 people with the most arrests accounted for 18,713 jail admissions and $129 million in custody and health costs over five years. In Camden, New Jersey, researchers found that 5% of adults accounted for 25% of all arrests over the five-year study period.

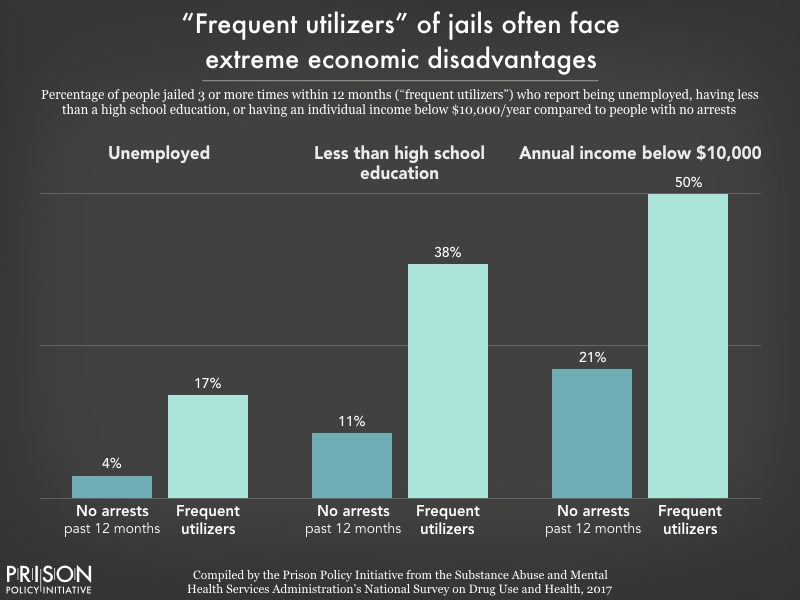

To better provide national data on “frequent utilizers”, we also looked specifically at people who were arrested and booked three or more times in the past year. We found similar, but often more extreme, results compared to the findings discussed above:

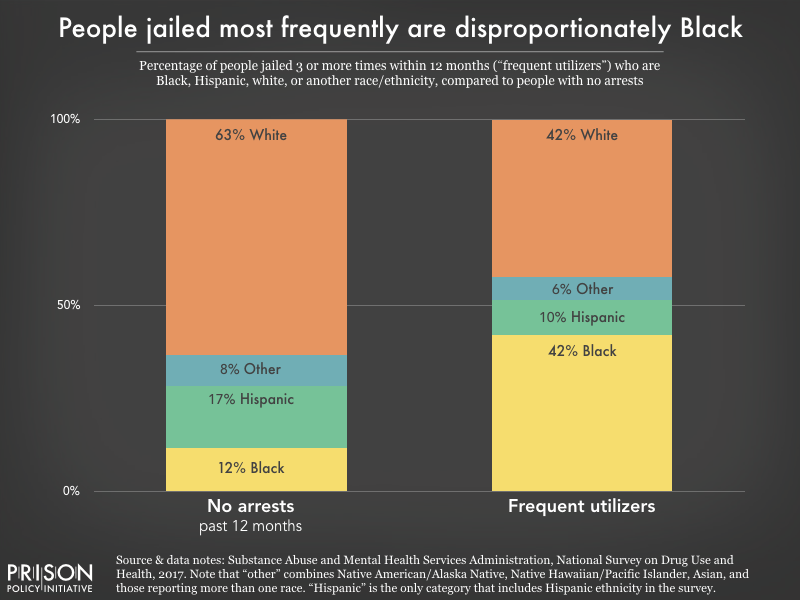

- 42% of people arrested and booked 3 or more times were Black.

- About half (50%) of those most frequently arrested had annual incomes below $10,000 and 85% had incomes below $20,000.

- Educational attainment was lowest among people with 3 or more arrests in a year. Three-quarters (74%) had a high school education or less — with 38% without a high school diploma.

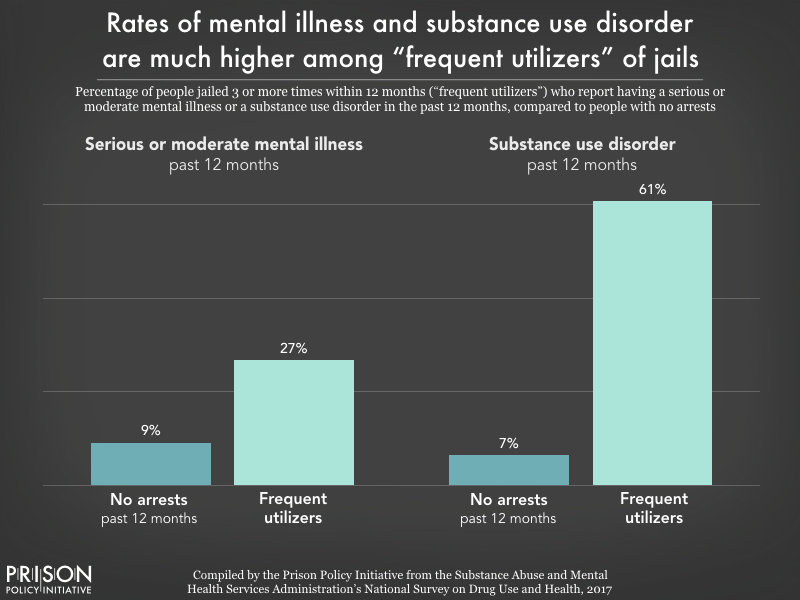

- The majority of people (61%) arrested 3 or more times reported having a substance use disorder. Over a quarter (27%) had a serious or moderate mental illness.

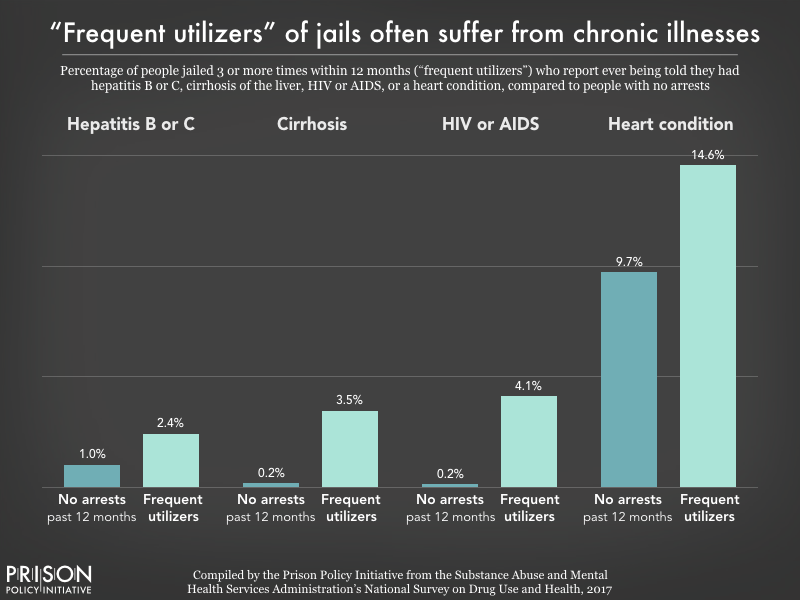

- People with 3 or more arrests were more likely to have been diagnosed with chronic health conditions compared to those with no arrests, including heart conditions (15% vs. 10%), HIV (4.12% vs. 0.15%), cirrhosis (3.47% vs. 0.21%), and hepatitis B or C (2.43% vs. 1.04%).

- Frequent utilizers were more likely to use emergency rooms multiple times in the past year. 36% of frequent utilizers had used the emergency 2 or more times in the past year, compared to 11% of people with no arrests.

Frequent utilizers are characterized by serious public health needs, mental health or substance use disorders, and unstable housing conditions. While interventions specifically targeting frequent utilizers of the criminal justice system are still relatively rare, programs in New York City and Denver have demonstrated that it is possible to stop people from cycling in and out of jail by providing appropriate medical care and social services in the community, including supportive housing, mental health and substance use treatment, and case management. These services, which address the underlying problems that can lead to justice involvement, are more cost-efficient, effective, just, and humane than incarcerating people.

Conclusion

Ultimately, our analysis confirms that people who are repeatedly arrested and jailed are arrested for lower-level offenses, have unmet medical and mental health needs, and are economically marginalized. Arrest and incarceration of these individuals neither enhances public safety nor addresses their underlying needs. Our findings underscore the need to redirect dollars wasted on repeatedly jailing people toward public services that prevent justice involvement in the first place: education, employment assistance, public health, medical and mental health services.

Recommendations

Frequently arresting, jailing and rejailing people who pose little public safety risk has immediate moral and fiscal costs. These costs are compounded as underlying medical, financial, educational, and mental health needs are exacerbated by arrest and detention. To break this cycle, policymakers at the state and local level should:

Redirect taxpayer dollars from jails to expand access to health services:

- Counties should resist jail expansion, close jails when possible, and instead invest in increasing health care capacity. Because of the limited number of psychiatric beds, which are often much further away than jails, law enforcement officers often find it easier to transport people with serious mental illness to jail. The Treatment Advocacy Center estimates it is 2.5 times quicker for law enforcement to transport someone to a jail compared to a medical facility. For example, there are 25 detention sites across Dallas County, Texas, but there are only 3 psychiatric diversion sites for law enforcement. For more on how counties reduce jail populations and invest in community health, see our report Does our county really need a bigger jail? A guide for avoiding unnecessary jail expansion.

- Invest in community-based mental health care and treatment for substance use disorders, which can prevent criminal justice involvement in the first place. Research has demonstrated that access to treatment can reduce both violent and financially motivated crimes in a community. Moreover, investing in such treatment is estimated to yield a $12 return for every $1 spent, as it reduces future crime, costly incarceration, and lowers health care expenses.

- Counties should also provide evidence-based mental health and substance use disorder treatment in jails, including medication-assisted treatment, and connect people with medical care and health insurance upon release to ensure their treatment is not disrupted.

Connect people with social services:

- Expand job training and placement services, educational opportunities, and financial assistance for low-income individuals.

- Expand social services for people with unstable housing, focusing on “Housing First.” This approach acknowledges that stable homes are often necessary before people can address unemployment, illness, substance use disorder, and other problems. “Housing First” reforms, along with expanded social services, would help to disrupt the revolving door of release and reincarceration. Research has found that supportive housing may even pay for itself by reducing people’s use of other public services, such as emergency medical care.

Reduce the number of arrests and jailable offenses:

- Police should issue citations in lieu of arrests, which allow defendants to wait for their court date at home without having to go to jail or post money bail. And local governments should to be sure to link defendants to pretrial services to ensure they make their court date.8

- States should reclassify criminal offenses and turn misdemeanor charges that don’t threaten public safety into non-jailable infractions.

Divert people to other service providers before arrest, and away from jails after arrest:

- States and counties should create pre-arrest diversion programs so people with mental illness and substance use disorders can avoid arrest altogether and be diverted directly to appropriate treatment and services. For example, Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) is a pre-arrest diversion program designed for people for people that engage criminal activity due to unmet behavioral health needs or poverty. Under LEAD, law enforcement diverts peoples who would otherwise be arrested to case managers who respond to the immediate crisis and provide long term intensive case management, including substance use disorder treatment and housing.

- When people with substance use disorders and/or mental illnesses are arrested, states should make treatment-based diversion programs and other harm reduction strategies the default instead of jail. States should ensure their diversion and harm reduction programs are fully funded.9

Evaluate and address the needs frequent utilizers:

- Collect and analyze data in order to identify frequent utilizers and to design interventions. Since frequent utilizers interact with not just the criminal justice system, but also healthcare and homeless services, it is important to integrate data across agencies. This data is crucial to understanding local frequent utilizer populations and designing effective, evidence-based interventions. Interventions should also address racial and ethnic disparities in the frequent utilizer population.

How to link to specific images

To help readers link to specific images in this report, we created these special urls:

- People with multiple arrests are more likely to be poor, unemployed, and have less than a high school education?

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#slideshows/slideshow1/1

- Black individuals are disproportionately likely to be jailed, and jailed repeatedly

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#slideshows/slideshow1/2

- People with multiple arrests have serious health needs

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#healthimage

- “Frequent utilizers” of jails often face extreme economic disadvantages

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#slideshows/slideshow2/1

- People jailed most frequently are disproportionately Black

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#slideshows/slideshow2/2

- Rates of mental illness and substance use disorder are much higher among “frequent utilizers” of jails

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#slideshows/slideshow2/3

- “Frequent utilizers” of jails often suffer from chronic illnesses

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#slideshows/slideshow2/4

- Jail “frequent utilizers” often lack access to regular healthcare

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#slideshows/slideshow2/5

To help readers link to specific report sections or paragraphs, we created these special urls:

- By the numbers: At least 4.9 million individuals are arrested and booked per year

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#bythenumbers

- People with multiple arrests disproportionately come from marginalized populations

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#multiplearrests1

- People with multiple arrests have greater health needs

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#multiplearrests2

- A closer look at the subset of “frequent utilizers” among those with multiple arrests

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#frequentutiliziers

- Recommendations

- /reports/repeatarrests.html#recommendations

A note about using public health data for a criminal justice system analysis

As with most national criminal justice data, which tends to be outdated, incomplete, and inconsistent,10 data on jail admissions is extremely limited. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) publishes basic descriptive statistics about the 740,000 individuals in jail on a given day in its annual Jail Inmates reports, and it published a more in-depth Profile of Jail Inmates in 2004, based on a 2002 survey. Yet even basic descriptions of the millions of other individuals who are arrested and jailed over the course of the year are conspicuously absent from the data. Until now, there has not even been an answer to the basic question: how many individuals are arrested and booked into jails in a given year? This lack of data restricts policymakers’ ability to understand and address the high number of yearly arrests and jail admissions.

In order to answer this question, we had to turn to public health data: the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). But because it was not intended to be used to assess justice-involved populations specifically, its sample excludes two groups that are likely to be arrested but are difficult targets for a survey: incarcerated people (in jails and prisons) and unsheltered homeless people.11 The exclusion of people who were incarcerated or unsheltered homeless when they otherwise would have been surveyed creates a limitation to our analysis, since many were likely arrested and jailed during 2017.

Because of the limitations in both national criminal justice and homelessness data, there is no obvious way to supplement the NSDUH to estimate the number of people who were arrested and booked in 2017 but excluded from the survey. Neither the BJS nor FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program program keeps track of the number of unique individuals arrested or jailed over the course of a year. Nevertheless, given the high rate of weekly jail turnover (54%) and the fact that the average length of stay in jails in 2017 was just 26 days, we concluded that most of the people who made up the 10.6 million total jail admissions in 2017 were likely still included in NSDUH.

Despite the limitations of the NSDUH sample, the survey offers the most comprehensive nationally representative data available to describe people who are arrested and jailed, whether once or many times in a year. Our analysis shows there are important differences between those jailed just once and those jailed multiple times — differences that have clear policy implications — but the full scope of these differences will remain unknown until we improve arrest and jail data collection efforts.

Data Analysis

For our analysis, we used the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) public online data analysis system (PDAS) to run cross tabulations on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2017. Our analysis included the variables NOBOOKY2 for the number of times arrested and booked, EDUHIGHCAT for education, NEWRACE2 for race, IRPINC3 for income, HIVAIDSEV for HIV status, BKSRVIOL for whether someone had committed a violent offense, UDPYILAL for substance use disorder, SMMIYR_U for serious or moderate mental illness, SPDYR for serious psychological distress, IRWRKSTAT18 for employment, CIRROSEVR for cirrhosis, HRTCONDEV for heart condition, and HEPBCEVER. In order to look at what offenses people committed, we used the following variables: BKMVTHFT (theft), BKDRUNK (drunkenness), BKDRUG (drug offenses), and BKOTHOF2 (for “other offenses,” including additional drug violations, theft violations, probation and parole violations, and traffic violations).

For researchers who want to replicate our work, we found it helpful to take the steps discussed below. When possible, we used variables that were recoded and imputed by SAMHSA so that “Bad data” “blank” “refused” or “don’t know” responses were already accounted for and excluded in our analysis and weighting. For variables where SAMHSA did not provide a recoded version, we recoded all missing data, such as “Bad data,” “Refused,” “Blank,” and “Don’t Know,” into “NA.”

We took additional steps for some of the of the variables:

- For arrests, we recoded “Legitimate Skip” and “No” responses into “No.” (“Legitimate Skip” indicates that the respondent was not asked how many times they were arrested and booked in the past 12 months, because they had previously responded that they had never been arrested).

- We excluded individuals between 12 and 17 years old from our analyses of the relationships between arrest and education, employment, and income, since youths are typically still in school at those ages rather than the labor force.

Footnotes

This number represents a minimum because the survey excludes people who were in jail or prison during data collection. See the methodology and the sidebar about the survey for details. ↩

Our analysis finds that 27% of survey respondents who were arrested and booked into jail in the past 12 months reported being arrested and booked more than once in the same year. This percentage, however, very likely underestimates the frequency with which individuals return to jail within a year. As the methodology and sidebar detail, our analysis is based on data from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a public health survey that excludes an unknown number of people who were in jail at the time they were eligible to participate in the survey. We know of no other published national one year re-arrest rate after release from jail, although a 2006 presentation by a Bureau of Justice Statistics expert mentions that 71.1% are incarcerated twice in 12 months; unfortunately the underlying data appears to be unpublished.

In lieu of a national rate, we looked at reports from counties around the country, which have reported a range of one year re-arrest rates for people released from jails. Most of these rates are higher than our conservative estimate of 27%. For example, Philadelphia reported in 2015 that 36.9% of individuals released from county jails to the city of Philadelphia were re-arrested within one year. Dallas County, Texas, reported one year re-arrest rates ranging from 11% to 50% for people booked into the jail from 2011-2014, which varied by risk level and prior contact with the county’s behavioral health system. And of those sentenced to probation in New York City in 2016, 18% were re-arrested for felony charges alone within one year. ↩

NSDUH asks how many times someone has been arrested and booked in the past year, which we use as a proxy for arrested and jailed. Data from the Vera Institute of Justice shows that almost all arrests lead to at least some time in jail. ↩

Also excluded, but less relevant for calculating arrest history are “active duty military,” people living in “long-term hospitals,” nursing homes, and “juveniles younger than 12 years old.” ↩

By comparison, 40% of the U.S. adult population has no more than a high school education. Source: U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey, 2017 Annual Social and Economic Supplement, Table 1 showing that 39.9% of the civilian noninstitutionalized population in the United States (aged 18 and over) had a high school education or less in 2017. ↩

NSDUH defines serious violent offense as aggravated assault, forcible rape, and murder, homicide, or nonnegligent manslaughter. The most frequent reasons for arrest were typically lower level offenses, including: drug charges (23%); driving under the influence (19%); “other assault” (which includes simple assault and battery and is not considered a serious violent offense) (17%); theft (13%); drunkenness (7%); violation of a court order, probation, or parole, and perjury (7%); and traffic violations (5%). ↩

This report uses the term “substance use disorder” to describe the survey’s data about dependence or abuse of illicit drugs or alcohol during the past 12 months. ↩

When local governments fail to provide services to help people meet their court dates, they set up their constituents to fail by converting arrests avoided into arrests delayed. ↩

Despite the fact that they are cheaper and more effective than incarceration, some states and counties do not fully fund diversion programs and instead require participants to pay. This creates to a two-tiered justice system in which diversion programs are inaccessible to the poor, a group disproportionately impacted by incarceration. ↩

For example, the most recent Profile of Jail Inmates report was released fifteen years ago in 2004, based on 2002 data. The FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program relies on local agency-reported arrest data, but many police departments report incomplete data, or do not submit any data at all, and the FBI relies on an algorithm to fill in these gaps. Because of incomplete data and varying levels of participation, the FBI cautions against making any direct comparison between data across years. ↩

As noted in footnote 4, “active duty military,” people living in “long-term hospitals,” nursing homes, and “juveniles younger than 12 years old” are also excluded, but less relevant for arrest history. ↩

Appendix

To benefit other researchers who wish to build upon our analysis or need the precise data behind our graphs, this appendix shares our complete data. The first appendix corresponds with the first part of the report focusing on those with multiple arrests (that is, two or more arrests within 12 months). The second table corresponds with the frequent utilizer section, focusing on the subset of people with multiple arrests that are arrested three or more times within a year.

Note that, due to rounding, percentages may not total 100%.

| Everyone surveyed | No arrests in the past year | 1 arrest in the past year | Multiple arrests in the past year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed full time | 45.26% | 45.44% | 44.28% | 32.74% |

| Employed part time | 11.78% | 11.81% | 10.58% | 9.43% |

| Unemployed | 3.94% | 3.72% | 12.39% | 15.07% |

| Other | 29.85% | 29.86% | 25.74% | 33.53% |

| 12-17 Year olds | 9.17% | 9.16% | 7.01% | 9.23% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 62.76% | 63.15% | 53.49% | 45.79% |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American | 12.08% | 11.80% | 20.70% | 28.08% |

| Non-Hispanic Native American or Alaskan Native | 0.54% | 0.51% | 2.66% | 2.46% |

| Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.39% | 0.38% | 1.02% | 1.20% |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 5.62% | 5.72% | 1.64% | 1.29% |

| Non-Hispanic more than one race | 1.80% | 1.78% | 2.93% | 3.23% |

| Hispanic | 16.80% | 16.67% | 17.56% | 17.96% |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48.51% | 47.98% | 66.88% | 77.71% |

| Female | 51.49% | 52.02% | 33.12% | 22.29% |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 11.13% | 10.72% | 20.21% | 35.91% |

| High school graduate | 22.15% | 21.93% | 30.62% | 29.61% |

| Some college or associates degree | 28.23% | 28.30% | 32.19% | 21.29% |

| College graduate | 29.32% | 29.88% | 9.97% | 3.96% |

| 12-17 Year olds | 9.17% | 9.16% | 7.01% | 9.23% |

| Income | ||||

| Less than $10,000 | 21.63% | 21.18% | 35.85% | 48.60% |

| $10,000 — $19,999 | 17.89% | 17.66% | 27.10% | 29.35% |

| $20,000 — $29,999 | 13.11% | 13.07% | 14.57% | 12.86% |

| $30,000 — $39,999 | 10.88% | 11.01% | 6.76% | 4.18% |

| $40,000 — $49,999 | 8.65% | 8.76% | 4.82% | 1.24% |

| $50,000 — $74,999 | 12.62% | 12.77% | 8.09% | 3.02% |

| $75,000 or more | 15.22% | 15.55% | 2.81% | 0.76% |

| Covered by any health insurance | ||||

| Yes | 90.58% | 90.99% | 75.69% | 71.84% |

| No | 8.87% | 8.49% | 23.35% | 27.17% |

| N/A | 0.56% | 0.52% | 0.96% | 0.99% |

| Past year serious or moderate mental illness | ||||

| Yes | 9.50% | 9.23% | 22.45% | 24.78% |

| No | 90.50% | 90.77% | 77.55% | 75.22% |

| Past year psychological distress | ||||

| Yes | 11.22% | 10.88% | 26.72% | 30.15% |

| No | 88.78% | 89.12% | 73.28% | 69.85% |

| Past year illicit drug or alcohol dependence or abuse | ||||

| Yes | 7.27% | 6.63% | 36.27% | 51.54% |

| No | 92.73% | 93.37% | 63.73% | 48.46% |

| HIV | ||||

| Yes | 0.16% | 0.15% | 0.35% | 1.68% |

| No | 98.80% | 98.95% | 98.72% | 96.31% |

| N/A | 1.04% | 0.90% | 0.93% | 3.01% |

| Everyone surveyed | No arrests in the past year | 1 arrest in the past year | 2 arrests in the past year | 3 or more arrests in the past year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed full time | 45.26% | 45.44% | 44.28% | 34.18% | 29.62% |

| Employed part time | 11.78% | 11.81% | 10.58% | 10.78% | 6.48% |

| Unemployed | 3.94% | 3.72% | 12.39% | 14.24% | 16.88% |

| Other | 29.85% | 29.86% | 25.74% | 33.76% | 33.03% |

| 12-17 Year olds | 9.17% | 9.16% | 7.01% | 7.03% | 13.99% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 62.76% | 63.15% | 53.49% | 47.32% | 42.46% |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American | 12.08% | 11.80% | 20.70% | 21.63% | 42.08% |

| Non-Hispanic Native American or Alaskan Native | 0.54% | 0.51% | 2.66% | 2.05% | 3.36% |

| Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.39% | 0.38% | 1.02% | 1.63% | 0.27% |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 5.62% | 5.72% | 1.64% | 1.71% | 0.38% |

| Non-Hispanic more than one race | 1.80% | 1.78% | 2.93% | 3.81% | 1.96% |

| Hispanic | 16.80% | 16.67% | 17.56% | 21.86% | 9.50% |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 48.51% | 47.98% | 66.88% | 77.00% | 79.25% |

| Female | 51.49% | 52.02% | 33.12% | 23.00% | 20.75% |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 11.13% | 10.72% | 20.21% | 34.76% | 38.42% |

| High school graduate | 22.15% | 21.93% | 30.62% | 26.92% | 35.43% |

| Some college or associates degree | 28.23% | 28.30% | 32.19% | 26.26% | 10.51% |

| College graduate | 29.32% | 29.88% | 9.97% | 5.03% | 1.64% |

| 12-17 Year olds | 9.17% | 9.16% | 7.01% | 7.03% | 13.99% |

| Income | |||||

| Less than $10,000 | 21.63% | 21.18% | 35.85% | 48.02% | 49.96% |

| $10,000 – $19,999 | 17.89% | 17.66% | 27.10% | 26.68% | 35.60% |

| $20,000 – $29,999 | 13.11% | 13.07% | 14.57% | 15.12% | 7.56% |

| $30,000 – $39,999 | 10.88% | 11.01% | 6.76% | 4.73% | 2.89% |

| $40,000 – $49,999 | 8.65% | 8.76% | 4.82% | 0.94% | 1.95% |

| $50,000 – $74,999 | 12.62% | 12.77% | 8.09% | 3.72% | 1.36% |

| $75,000 or more | 15.22% | 15.55% | 2.81% | 0.78% | 0.69% |

| Covered by any health insurance | |||||

| Yes | 90.58% | 90.99% | 75.69% | 72.13% | 71.19% |

| No | 8.87% | 8.49% | 23.35% | 27.38% | 26.72% |

| N/A | 0.56% | 0.52% | 0.96% | 0.48% | 2.09% |

| Past year serious or moderate mental illness | |||||

| Yes | 9.50% | 9.23% | 22.45% | 23.91% | 26.82% |

| No | 90.50% | 90.77% | 77.55% | 76.09% | 73.18% |

| Past year psychological distress | |||||

| Yes | 11.22% | 10.88% | 26.72% | 27.25% | 36.94% |

| No | 88.78% | 89.12% | 73.28% | 72.75% | 63.06% |

| Past year illicit drug or alcohol dependence or abuse | |||||

| Yes | 7.27% | 6.63% | 36.27% | 47.33% | 60.66% |

| No | 92.73% | 93.37% | 63.73% | 52.67% | 39.34% |

| HIV | |||||

| Yes | 0.16% | 0.15% | 0.35% | 0.56% | 4.12% |

| No | 98.80% | 98.95% | 98.72% | 96.13% | 93.52% |

| N/A | 1.04% | 0.90% | 0.93% | 3.31% | 2.37% |

| Hepatitis B or C | |||||

| Yes | 1.09% | 1.04% | 2.50% | 9.47% | 2.43% |

| No | 97.87% | 98.06% | 96.57% | 87.22% | 95.21% |

| N/A | 1.04% | 0.90% | 0.93% | 3.31% | 2.37% |

| Cirrhosis | |||||

| Yes | 0.22% | 0.21% | 0.86% | 0.55% | 3.47% |

| No | 98.74% | 98.89% | 98.21% | 96.14% | 94.16% |

| N/A | 1.04% | 0.90% | 0.93% | 3.31% | 2.37% |

| Heart Condition | |||||

| Yes | 9.66% | 9.73% | 5.36% | 6.21% | 14.56% |

| No | 89.31% | 89.37% | 93.71% | 90.48% | 83.07% |

| N/A | 1.04% | 0.90% | 0.93% | 3.31% | 2.37% |

| Number of emergency room visits in the past year | |||||

| None | 72.33% | 72.93% | 51.55% | 53.48% | 42.66% |

| One | 14.18% | 14.05% | 22.49% | 21.04% | 18.26% |

| Two | 7.08% | 6.94% | 12.32% | 16.30% | 23.52% |

| Three plus | 4.31% | 4.16% | 9.82% | 9.13% | 12.33% |

| N/A | 2.11% | 1.92% | 3.81% | 0.05% | 3.23% |

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. Through accessible, big-picture reports, the organization helps the public engage more fully in criminal justice reform. Its previous reports Era of Mass Expansion and Detaining the Poor helped put the need for jail and bail reform into the national conversation. More recently, it published, by the same author, Does our county really need a bigger jail? A guide for avoiding unnecessary jail expansion. The Prison Policy Initiative also leads the nation’s fight against prison-based gerrymandering and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone and video calling industries.

About the authors

Alexi Jones is a Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. Since joining the Prison Policy Initiative, Lexi has authored Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and supervision by state, which shows that prison is just one piece of the much larger picture of correctional control, discusses the harms of probation in particular, and provides breakdowns of the criminal justice system in each state. Most recently, she authored Does our county really need a bigger jail? A guide for avoiding unnecessary jail expansion and co-authored State of Phone Justice: Local jails, state prisons, and phone providers with Peter Wagner.

Wendy Sawyer is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. She is the co-author, with Peter Wagner, of Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie (2018 and 2019) and States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2018. She is also the author of Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie and The Gender Divide: Tracking women’s state prison growth, as well as the 2016 report Punishing Poverty: The high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible thanks to the generous support of the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, and the contributions of individuals across the country who support justice reform. Wanda Bertram and Peter Wagner provided invaluable feedback and editorial guidance. Lucius Couloute, Mack Finkel, and Dan Kopf helped answer critical data questions, and Roxanne Daniel provided research assistance.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.