Protecting Written Family Communication in Jails: A 50-State Survey

by Corey Frost

May 19, 2016

Executive Summary

As documented in our 2013 report, Return to Sender: Postcard-only Mail Policies in Jails, some jails are experimenting with a very harmful policy: banning letters from home. This policy undermines the ability of incarcerated people to maintain the family and community ties that are essential to post-release success.

Return to Sender found that the jails experimenting with such shortsighted policies were concentrated in just 13 states. We later discovered that forwarding-thinking regulations issued by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards were responsible for the fact that no jails in Texas ban letters from home.

To determine whether other states have similar rules that would prohibit or discourage jails from banning letters from home, this report reviews which agencies in each state provide rules, guidelines, or best practices to local jails and uncovers what, if anything, these entities say about mail that people in jail may send or receive. As expected, we find a strong correlation between the states that have strong language protecting letter writing and the states in which no jails are experimenting with banning letters.

We conclude by recommending that the entities that oversee jails adopt guidelines that emphasize the importance of written communication and forbid the use of letter bans.

Introduction

A number of sheriffs across the country are banning letters and restricting the written correspondence of those in jail to postcards. The difference in postage is slight: postcards can be mailed for $0.35 and a first-class letter stamp is $0.49. However, while a postcard includes only a few paragraphs, a letter enclosed in an envelope can contain up to eight double-sided pages of written text.1 What started as a bad practice in a few places spread to jails in at least 13 states. Since at least 2009, a small number of publishers and incarcerated people have challenged the constitutionality of postcard-only policies. Although these challenges have had mixed success,2 the trend of sheriffs adopting postcard-only policies appears to have slowed in the last 2 years, perhaps to avoid litigation on the issue.

Such bans violate correctional best practices by jeopardizing family ties and inhibiting incarcerated people’s ability to maintain their personal and professional affairs, which have been proven to facilitate reentry and reduce recidivism.3 Although people in jails with letter bans may still communicate with friends and loved ones through postcards, this alternative is not an adequate substitute for communicating through letters. Not only is there no privacy when communicating via postcard, but banning letters also places a higher economic burden on those in jail. Each word written on a postcard is 34 times as expensive as words written in letters.4 Given the exorbitant cost of making phone calls from jail and the limited times during which people may visit those in jail, written communication is vital. But its existence is being threatened.

Because jails operate in 3,300 local government systems and are sometimes led by elected officials with minimal criminal justice expertise, we saw an urgent need to identify which entities, if any, in each state define and enforce best practices, particularly as it relates to mail policies, in jails.

Notably, when the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) updated its National Detention Standards in 2011, it included a new stipulation that “[f]acilities shall not limit detainees to postcards and shall allow envelope mailings.”5 Despite the commitment of agencies like ICE to promote written correspondence, a number of jails are experimenting with these bans.

This report was prompted by two discoveries shortly after the 2013 publication of our report about jail letter bans. First, we found that Texas has a statewide policy that prohibits the use of letter bans in local jails,6 and second, we observed that no local jails in Texas have such a letter ban. The mail protection policy was enacted by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, an agency established by the state legislature to set minimum standards that all jails in the state must meet. We wondered whether other states have similar policies which prohibit the use of letter bans in local jails.

For this briefing, we set out to conduct a state-by-state survey to answer the following three questions:

- In each state, what entity oversees/regulates jails?

- What, if anything, does that entity say about banning personal letters to and from people incarcerated in jails? Or, in states where the relevant entity could not be determined, or where guidelines for jails could not be found, what guidelines or best practices govern mail in the state prison system?

- Under what circumstances may jail administrators restrict mail?

Findings & Patterns

In each state, what entity oversees/regulates jails?

In all 50 states, specific entities have the authority to monitor and inspect local jails. These entities include state government regulatory bodies, non-profit advocacy groups with formal rights of access, and Ombudsman or Inspector General offices that respond to complaints.7 Other entities that hold discretionary monitoring authority narrowly serve subpopulations within local jails, such as persons with disabilities, the elderly, and juveniles. Using a previous study conducted by Michele Deitch, Senior Lecturer at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs and School of Law at the University of Texas, and our own research, we identified the relevant regulatory entities in all 50 states. The entities were divided into three categories: those with binding authority over jails, those with advisory authority over jails, and those whose authority status could not be determined. A list of each state’s relevant entities and their authoritative status can be found in Appendix A.

What, if anything, does that entity say about banning personal letters to and from incarcerated people?

In states where the relevant entity could not be determined, or where guidelines for jails could not be found, what guidelines or best practices govern mail in the state prison system?

Through internet searches, we found mail guidelines established by entities overseeing jails or state prisons in most states. In states where jail guidelines could not be identified, we analyzed state prison policies. Although these state prison policies are not directly binding on jails, they do provide evidence for what corrections officials in the same state consider appropriate.

All of the identified guidelines specify limitations on the extent to which incarcerated people’s mail may be restricted. Although only the ICE guidelines and those enacted by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards specifically address restrictions limiting written correspondence to the use of postcards, most guidelines say there shall be no limits on the volume or length of letters that incarcerated individuals may send. Hence, restricting the written communication of incarcerated people to postcards contradicts the spirit, if not the letter, of the guidelines.

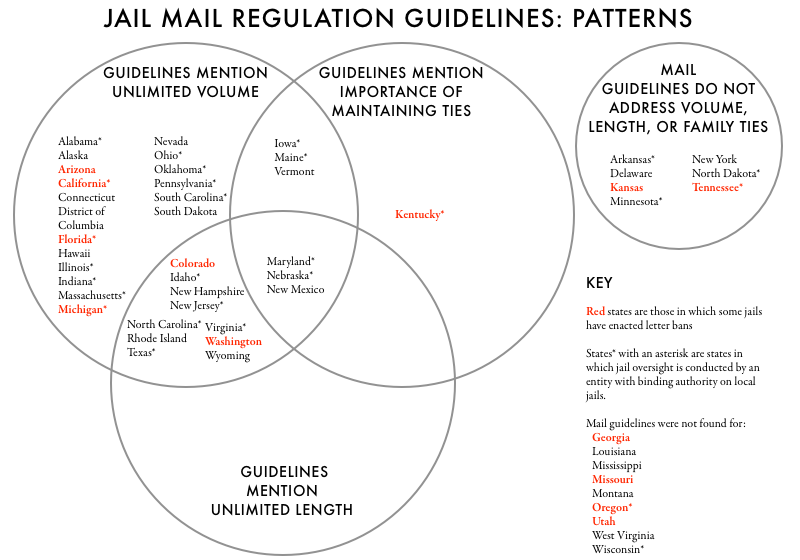

We organized these policies into three groups based on their patterns:

- Guidelines that prohibit restrictions on “length” of mail

Example:- “There shall be no restrictions on the number of letters, length, language, content or source of mail or publications, except when there is a reasonable belief that the limitation is necessary to protect public safety or institutional order and security.” [Nebraska Department of Corrections]

- Guidelines that prohibit restrictions on “volume” or “amount” of letters

Examples:- “When the inmate bears the mailing cost, there is no limit on the volume of letters the offender can send or receive…” [Rhode Island Department of Corrections]

- “There is no limitation put on the amount of mail an inmate may receive regardless of custody or detention status.” [Arizona Department of Corrections]

- Guidelines that mention the importance of communication to maintaining ties with family and community

Examples:- “It is important that there be constructive correspondence between prisoners and their families and others as a means to maintain ties with the community. Each facility shall provide inmates with the means to engage in such correspondence.” [Maine Department of Corrections]

- “[The regulatory entity] encourages correspondence on a wholesome and constructive level between inmates and members of their families, as well as friends or associates…” [New Mexico Department of Corrections]

As illustrated in Figure 1, most states draw their policies from a combination of these principles:

Figure 1. This Venn diagram shows the relevant state guidelines for mail policies in each state, along with whether those guidelines are binding on jails and whether jails have been experimenting with letter bans in that state. For the specific policies associated with each state, see Appendix A.

Figure 1. This Venn diagram shows the relevant state guidelines for mail policies in each state, along with whether those guidelines are binding on jails and whether jails have been experimenting with letter bans in that state. For the specific policies associated with each state, see Appendix A.

We found that most guidelines include language that protects the rights of incarcerated people to send an unlimited “volume” or “amount” of letters. However, “volume” and “amount” are not defined in any of the guidelines, nor do any of guidelines specify what counts as a “letter.” Nonetheless, these guidelines are clearly intended to protect correspondence between people in jail and their loved ones. Hence, letter bans violate the spirit of guidelines that allow an unlimited “volume” or “amount” of letters.

A subset of these guidelines is more specific by also stipulating that jails may not restrict the “length” of the pieces of mail that incarcerated people send or receive. We consider this language more helpful than only discussing “volume” or “amount” because postcards are inherently shorter than letters. Hence, we expect it to be harder for sheriffs to justify letter bans under guidelines that prohibit restrictions on the length of mail.

We found a distinct correlation between the states that have stronger language to protect letter writing in jails and the states in which sheriffs have not enacted letter bans. In particular, states whose jail oversight entity guidelines mention the importance of maintaining ties do not tend to be among the states where sheriffs enact letter bans. For example, the director of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards told us in an interview that the organization’s standards ensuring that incarcerated people in local jails be permitted to send an unlimited number of letters set clear expectations for all county and municipal jail administrators throughout the state. Conversely, sheriffs were most likely to enact letter bans in states with no guidelines governing mail to and from incarcerated people, or states in which guidelines did not specifically address how such mail may be restricted.

Under what circumstances may jail administrators restrict mail?

The policies of several state entities outline the circumstances under which sheriffs or jail administrators may restrict mail. Almost all of these states allow for restrictions when such limitations are deemed necessary to protect “public safety or institutional order and security.”

Sheriffs in a small number of states prohibit mail restrictions except when they are used for disciplinary reasons:

- “There shall be no limit placed on the number of letters an inmate may write or receive at personal expense, except as a disciplinary penalty.” [Connecticut Department of Corrections]

- “No restrictions will be placed on an inmate’s mail for disciplinary reasons unless the inmate specifically abuses the use of mail, in which case restrictions are imposed through due process.” [Vermont Department of Corrections]

Most state policies only require that sheriffs or jail administrators who enact restrictions have “reasonable belief” that such restrictions are necessary to protect safety and security. A small number of states, however, require a showing of “clear and convincing evidence” to justify restrictions on mail:

- “Written policy, procedure, and practice shall ensure that there is no limit on the volume of mail an inmate may send or receive, or on the length, language, content or source of such mail, except where there is clear or convincing evidence to justify such limitations.” (emphasis added) [Virginia Department of Corrections]

In sum, our findings demonstrate that regulations on mail in local jails vary from state to state. Though some states restrict mail for security purposes, no set of guidelines specifically limits written correspondence to the use of postcards. The language used in mail guidelines differs in strength, but most states protect the volume, length, or amount of letters that jail inmates may send or receive. States that explicitly recognize the importance of using written correspondence in maintaining relational ties are the least likely to ban letters in favor of postcards. States that lack such guidelines are the most likely to implement letter bans.

Policy Recommendations

- Sheriffs and jail administrators should allow incarcerated people to send and receive letters and should not place limitations on the length of the letters or on the amount of letters an incarcerated person may send or receive. Sheriffs and jail administrators should never consider postcards to be an adequate substitute for letters.

- Entities responsible for developing guidelines or best practices for local jails should adopt guidelines that forbid letter bans and ensure that incarcerated people are permitted to send and receive letters of unlimited length.

- Ideal guidelines would accomplish the following:

- Include a general statement about the importance of written communication for maintaining critical family and community ties;

- Place no limits on either the sending or receiving letters, or on either the volume or length of letters that an incarcerated person may send or receive;8 and

- Specify that restrictions on mail to and/or from incarcerated people will only be permitted if there is clear and convincing evidence that such restrictions are necessary to promote safety.

Methods

In a 2010 Pace Law Review article, Michele Deitch identified state-level entities that oversee local jails in all 50 states.9 These entities can be divided into three categories: regulatory bodies that are part of state governments (e.g., California’s Corrections Standards Authority), non-profit advocacy groups with formal rights of access (e.g., John Howard Association of Illinois), and Ombudsman or Inspector General offices that respond to complaints (e.g., Hawaii’s Office of the Ombudsman). Deitch also classified entities with discretionary monitoring authority that serve specific subpopulations within local jails (e.g., Disability Rights Wisconsin, Colorado’s Legal Center for People with Disabilities and Older People). For the purposes of this briefing, however, we did not include entities that represent subpopulations within local jails, but instead focused only on those entities that set standards that affect the entire jail population. In addition, we identified a small number of advisory entities not included in Deitch’s work.

In order to determine what policies or best practices regulatory entities provide to local jails, we began by searching the websites of the entities identified by Deitch’s 50-state survey. Most websites included a set of guidelines or a link to the state administrative code governing correctional facilities.

In cases where we could not identify the entity that provides oversight of local jails in a given state, where the guidelines could not be located, or where the guidelines did not address mail specifically, we looked to that state’s department of corrections for guidelines on mail. See Appendix A for the list of entities that we used in this report.

| State | Agency(ies) Setting Standards for Jails | Binding Authority? |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Alabama Board of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Alaska | Alaska Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Arizona | Arizona Department of Corrections Arizona Sheriffs’ Association | Advisory Advisory |

| Arkansas | The Criminal Detention Facilities Review Committees (within the Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration) | Binding |

| California | Board of State and Community Corrections (formerly the California Corrections Standards Authority) | Binding |

| Colorado | Colorado Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Connecticut | Connecticut Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Delaware | Delaware Department of Corrections Delaware Council on Correction | Undetermined Undetermined |

| District of Columbia | District of Columbia Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Florida | Florida Model Jail Standards Committee Florida Corrections Accreditation Commission (FCAC) | Binding Advisory |

| Georgia | Georgia Board of Corrections Georgia Jail Association | Undetermined Advisory |

| Hawaii | Hawaii Department of Public Safety, Division of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Idaho | Idaho Sheriffs’ Association | Binding |

| Illinois | Illinois Department of Corrections Jail and Detention Standards Unit John Howard Association | Advisory Binding |

| Indiana | Indiana Department of Corrections | Binding |

| Iowa | Iowa Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Kansas | Kansas Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Kentucky | Kentucky Department of Corrections, Division of Local Facilities Jail Services Branch | Undetermined |

| Louisiana | Louisiana Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Criminal Justice | Undetermined |

| Maine | Maine Department of Corrections | Binding |

| Maryland | Department of Public Safety & Correctional Services Commission on Correctional Standards | Advisory |

| Massachusetts | Massachusetts Department of Corrections, Policy Development and Compliance Unit | Undetermined |

| Michigan | Michigan Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Minnesota | Minnesota Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Mississippi | Mississippi Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Missouri | Missouri Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Montana | Montana Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Nebraska | Department of Correctional Services Nebraska Jail Standards Board (within the Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice) | Binding Advisory |

| Nevada | Nevada Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| New Hampshire | New Hampshire Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| New Jersey | New Jersey Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| New Mexico | New Mexico Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| New York | New York Commission on Corrections Correctional Association of New York | Binding Advisory |

| North Carolina | North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Health Service Regulation, Jail and Detention Section (for Jails) North Carolina Department of Public Safety (for state prisons) | Binding (jails) Binding (prisons) |

| North Dakota | North Dakota Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Training and County Facilities | Undetermined |

| Ohio | Ohio Correctional Institution Inspection Committee Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction | Binding (jails) Binding (prisons) |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma Department of Health, Jail Inspection Division | Binding |

| Oregon | Oregon Department of Corrections - Community Corrections | Binding |

| Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, Office of County Inspections and Services (OCIS) | Advisory |

| Rhode Island | Rhode Island Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| South Carolina | Department of Corrections, Division of Inspections and Operational Review South Carolina Association of Counties | Undetermined Advisory (jails) |

| South Dakota | South Dakota Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Tennessee | Tennessee Corrections Institute | Binding |

| Texas | Texas Commission on Jail Standards | Binding |

| Utah | Utah Sheriffs’ Association | Advisory |

| Vermont | Vermont Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| Virginia | Virginia Department of Corrections, Compliance and Accreditation Unit | Undetermined |

| Washington | Washington Department of Corrections | Undetermined |

| West Virginia | West Virginia Regional Jail and Correctional Facility Authority | Undetermined |

| Wisconsin | Wisconsin Department of Corrections, Office of Detention Facilities | Binding |

| Wyoming | Wyoming Department of Corrections | Advisory |

Appendix B: Jail mail policies in depth

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Michele Deitch for sharing her research on this topic. I would also like to thank Peter Wagner and the staff at Prison Policy Initiative for their guidance and support.

About the author

Corey Frost is a third year student at the University of North Carolina School of Law. The original research for this briefing was conducted in his first year of law school through UNC’s Pro Bono Program, and the first draft was prepared as part of Corey’s participation in Prison Policy Initiative’s Alternative Spring Break project. He was the recipient of the UNC Law Pro Bono Publico Award for 1L Student of the Year. He will join Legal Aid of North Carolina as an Everett Fellow in Fall 2016.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to challenge over-criminalization and mass incarceration through research, advocacy, and organizing. The Easthampton, Massachusetts-based organization shows how the United States’ excessive and unequal use of punishment and institutional control harms individuals and undermines our communities' and national well-being through filling data gaps in the national movement for criminal justice reform and sparking targeted campaigns.

Prison Policy Initiative is most famous for its work documenting how mass incarceration skews our democracy and how the prison and jail telephone and video visitation industries punish the families of incarcerated people. Protecting Written Family Communication in Jails: A 50-State Survey follows up Prison Policy Initiative’s 2013 report on jail mail restrictions, Return to Sender: Postcard-only Mail Policies in Jails.

Footnotes

Leah Sakala, Return to Sender: Postcard-Only Mail Policies in Jail (Prison Policy Initiative, Feb. 7, 2013). ↩

See e.g., Prison Legal News v. Columbia County, 942 F.Supp.2d 1068 (D. Ore. April 24, 2013) (finding postcard-only policy a violation of the First Amendment); Covell v. Arpaio, 662 F.Supp2d 1146 (D.Ariz. Sept. 24, 2009) (finding postcard-only policy reasonably related to the legitimate penological interest in reducing contraband); Cox v. Denning, Civil No. 12-2571, 2014 WL 4843951, *14-23 (D. Kansas Sept. 29, 2014) (finding postcard-only policy not rationally related to legitimate penological interests); Prison Legal News v. County of Ventura, Civil No. 14-0773, 2014 WL 2736103, *3-8 (C.D. Cal. June 16, 2014) appeal dismissed (Sept. 2, 2014) (ordering the suspension of enforcement of the postcard-only policy because constitutional challenge to the policy found likely to succeed on the merits); Prison Legal News v. Chapman, Civil No. 3:12-cv-00125, 2014 WL 4247772, *4-5 (M.D.Ga. Aug. 26, 2014) (finding postcard-only policy constitutional after weighing Turner factors); Prison Legal News v. Bezotte, Civil No. 11-cv-13460, 2013 WL 1316714, *3-5 (E.D.Mich. March 29, 2013) (finding postcard-only policy constitutional after weighing Turner factors); Althouse v. Palm Beach County Sheriffs Office, Civil No. 12-80135, 2013 WL 536072 (S.D.Fla. Feb. 12, 2013) (finding postcard-only policy to be rationally related to legitimate penological interest of reducing contraband). ↩

Sakala (2013) ↩

Sakala (2013) ↩

Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “5.1 Correspondence and Other Mail” in 2011 Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2011), 276. ↩

Texas Commission on Jail Standards, Rule S 291.2, “Inmate Correspondence Plan.”

Deitch, Michele. “Special Populations and the Importance of Oversight.” American Journal of Criminal Law. 37 (2010): 291. ↩

For the purposes of this report, a “letter” is defined as a form of communication written on paper (as opposed to cardstock) and sealed in an envelope. “Volume” is defined as the number of separate letters an inmate may send in a given amount of time. ↩

Deitch (2010) ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.