Demonstrating that sex-offender exclusion zones undermine efforts to protect children

Most states have laws that regulate where people on the sex offender registries may live or work. The purpose of these laws is to protect children, but in some states and municipalities, these laws are drawn too broadly creating the counter-intuitive result of fewer protections and less safety.

In short, some of these laws are written in a way that unintentionally makes all or almost-all housing and employment off-limits to people on the registry. Some states compound the problem by applying harsh registry requirements on people who they concede have a very low risk of reoffending. Without housing or employment, it is harder for people on the registry to build the kind of stability that helps prevent recidivism. Many of these laws divert law enforcement resources from crime prevention to creating homelessness, which in turn makes it harder for law enforcement to monitor people on the registry.

Georgia Sheriffs were some of the biggest opponents of HB1059 because the law made enforcement so impractical that it left their communities less safe than they would have been without it.

Our mapping expertise has helped the Southern Center for Human Rights and other law firms interested in defending civil rights and improving public safety by demonstrating a basic fact of geography and geometry: If you draw large exclusion zones around a large number of places, you will make an entire community off limits. By contrast, more modest restrictions tend to be more effective.

Georgia's HB1059 (since repealed in part, with other parts still stayed by the federal courts), is the clearest example of how not to regulate the activities of people on the sex offender registry.

The Georgia law has numerous flaws, including:

- Applying to everyone on the registry, regardless of risk.

- A large exclusion zone of 1,000 feet, to be measured in the most extreme way possible, from property line to property line.

- A large number of protected places, including churches and, most critically, school bus stops. School bus stops are the most problematic, because the state's 350,000 stops are located, almost by definition, wherever there is housing.

By contrast, effective laws differ in three key ways:

- A reasonable population: limited to just people deemed to be at a high-risk of re-offending

- A reasonable distance

- A reasonable number of protected places

In the case we worked on in Georgia, two women testified that they were unable to find anywhere in five counties to live that would meet the requirements of HB1059.

As a policy and criminal justice matter, laws such as that created by HB1059 are counter-productive, but other organizations are the best experts on that. Our specialty is explaining the geographic reality of distance-based legislation.

In Georgia, we helped the Southern Center for Human Rights with their class action lawsuit, Whitaker v. Perdue, against Georgia's law. We found that because almost every tract of habitable housing in Georgia is served by one of 350,000 school bus stops, the legislature unwittingly declared all urban areas, all suburban areas and most rural areas off limits. This law was so extreme that it merited opposition from many of the state's sheriffs. We helped the Southern Center demonstrate in federal court that another flaw in the statute makes a lot of housing beyond the intended 1,000-foot protected area off limits and demonstrated the combined effect with a detailed analysis of Richmond County (Augusta, GA) and other counties.

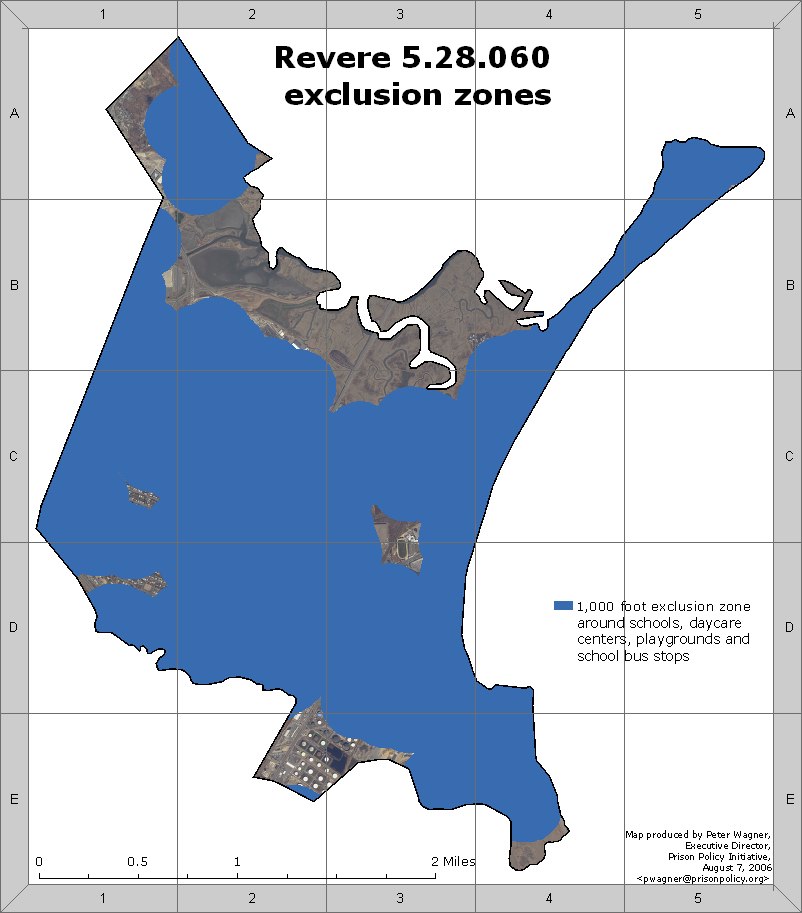

A case in the Massachusetts city of Revere serves as a clear illustration of how exclusion zones can easily blanket whole communities. We prepared an affidavit and the following map demonstrating that a city ordinance would make more than 99% of the city off-limits to people classified as level III sex offenders: