Excessive, unjust, and expensive

Fixing Connecticut's probation and parole problems

By Leah Wang and gabriel sayegh

May 2023

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Probation

- Incarceration is one mistake away

- Fees, monitoring, & other burdens

- Consequences of noncriminal violations

- Parole

- Tangled web of parole programs

- Lost gains while behind bars

- Revocation undermines success

- The promise of probation & parole reform in Connecticut

- A framework for reform

- A fairer, less costly approach

- Conclusions

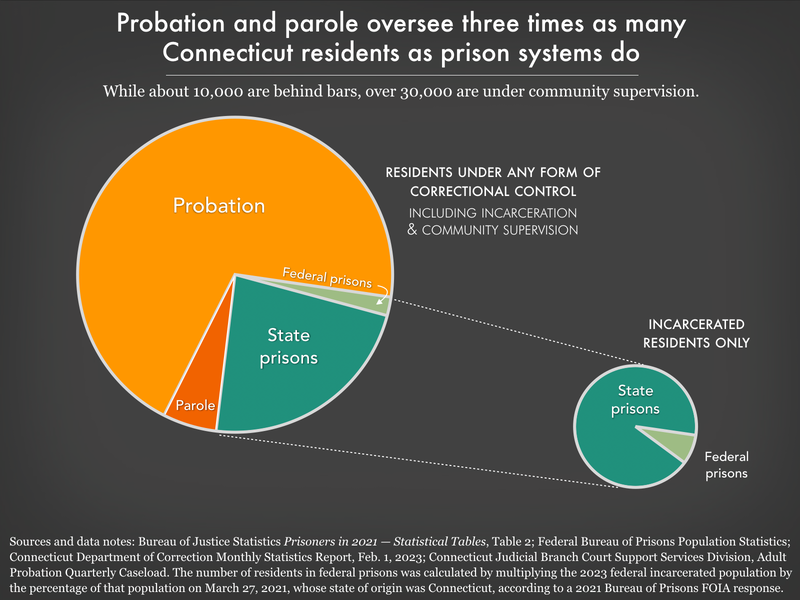

In the United States, the number of people under the surveillance of probation and parole systems is nearly twice the number of those behind bars. Community supervision, which refers mainly to probation and parole, is “too big to succeed.” (Simply defined, probation is a court-ordered “suspended” sentence served in the community, typically with a set period of supervision; parole is a conditional release after incarceration.) This is true throughout the country — and Connecticut is no exception, particularly in terms of its outsize probation system, which jeopardizes the well-being and progress of more than 30,000 people and their families.

Chronically underfunded and overly punitive, probation rarely serves as an alternative to incarceration, as it was originally intended. And people released from prison to parole supervision often struggle to rebuild their lives during the reentry process. But the sheer size of these populations is not the biggest problem: noncriminal “technical” violations of probation and parole — like missing a curfew or testing positive for alcohol or other drug use — are known drivers of mass incarceration, sending hundreds of thousands of people nationwide into jails and prisons every year. (Connecticut is one of six states that has a unified system of jails and prisons; the Department of Correction [DOC] manages both types of incarceration.)

In Connecticut, as in other states, excessive consequences for these noncriminal violations can result in incarceration. This approach disproportionately burdens communities of color and is a costly endeavor for the entire state; research and experience tell us that most community supervision does not contribute to public safety and that probation and parole populations can and must be reduced. Other states have made such changes, offering Connecticut guidance about the steps to take for reform. For instance, in 2021, New York passed the transformative Less Is More law to help break cycles of supervision and incarceration.

This report provides lawmakers and advocates fundamental information to advance essential probation and parole reforms in Connecticut, changes that will reduce unnecessary incarceration and supervision; increase fairness, justice, and public safety; and save taxpayer dollars and other resources. The report reviews the policies and data related to community supervision and technical violations in Connecticut and describes concrete ways to improve these systems. It also gives an overview of New York’s recent parole reforms, with recommendations for lawmakers and others working to shape meaningful legislation in Connecticut and beyond. Given the immediate and ongoing signs of success in New York, any state can look to the provisions of the Less Is More Act to help determine ways to reduce excessive supervision and incarcerated populations.

What follows is a deep dive into the policies and practices that entangle too many people in the web of ongoing supervision and cycles of imprisonment in Connecticut. Those who are on probation and parole live in fear of arrest and incarceration for nearly any action that could constitute a violation — a gross misuse of resources and a disservice to families in Connecticut. By allowing people to remain in their communities, the state can better provide residents the help they may need in the place where they’re most likely to succeed. Connecticut has a momentous opportunity to reshape the probation and parole systems and deliver racial, economic, and procedural justice to people under supervision.

For the 30,000 people on probation in Connecticut, incarceration is one mistake away.

As of January 1, 2023, 30,723 people — almost 1% of the population — were on probation in Connecticut.1 These 30,000 people are by far the most under any form of “correctional control” statewide: That is three times the number of people Connecticut incarcerates.2 After year upon year of declines mirroring a national trend, the probation population took an upturn in late 2021 and rose steadily in 2022.3 Every month, roughly 1,700 people in Connecticut begin probation, about 1,200 complete it, and several dozen people on probation are incarcerated for a violation.4

Although many perceive probation as a “lenient” sentence or lift it up as a model “alternative to incarceration,” it subjects tens of thousands of people in Connecticut to supervision and surveillance every day and at significant cost. What’s worse, probation’s onerous conditions act as a trip wire to incarceration. According to the Connecticut DOC’s publicly available data, supervision violations are the most common “offense” that puts people behind bars: 1 in 10 people in state prisons are listed under the offense “violation of probation or conditional discharge.” Connecticut is not unique in this manner, but reforming the system in meaningful ways would offer the state an opportunity to lead by example, reducing the unintended harms of its probation practices. State lawmakers and advocates should seize the opportunity to make the greatest impact possible by addressing the ways that probation can easily ensnare people in cycles of incarceration and surveillance.

As judges continue to order probation for people who don’t pose a risk to public safety, the state should make this system less punitive and more supportive for them. Through effective reform, Connecticut can offer commonsense incentives and fair, efficient processes to resolve compliance issues as people navigate probation requirements, treatment, work, family, and other responsibilities.

Probation supervision in Connecticut often comes with onerous fees, electronic monitoring, and other burdens that make it difficult for people to succeed.

Complying with court-ordered conditions of probation is practically a full-time job: Connecticut statute lists 17 “standard” conditions a judge can impose, including maintaining work or a course of study, undergoing treatment or counseling, meeting family obligations, and nebulous “other conditions.”5

Everyone on probation has at least one financial obligation as a condition of their probation sentence: a onetime $200 supervision fee. But Connecticut charges other fees, such as for drug testing or program participation. On a national scale, having to comply with all legal financial obligations as a standard condition of probation amounts to a mass extraction of wealth from some of the country’s poorest people and all but guarantees that many will end up behind bars. This is one reason that reforms like the ones New York recently enacted through the Less Is More Act could have an impact right away: Connecticut must prohibit incarcerating people for noncriminal violations of probation conditions (such as missed payments) that have more to do with financial insecurity than willful noncompliance.

Some people on probation in Connecticut have to wear an electronic monitoring (EM) device,6 usually called an ankle monitor or “tether.” Agencies that use EM claim it contributes to public safety, ensuring that people appear for their check-ins or court dates. But as research and countless firsthand accounts make clear, this surveillance technology is often used in ways that are discriminatory, financially exploitative, and ineffective.7 Fortunately, electronic monitoring is used infrequently among people on probation in Connecticut: As of July 2022, about 1 percent of adults on probation were required to use EM.8 In reducing the amount of time people are subject to community supervision, the state’s reforms should reduce the risk of accidentally violating one of the many absurd requirements for complying with EM, such as failing to charge the device.

Noncriminal violations of probation can land someone behind bars for weeks, even if they’ve never been sentenced to prison.

Because many people who are on probation in Connecticut were never sentenced to incarceration, being accused of a noncriminal violation could put them behind bars for the first time, an experience contributing to a litany of terrible consequences.

Someone who is accused of violating the conditions of their probation is typically arrested on a “violation of probation” warrant, as hundreds of people are in Connecticut every month.9 Alternatively, authorities can provide written notice for people to appear before a judge for an alleged violation, though no data exist regarding how often this type of notice is given. Connecticut should offer written notice as the norm, sparing many people the trauma of arrest.10

As soon as someone is taken into custody (“remanded”) or provided a notice to appear regarding a probation violation in Connecticut, a few troubling things happen:

- The probation sentence is “interrupted,” even if the court determines that there was no violation.

According to state law, time spent waiting for the revocation11 process to play out doesn’t count toward completing a probation sentence. This is grossly unfair. Connecticut can easily solve this by repealing the statute that unjustly interrupts the probation sentence “clock.” - State law allows up to four months before a revocation hearing determines the final outcome for someone on probation.

As if stopping the clock isn’t already frustrating and counterproductive, sometimes people must wait more than four months — 120 calendar days — for their hearing, such as when the courts try to resolve multiple charges at once. But as research has shown, even a few days in jail can be life-altering; 120 days can be catastrophic. - People may have an opportunity to post bail, but money bail is out of reach for many.

Although the opportunity to be released on bail may sound reasonable, money bail is too often unaffordable,12 leaving people who pose no threat to public safety locked up for weeks and months.13 The time spent behind bars awaiting a hearing comes at a steep cost to taxpayers too: At nearly $1,200 per week,14 it’s expensive to incarcerate someone in Connecticut. And that doesn’t account for lost income, lost housing and/or property, and severed connections with loved ones, which create devastating setbacks for families and entire communities. - Racial disparities in supervision keep communities of color under excessive surveillance.

No discussion of probation in Connecticut should overlook the widely documented racial disparities found at every stage and level of the state’s entire criminal justice system — in policing and arrests, in pretrial and bail practices, in jails and prisons, and in community supervision programs, including probation and parole.15 Keeping communities of color under the surveillance of the criminal legal system via probation almost guarantees that people will end up incarcerated, re-incarcerated, or perpetually struggling to make ends meet due to fees and mandatory obligations that interfere with a stable life.

The tens of thousands of people impacted by probation in Connecticut every day stand to benefit immensely from less incarceration and delay — and from more fairness and opportunity to successfully complete supervision.

Connecticut’s tangled web of parole programs

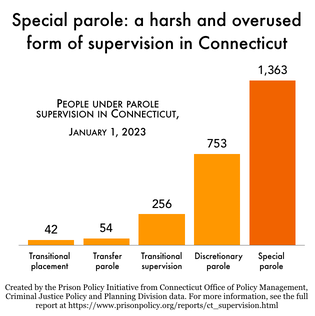

Like most states, Connecticut has discretionary parole, but “parole supervision” extends to far more people than those the parole board releases. Several types of releases from state prisons can result in parole supervision and could therefore lead to re-incarceration for violations.

The following chart describes most types of parole supervision in Connecticut as of January 1, 2023. (The rest of this report refers to these types of supervision collectively as parole unless otherwise specified.)

Types of parole supervision in Connecticut16

| Type of parole | Description | Population on January 1, 2023 17 |

|---|---|---|

| Discretionary parole | Granted to parole-eligible people by the Board of Pardons and Paroles; this typically requires a parole hearing, but legislation passed in 2015 allows the board to grant parole without a hearing for people convicted of certain crimes. | 753 |

| Special parole | Part of a sentence handed down by a sentencing judge, served after all incarceration and other supervision (including discretionary parole) is completed. Special parole, which is unique to Connecticut (though other states use the name), is like an intense form of probation. | 1,363 |

| Transfer parole | A type of parole for people granted discretionary parole but who haven’t been released from prison yet. The Board of Pardons and Paroles can decide to release people to transfer parole prior to their determined date. For some people, however, this “head start” to parole comes at a cost of “stricter supervision.” | 54 |

| Transitional placement | Specifically for people who are not eligible for discretionary parole18 but have successfully completed a term in a state-sanctioned halfway house. While remaining under supervision, people are transferred to an approved community residence or private residence. | 42 |

| Transitional supervision | For people who have sentences of two years or less, transitional supervision is available after serving 50% of their sentence. | 256 |

The disruptive role of special parole in Connecticut cannot be overstated. More people are serving this severe type of supervision sentence than are on discretionary parole — and this has been true since 2013. Fortunately, legislation that went into effect in January 2020 allows the Board of Pardons and Paroles to discharge people early from discretionary and special parole; as of August 2022, the board had granted more than 1,200 early discharges, primarily from special parole.19

Still, it should be concerning to lawmakers and advocates that so many people who have already completed a sentence of incarceration (and/or supervision) remain entangled in the state’s criminal legal system through special parole. The program is notorious; the ACLU of Connecticut has deemed it an “extreme” and “over-used” form of supervision that comes down hardest on Black and Latino residents.20

Awaiting hearings behind bars, people accused of parole violations lose the gains they’ve made.

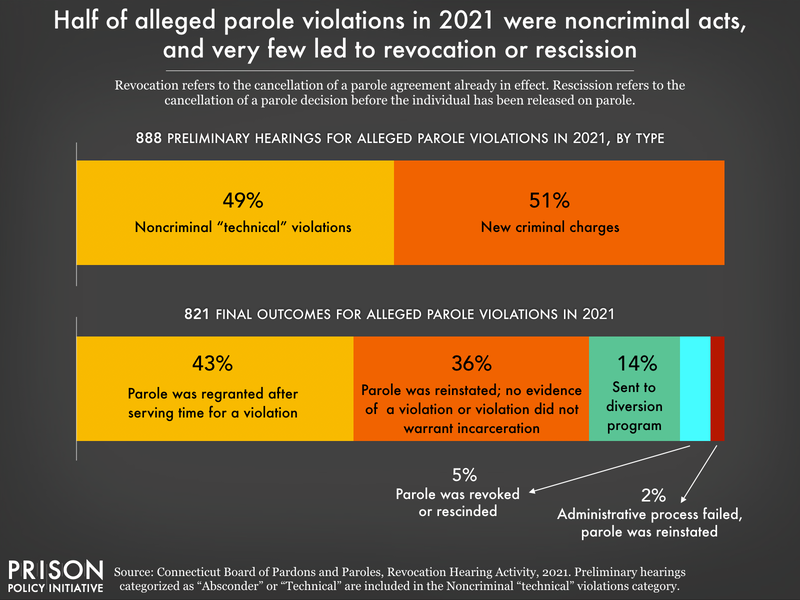

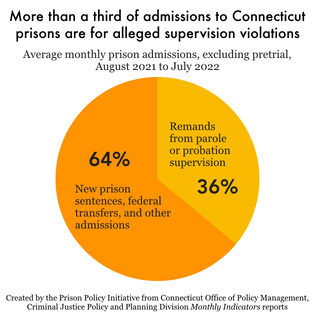

Like a probation violation, a parole violation can be “noncriminal” or “criminal” and can lead to time behind bars as the revocation hearing process plays out. Regardless of the violation type, people on parole supervision can be returned to DOC custody (“remanded”) with no right to bail, leaving them to the injustices and delays of the revocation hearing process. Every month, more than 100 people on parole supervision in Connecticut are remanded, accounting for over one-third of prison admissions (not including people who are pretrial and have not been convicted of a crime).21 And in 2021, half (49%) of all alleged parole violations were for noncriminal “technical” violations.22

The injustice of automatic re-incarceration for noncriminal violations of parole begins immediately, because state law allows a remand to take place before someone even receives official paperwork explaining their alleged violation. After being remanded, someone may be in custody for up to — and sometimes exceeding — 60 business days (12 weeks) awaiting hearings and administrative actions. (By contrast, some states, including New York under the Less Is More Act, require a notice of violation to be delivered first and instead of automatic re-incarceration.)

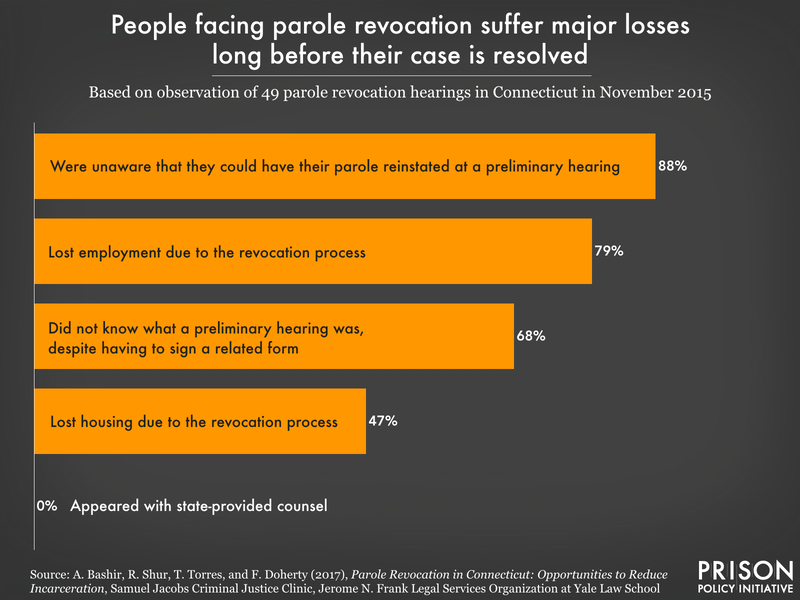

During weeks behind bars, people can lose their footing and important ties in and to their community: According to a 2017 report from Yale Law School, among people awaiting parole revocation decisions in Connecticut, a staggering 79% of those surveyed lost their jobs and almost half (47%) lost their housing.

Of 821 parole revocation processes that resolved in Connecticut in 2021, more than one-third (36%) of cases led to parole being reinstated, suggesting that at least 300 people were in prison unnecessarily, likely for multiple months. And fewer than 5% of resolved violations resulted in parole being rescinded23 or revoked.

Given how many people are eventually found not to be in violation of their parole, how many people could safely be released weeks and months earlier — or not locked up at all? The destabilizing results of sending people on parole back to prison for any slipup isn’t contributing to public safety; it’s simply a waste of time and money.

Other ways parole and revocation undermine success

- The process is expensive — for everyone.

Even though people in Connecticut aren’t charged fees for parole supervision24 or electronic monitoring,25 whenever someone is incarcerated the state eventually bills them for the cost of their incarceration, an indefensible “pay-to-stay” system driven by state statute.26

According to a class-action lawsuit filed by two Connecticut residents, the state charges people $249 a day for their incarceration, sentenced or not, under this “prison debt law.” Ending automatic re-incarceration for most noncriminal parole violations would spare many families these outrageous fees.

Meanwhile, taxpayers foot the bill of re-incarceration for noncriminal violations: Several weeks of keeping someone behind bars costs an estimated $11,500 to $14,500 in Connecticut, according to a Yale Law School report on the parole revocation process. By reducing the use of incarceration for noncriminal violations of parole, the state can reinvest the savings in reentry programming — like supportive housing — known to dramatically improve a person’s chances of successfully transitioning back into society from prison. - The concept of “good time” or “time credits” doesn’t exist in Connecticut’s parole laws — yet.

Currently, people on parole supervision don’t earn any time credits (or “good time”) — days of credit taken off their supervision term — for the days or months they’re in compliance. Earning such credits during supervision is standard practice in at least nine states, including New York now. The longer people have to be on parole, the more they need to juggle all the challenges of compliance and reentry — and the more likely they are to be brought back to prison for a minor mistake. As it stands now, people who have certain eligible types of parole can only hope that the appropriate authority will grant them an early termination. For discretionary parole, this is an onerous process with strict requirements; recent data suggest that only a handful of people are approved each month (and early termination numbers from special parole are slightly higher).27 Conversely, some states have crucial policies granting good time, building in the potential for early termination from the very beginning. For example, in New York under the Less Is More law, people earn a 30-day reduction in their parole period for every 30 days they go without receiving a technical violation. - People going through revocation hearings don’t always receive due process.

People facing parole violation allegations have the right to counsel (a lawyer) and a preliminary hearing (a court appearance in which someone can dispute a parole officer’s decision to remand them — and they may be released). But in practice, people on parole are not exercising these rights, putting themselves at greater risk of revocation and more prison time. The Yale report cited earlier found that people remanded for a violation of parole were largely unaware of their rights, even when they had been through the process before. In some cases, parole officers advised people to sign away their rights — or steered them in that direction — or didn’t provide them with opportunities to present evidence or call witnesses, two other rights afforded during revocation hearings.

In Connecticut, state statute doesn’t specify where parole revocation hearings must take place; lawmakers should require that hearings cannot be held behind the walls of a correctional facility but in a more neutral setting, as New York implemented through its Less Is More Act.

The promise of probation and parole reform in Connecticut

With nearly 35,000 people on some form of supervision in Connecticut, the state could make probation and parole fairer and more effective by drawing on the principles of New York’s Less Is More law, which is based on successful reforms from other states. Such reforms would have a wide-ranging positive impact by interrupting cycles of incarceration and excessive surveillance. But how many people will be affected?

These are the estimated gains:

- Thousands of currently active arrest warrants can be lifted and valuable resources saved by not issuing and serving hundreds of warrants for probation violations month after month.

- At least 6,000 fewer people will be arrested within two years.28

- Hundreds of people will immediately be eligible for release from Connecticut prisons, based on the noncriminal nature of their supervision violation.

- Prison populations in Connecticut could shrink by as much as 10 percent; 1 in 10 people in its state prisons are listed under “violation of probation or conditional discharge.”29

- Once the state is through calculating earned time credits, thousands of people will soon be off supervision entirely, allowing probation and parole agencies to focus on people with the greatest needs and shrinking the overall footprint of mass supervision.

- Fewer people will face collateral consequences like losing their job, housing, or custody of their children because of unnecessary incarceration. This will affect thousands of people right away.

A framework for reform in Connecticut

Connecticut should adopt these core components to reform probation and parole and address overly punitive responses to violations of supervision:

- Restrict the use of incarceration for verified noncriminal (“technical”) violations. Incarceration should be eliminated as a sanction for many noncriminal violations.30 Instead, when a violation is confirmed, more moderate consequences can result, like suspension of earned time credit (explained below) or a shorter capped period of incarceration proportionate to the seriousness of the violation.

- Eliminate automatic detention for noncriminal “technical” violations. Instead, people accused of most noncriminal violations — like being late to an appointment with a parole or probation officer — should be issued a written notice with a date to appear in court if deemed necessary.

- Apply earned time credit to supervision sentences. As a reward for a given period of compliance, people should be credited with time off of their period of supervision. Earned time incentivizes continued success under supervision and reduces caseloads, allowing probation and parole staff to focus on people who have the greatest needs.

- Bolster due process. Additional steps for reinforcing due process include speeding up the time from initial hearing to final disposition, providing more neutral public locations for revocation hearings, and guaranteeing the right to counsel during hearings.

Examples from other states: New York’s Less Is More Act

Until Less Is More legislation was passed in September 2021, New York held the distinction of imprisoning people for noncriminal violations of parole at more than six times the national average. And in 2019, Black people in New York were five times more likely than white people — while Latino people were 30 percent more likely — to be re-incarcerated for a noncriminal parole violation.

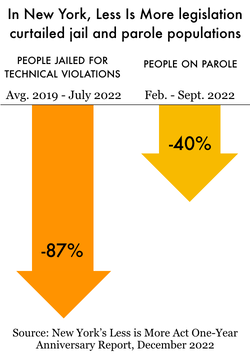

The impact of Less Is More was immediate. In late 2021, the smaller anticipated prison population — because fewer people would automatically be re-incarcerated for noncriminal violations — was a factor in the state’s decision to close six New York prisons. By the end of January 2022, even before most of the law’s provisions took effect, Less Is More had already led to sweeping measurable changes that affected New Yorkers dramatically: nearly 2,000 people on parole who had been incarcerated for noncriminal technical violations were released from jails and prisons. By March 2023, more than 17,000 eligible people in New York had been discharged early from parole, cutting the number of people on parole statewide by nearly 40%.

Overall, by reducing the use of incarceration as a response to noncriminal technical violations, Less Is More significantly helps people maintain and keep building on the progress they make during the reentry process, like securing employment and housing. Specifically, fewer people in New York are locked up for violations now and are no longer automatically brought into custody for most noncriminal violations (circumventing problems related to bail, among other consequences). And when they are detained while awaiting a revocation hearing, it’s not for nearly as long (a maximum of 55 days if they had not previously been detained, and 35 days if they were).

For years, state law was particularly harsh for people on parole, sending tens of thousands of New Yorkers back to jail or prison for minor noncriminal infractions and thwarting their momentum toward stability. But in just one year, Less Is More had an outsize impact on communities that are perpetually affected by mass supervision, in part because incarceration is costly and unnecessary for many people trying to rebuild their lives and livelihoods. Connecticut could move immediately to make similar changes to its community supervision programs and practices.

A fairer, less costly approach can protect Connecticut communities from unjust incarceration.

On any given day, Connecticut’s prisons are filled with people who are there because of supervision violations, at great cost to their loved ones and other taxpayers. In New York, Less Is More was envisioned and passed at a critical time, when nearly 34,000 people were on parole and the state led the nation in incarceration for noncriminal parole violations. Connecticut may not be a chart-topper in those ways, but as a proven leader in reforming its criminal legal system, the state can continue to have a meaningful impact on its people by adopting the provisions that New York State adopted.

The rest of the country can already look to Connecticut for major systems change: In 2021, it was the first state to make prison phone calls free for incarcerated adults and youth. That year, Connecticut took legislative steps toward ending prison gerrymandering, declaring that incarcerated people should be counted at home — and not where they are incarcerated — for redistricting purposes. In 2010, it was the sixth state to “ban the box,” improving employment opportunities for people with criminal records. And in 2005, Connecticut was the first to eliminate the crack/powder cocaine disparity of drug sentencing laws. Given that the state led in these areas of reform, reducing harm and incarceration by tackling supervision violations is a logical next step. Although in New York the Less Is More Act applies only to people on parole and not probation, Connecticut lawmakers and advocates should seize the opportunity to make the greatest impact possible by addressing the ways that both systems ensnare people in cycles of incarceration and surveillance.

Conclusions

Probation and parole are important tools for keeping people out of jails and prisons — and could even be helpful systems for connecting people with the community-based supports and services they’ve needed. Connecticut has numerous policy options — including New York State’s Less Is More approach — for modifying and scaling back supervision systems, focusing on people who have the greatest needs while steering clear of unreasonable conditions, fees, and other punishments. Only with serious, thorough reforms can supervision be a pathway out of and away from the carceral system in Connecticut.

Footnotes

Using the U.S. Census Bureau’s estimate of the Connecticut population (3,623,355) in 2021 and the Connecticut Judicial Branch’s January 2023 probation data, we calculated that roughly 0.85% of the state’s residents were on probation. ↩

The probation population in Connecticut used to be even larger: In July 2009, more than 56,000 people were under probation supervision. At that time, three times as many people were on probation as behind bars (fewer than 19,000 people were incarcerated in 2009, according to the Department of Correction). The probation population shrank by 41% from 2010 to 2020, a more drastic reduction than the United States’ 25% decrease in the probation population during those years. The overall decline may have been due in part to decreases in crime (particularly “violent” and property-related crime) and arrests. After crime increased in 2020, the state “resumed its decade-long drop in crime” in 2021. ↩

State analysts in Connecticut have not yet offered an explanation for the rise in probation caseloads in late 2021 and into 2022, but many jail and prison populations nationwide returned to pre-Covid-19 levels after the first months of the pandemic, in part because of related policy rollbacks and resumed court activities. These returns to pre-Covid operations undoubtedly led to the increase in probation populations in 2021. ↩

According to the Connecticut Criminal Justice Policy & Planning Division’s Monthly Indicators reports, in the last three months of 2022, 1,369 to 1,586 people each month began a probation-only sentence and 235 to 253 people began the probation portion of a split sentence (“split” between incarceration and probation). Meanwhile, 1,101 to 1,305 people finished their probation (called “Completion of Court Imposed Sanction”) during the same months, and 23 to 37 went to prison for a violation of probation (see November, December and January Monthly Indicators reports for full data). ↩

For the full statute, see Conn. Gen Stats S53a-30, “Conditions of probation and conditional discharge.” ↩

There are two primary types of electronic monitoring devices: One uses GPS technology to capture real-time location data, and another uses radio frequency technology to act as a “tether” with a preset limit, typically a given distance from someone’s home. People on probation in Connecticut may be on either, although only GPS devices are used for people under parole supervision, per correspondence with a program manager in the DOC’s Parole and Community Services Division. ↩

A 2022 ACLU report details the harms of electronic monitoring. A few examples: People with disabilities may struggle to understand and comply with EM requirements or to physically adjust or remove ankle monitors. Anyone who faces time and travel restrictions may not be able to do important errands and other activities or attend to medical needs. And entire households may be subjected to unannounced searches by law enforcement. ↩

According to the Connecticut Judicial Branch Court Support Services Division, which provided electronic monitoring data to Prison Policy Initiative by email on September 7, 2022, 343 people on adult probation were subject to either GPS or radio frequency monitoring as of the first week of July 2022, representing 1% of the 30,122 people on probation at that time. ↩

According to the Connecticut Judicial Branch, the state issued 5,585 “violation of probation” arrest warrants from July 2021 through June 2022, an average of 465 per month. ↩

Research shows that any form of contact with the criminal legal system, including arrest, has both physical and mental health consequences. Witnessing someone else’s arrest is also known to be a traumatic experience, particularly for children. ↩

Revocation refers to a person having their probation or parole revoked, or taken away, and being ordered to serve a different punishment, typically involving jail or prison time. ↩

In a request for information sent to the Connecticut Judicial Branch (response received in March 2023), we were informed that the average bond amount set by the courts for an alleged probation violation in Connecticut between July 1, 2021 and June 30, 2022 was $31,836.62. This amount is one-third of the median household income for a white family in Connecticut in 2021, and more than half of the median household income for a Latino family, according to the U.S. Census Bureau 2021 American Community Survey estimates. Data were not available for non-Latino Black and other race households. ↩

For example, in July 2022, the Connecticut Mirror profiled a man in this position who turned himself in for a noncriminal violation of his probation, not expecting to have to post bail. Suddenly facing a $45,000 bond he could not afford, he was incarcerated for almost two months before family members pooled money together to pay a bail bondsman so he could be released. ↩

According to a Yale Law School report examining parole revocation processes, people who were incarcerated for an alleged parole violation in 2016 remained in custody for an average of 15 weeks at a cost of approximately $14,500. Adjusting for inflation, that weekly cost of $967 in 2016 is about $1,231 per week in 2023. ↩

As with probation, all of the pitfalls of parole supervision and revocation disproportionately impact Black and Latino people. For example, in 2021, nearly half of the people facing alleged parole violations were Black (48%) — though they make up roughly 13% of the population in Connecticut — and 26% Latino, compared to 18% overall statewide. See Chart 3: 2021 Race & Gender Data for Connecticut parole violation data; see U.S. Census Bureau population estimates for state-level demographic data. ↩

Connecticut has other types of parole supervision that are not included in the table but are worth mentioning, primarily because they come up in various data sets and resources, though they’re small. For example, as of January 1, 2023, 91 people were on “DUI home confinement.” As the program name suggests, they were serving a sentence of home confinement as a result of a charge of driving under the influence. At the same time, 52 incarcerated people were temporarily in the community on a furlough, that is, having been granted permission to leave prison to attend a medical appointment, job interview, funeral, or “for any compelling reason consistent with rehabilitation.” A furlough can last up to 45 days; although people have not been permanently released during that period, they are technically supervised by DOC parole officers. ↩

For the full dataset, see the January 2023 Monthly Indicators of the Connecticut Office of Policy Management’s Criminal Justice Policy & Planning Division. ↩

This mostly refers to people who have short sentences: Typically, only those sentenced to more than two years of incarceration in Connecticut are eligible for parole consideration. People convicted of parole-ineligible offenses like murder, felony murder, and aggravated sexual assault are not eligible for transitional placement either. ↩

The state’s Criminal Justice Policy and Planning Division first published early discharge data, broken out by parole type, in the August 2022 edition of its Monthly Indicators report, reporting that 1,210 early discharges from special parole and discretionary parole had taken place between January 1, 2020 and August 1, 2022. ↩

Of the 1,050 people on special parole in the community on January 1, 2023 (not including those in halfway houses, for whom demographic data is not available), 40% were Black and 33% were Latino. This means that special parole is dramatically out of line with the state’s population, which was 13% Black and 18% Latino in 2021, according to Census Bureau data. ↩

From August 2021 through July 2022, Connecticut made 1,316 remands to custody, an average of 110 per month. Remands during that period accounted for 8.8% of total admissions, which also included people beginning new sentences of incarceration and those admitted for violations of probation. But omitting pretrial admissions, remands made up 29% to 50% of monthly admissions, with an average of 36%. It is important to underscore that because Connecticut has a unified jail and prison system, pretrial admissions are reflected in statewide data and not on the county level as they are in most states. Remand and admissions data are available in the Connecticut Criminal Justice Policy & Planning Division’s Monthly Indicators reports. ↩

According to data from the Connecticut Board of Pardons and Paroles, 228 absconding violations (failure to check in) and 211 other noncriminal violations went through the preliminary hearing process in 2021, out of 888 alleged violations. ↩

A person facing parole recission may have violated parole by receiving a disciplinary report while still incarcerated or by otherwise violating conditions set by the Board of Pardons and Paroles. Rescission means “the act of rescinding” and refers to people who have been granted parole but haven’t been released yet. ↩

According to the Fines and Fees Justice Center (FFJC), Connecticut is one of only a handful of states whose statutes are silent on the issue of parole supervision fees. This means that the state most likely does not charge any flat or monthly fee to people on parole supervision, though FFJC queried parole administrators in Connecticut for its 2022 report and received no reply. ↩

Although state law allows courts to collect daily fees for people wearing electronic monitoring devices, courts do not impose such fees, according to email correspondence with a representative of the Connecticut Judicial Branch Court Services Support Division on September 9, 2022. ↩

According to Conn. Gen. Stats S18-85a, the “prison debt law,” the state has a claim against each incarcerated person for the cost of their incarceration, participation in certain programs, and services like medical and dental visits. This law allows the state to come after assets like pensions, inheritance money, and insurance payouts to cover those costs. In 2022, Connecticut lawmakers did not take action on a bill that would have repealed the prison debt law, but a provision in the state budget that year limited the state’s ability to charge for time spent behind bars, allowing most people to retain up to $50,000 in assets before facing this. ↩

Since the Connecticut Criminal Justice Policy & Planning Division began regularly publishing early termination data in September 2022, an average of nine people per month have been recorded as receiving an early termination from discretionary parole. The most recent report, from March 2023, shows that five people in December 2022, four people in January 2023, and just three people in February were granted early termination from discretionary parole. Meanwhile, 16 people in December 2022, seven people in January 2023, and four people in February 2023 were approved for early termination from special parole (see “Other BOPP Actions,” page 4). ↩

This estimate is based on data from the Connecticut Judicial Branch: In 2014, the latest available year for data, 40% of adults on probation were rearrested within 24 months of beginning probation. And as of mid-2021, roughly half of all arrest warrants for violations of probation — including active warrants, issued warrants, and served warrants — were for non-felony charges. One-half of the current probation population is about 15,000 people; 40% of that number translates into a reduction of an estimated 6,000 arrests. ↩

The state’s open data sets “Accused Pre-Trial Inmates in Correctional Facilities” and “Sentenced Inmates in Correctional Facilities” show that as of January 1, 2023, 353 people of 3,591 who were incarcerated pretrial were accused of violating probation or another form of conditional discharge; 657 of 6,111 people had been sentenced for the same “offense.” ↩

In New York, the Less Is More Act prohibits incarceration for most noncriminal violations, but not all of them: For example, the violations of refusing a home visit or a search by a parole officer — or having a firearm without permission — are still eligible for incarceration as a penalty. ↩

Acknowledgements

The Prison Policy Initiative thanks our partners at the Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice for their insight and strategic guidance in producing this report. The author also thanks Wendy Sawyer for her support throughout the writing process. Finally, the organization thanks the individuals across the country who support our work, without whom this report would not have been possible.

Katal extends our deep gratitude and thanks to our partners at the Prison Policy Initiative — this report wouldn’t exist but for their dedicated efforts. We thank our members and volunteers for fighting — every day — for a more fair and just Connecticut. Thanks to Yonah Zeitz for the behind-the-scenes work to bring this report into the world and to Kenyatta Muzzanni for getting it started. We thank our editor, Jules Verdone, and our designer, Erica Asinas, for their attention to detail and production. And we thank our individual donors and foundation supporters who make our work possible.

About the authors

Leah Wang is a Research Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. She is the author of the recent report Punishment beyond prisons: incarceration and supervision by state, and of the organization’s report Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons. Her other work includes reports on diversion programs, how incarceration affects people’s experiences in the job market, and the importance of family contact for incarcerated people.

gabriel sayegh is the cofounder and co–executive director of the Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice. A community organizer and strategist for more than 20 years, gabriel has contributed to a wide range of collaborative grassroots movement efforts as a trainer, facilitator, and partner. He has developed and led campaigns to roll back the Rockefeller drug laws, prevent overdose deaths, end racially biased marijuana arrests, close the Rikers Island jail complex, pass bail reform, and more.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is known for its visual breakdown of mass incarceration in the U.S., as well as its data-rich analyses of how U.S. states vary in their use of punishment. Alongside reports like these, the organization leads the nation’s fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (a.k.a. prison gerrymandering) and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone industry and the video calling industry.

About the Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice

Katal is a community organization that works in Connecticut and New York to strengthen the people, policies, institutions, and movements that advance equity, health, and justice for everyone. We envision a world where all communities have the resources and power to exercise self-determination and participate meaningfully in the democratic process.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.