Grading the parole release systems of all 50 states

By Jorge Renaud

February 26, 2019

From arrest to sentencing, the process of sending someone to prison in America is full of rules and standards meant to guarantee fairness and predictability. An incredible amount of attention is given to the process, and rightly so. But in sharp contrast, the processes for releasing people from prison are relatively ignored by the public and by the law. State paroling systems vary so much that it is almost impossible to compare them.

Sixteen states have abolished or severely curtailed discretionary parole,1 and the remaining states range from having a system of presumptive parole — where when certain conditions are met, release on parole is guaranteed — to having policies and practices that make earning release almost impossible.

Parole systems should give every incarcerated person ample opportunity to earn release and have a fair, transparent process for deciding whether to grant it. A growing number of organizations and academics have called for states to adopt policies that would ensure consistency and fairness in how they identify who should receive parole, when those individuals should be reviewed and released, and what parole conditions should be attached to those individuals. In this report, I take the best of those suggestions, assign them point values, and grade the parole systems of each state.

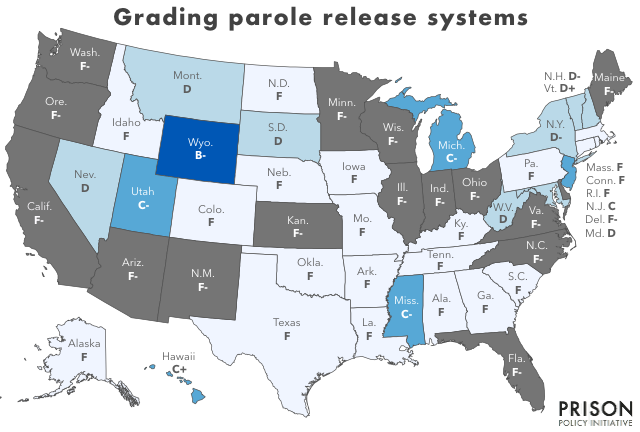

Sadly, most states show lots of room for improvement. Only one state gets a B, five states get Cs, eight states get Ds, and the rest either get an F or an F-.

| State | Grade | State | Grade | State | Grade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | F | Louisiana | F | Ohio | F- | ||

| Alaska | F | Maine | F- | Oklahoma | F | ||

| Arizona | F- | Maryland | D | Oregon | F- | ||

| Arkansas | F | Massachusetts | F | Pennsylvania | F | ||

| California | F- | Michigan | C- | Rhode Island | F | ||

| Colorado | F | Minnesota | F- | South Carolina | F | ||

| Connecticut | F | Mississippi | C- | South Dakota | D | ||

| Delaware | F- | Missouri | F | Tennessee | F | ||

| Florida | F- | Montana | D | Texas | F | ||

| Georgia | F | Nebraska | F | Utah | C- | ||

| Hawaii | C+ | Nevada | D | Vermont | D+ | ||

| Idaho | F | New Hampshire | D- | Virginia | F- | ||

| Illinois | F- | New Jersey | C | Washington | F- | ||

| Indiana | F- | New Mexico | F- | West Virginia | D | ||

| Iowa | F | New York | D- | Wisconsin | F- | ||

| Kansas | F- | North Carolina | F- | Wyoming | B- | ||

| Kentucky | F | North Dakota | F |

| State | Grade | State | Grade | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | F | Montana | D | |

| Alaska | F | Nebraska | F | |

| Arizona | F- | Nevada | D | |

| Arkansas | F | New Hampshire | D- | |

| California | F- | New Jersey | C | |

| Colorado | F | New Mexico | F- | |

| Connecticut | F | New York | D- | |

| Delaware | F- | North Carolina | F- | |

| Florida | F- | North Dakota | F | |

| Georgia | F | Ohio | F- | |

| Hawaii | C+ | Oklahoma | F | |

| Idaho | F | Oregon | F- | |

| Illinois | F- | Pennsylvania | F | |

| Indiana | F- | Rhode Island | F | |

| Iowa | F | South Carolina | F | |

| Kansas | F- | South Dakota | D | |

| Kentucky | F | Tennessee | F | |

| Louisiana | F | Texas | F | |

| Maine | F- | Utah | C- | |

| Maryland | D | Vermont | D+ | |

| Massachusetts | F | Virginia | F- | |

| Michigan | C- | Washington | F- | |

| Minnesota | F- | West Virginia | D | |

| Mississippi | C- | Wisconsin | F- | |

| Missouri | F | Wyoming | B- |

For the details of each state’s score see Appendix A. The sixteen states with an F- made changes to their laws that largely eliminated, for people sentenced today, the ability to earn release through discretionary parole. For more on these states, see the methodology.

How we graded and what distinguishes a fair and equitable parole system.

To assess the fairness and equity of each state’s parole system, we looked at five general factors:

- Whether a state’s legislature allows the parole board to offer discretionary parole to most people sentenced today; (20 pts.) ⤵

- The opportunity for the person seeking parole to meet face-to-face with the board members and other factors about witnesses and testimony; (30 pts.) ⤵

- The principles by which the parole board makes its decisions; (30 pts.) ⤵

- The degree to which staff help every incarcerated person prepare for their parole hearing; (20 pts.) ⤵

- The degree to which the parole board is transparent in the way it incorporates evidence-based tools. (20 pts.) ⤵

In addition, we recognize that some states have unique policies and practices that help or hinder the success of people who have been released on parole. We gave and deducted up to 20 points for these policies and practices. For example, we gave or deducted some points for:

| Helpful factors | Harmful factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Does not prohibit individuals on parole from associating with each other or with anyone with a criminal history (5 pts.); | Explicitly prohibiting individuals on parole from associating with others under supervision, or with anyone who has a criminal record (5 pts.) | |

| Capping how long someone can be on parole (5 pts.) or allowing individuals to earn “good time” credits that they can apply toward shortening their time on supervision (5 pts.) | Allowing the board to extend the period of supervision past the actual end of the imposed sentence (5 pts.) | |

| Does not require supervision or drug-testing fees. (5 pts.) | Requiring individuals on parole to pay supervision or drug-testing fees (5 pts.) |

Does the state’s sentencing structure empower a parole board to review people for possible release on discretionary parole? (20 pts.)

Parole boards can only review individuals who the legislature (and sometimes judges) say they can. Sixteen states passed laws effectively denying the possibility of parole for almost everyone committing crimes after those laws went into effect. To be sure, many of the remaining 34 states deny parole for individuals committed of certain crimes, but still offer discretionary parole to the majority of incarcerated individuals at some point in their sentence. Those 34 states all received 20 points. The states that have abolished discretionary parole received zero points and their procedures (for people convicted under the old law) were not evaluated further.

Parole hearings: Who gets a seat at the table? (30 pts.)

Unlike what happens in the movies, most parole hearings don’t consist of a few stern parole board members and one sweating, nervous incarcerated person. Most states don’t have face-to-face hearings at all, and instead do things like send a staff person to interview the prospective parolee. The staff person then sends a report to the voting members, who each vote (perhaps in isolation), and the incarcerated individual never has a chance to present their case or present their parole plans to the voting members, or perhaps to speak to their crime, or to rebut any wrong information the board may have. On the other hand, most states, by legislative mandate, give prosecutors and crime survivors a voice in the process. I have five metrics by which I rate whether or not a state has robust practices when it comes to parole hearings.

- The board should mandate face-to-face parole hearings. (15 pts.) Few people would hire someone, or rent a room to someone, or buy a house from someone without first sitting down and having a conversation. A person seeking freedom deserves to sit down and face those who will deny or approve that freedom. The voting members should see and speak to the person to whom they are granting or denying freedom. (And by see, we don’t mean via phone or video conferencing.2)

- There should exist a process by which someone seeking release can challenge incorrect information that the board may use to deny parole. (6 pts.) A parole decision is often based on information provided by outside law enforcement agencies, or by prison gang intelligence officers, and that may be wrong or outdated. It is important that there be an opportunity to make the parole board’s decision more accurate.

- Prosecutors should not be permitted to weigh in on the parole process. (3 pts.) Their voices belong in the courtroom when the original offense is litigated. Decisions based on someone’s transformation or current goals should not be contaminated by outdated information that was the basis for the underlying conviction or plea bargain.

- Survivors of violent crimes should not be allowed to be a part of the parole-decision process. (3 pts.) The parole process should be about judging transformation, but survivors have little evidence as to whether an individual has changed, having not seen them for years. A truly restorative collaboration would ask survivors of crime for their help in crafting transformative, in-prison programming for individuals convicted of violent crimes, but would not allow their testimony to influence parole decisions.

- Supportive testimony should be encouraged. (3 pts.) Anyone who has had a day-to-day interaction with the incarcerated person and anyone who intends to offer tangible support to the person seeking parole should be allowed to testify in person. It is obvious that a person with a substance abuse problem would benefit from a ride to AA meetings and why a parole board would benefit from an in-person inquiry into that volunteer’s dedication. On the other hand, many states have rules that prohibit correctional staff — who are often the only people who have had day-to-day contact with the incarcerated person and can speak to their behavior and to their recent on-the-job performance — from testifying at parole hearings.

Parole principles: Who is eligible for parole and are they treated fairly? (30 pts.)

Certain principles should be present in a fair parole system. Do all incarcerated individuals have a chance to earn parole? Do they understand what is expected of them? If they fulfill all the criteria expected of them, does the parole board grant parole or deny parole for other, more subjective reasons? And if the board denies parole, how often are individuals reviewed again? I graded states on the extent to which their parole systems reflect those principles.

- Every individual in prison should be eligible for parole. (12 pts.) In 16 states the pool of individuals eligible for parole is rapidly diminishing because state legislatures have stripped their parole boards of the power to grant release but to a dwindling number of individuals sentenced decades ago. Many other states have Truth in Sentencing statutes in place, which means individuals are not eligible for parole until they have almost completed their sentences. And at least six states have almost a quarter of their incarcerated population serving life without parole, or sentences so long that they amount to virtual life.

- Each state should have presumptive parole. (9 pts.) This policy gives every incarcerated person a list of specific things they must do to make parole, all but guaranteeing their release at a predetermined date if they fulfill the state’s requirements. This would inject fairness into the system and allow incarcerated persons and their families to better prepare for release.

- Parole board members should not use subjective criteria to deny parole. (6 pts.) Some boards and members base their decisions on criteria so subjective it is unlikely two people would agree on whether those criteria have been met. In addition, parole denials are often based on static factors that can never be changed or are beyond the control of the incarcerated individual. The most common reason for denial is a version of “serious nature of the offense,” which will always retain the same nature and is simply a way for the board members to say, “Come back next time.” All too often, parole boards will review an incarcerated person who has satisfied all of the typical requirements to be released and then denies that person for subjective or static factors. Such denials send the harmful message that the parole board neither recognizes nor rewards transformation.

- No more than a year should elapse between a parole denial and a subsequent review. (3 pts.) Some states, such as Texas, allow up to ten years to elapse between reviews. A parole denial by the board in a robust system should only be based on factors such as non-participation in required programming or recent disciplinary infractions. A year is more than sufficient for the incarcerated individual to address reasonable, objective, denials like these.3

Preparation: If you get one shot at freedom, shouldn’t the state help you get ready? (20 pts.)

A parole hearing could be someone’s only shot at freedom for years. If they don’t know what programs the board expects them to take, or what information they may have to challenge, and if they can’t prove to the board they have possible employment and a place to stay, the board isn’t going to let them go. Preparation matters, and I suggest two metrics to judge states by how well they help people prepare for their parole hearings:

- Departments of Corrections should provide case managers to each person within six months of their arrival in prison. (10 pts.) These case managers would help inform incarcerated persons what programs they needed to take, work with those persons to prepare for the hearing itself, and connect them to outside agencies after parole was granted.

- Every incarcerated person should have access to any documents or records the parole board relies on to make its decision. (10 pts.) Parole boards make their decisions based on a person’s criminal history and current offense, and every incarcerated person should be able to speak to both in the presence of the board.

Transparency: Can the public understand the parole board’s decisions? (20 pts.)

One of the strongest critiques of state parole systems is that they operate in secret, making decisions that are inconsistent and bewildering. Neither the individuals being considered for parole nor the general public understand how parole boards decide who to release or who to incarcerate further. When parole systems reject people for arbitrary or capricious reasons, they unintentionally, but to devastating effect, tell incarcerated people that their transformation does not matter. And the public, who is paying for the criminal justice system, deserves to know how it works and how well it works.

Many states have begun to rely on parole guidelines and validated risk assessments as a way to step back from the entirely subjective decision-making processes they have been using. These instruments have their own deficiencies, but states that use them and provide the public access to that decision-making process were graded higher than states that refuse to pull back the parole-decision curtain.

Transparency can be measured in three ways:

- Parole boards should have guidelines to help them make unbiased parole decisions, and those guidelines should be shared with the public. (8 pts.) Fair processes don’t thrive in the dark. More parole boards have turned to parole guidelines and validated risk assessments as a way to move away from “gut decisions,” and as a way to give themselves more cover for difficult political decisions. Some states will create their own instruments from scratch, without having them validated scientifically for bias, and the public deserves to know what criteria is being used to release people into their community, or to deny community members their freedom.

- Parole boards should issue yearly, public reports that explain deviations from outcomes recommended by parole guidelines. (6 pts.) Institutions with oversight over parole boards should receive reports detailing release rates and their deviations from recommended guidelines and assessments. While parole boards are still expected to exercise personal discretion — otherwise, all parole decisions could be made by a computer — parole boards should be required to publicly explain why they might be consistently denying release when published guidelines recommend release.

- Individuals who are denied parole and fit all the requirements should be able to appeal a denial and get either a rehearing or a credible explanation for that denial based on objective factors. (6 pts.) Every state seems to have a version of a statute that claims, “Parole is not a right; it is a privilege.” However, incarcerated individuals should have a reasonable expectation that they will be released if they are eligible for parole, if they have completed all required programming, if they have no major disciplinary infractions, and if they have housing and employment waiting for them.

Methodology

This report relies heavily on the publications of the Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Minnesota, which centralize many important details about parole eligibility, hearings, and post-release policies and conditions.

Our list of 16 states that have abolished discretionary parole is based on the Robina Institute’s classification of states as having either largely a determinate — without discretionary parole — or indeterminate — with discretionary parole — system. (See sidebar)

Our policy suggestions — and the relative point values — are our own, but the data for 27 of the states is based on the Robina Institute’s excellent series Profiles in Parole Release and Revocation: Examining the Legal Framework in the United States.5 For the seven states with indeterminate sentencing systems that the Robina Institute has not published profiles for (Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, Tennessee, South Carolina, South Dakota, and West Virginia), Prison Policy Initiative volunteers Eva Kettler, Sari Kisilevsky, Joshua Herman, Simone Price, Tayla Smith and I delved into statutes and parole board policies to collect the necessary data. The sourcing for each state is in Appendix A. Additional data about how these policies are reflected in grant rates, technical violaton rates and other outcome metrics are available in the appendix to my earlier report Eight Keys to Mercy: How to shorten excessive prison sentences.

Our intent with the scoring was to make it possible to compare systems that are both very different and very complex in a way that will make sense across state lines. In particular, we tried to give factors that we felt were more important a greater weight. Other advocates — and some state leaders — may disagree with some of our findings of fact or with the weights that we gave to various factors that make up a fair and equitable parole system. We welcome new information and factual corrections, and encourage our readers with different ideas on how parole should work to publish alternative analyses with their own scoring systems.

Four of the sections require more comment:

- We believe that parole decisions should be made on objective criteria and that subjectivity should be prohibited. The decision to release someone should be based on a number of factors — participation in educational and vocational programs, in-prison disciplinary history, and other verifiable metrics that indicate personal transformation. All too often, denials for subjective reasons like the “gravity of the offense” or whether the release will “lessen the seriousness of the offense” serve only to diminish the motivation necessary for change. Unfortunately, only Michigan gets full credit for explicitly prohibiting subjectivity, and 16 states earned zero points because their statutes specifically list examples of subjective excuses to deny parole. For this reason, we gave partial credit to 17 states whose statutes refrained from encouraging denials for subjective reasons.

- We believe that prosecutors should not be allowed to weigh in on parole decisions. No states prohibit prosecutorial input, so we gave our highest score here — three points — to those states whose statutes were silent on this matter. We gave two points to states that alerted prosecutors only after parole had been granted. States that allowed input from prosecutors (usually also requiring that the prosecutor ask or register for notification of a parole hearing) received one point, and zero points were given to states that mandated prosecutors be notified before all parole hearings.

- We believe that every incarcerated person should be given an opportunity to be paroled, so we gave points to states by the share of their prison population that was eligible in 2016 for release on parole. This is an important factor because it demonstrates how many people are statutorily eligible to be released. This is also an imperfect measure, for several reasons. Some states do not report the necessary data; the existing data does not reflect how many people will never be statutorily eligible to be considered for release, and in addition, existing parole policies could influence this figure. For example, a parole board that refuses to release people would create a higher percentage of individuals eligible for release, and a parole board that released almost everyone at the first opportunity would have a lower percentage of incarcerated individuals eligible for release. To our knowledge, there is not yet a multi-state comparable way to determine: of the people sent to prison in a given year, how many of those will be considered for release before their maximum release date? And of those people, how many will be eligible for consideration significantly6 earlier than their maximum release date?

- We believe that transparency requires parole boards to produce annual reports to the public and the legislature that include statistics on parole denials and justifications for those denials, particularly when those denials contradict any guidelines given to the parole board. Because all parole boards issue reports, we gave the full 6 points to 13 states that require the parole board to publish reports with enough detail for the legislature to hold the board accountable, and zero points to all other states.

We also gave extra credit — and sometimes took away points — for post-release policies. All too often, states that offer programs to incarcerated individuals to help them succeed then allow that work to be undone by harmful post-release policies.7 State parole authorities returned to incarceration approximately 60,000 individuals on parole for technical violations in 2016 without those individuals committing a new offense.8 The conditions placed on those leaving prison are rarely in and of themselves violations of law. If an individual on parole leaves the county without permission, buys a car without telling a parole official, or tests positive for drugs, those behaviors should be dealt with through collaboration between parole officials and community agencies. At no time should a non-criminal violation subject someone on parole to re-incarceration.

I thought three post-release conditions were worthy of singling out:

- Prohibiting an individual from associating with someone on parole or who has a criminal record;⤵

- Limiting how long someone can be on parole, or conversely, imposing additional time past what the original sentence called for; and⤵

- Imposing supervision, drug testing, or electronic monitoring fees.⤵

Re: association. This prohibition is based on a belief that merely being in the company of another person on parole — or who has a criminal record, regardless of how long ago the actual crime occurred — will invite criminal behavior. This policy ignores the widely-accepted idea that the mentorship and guidance of someone who has gone through a negative experience — be it incarceration, cancer, divorce, substance abuse, the death of a spouse or child — is affirming and positive. Lastly, denying those leaving prison the right to associate with others like them ignores the powerful impact on local, state, and national criminal justice policy reform by groups of formerly incarcerated individuals, many of whom are on parole, all of whom have criminal histories.

Re: time limits. I gave points to states that provide one or more mechanisms to shorten parole because there is no evidence that unending supervision results in anything other than higher recidivism rates. (Recall that currently people are rarely granted parole unless they are deemed a low risk of committing another crime.) Meaningful supervision when someone first leaves prison can be positive, if it is not overly restrictive and goal-oriented instead of sanction-oriented.9 However, many states issue a boiler-plate set of conditions that are not tailored to individual needs, and thus do not contribute to successful reentry. As Massachusetts officials readily admit, “by virtue of being under supervision in the community, an inmate may have a higher likelihood of re-incarceration.” Shockingly, a few states even give parole boards the power to extend supervision past the end of the imposed sentence10 — a devastating policy with dubious legality.

Re: fees. Finally, very few individuals have the economic means to comply with the array of fees that some states impose. While these states usually claim to waive fees depending on the released individual’s capacity to pay, in truth, parole officials pressure newly released people to pay as much and as quickly as possible and threaten to impose sanctions otherwise. That ignores two truths:

- Almost no one leaving prison has assets, wealth, or savings.

- Many individuals leaving prison have other financial obligations, including child support, restitution, and unpaid fines.

Individuals should not bear the cost of their incarceration. Supervision is simply an extension of that cost.

To be sure, some states have quirky11, mostly punitive, conditions of supervision that might warrant point deductions, but we choose not to do that because it was not possible to have a comprehensive review of these conditions that would allow for truly fair comparisons between states.

Acknowledgements

A report of this scope cannot be written without the help of others. I am deeply indebted to the Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Minnesota for their invaluable series on state parole polices which centralize many important details about parole eligibility, hearings, and post-release policies and conditions. Eva Kettler, Sari Kisilevsky, Joshua Herman, Simone Price, and Tayla Smith helped dig through parole policy and statutes to fill in details from states not yet covered by the Robina Institute and Mack Finkel prepared the analysis of the National Corrections Reporting Program data to show how many people in each state are currently eligible for parole hearings.

One challenge with writing a report like this is keeping it centered on the experience of people hoping for release on parole while also making sure that this report is relevant in all states, and to this end I am particularly thankful for the feedback of Laurie Jo Reynolds and Alex Friedmann who helped improve this report on a very short deadline.

Finally, I thank my Prison Policy Initiative colleagues for support and encouragement, especially Peter Wagner for patiently editing and helping me develop the scoring system and organize the state-by-state data in a form that will be useful to other advocates.

About the author

Jorge Renaud is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. He holds a Masters in Social Work from the University of Texas at Austin. His work and research is forever informed by the decades he spent in Texas prisons and his years as a community organizer in Texas, working with those most affected by incarceration. His most recent report was Eight Keys to Mercy: How to shorten excessive prison sentences (November 2018).

Footnotes

For example, Wisconsin changed its sentencing structure in 2000 to eliminate the option of discretionary parole for all offenses committed after that date. But in California and Washington, discretionary parole was eliminated for most offenses, although it is still available for life and certain other offense/sentencing types. Of course, the federal constitution did not allow states to remove parole for offenses committed prior to the law change, so some people are still reviewed for discretionary parole. For how discretionary parole release differences from the systems of "mandatory parole" used in many of those 16 states, see the methodology. ↩

The willingness of some states to interview applicants for parole via video may reduce costs at the expense of fairness. Judge Amiena Khan, the executive vice president of the National Association of Immigration Judges, said that videoconferencing “does not always paint a complete picture” of a detained immigrant, referring to the growing use of videoconferencing in detention hearings. The judge said “it’s more difficult to interact, to judge eye contact and nonverbal clues like body language.” While the judge was specifically referencing immigrants in detention, incarcerated individuals interviewed by video face the same barriers when trying to persuade a parole board to grant them parole, barriers that resulted in higher deportation rates for those whose cases were heard via video. See Goldbaum, Christina. “Videoconferencing in Immigration Court: High-Tech Solution or Rights Violation?” The New York Times. (Feb. 12, 2019.) ↩

We have seen certain states deny someone for parole but promise immediate release when a certain program is completed. This should happen more often. ↩

Unfortunately, the transparency of parole systems in those 16 states has declined since they abolished discretionary parole, though it's not clear if there is a causal connection. ↩

The profile for Alabama is not listed on that page (as of February 2019). You can find it on this page. ↩

We are not, at this time, proposing a specific measure. But it is important to distinguish the sentencing practices of states that give out sentences of 10 to 30 years with parole eligibility starting at the 10th year from the states that give out sentences that range from 20 to 21 years. ↩

For example, Nebraska granted parole to 87% of the individuals who were eligible for discretionary release in 2014, then turned around in 2016 and returned 416 individuals on parole to prison for technical violations without committing new offenses. ↩

Kaeble, D. “Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016.” Appendix Table 7, Adults exiting parole, by type of exit. U.S. Department of Justice. (April 2018.) ↩

“Supervision periods should have a relatively short maximum term limit — generally not exceeding two years — but should be able to terminate short of that cap when people under supervision have achieved the specific goals mapped out in their individualized case plans.” From “Toward an Approach to Community Corrections for the 21st Century.” Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management. Harvard Kennedy School. (July 2017.) ↩

See Arkansas Code Title 5. Criminal Offenses S 5-4-107. Extended supervision and monitoring for certain sex offenders. (b)(1). Kentucky Revised Statutes. Chapter 532-043 Requirement of postincarceration supervision of certain felonies. (1)(a). ↩

Alaska prohibits an individual on parole from changing residence without notification and considers an overnight stay a change of residence, punishable by parole revocation. Colorado specifically prohibits anyone under “criminal supervision” from attending a meeting at the Legislature that concerns the Parole Board. In Idaho, the risk assessment and parole guideline instruments are exempt from public disclosure. In Pennsylvania, all life sentences are Life Without Parole. On the other hand, Montana should be applauded for requiring that their parole board members have “expertise and knowledge of American Indian culture.” ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.