Separation by Bars and Miles:

Visitation in state prisons

By Bernadette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf

October 20, 2015

Press release

Leer en español

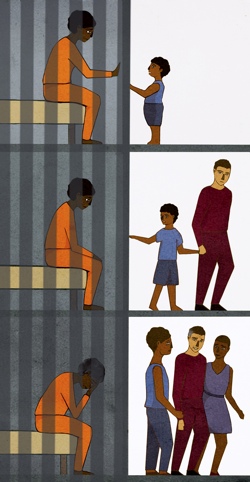

Most of today’s prisons were built in an era when the public safety strategy was to “lock ‘em up and throw away the key.” But now that there is growing interest from policymakers and the public to help incarcerated people succeed after release, policymakers must revisit the reality of the prison experience and the false assumptions of that earlier era.

Almost by definition, incarceration separates individuals from their families, but for decades this country has also placed unnecessary burdens on the family members left behind. Certainly in practice and perhaps by design, prisons are lonely places. Analyzing little-used government data,1 we find that visits are the exception rather than the rule. Less than a third of people in state prisons receive a visit from a loved one in a typical month:2

| Type/time frame | Percent receiving that contact |

|---|---|

| Personal visit in the past month | 31% |

| Phone in the past week | 70% |

Despite the breadth of research showing that visits and maintaining family ties are among the best ways to reduce recidivism,3 the reality of having a loved one behind bars is that visits are unnecessarily grueling and frustrating. As a comprehensive 50-state study on prison visitation policies found,4 the only constant in prison rules between states is their differences. North Carolina allows just one visit per week for no more than two hours while New York allows those in maximum security 365 days of visiting. Arkansas and Kentucky require prospective visitors to provide their social security numbers,5 and Arizona charges visitors a one-time $25 background check fee in order to visit. And some rules are inherently subjective such as Washington State’s ban on “excessive emotion,”6 leaving families’ visiting experience to the whims of individual officers. With all of these unnecessary barriers, state visitation policies and practices actively discourage family members from making the trip. The most humane and sensible government policies would instead be based on respect and encouragement for the families of incarcerated people.

Despite the breadth of research showing that visits and maintaining family ties are among the best ways to reduce recidivism,3 the reality of having a loved one behind bars is that visits are unnecessarily grueling and frustrating. As a comprehensive 50-state study on prison visitation policies found,4 the only constant in prison rules between states is their differences. North Carolina allows just one visit per week for no more than two hours while New York allows those in maximum security 365 days of visiting. Arkansas and Kentucky require prospective visitors to provide their social security numbers,5 and Arizona charges visitors a one-time $25 background check fee in order to visit. And some rules are inherently subjective such as Washington State’s ban on “excessive emotion,”6 leaving families’ visiting experience to the whims of individual officers. With all of these unnecessary barriers, state visitation policies and practices actively discourage family members from making the trip. The most humane and sensible government policies would instead be based on respect and encouragement for the families of incarcerated people.

Given the great distances families must travel to visit their incarcerated loved ones,7 it is inexcusable for states to make the visiting process unnecessarily stressful.8 Using the same dataset, we find that most people (63%) in state prison are locked up over 100 miles from their families,9 and unsurprisingly, distance from home is a strong predictor for whether a person in a state prison will receive a visit in a given month.

Locking people up far from home has the unfortunate but strong effect of discouraging visits. We found that among incarcerated people locked up less than 50 miles from home, half receive a visit in a month, but the portion receiving visits falls as the distance from home increases:

| Distance | Percent visited last month |

|---|---|

| Less than 50 miles | 49.6% |

| Between 50 and 100 miles | 40.0% |

| Between 101 and 500 miles | 25.9% |

| Between 501 and 1,000 miles | 14.5% |

And while there are a variety of reasons why an incarcerated person might not receive a visit, the fact that most prisons were built in isolated areas ensures hardship on the families of incarcerated people. Studies of incarcerated people in California, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, South Dakota, and Tennessee found that distance is a top barrier preventing them from in-person contact with their families.10

Millions of families are victims of mass incarceration, and policymakers are starting to understand that. Having established that large distances discourage visitation, this report makes several recommendations for how the U.S. criminal justice system can support — rather than punish — the families of incarcerated people. States should:

- Use prison time as an option of last resort.

Understanding how putting great distances between incarcerated people and their families is often damaging, states should implement alternatives to incarceration that can keep people home or closer to home11 such as Washington State’s Family and Offender Sentencing Act, which allows judges to waive prison time and instead impose community custody for some primary caregivers of minor children.12 At the same time, states’ criminal justice policies should match their rhetoric of decarceration. States such as California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, and Texas should recognize that they have been able to successfully reduce both imprisonment and crime13 and lead the rest of the nation by closing remote prisons. - Eliminate and refrain from adopting visitation policies that dehumanize families and actively encourage visitation.

States should recognize that incarceration is often an emotional and vulnerable time for families and should actively encourage visiting by making the prison environment as comfortable as possible. States such as California14 and Massachusetts15 should stop their unnecessary and dehumanizing strip and dog searches of visitors. States can enact family-friendly visitation programs such as the children’s center in New York State’s Bedford Hills Correctional Facility16 and Oakland Livingston Human Service Agency’s program in Michigan that allows incarcerated fathers to have several hour-long visits with their children with room for activities. In the short-term, states can make visits more comfortable for families with children by making crayons and coloring books available.17 - Willingly cooperate with the Federal Communications Commission’s upcoming prison and jail telephone regulations, and have the courage to reduce the costs to families even further. Stop making other forms of communication exploitative.

Fortunately, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is finally poised to end $1-per-minute phone calls from prisons and jails with its strong proposal18 to regulate local, intra-state, and inter-state calls as well as ancillary fees. The FCC will be encouraging states to view these rate caps as a federal ceiling. States can and should reduce the costs to families even further,19 and states such as Arkansas and Indiana should stop fighting the regulations.20 Further, states should avoid implementing video visitation as a replacement for in-person visits — as has been done in hundreds of local jails throughout the country — and avoid overly restrictive mail policies like those of the New Hampshire Department of Corrections that ban children’s drawings and greeting cards.21 - Listen to the recommendations of incarcerated people and their families who can best identify the obstacles preventing them from staying in touch during incarceration.22

Families have long been saying that no matter how much they would like to visit and see firsthand that their loved ones are safe, sometimes the money and time required make visiting incarcerated loved ones virtually impossible.23 The sad reality is that currently, a majority of incarcerated parents of minor children do not receive visits from any of their children during their prison sentence.24 Recognizing that their families are often the main source of hope for people during their incarceration and the main source of support upon release, correctional facilities should gather and seriously consider family input when making decisions about visitation and communication policies. - Implement programs that assist families who want to visit.

The costs of visitation and communication literally drive some families of incarcerated people into debt.25 States should consider implementing free transportation to prisons as the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision did before budget cutbacks in 2011. Departments of Corrections should also consider video visitation as a supplement to in-person visits,26 especially for remote prisons. The Oregon Department of Corrections first implemented video visitation as a supplement to traditional visits in its two most remote prisons,27 and it has since expanded the technology to prisons throughout the state. States can also easily model video visitation programs after that of the Mike Durfee State Prison in South Dakota where, for 12 hours every week, incarcerated people have access to free video visits using Skype.28 - When faced with prison overcrowding, explore sentencing and parole reforms instead of prison expansion and out-of-state transfers.

Often, when states are faced with prison overcrowding, they adopt band-aid fixes like sending people to out-of-state prisons where they will be even further from their families.29 More effective solutions are to first adopt low-hanging fruit reforms such as reducing the aging prison population or allowing primary caregivers to serve their sentences in the community, and then to explore larger-scale sentencing and parole reforms.

Appendix

Using the Bureau of Justice Statistics’s 2004 Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities, we found the breakdown of how far people in state prisons reported being locked up from their home communities. The table below provides estimated counts for the total U.S. state prison population based on the responses of the 14,500 people imprisoned in state prisons who responded to the BJS survey.

To get this data, we relied on the question: S7Q6c. How far from this prison is … where you were living at the time of your arrest? Is it less than 50 miles, between 50 miles and 100 miles, between 101 and 500 miles, between 501 and 1,000 miles, or more than 1,000 miles?

| Distance | Count | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 50 miles | 184,041 | 15.7% |

| Between 50 and 100 miles | 244,981 | 20.9% |

| Between 101 and 500 miles | 623,011 | 53.2% |

| Between 501 and 1,000 miles | 92,356 | 7.9% |

| More than 1,000 miles | 26,017 | 2.2% |

Methodology

The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects visitation and distance from home data periodically as a part of its Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities,30 but BJS does not routinely publish the results in a format that can be accessed without statistical software. The Bureau of Justice Statistics published data on how far incarcerated parents of minor children are from their children in Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children.31 We prepared this report to focus on people imprisoned in state prison in general.

This report relies on the Bureau of Justice Statistics survey from 2004, which is the newest available. The next survey32 is being conducted in 2015–2016 with the data to be available several years later. While 2004 is older than we would like, we know of no reason or trend that would make visitation data from the 2004 survey an unreliable reflection of visitation today, in 2015.

For this report, we used the Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities’s questions about the location of pre-incarceration homes as a proxy for where family and community ties are located. We used the following questions from the Survey:

- S7Q6c. How far from this prison is … where you were living at the time of your arrest? Is it less than 50 miles, between 50 miles and 100 miles, between 101 and 500 miles, between 501 and 1,000 miles, or more than 1,000 miles?

- S10Q7a. Are you allowed to talk on the telephone with friends and family?

- S10Q7b. In the past week, how many telephone calls have you made or received? Do not include calls to or from a lawyer.

- S10Q8a. In the past month, have you had any visits, not counting visits from lawyers?

- S10Q8c. Were you allowed to have any visits?

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Elydah Joyce for the illustrations depicting the emotional toll caused by incarceration.

Footnotes

We used data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2004 Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities. More information is available here: http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=dcdetail&iid=275. ↩

Our analysis is based on people who were permitted to talk on the phone and permitted to have visits in a given month. The survey we used did not include meetings with lawyers as “visits.” ↩

A rigorous Minnesota Department of Corrections study found that a single visit reduces recidivism by 13% for new crimes and 25% for technical violations, and an Ohio Department of Corrections study found that more visits were associated with fewer rule violations. See: Minnesota Department of Corrections, The Effects of Prison Visitation on Offender Recidivism (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Corrections, November 2011). Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: http://www.doc.state.mn.us/pages/files/large-files/Publications/11-11MNPrisonVisitationStudy.pdf. See also: Gary C. Mohr, An Overview of Research Findings in the Visitation, Offender Behavior Connection (Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, 2012). Accessed on October 16, 2015 from: http://www.asca.net/system/assets/attachments/5101/Mohr%20-%20OH%20DRC%20Visitation%20Research%20Summary.pdf?1352146798. ↩

The study focused on policy directives (detailed rules promulgated by correctional administrators), but there are two more layers that govern prison visitation not included in the study: administrative regulations (general grants of rulemaking authority to correctional administrators) and facility-specific rules (applicable to specific prisons and usually more detailed than policy directives yet not always comprehensive). See: Chesa Boudin, Trevor Stutz, and Aaron Littman, “Prison Visitation Policies: A Fifty State Survey” Yale Law & Policy Review Vol 32:149 (March 2014), 157-166. ↩

Requiring social security numbers can deter family members who are not legal citizens from visiting. ↩

See the visitor’s guidelines for Monroe Correctional Complex for an example: https://web.archive.org/web/20151010134317/http://www.doc.wa.gov/facilities/prison/mcc/docs/mccvisitguidelines.pdf. ↩

The practice of incarcerating people far from their families is is not an inevitable outcome of incarceration. States and the Bureau of Prisons could choose to place incarcerated people in prisons that are closer to their families. For example, New Jersey’s 2010 Strengthening Women and Families Act led to N.J. Rev. Stat. § 30:4-8.6 (2014), which requires that the Department of Corrections Commissioner make every effort to assign incarcerated women to the prisons closest to their families and Fla. Stat. § 944.171(4) (2015) states that, as much as possible, the department should consider the proximity of a prison to an incarcerated person’s family when making placements. See: New York Initiative for Children of Incarcerated Parents, “Fact Sheet: Proximity to Children when a Parent is Incarcerated,” The Osborne Association, 2013. Accessed on October 2, 2015 from: http://www.osborneny.org/images/uploads/printMedia/ProximityFactSheet_OA2013.pdf. Unfortunately, there has been a trend away from the Bureau of Prisons honoring judges’ recommendations on prison placements to ignoring these recommendations. The Bureau of Prisons should consider judges’ assessments of those who are sentenced and make its best attempt to honor recommendations to keep people closer to home. See: Federal Bureau of Prisons, Legal Resource Guide to the Federal Bureau of Prisons 2014 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2014), p 12. Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: https://www.bop.gov/resources/pdfs/legal_guide.pdf. See also: S. David Mitchell, “Impeding Reentry: Agency and Judicial Obstacles to Longer Halfway House Placements” Mich. J. Race & L. Vol 16:235 (2011). ↩

“Riding the Bus: Barriers to Prison Visitation and Family Management Services” describes the visiting experience for New York State families based on 200 hours of observation of family support group meetings, attendance at activities aimed at families of incarcerated people, and observation of five bus rides to two upstate New York prisons. See: Johnna Christian, “Riding the Bus: Barriers to Prison Visitation and Family Management Services” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice Vol 21:31 (February 2005). ↩

See Appendix. ↩

In a 2010 study by the Department of Health and Human Services, incarcerated fathers reported distance to the prison as the top barrier to contact. See: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Parenting from Prison: Innovative Programs to Support Incarcerated and Reentering Fathers (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 2010). Accessed on October 8, 2015 from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/parenting-prison-innovative-programs-support-incarcerated-reentering-fathers-0. See also a New York State-specific study: NYS Division of Criminal Justice Services, Children of Incarcerated Parents in New York State: A Data Analysis (Albany, NY: NYS Division of Criminal Justice Services, 2013). Accessed on August 18, 2015 from: http://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/pio/2013-children-with-inarcerated-parents-report.pdf. ↩

Criminologists William D. Bales and Daniel P. Mears found that visitation reduces and delays recidivism. As a result, they recommended placing incarcerated people close to their home communities as one low-cost policy option. See: William D. Bales and Daniel P. Mears, “Inmate Social Ties and the Transition to Society: Does Visitation Reduce Recidivism?” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency Vol 45:287 (2008), 315. A Minnesota Department of Corrections study recommended that if — as this report finds — there is a significant relationship between visitation and distance, states such as Minnesota should seriously consider distance from home when placing incarcerated people in particular prisons. See: Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2011, p 31. ↩

This is no doubt a positive reform, but states should go even further by expanding eligibility to include parents who might not have custody of their children. States should also consider allowing judges the discretion to impose community custody for people with past violent offenses. For more on Washington State’s Family and Offender Sentencing Alternative, see: https://www.doc.wa.gov/corrections/justice/sentencing/parenting-alternative.htm#fosa ↩

Public Safety Performance Project, “Most States Cut Imprisonment and Crime,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, November 10, 2014 from: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/multimedia/data-visualizations/2014/imprisonment-and-crime. See also: Lauren-Brooke Eisen and Inimai Chettiar, The Reverse Mass Incarceration Act (New York, NY: The Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, October 2015), p 10. Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/The_Reverse_Mass_Incarceration_Act%20.pdf. ↩

Paige St. John, “California steps up prison drug screening for visitors and staff,” Los Angeles Times, March 3, 2015. Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: http://www.latimes.com/local/political/la-me-ff-california-steps-up-prison-drug-screening-for-visitors-and-staff-20150303-story.html. ↩

Meghan E. Irons, “Prison visitors irate about plan for drug-sniffing dogs,” The Boston Globe, March 23, 2013. Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2013/03/22/visitors-could-soon-face-random-narcotics-dogs-sniff-state-prisons/BPTYlAFi6vuwghlfPM1GsN/story.html. ↩

For more information on New York State’s children’s centers, visit The Osborne Association website: http://www.osborneny.org/programs.cfm?programID=11. See also: Tanya Krupat, Elizabeth Gaynes, and Yali Lincroft, A Call to Action: Safeguarding New York’s Children of Incarcerated Parents (New York, NY: The New York Initiative for Children of Incarcerated Parents, The Osborne Association, 2011), p 33. Accessed on August 27, 2015 from: http://www.osborneny.org/NYCIP/ACalltoActionNYCIP.Osborne2011.pdf. ↩

Krupat, Gaynes, and Lincroft, 2011, p 34. ↩

Peter Wagner, “FCC commissioners reveal details of their proposal to protect all families of incarcerated people,” Prison Policy Initiative, October 1, 2015. Accessed on October 19, 2015 from: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2015/10/01/clyburn-proposal/. ↩

In 2013 New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision Acting Commissioner Anthony J. Annucci submitted a letter to the Federal Communications Commission explaining that when New York State eliminated the commission in its phone contract and substantially reduced the rate to families, the number of calls rose from 5.4 million calls in 2006 to over 14 million in 2013, it improved the relationship between the Department and “offender advocacy groups,” and it lowered the rate of illicit cell phone use. He called prison phone reform “among the most cost-effective family reunification options that we offer.” See: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/NYDOCCSletter.pdf. In total, the Federal Bureau of Prisons and ten states have banned commissions. See: https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/. ↩

Securus Technologies v. FCC (Docket No. 13-1280, D.C. Cir. 2015) ↩

Jeremy Blackman, “Prison tightens mail policy in effort to curb drug influx,” Concord Monitor, April 13, 2015. Accessed on April 30, 21015 from: http://www.concordmonitor.com/home/16462117-95/prison-tightens-mail-policy-in-effort-to-curb-drug-influx. States should also avoid letter ban policies, which — as our February 2013 report found — have been implemented in local jails across the country. Leah Sakala, Return to Sender: Postcard-only Mail Policies in Jails (Easthampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, February 7, 2013). Accessed on October 19, 2015 from: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/postcards/. ↩

For example, Echoes of Incarceration is an award-winning documentary initiative produced by youth with incarcerated parents. In their first film, four youth of incarcerated parents describe how their parents’ incarceration has impacted them: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r0HooqTwh_4&feature=youtu.be. ↩

It is especially difficult for incarcerated people and their families to afford the costs associated with visits because they are some of the poorest families in this country. Our report, Prisons of Poverty: Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned, found that, in 2014 dollars, incarcerated people had a median annual income of $19,185 prior to their incarceration, which is 41% less than non-incarcerated people of similar ages. See: Bernadette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf, Prisons of Poverty: Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned (Easthampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, July 9, 2015). Accessed on September 3, 2015 from: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/income.html. ↩

Based on the same dataset as this report, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that only 42% of parents of minor children imprisoned in state prison received a personal visit from their children since admission. Lauren E. Glaze and Laura M. Maruschak, Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children, (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics, August 2008), p 6. Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pptmc.pdf. ↩

A recent report found 34% of the families studied fell into debt from simply paying for phone calls and visits with their incarcerated loved ones. See: Saneta deVuono-powell, Chris Schweidler, Alicia Walters, and Azadeh Zohrabi, Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families (Oakland, CA: Ella Baker Center, Forward Together, Research Action Design, September 2015), p 30. Accessed on September 15, 2015 from: http://ellabakercenter.org/sites/default/files/downloads/who-pays.pdf. ↩

The Prison Policy Initiative has extensively researched correctional video visitation in the U.S., finding that, ironically, while video visitation would be most useful in state prisons given the remote locations of such facilities, the technology is far more prevalent in local jails. Unfortunately, local sheriffs and private companies have been replacing in-person visits with video visits rather than giving families another option to stay in contact. See: Bernadette Rabuy and Peter Wagner, Screening Out Family Time: The for-profit video visitation industry in prisons and jails (Easthampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, January 2015). Accessed on September 3, 2015 from: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/visitation/. ↩

Les Zaitz, “New technology helps Oregon inmates stay connected,” The Oregonian, September 12, 2012. Accessed on September 3, 2015 from: http://www.oregonlive.com/pacific-northwest-news/index.ssf/2012/09/new_technology_helps_oregon_in.html. ↩

Holly Kirby, Locked up and Shipped Away: Interstate Prison Transfers & the Private Prison Industry (Austin, TX: Grassroots Leadership, November 18, 2013). Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: http://grassrootsleadership.org/locked-up-and-shipped-away. See also: Daniel Rivero, “These states’ prisons are so full that they have to ship inmates thousands of miles away,” Fusion, June 8, 2015. Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: http://fusion.net/story/146671/these-states-prisons-are-so-full-they-have-to-ship-inmates-thousands-of-miles-away/. ↩

More information is available here: http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=dcdetail&iid=275. ↩

Lauren E. Glaze and Laura M. Maruschak, Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children, (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics, August 2008), p 6. Accessed on October 14, 2015 from: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pptmc.pdf. ↩

Proposed Collection, 80 FR 9749 (Feb 24, 2015). ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.