The myth of the “revolving door:” Challenging misconceptions about recidivism

by Sarah Staudt

Last update: February 05, 2025

- Sections

- Understanding recidivism statistics

- Addressing common counter-arguments

- Moving beyond the current recidivism conversation

- Conclusion

Stories about people who commit new violent crimes following their release from jail or prison are often weaponized to push back on important criminal legal system reforms. Sometimes, opponents come armed with statistics suggesting that the majority of people who are released from prison commit new crimes. These recidivism stories and statistics often hold great weight with legislators and other decisionmakers who see it as their duty to protect the public from “dangerous people,” and they can sometimes shut down productive conversations about how to end mass incarceration.

This guide can help advocates contend with efforts to derail reforms that are based on recidivism stories and statistics. First, the guide will examine why politicians have historically over-focused on individual stories of recidivism and how advocates can combat that tendency. Second, it will look at how to understand recidivism statistics, what they mean, and why they may overstate how common recidivism actually is. Third, it will address some common misconceptions about recidivism and help advocates counter arguments against release. Lastly, it will look at other ways advocates can reframe the conversation around post-release outcomes and successes to paint a more complete and accurate picture of what ending mass incarceration looks like.

Countering the “Wille Horton Effect” requires challenging fearmongering head-on

Individual crime stories involving people released from prison or jail often hold immense persuasive power with decisionmakers, who fall into the logical trap of believing that a single incident is representative of a larger group. But even beyond the general human inclination to over-emphasize individual negative stories over numerous positive ones, there is specific U.S. political history that makes politicians more sensitive to these single, serious recidivism events. Perhaps the most commonly cited explanation for why recidivism looms so large in debates about reform is the so-called “Willie Horton effect.” Advocates can combat the Willie Horton effect by knowing where it comes from, understanding why it is flawed, and giving politicians tools to respond effectively and withstand the political heat that comes with it.

The Willie Horton effect refers to an infamous political ad from the 1988 presidential election that was widely credited as contributing to Michael Dukakis’s loss. A political action committee tied to the George H.W. Bush presidential campaign ran a television ad about Willie Horton, a man who committed a home invasion while released on a prison furlough program1 in Massachusetts while Michael Dukakis was governor. Despite the fact that all 50 states and the federal government had successful furlough programs in the late 1980s, the ad painted such programs as liberal policies that endangered the public, and suggested that Dukakis was personally responsible for Willie Horton’s crime.

This ad and other political strategies like it rely on two flawed ideas. The first is that one terrible act committed by a person released from custody is evidence that the entire release mechanism is flawed in all cases. The second is that political actors (be they judges, legislators, parole board members, or even governors and presidents) can be held personally responsible for the behavior of the people released by policies they enact, decisions they make, or simply the policies that were in place when they were in charge.

Advocates should know that contemporary politicians may overstate the impact of the Willie Horton effect, assuming that a single negative story will devastate their political careers. In fact, scholars of U.S. politics have pointed out that the actual effect of the Willie Horton ad was likely not as intense as the myth-making about it would have people believe. As Fordham Law Professor John Pfaff has noted, “If anything, the real ‘Willie Horton effect’ is that politicians fear a negative political hit, not that such a negative political hit will actually happen.”

Ultimately, overcoming the fear produced by the Willie Horton effect requires political courage on the part of politicians, but advocates can help foster that courage in a few key ways:

- Counter-narratives: Advocates can share compelling stories about people who were released and went on to contribute to their communities and improve society, or who have accomplished great things while still behind bars. Advocates can tell these stories in video, in writing, or better yet, facilitate incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people telling their stories directly to legislators.

- Better data and analysis: Advocates can curate accurate statistical data and analyses about how rare these events actually are. This guide will discuss how to do that in the next sections.

- Demonstrating public support: Advocates can either find or produce polling and public opinion surveys that show broad-based support for criminal legal system reform. A number of organizations, including Pew Charitable Trusts, Fwd.us, and the Alliance for Safety and Justice (which focuses specifically on the opinions of crime victims) provide national-level public opinion data. Advocates can also work to create their own surveys and polling on local issues.

- Defending reformers: Advocates can develop a reputation and track record for vocally defending politicians who voted for reform in politically difficult situations. By having a plan in place for what to do and how to rapidly respond when an ad or news article uses Willie Horton-style logic, advocates can work to control the conversation in those key, high-stress moments. They can work proactively with journalists and commentators, who are willing to go deeper than a single story, to expose the flawed premises of the Willie Horton effect and remind the public and politicians of the importance of looking at the whole picture.

Understanding and contextualizing recidivism statistics

Beyond individual stories, reformers are often faced with misleading recidivism statistics that nonetheless resonate with the public. These data points usually come in the form of flat percentages of the number of people who are re-arrested, re-convicted, or return to prison within a given time period. Drilling deeper into those statistics, however, reveals that they represent a reality that is much more complex than many politicians initially assume.

Different measures of recidivism and what they mean

When institutions talk about recidivism, they usually mean one of three definitions of “returning to criminal activity:” re-arrest, re-conviction, or return to prison. Different states track different measures, with the most common measure being re-incarceration. Each measure is either over or under inclusive, conflating a diverse range of conduct and glossing over important nuances in the data. Understanding what each measure actually means can help policymakers place them in their proper context.

Re-arrest rates cover the largest range of behavior, but usually include technical violations — violations of release conditions that are not new crimes, like missing appointments or testing positive for drugs. Re-arrest rates also include people who were arrested but never convicted of a crime. Patterns of arrest vary by neighborhood, and Black and Brown communities are policed more heavily than others, leading to more arrests for minor offenses. In other words, re-arrest rates may be as much a function of where someone lives as what they did.

Re-conviction rates do not include technical violations, but may include convictions for relatively minor offenses. This measure may also underestimate how many people are actually returning to prison, since it ignores those who are returning on technical violations.

Re-incarceration rates are the most commonly recorded measure. They usually include technical violations which, depending on the state, may be a large or small portion of the people returning to prison.

Advocates should be sure to understand what recidivism measure their state is using and help politicians understand the differences between these numbers.

How high is recidivism, really?

When many people hear a recidivism rate, they think it is an answer to the question, “how likely is it that an individual person who is released (such as a person up for parole) returns to prison?” But that’s not actually what most recidivism numbers describe. The likelihood an individual person will commit a new crime is contingent on a wide range of factors, and recidivism numbers provide a misleading and oversimplified answer to that question.

Coming up with a national recidivism rate is a tricky proposition. States differ widely in how they calculate recidivism rates, and even among states that calculate them the same way, three-year re-incarceration rates range from 19% in South Carolina to 59% in Alaska. The most recent nationwide statistics seem to suggest that some form of recidivism is the experience of the majority of people released from prison, but there are good reasons to be cautious with this interpretation. The Bureau of Justice Statistics examined a cohort of people released in 24 states in 2008, and found that 66% of them were re-arrested within three years, 48% had an arrest that led to a conviction, and 49% returned to prison. However, correctional institutions and re-entry services have made efforts in states across the country to reduce recidivism in recent decades, and the Council on State Governments estimates that national three-year return-to-prison rates have fallen by 23% since 2008.

In addition, almost all recidivism statistics are calculated based on a “cohort model,” which looks at all the people released in a given time period (usually a year) and then follows them for one or more years to determine how many of them were re-arrested, re-convicted, or returned to prison. Because cohorts look at a slice of the prison population that was released in a given year, they overrepresent people who have cycled through prisons multiple times.2 These people have higher rates of recidivism. One study has noted that when these cohort recidivism rates are properly weighted, the overall recidivism rate drops from about 50% to about 33%, and only about 11% of people return to prison multiple times.3

Technical violations distort our understanding of recidivism

People often interpret recidivism rates as proof that people who go to prison are somehow irredeemable, or are largely “career criminals” who commit violent crimes repeatedly. But recidivism is only partially a measure of individual choices to continue criminal behavior. It is also a measure of how community supervision systems set and enforce rules.

Including technical violations in recidivism numbers helps present an accurate picture of how many people are cycling in and out of prisons, but it muddies the waters in terms of using recidivism as a measure of harm. Many people implicitly assume that recidivism rates refer to the number of people who committed new crimes that harmed society. However, the Council of State Governments estimated that in 2021, 29% of prison admissions nationwide were for technical violations of probation or parole.4 In other words, a recidivism statistic may tell us more about how strict a state’s probation and parole systems are than how likely someone is to commit a new crime.

When advocates are faced with a recidivism statistic, they should ask questions about what kinds of behavior the number includes and provide examples to politicians to help them understand and contextualize the raw percentages. For example, if they discover that the re-incarceration rate produced by the department includes technical violations, they should examine what percentage of re-incarcerations in their state are for technical violations, to help politicians understand how common committing a new crime really is.

Unpacking the differences between violent and non-violent recidivism

Too often, all or most recidivism is assumed to be serious violent crime. But even after technical violations are taken out of the equation, recidivism still lumps together a wide range of criminal behavior, including much less serious offenses. Few states keep data that break out what offenses people are arrested, convicted, or reincarcerated for after release, but those that do show a very small number of violent events. In California, only 7% of people were convicted in the broad category of “felony crimes against persons” within three years of release. The majority of released people (58%) had no convictions at all; of those who had convictions, about half were for misdemeanors. Meanwhile, New York — which records the crime for which people return to prison within three years — found less than 2% of people returned to prison for murder, and about 2% returned for sex-related offenses.

Arrests can be more dependent on where someone lives and their poverty level than their likelihood of engaging in criminal activity. For example, although white and Black people use and sell drugs at similar rates, Black people are more likely than white people to be arrested for drug law violations. Black drivers are more likely to be stopped by police in traffic stops, and Black and Latinx people are more likely to have their cars searched during traffic stops.

Advocates should carefully examine recidivism statistics and see if departments have more detailed data about what kinds of arrests, convictions, or re-incarcerations they encompass. It is always important to keep racial disparities in policing in mind when looking at recidivism rates, particularly for drug and public order offenses. Lastly, advocates should remember that categories like “violent” and “non-violent” do not always mean what they seem to; in some states, everything from purse-snatching to stealing drugs can be considered “violent crimes.”

Addressing common counter-arguments: people incarcerated for violent or sex-related crimes

Arguments about recidivism often center around charge-based carveouts — the idea that reforms should not be available for certain categories of incarcerated people because of their crime of conviction. Often, these carveouts are justified with arguments about recidivism and claims that people who have been incarcerated for violent or sex-related offenses are more dangerous to release than people with other kinds of charges. The evidence, however, shows the opposite.

People incarcerated for violent offenses have some of the lowest recidivism rates

Decisionmakers are often reluctant to extend reforms to people incarcerated for violent offenses, particularly when it comes to parole and other forms of early release. This reluctance means that these reforms often cannot successfully make a dent in mass incarceration since 63% of people in state prisons are locked up for a violent offense — including 15% who are locked up for murder and 16% who are locked up for rape or sexual assault. Recidivism statistics, however, show that this group of people is among the least likely to be re-arrested for any crime, convicted of any crime, or incarcerated for any crime. Only about 25% of people released from prison for a violent offense are re-arrested for another violent offense within three years. This is a much lower rate than the rates at which people with drug, property, and public order offenses are arrested for crimes similar to their crime of conviction.

Age is one likely reason why people convicted of violent offenses tend to have lower recidivism rates. Because people with violent charges generally serve longer sentences, they are generally older when released, and age is one of the main predictors of both recidivism and violence. There have now been multiple examples around the country of large-scale releases of people charged with serious violent crimes, and the recidivism rates of these groups have been extraordinarily low.

- In 2012, a ruling by the Maryland Supreme Court in a case known as Unger vs. Maryland created a kind of natural experiment: 188 people — 80% of whom were charged with murder and 16% of whom were charged with rape — were freed because of faulty jury instructions in their cases. This group of released people, commonly referred to as “the Ungers,” was tracked and returned to prison at a rate of less than 3%. It is worth noting that the Ungers received robust reentry services to help them reintegrate into the community after long prison sentences.

- A 2011 Stanford Law School study of 860 people with life sentences released from California prisons between 1995 and 2010 found that only 5 people returned to jail or prison after release, and none for a new life-sentence crime.

These case studies suggest that the people decisionmakers are often the least willing to grant relief to — people with serious violent charges and extremely long sentences — actually pose almost no risk of future violence.

People incarcerated for sex-related offenses are highly unlikely to recidivate

One of the most enduring myths about recidivism is that people charged with sex-related offenses are more likely to recidivate than other people, or are more likely to commit the same kind of crime again. Alarmist framing around this issue is common, even from research organizations that should know better, like the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

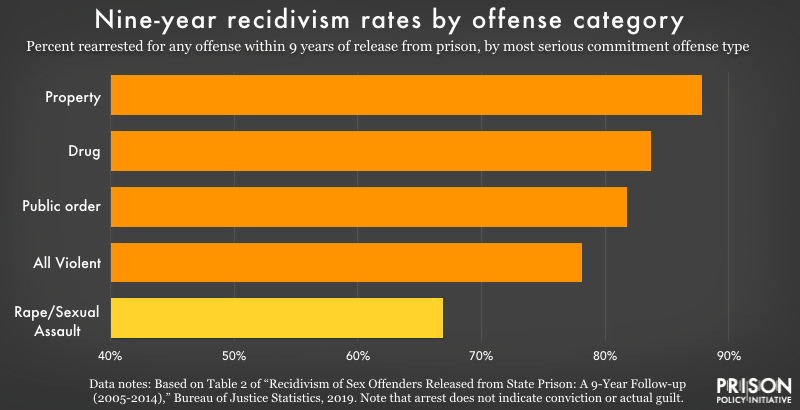

It is true that, overall, people who re-offend are likely to commit the same crime they were incarcerated for: people charged with property crimes are more likely to be later charged for another property crime, for example. The same is true for sex-related and violence-related charges. However, people with rape and sexual assault convictions have the lowest overall nine-year re-arrest rate of any offense group.

Despite these statistics, the persistent belief that people with sex-related charges are more likely to recidivate has fueled unique harms for those people, including civil commitment schemes that keep people confined long after their sentences are finished, as well as a host of draconian regulations that make reentry particularly difficult for people who must register on a sex offender registry.

Decisionmakers will often respond to these statistics about people with sex-related and violent convictions by arguing that “even a little risk is too much.” Advocates will sometimes hear arguments along the lines of “if keeping more people in prison prevents just one new crime, it’s worth it.” This argument has emotional resonance; crime can do immense harm to victims that lasts decades or lifetimes, and trying to prevent this harm is an understandable impulse. However, given the low rates of violent recidivism, the reality is that most crime is not going to be prevented by keeping people in prison longer. What is being prevented is the value that person can add to society, their families, and communities. In addition, the immense amount of money spent on prisons diverts resources from crime prevention strategies that actually work.

Moving beyond the current recidivism conversation

Often, higher recidivism rates among a particular group of people are seen only as a reason to incarcerate them more often and for longer periods of time. But advocates can see higher recidivism rates as a failure of the status quo, and call for more intentional services and other efforts to mitigate the factors that lead to recidivism. For example, helping secure employment for younger released people, rather than erecting barriers to their success, would almost certainly reduce recidivism much more effectively than keeping people in prison longer.

Recidivism should not be seen as the be-all, end-all measure of post-release success. Many people who are not arrested after release are also not thriving in their communities, and a single arrest or re-incarceration does not automatically signal that a person has failed to re-integrate into their community successfully. This is especially true considering those recidivism events often reflect the severity of probation and parole conditions rather than criminal behavior. Instead, advocates can push politicians to pay attention to alternative measures of post-release success that both signal the gradual process of desisting from criminal behavior and encourage conversations about where else investments can be made to keep people out of jails and prisons. Too often, information about these alternative measures is not collected at all, either by government agencies or researchers. These measures might include employment,5 housing,6 education,7 substance use, social relationships and family ties, and successful completion of community supervision.

Advocates should also push for legislatures and agencies to remove impediments to success by shortening probation and parole terms, reducing technical requirements, and banning incarceration for technical violations. Holding the threat of incarceration over people’s heads for non-criminal conduct increases incarceration without increasing safety. Most importantly, advocates should encourage decision-makers to invest in the communities to which large numbers of people return from incarceration, so that those neighborhoods are hubs for jobs, good housing, and educational opportunities.

Conclusion

Recidivism stories and statistics must always be placed in context to be properly understood. Inappropriate use of these stories and statistics has been used as a cudgel to beat back important, widely popular reforms that could help dismantle mass incarceration. As advocates continue to push for change, they should work to educate decisionmakers on the complexities of recidivism, and give them better tools to understand the experiences of people released from prisons and jails.

Footnotes

Prison furlough programs allowed people serving time in prison to return home for brief weekend stays to facilitate later reentry. ↩

In an article on the blog of the London School of Economics website, scholar William Rhodes used this helpful analogy to explain the problem with weighting and cohorts: “When performing mall intercept surveys, researchers randomly sample shoppers who appear in the mall during the period when the survey is administered and ask respondents questions such as: How frequently do you visit a mall? Obviously, frequent mall visitors are overrepresented in intercept surveys, so when they analyze survey data, statisticians weight the data to correctly represent all mall visitors. Offenders who repeatedly return to prison are like frequent mall visitors — they are overrepresented in samples used to estimate the rate at which offenders return to prison. If a statistician fails to weight his statistics to correct for this overrepresentation, offenders will appear to be highly recidivistic.” ↩

For an example of this kind of adjustment of recidivism rates, see Pennsylvania’s 2022 recidivism report, which found that its adjusted recidivism rate was 10 percentage points lower than its unadjusted rate. ↩

It is true that technical violations sometimes involve a new arrest and thus represent some measure of criminal behavior. However, even these arrest-related technical violations do not necessarily represent new crimes. Because the standard of proof is lower for technical violations than it is to prove someone guilty of a crime, people reincarcerated for technical violations after arrests may never have been convicted of the crime had the case gone through normal, non-community supervision processes. ↩

Employment measures might include whether people are employed, whether they are employed full or part time, and whether they are earning a living wage. ↩

Housing measures can include housing stability measures, like the number of times people move within a given time period. ↩

Education measures can include both whether someone has attained certificates and degrees as well as whether they are enrolled in education programs. ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.