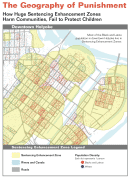

The Geography of Punishment:

How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children

by Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner, and William Goldberg

Prison Policy Initiative

July 2008

Section:

Executive Summary

Since 1989, Massachusetts has required that certain drug offenses receive a mandatory minimum sentence of two years’ incarceration if the offense occurs within 1,000 feet of a school. The law has been amended twice, first to add 100-foot zones around parks and playgrounds and then to create 1,000-foot zones around accredited daycare centers and Head Start facilities. Originally intended to protect children from the adverse effects of drugs and drug-related activity, the law was part of a legislative package put forth by Governor Dukakis to “get drugs out of our schools by 1990.”[1] The sentencing enhancement zones were intended to work as a geographic deterrent; identifying specific areas where children gather and driving drug offenders away from them with the threat of the enhanced penalty. However, the law does not require that the defendant be aware of the zone, and applies regardless of proximity to the protected location, whether school is in session, and whether children are present. Although unseen at the time, these fundamental flaws guaranteed that the law would not work.

A decade of empirical research has shown that the law fails to move drug activity away from children while subjecting Black and Latino defendants to longer sentences. Previous research by William Brownsberger and Susan Aromaa indicates that the statute’s passage has failed to move drug dealers away from schools. The Justice Policy Institute’s report Disparity by Design has demonstrated that extensive sentencing enhancement zones result in harsher sentences for Black and Latino defendants because they tend to live in urban areas, where zones often blanket large areas. The Massachusetts Sentencing Commission, has noted that “more drug dealer arrests and standard-length incarceration” are more effective than mandatory minimums at reducing drug consumption and drug-related crime, and that “treatment of drug offenders is the most effective approach of all.”[2]

This report is the first to study the geography of Massachusetts’ zone law in both urban and rural areas and to determine whether a racial disparity exists between the populations inside and outside the zones. Mapping rural and urban zones’ demographic makeup and analyzing sentencing data in Massachusetts’ Hampden County, the authors found significant punitive inequalities inherent in the law’s structure, even though rural and urban children use drugs at the same rates. We determined that this directly translates to greater rates of incarceration for Black, Latino, urban, and poor defendants, without improving children’s safety. The findings include:

- Residents of urban areas are five times more likely to live in a zone than those in rural areas.

- Latinos are almost twice as likely as Whites to live in a zone and be subject to the enhanced penalty.

- Since the boundaries of the zones are nearly impossible to reliably estimate and avoid, the statute fails to move drug activity away from schools, parks and other locations where children are present.

- People are difficult or impossible to see from 1,000 feet away, especially in urban areas, where even whole school buildings can disappear from view. The legislature should not have assumed that all drug offenders within 1,000 feet of a school are intending to sell to people at the school.

The report offers three suggestions to improve the law’s ability to protect children from the drug trade and reduce its disproportionate effect on urban, Black, Latino, and poor populations.

- Restore judges’ discretion in sentencing, so that harsh sentences intended for adults who deal drugs to children are not automatically imposed on all defendants who live near schools.

- Repeal the mandatory minimum sentence for drug offenses near schools and instead enforce existing laws that create sentencing enhancements for selling drugs to children or using children in drug transactions.

- Reduce the sentencing enhancement zones to 100 feet around schools to match the distance around parks and require that the property line of designated areas be marked. This would create a more logical protected area and would more effectively shift drug activity away from schools and parks. Smaller zones would also drastically reduce the current law’s disparity in sentencing.

By continuing to enforce the sentencing enhancement zone law, the Commonwealth is spending huge sums to incarcerate minor drug offenders who were not endangering children. Fruitless incarceration of these addicts costs the state more than $31 million a year, when it would cost much less to provide effective drug treatment. As the state’s budget deficit is predicted to surpass $3 billion, it is both ethically and fiscally necessary to reform legislation that incarcerates large numbers of people, for long periods, for minor offenses. This is especially true when that legislation not only fails its objective to protect children, but also has a detrimental effect in disproportionately affecting minority communities.

Endnotes

[1] Peter B. Sleeper, Bill would try to curb schoolyard drug sales, THE BOSTON GLOBE January 7, 1989 at 30.

[2] MASSACHUSETTS SENTENCING COMMISSION, SENTENCING GUIDELINES LEGISLATION, Questions and Answers Section 5, (2003).

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.