The Geography of Punishment:

How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children

by Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner, and William Goldberg

Prison Policy Initiative

July 2008

Section:

Recommendations

A law aimed at reducing children’s exposure to drugs should punish those specific crimes, not generalize about the nature of the activity within a huge area. Though the sentencing enhancement zone statute was written for an important purpose, its fundamental flaws ensure its complete ineffectiveness as a deterrent. In addition, it does insidious and devastating harm to urban, minority, and poor populations.

As Vermont’s example has shown, however, the legislation may be rewritten to improve public safety and eliminate the present inherent injustices. (See sidebar: Vermont’s unique sentencing enhancement zone statute emphasizes that the zone laws should be highly specific and only one of many responses to drugs.) Reform would allow the state to spend its limited criminal justice resources on effective policies, instead of squandering them on small-time addicts who do not endanger children.

In writing this report, we set out to discover whether the sentencing enhancement zone law punished certain populations more harshly because of where they live, and whether 1,000 feet was a logical or effective distance for a geography-based sentencing enhancement. We found that, despite the legislature’s good intentions, the first supposition was true and the second was not, resulting in a statute that is both harmful and ineffective. Here we identify three possible courses of action, all of which would improve children’s safety and reduce the law’s negative effects. The law may be amended to apply only to adults dealing drugs to children, it may be repealed entirely, or it may be modified so that the zones are shrunk to more reasonable sizes.

1. Amend the law to exempt people and behaviors outside the law’s purpose of protecting children from drug-dealing adults.

Simple changes could eliminate many of the current law’s inefficiencies and injustices:

- Exempt incidents where children are not present.

- Exempt children from being charged as enhancement zone violators themselves.

- Exempt incidents where two people are privately sharing drugs and money does not change hands.

- Apply zone charges only to distribution, not the ambiguous “possession with intent,” so that drug addicts are not charged as drug dealers.

- Exclude drug sales that take place in private residences, out of view of the public.

- Give judges the discretion to determine the sentence for a school zone offense and whether such a sentence may be served concurrently. Judges are uniquely qualified to review the facts of specific cases and determine the appropriate sentences. Rather than enumerate a long list of exceptions to the mandatory minimum, the legislature should allow judges to determine a sentence that coincides with the law’s intent.

These amendments — which already exist in many states[32] — would eliminate many situations where a long zone sentence would not enhance children’s safety, yet a judge must order it. However, these amendments would not cure the serious geographic flaws identified in this report.

2. Repeal the sentencing zone statute and enforce the existing laws which are narrowly tailored to deter the specific behavior of selling drugs to or in the presence of children. Depending on the drug involved, Chapter 94C, S32F provides for mandatory minimum sentences of at least two to five years for drugs sold to a person under the age of 18. Section 32K provides for a mandatory sentence of five years for “inducing or abetting minor to distribute or sell controlled substances.”

3. Modify the sentencing zone law so that it could work.

We argued above that the 1,000-foot distance was a fundamental flaw in the statute that prevented it from working effectively. In order for the law to function as a geographic deterrent, offenders must be able to identify the borders of the zones and be able to leave them without unintentionally stepping into others. The best way to ensure this is to limit the number of places that qualify for zone protection, limit the size of the zones themselves, and mark the borders clearly.

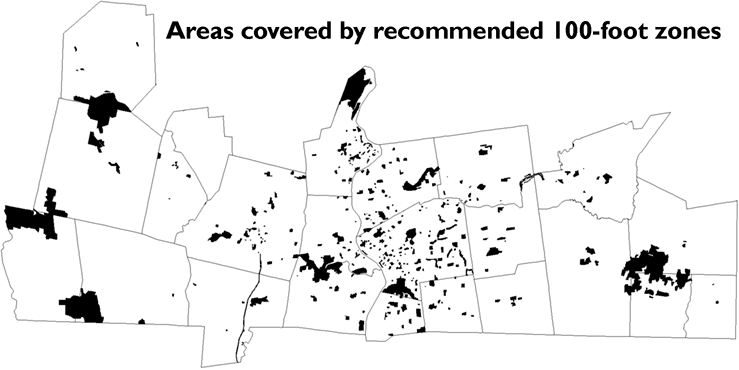

If the legislature retains the enhancement zones, we recommend reducing the zones’ size to 100 feet around schools and parks, so that they may effectively steer drug activity away from children. Unlike the current 1,000-foot distance, 100 feet is relatively easy to identify. Posting signs at the corners of the zone properties, explaining the zones and the penalty for violation, would be clear enough to work as a geographic deterrent.

Reducing the size of the school zones would also reduce the statute’s disparity in sentencing. We calculated the zones that would exist if the law specified a 100-foot distance and did not apply to Head Start facilities added in the 1998 amendments. As the map below reflects, sizable areas in Hampden County would still be eligible for the zone enhancement, but our research suggests that the racial disparity in sentencing would drop. Under such a statute, 6% of the county would be living in a zone. That population would be 6% White, 8% Black, and 9% Latino, a significantly smaller disparity. (See Table 3.)

Figure 7. Shrinking the zones to 100 feet will make them more effective at moving drug dealing away from children and less harmful to Black and Latino communities.

| Current statute | Recommended statute | |

|---|---|---|

| Percent of county living in sentencing enhancement zones | 36% | 6% |

| White people living in sentencing enhancement zones | 29% | 6% |

| Black people living in sentencing enhancement zones | 52% | 8% |

| Latino people living in sentencing enhancement zones | 59% | 9% |

Footnotes

[32] E.g. 16 Del. C. S4767(a)(2)(d) (an affirmative defense where the activity was on private property, not done for profit, and no minors were present), Conn. Gen. Stat. S21a-279(d) (excludes any person enrolled in the school or daycare), N.C. Gen Stat. S90-95(e)(5), (8), (10) (applies a lower class of felony depending on the ages of the people involved, and excludes sharing small amounts of marijuana), 18 V.S.A. S4237(a), (b), (c)(3) (penalty is age-dependant, and exempts sharing drugs on adjoining property out of public view).

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.