Sam Durant's installation "Labyrinth" in Philadelphia uses our research

by Peter Wagner,

October 30, 2015

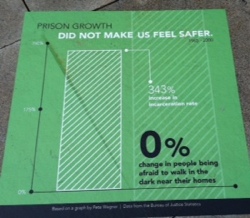

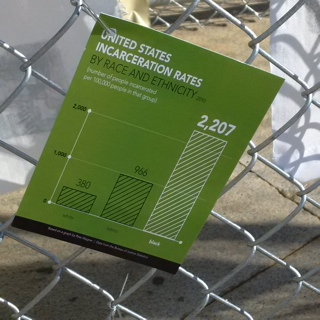

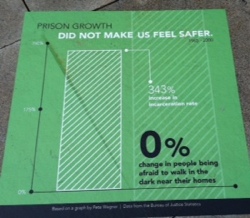

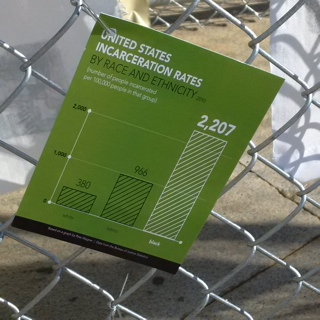

For the month of October, some of our research is hanging in a public art installation about mass incarceration just outside of Philadelphia City Hall. The central element of artist Sam Durant’s installation “Labyrinth”, designed in collaboration with men incarcerated at Graterford State prison, is a large maze made of chain-link fencing.

For the month of October, some of our research is hanging in a public art installation about mass incarceration just outside of Philadelphia City Hall. The central element of artist Sam Durant’s installation “Labyrinth”, designed in collaboration with men incarcerated at Graterford State prison, is a large maze made of chain-link fencing.

Within and around the maze are some facts about mass incarceration and the public is invited to leave their comments.

While we often collaborate with artists, that our research was used in this show was a pleasant surprise. We intend our work to be used in new and exciting ways to advance the movement against mass incarceration, and we are thrilled that Sam Durant found a way to do so.

For more on this exhibition, see these two great articles with more pictures of the entire exhibition:

And thanks to Patrick Griffin and Angus Love for sending us these photos of our work in action!

The Federal Communications Commission today approved a new order regulating the prison and jail telephone industry and reducing the cost of calling home from prisons and jails

by Peter Wagner,

October 22, 2015

The Federal Communications Commission today approved a new order regulating the prison and jail telephone industry and reducing the cost of calling home from prisons and jails.

You can read the FCC’s press release and summary of the decision and see our October 1 analysis of the FCC’s “fact sheet” that compares the proposed order to the exploitative status quo.

We’ll have a detailed analysis after the full text of the FCC’s order is publicly available, but for now we note only one possible change from our October 1 post: The FCC is proposing to give the industry an additional 3 months to bring their contracts in jails into compliance with the new rules. That means that people with loved ones in state prisons should see the impact in about February, and with those in jails in about May 2016.

Thank you Commissioner Clyburn, Chairman Wheeler, and Commissioner Rosenworcel for taking such strong action to protect the most vulnerable families in this country from this exploitative industry.

We're hiring for a Policy & Communications Associate! Please apply and spread the word.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

October 22, 2015

Are you interested in joining our dedicated team to produce cutting edge research to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization? Do you want to shape innovative advocacy campaigns and spark critical discourse to create a more just society?

Are you interested in joining our dedicated team to produce cutting edge research to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization? Do you want to shape innovative advocacy campaigns and spark critical discourse to create a more just society?

If so, our new employment opportunity Policy & Communications Associate might be for you. Please spread the word, and if you think the position is for you, please apply.

by Peter Wagner,

October 21, 2015

Yesterday, the top judge in Massachusetts cited our research in his “State of the Judiciary” address.

Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Ralph D. Gants made a strong argument for sentencing reform and used our report States of Incarceration: The Global Context to argue that Massachusetts, a state with one of the lowest rates of incarceration in the nation, should and can do so much more:

If we believe that the vast majority of the 46 percent of prisoners currently being released from state prison without any post-release supervision should have post-release supervision, how are we to pay for it? One alternative is to redirect the money that would be saved by reducing the length, and therefore the rate, of incarceration. How can we do that? After all, are we not among the states with the lowest rate of incarceration? It is true that in a nation that has gone mad with mass incarceration, we have maintained some semblance of sanity; our rate of incarceration is less than one-half of the national average. But our rate of incarceration is three times what it was when I graduated from law school in 1980, even though our rate of violent crime today is roughly 22 percent lower than in 1980 and our rate of property crime is nearly 57 percent lower. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, if Massachusetts were a separate nation, our rate of incarceration would be the eighth highest in the world, exceeded only by the United States (which ranks first), Russia, Cuba, El Salvador, Thailand, Azerbaijan, and Rwanda; it is 2 1/2 times higher than the rate in the United Kingdom. There is certainly room in Massachusetts for justice reinvestment and I am confident we can find common ground with the Legislature and the Governor on ways to be smarter on sentencing so that we can reduce both the rate of incarceration and the rate of recidivism.

We were also thrilled to see the Judge draw attention to what should be a common sense reform: criminal justice fees. Chief Justice Gants said:

And if we are truly committed to reducing recidivism, should we not take a fresh look at the various fees we impose on criminal defendants that go to the state’s general fund? Indigent counsel fee: $150. Probation supervision fee: $780 for one year of supervised probation and $600 per year for administrative probation. Victim-witness fee: $90 for a felony, $50 for a misdemeanor. For an indigent defendant convicted of one felony and sentenced to one year of supervised probation, the fees total $1,020, more if a GPS bracelet is a condition of probation, because the defendant is required to pay for that, too. A judge may waive payment where the judge finds it would cause undue hardship, but judges must then require community service in lieu of payment, and the probation department must find the defendant an appropriate community service opportunity.

I know that Massachusetts is not unique in the imposition of these fees. At least 44 states impose a probation supervision fee; at least 43 impose an indigent counsel fee. I also know that the revenue yielded by these fees in Massachusetts is not insubstantial: $21 million in probation supervision fees; $7 million in indigent counsel fees; about $2.4 million in victim-witness fees, in all more than $30 million per year. But should we not stop and ask: who are we asking to pay these fees? Most are dead broke, or nearly broke. Approximately 75 percent of criminal defendants are indigent. Collection is difficult, and we are asking probation officers to take charge of this collection, and to allege a violation of probation where a defendant fails to pay. And the law requires yet another payment of a $50 fee when a default warrant is issued because of a defendant’s failure to pay.

We want probationers to succeed on probation, and we want probation officers focused like a laser beam on the elements that will help probationers succeed: finding a job, getting an education, dealing with drug addiction and mental health problems, ending the cycle of domestic violence. Should we not ask whether the financial burden of these fees is making it more difficult for probationers to succeed? Is it increasing the rate of violation? Does it make sense to transform probation officers into debt collectors and community service coordinators, to burden our courts with the obligation to collect these debts, and to use the threat of a violation of probation as a means to induce payment? Are we, in the immortal words of MBA President Bob Harnais, “spending dollars to collect nickels,” and are we collecting those nickels from a population who can least afford to pay?

We have two ideas for state legislative strategies to further reduce the cost of calling home from prisons and jails.

by Peter Wagner and Aleks Kajstura,

October 21, 2015

On Thursday, the Federal Communications Commission is scheduled to vote on a proposal to cap the cost of all calls home from prisons and jails and to curtail or ban the abusive fees charged by the industry.

By capping the cost of calls and the fees, the FCC will have established a ceiling on what can be charged. But states and individual counties should — and many will — go even further. There are at least two types of state legislation that could be passed.

Idea 1: Simple fix that the facilities might not like but is really the best way to go.

Ban commissions and require all contracts to be negotiated on the basis of the lowest price to the consumer. New York Corrections Law § 623 is a great model, although an even better version would apply to contracts with local jails as well as state prisons.

Idea 2: Long-term market re-alignment.

Create a statutory ceiling on commission payments on a per minute basis in order to re-align incentives for facilities to effectively negotiate with the vendors for the lowest rates for consumers.

Currently, commissions are typically negotiated on a percentage basis, so facilities have an incentive to tolerate high customer costs, so changing to a fixed per-minute commission would change the incentives, to give the facilities an incentive to favor low-cost higher-volume calls home.

Let me explain.

The FCC’s order caps the maximum that can be charged at 11cents a minute in prisons and, depending on the size of the facility, 14-22 cents a minute in jails. For the sake of this illustration, let’s talk about jails in the 14 cents a minute category.

First, capping the cost at 14 cents will constitute a tremendous and long-needed rate reduction across the country. But how can a state easily ensure that rates continue to move downwards, even in facilities that will not waive their commission?

Under the status quo in the states that allow commissions, the facilities have an incentive to set the rates at the maximum and then demand that the vendors pay the maximum commission. So rates are likely to be at 14 cents forever. As the cost of providing service declines with further advances in technology, the cost might stay at 14 cents while the facilities demand 13.9999 cent commissions.

But if a state were to set a maximum commissions at, say, 3 cents a minute, it would give facilities an incentive to push the rates down in order to increase usage. With such a maximum per minute commission, the rates wouldn’t ever go below the commission level of 3 cents, but the facilities would have an incentive to push the rates down as close to that 3 cents as they can. (We don’t have a position on what the commission amount per minute should be, and we used 3 cents just to illustrate the math.)

As we’ve seen in New York and nationwide, lowering the total price to the families increases the call volumes.

This structure would also give the facilities an incentive to ensure that the vendor doesn’t charge unnecessary fees. Prior to the FCC’s October 2015 ruling, the companies charge hidden fees as a way to recoup lost profits from paying unsustainably high commissions. (The business model is called fee harvesting and shortchanges both the families and the facilities; but since the facilities are already receiving windfalls on the call rates, they often don’t object to the extra fees.)

The new FCC ruling will ban most of the fees that were previously charged by the industry and caps all fees that remain. But as fees eat into the money that families can spend on the actual calls, this proposal gives the facilities a financial incentive to insist on even lower fees as that would further increase the number of minutes used.

New report finds great distances discourage prison visits

October 20, 2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: October 20, 2015

Contact:

Bernadette Rabuy

(413) 527-0845

Easthampton, MA — Less than a third of people in state prison receive a visit from a loved one in a typical month, puts forth a new report by the Prison Policy Initiative, Separation by Bars and Miles: Visitation in state prisons. The report finds that distance from home is a strong predictor for whether an incarcerated person receives a visit.

Easthampton, MA — Less than a third of people in state prison receive a visit from a loved one in a typical month, puts forth a new report by the Prison Policy Initiative, Separation by Bars and Miles: Visitation in state prisons. The report finds that distance from home is a strong predictor for whether an incarcerated person receives a visit.

“For far too long, the national data on prison visits has been limited to incarcerated parents. We use extensive yet under-used Bureau of Justice Statistics data to shed light on the prison experience for all incarcerated people, finding that prisons are lonely places,” said co-author Bernadette Rabuy, who recently used the same BJS dataset for Prisons of Poverty: Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned.

Separation by Bars and Miles finds that most people in state prison are locked up over 100 miles from their families and that, unsurprisingly, these great distances — as well as the time and expense required to overcome them — actively discourage family visits. Given the obvious reluctance of state prison systems to move their facilities, the report offers six correctional policy recommendations that states can implement to protect and enhance family ties. Rabuy explained, “At this moment, as policymakers are starting to understand that millions of families are victims of mass incarceration, I hope this report gives policymakers more reasons to change the course of correctional history.”

The report focuses on incarcerated people in state prisons and is a collaboration between Prison Policy Initiative staff and data scientist Daniel Kopf of the organization’s Young Professionals Network.

The report is available at: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/prisonvisits.html

-30-

Are you are a writer, actor or video person who cares about justice? We need to talk.

by Peter Wagner,

October 16, 2015

Next Thursday, October 22, the Federal Communications Commission is scheduled to vote on historic regulation of the prison and jail telephone industry. Previous reforms have applied to some calls, but this reform will lower the cost of receiving calls home from prisons and jails for all families of incarcerated people in this country.

I expect that some of the companies and the greedier sheriffs might again sue the government for enacting this important reform. Most of the companies (except for one) are privately held and hard to influence; but sheriffs are elected by all of us.

The sheriffs will have elections coming up. I’d like to make a video addressed to voters faced with re-electing a sheriff who is suing the federal government for regulating the prison and jail telephone industry, setting the decade-long movement for phone justice back even further.

We’ll be looking for writers, actors, editors, camera people, graphic designers, etc. In February, some amazing comedians produced a series of videos that successfully shamed the video visitation industry into dropping its ban on in-person visits. We think we can convince the public of the harm that will come from re-electing sheriffs who want to charge the poorest families in their communities $1 a minute for simple phone calls, but we need your help.

Many of these Sheriffs are outside of the major media markets, but from our work on prison gerrymandering, we know how to get press coverage in rural parts of the country. We need your help to make the video exciting and to make sure it reaches a national audience.

If you or your team can help, please contact us directly or join our Young Professionals Network. (And, please, share this casting call with your networks.)

Private prisons are more like a parasite on the publicly-owned prison system, not the root cause of mass incarceration.

by Peter Wagner,

October 7, 2015

In a word: No.

Private prison companies have found ways to profit on America’s experiment with mass imprisonment, but they are, to build on Ruthie Gilmore’s analogy, less the seed or the fertilizer fueling mass incarceration and more like a parasite on the publicly-owned prison system.

The vast majority of people incarcerated in this country are incarcerated in publicly-owned prisons. Only a small minority is in facilities operated by private companies under contract with states or the federal government. (And things get a little complicated because some “outsourcing” of incarcerated people goes not to private companies but to other governments. For example, almost half of the state prison population in Louisiana is actually housed under contract with local parish governments.)

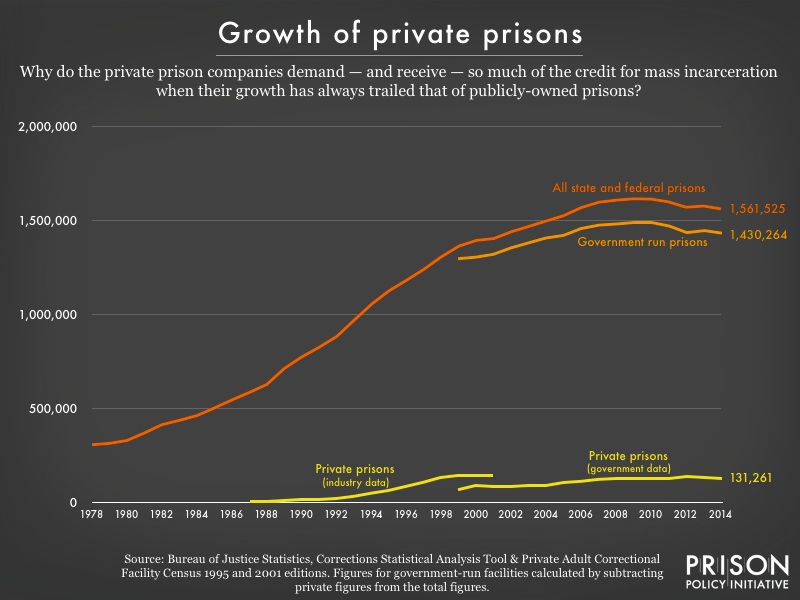

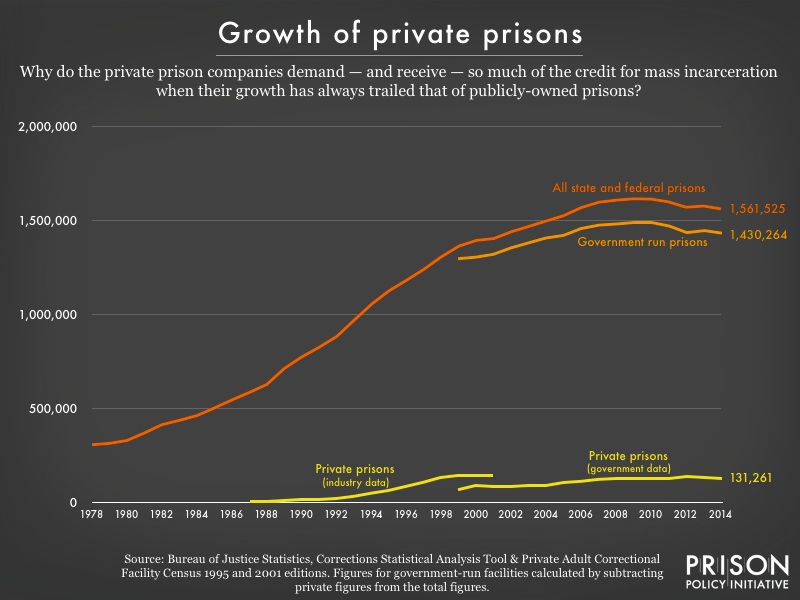

This graph illustrates the late origin and limited impact of private prisons on the national landscape of state and federal prisons:

Note that the federal government didn’t even bother to track the size of private prisons until 1999 and that we calculated the size of the government-run prisons by subtracting the private prisons from the total. The data from 1987 to 2001 was collected and published by an academic in Florida with a uniquely close relationship with the industry. Due to different methodologies, the data aren’t entirely compatible but together they show the birth and initial growth of the industry follows rather than leads the prison boom. The industry’s long plateau in the last decade makes it clear that the private prison industry has largely been locked out of sizable growth.

Note that the federal government didn’t even bother to track the size of private prisons until 1999 and that we calculated the size of the government-run prisons by subtracting the private prisons from the total. The data from 1987 to 2001 was collected and published by an academic in Florida with a uniquely close relationship with the industry. Due to different methodologies, the data aren’t entirely compatible but together they show the birth and initial growth of the industry follows rather than leads the prison boom. The industry’s long plateau in the last decade makes it clear that the private prison industry has largely been locked out of sizable growth.

Now, of course, the influence of private prisons will vary from state to state and they have in fact lobbied to keep mass incarceration going; but far more influential are political benefits that elected officials of both political parties harvested over the decades by being tough on crime as well as the billions of dollars earned by government-run prisons’ employees and private contractors and vendors.

The beneficiaries of public prison largess love it when private prisons get all of the attention. The more the public stays focused on the owners of private prisons, the less the public is questioning what would happen if the government nationalized the private prisons and ran every facility itself: Either way, we’d still have the largest prison system in the world.

But if private prisons aren’t at the root of mass incarceration, that doesn’t mean that private investors haven’t found ways to make our criminal justice system worse. The sins of the prison and jail telephone industry trying to charge families $1 a minute for simple telephone calls are well-documented. And the private bail industry keeps legislatures from passing sensible bail reforms that would allow poor, unconvicted people who pose no public safety threat to wait for their trial at home rather than in jail.

What I find most worrisome is the rush of private money to fuel the development of “alternatives” to incarceration like electronic monitoring or private probation services that ensnare people who previously would never have been under criminal justice system control. And worse, because many of these services are paid for by the person being monitored, they remove any fiscal barriers to large-scale unnecessary use.

Their proposal would give families the telephone justice they have been asking for.

by Peter Wagner,

October 1, 2015

For more than a decade, families have been calling on the Federal Communications Commission to provide relief from the exploitative prison and jail telephone industry that charges rates as high as $1/minute. We are excited to share that phone justice is now closer than ever.

Yesterday, FCC Chairman Wheeler and Commissioner Clyburn released a summary of their proposal for comprehensive regulation of the broken prison and jail telephone industry. The Federal Communications Commission will be voting on the proposal at their October 22 meeting.

The new proposal:

- Applies to all calls be they local, intra-state, or inter-state. (Previous regulations only applied to inter-state calls.)

- Lowers the maximum rate that can be charged to 11 cents a minute for state prisons, and 14 to 22 cents a minute for jails, depending on the size of the jail. (Most incarcerated people are in prisons and most people in jails are in the larger facilities that will have the lower rates.)

- Caps and bans the abusive hidden fees documented in our report Please Deposit All of Your Money: Kickbacks, Rates, and Hidden Fees in the Jail Phone Industry, that can easily double the price of a call. The proposed new fee caps are:

- Payment by phone or website: $3 (currently up to $10)

- Payment via live operator: $5.95 (currently up to $10)

- Paper bills: $2 (currently up to $3.49)

- Markups and hidden fees embedded within WesternUnion and MoneyGram payments: $0 (currently up to $6.95)

- Markups and hidden profits on mandatory taxes and regulatory fees: $0 (We’ve seen these markups and hidden profits on “mandatory” taxes be 25% of the cost of the call)

- All other ancillary fees: $0. (There are many of these charges. Some of the most egregious ones are $10 fees for refunds, $2.50/month for “network infrastructure” and a 4% charge for “validation”.)

The proposal also:

- Discourages but does not directly ban commissions (kickbacks of vendor profits to the correctional facilities).

- Bans flat-rate calling. (Currently some vendors insist on charging a fixed-price for calls of any length, so that a person who only needs a 1 minute conversation must still pay for a 15 minute call.)

- Takes effect very quickly; the new regulations will likely be effective by early 2016. (90 days after they are published in the Federal Register.)

- Seeks further comment on the video visitation industry and other advanced communications services.

Now that the FCC is finally prioritizing the families of incarcerated people, we need to keep the pressure on and make sure their final order reflects the strong protections provided in this proposal. No family should have to choose between putting food on the table and keeping in touch.

Please reach out to the FCC to urge them to pass this proposal, and ask your elected officials to do the same.

For the month of October, some of our research is hanging in a public art installation about mass incarceration just outside of Philadelphia City Hall. The central element of artist Sam Durant’s installation “Labyrinth”, designed in collaboration with men incarcerated at Graterford State prison, is a large maze made of chain-link fencing.

For the month of October, some of our research is hanging in a public art installation about mass incarceration just outside of Philadelphia City Hall. The central element of artist Sam Durant’s installation “Labyrinth”, designed in collaboration with men incarcerated at Graterford State prison, is a large maze made of chain-link fencing.

Note that the federal government didn’t even bother to track the size of private prisons until 1999 and that we calculated the size of the government-run prisons by subtracting the private prisons from the total. The data from 1987 to 2001 was collected and published by an academic in Florida with a

Note that the federal government didn’t even bother to track the size of private prisons until 1999 and that we calculated the size of the government-run prisons by subtracting the private prisons from the total. The data from 1987 to 2001 was collected and published by an academic in Florida with a