If the U.S. doesn't make reducing the correctional population a policy priority, generations will continue to be burdened by mass incarceration.

by Joshua Aiken and Wendy Sawyer,

December 30, 2016

It’s that time of the year again, when many of us like to take stock and commit to changes that will bring us closer to our goals. It’s not a bad time for policymakers to do the same.

Here at the Prison Policy Initiative, we often find it useful to look back at how our criminal justice system has evolved over time. Year-to-year fluctuations are less distracting from that perspective, so we can also identify the pivotal political changes that have had truly dramatic impacts, like the “tough on crime” policies that led to the current era of mass incarceration.

Looking forward, however, is harder when you are data-driven. It’s hard to tell how current policies will play out in the future, and the impact of policy changes is even harder to gauge. We have been warned about the dangers of extrapolating the results of past policy changes to predict the future, but this time of year encourages some imaginative thinking — so we extrapolated recent trends anyway. We hope that as new elected officials are preparing to take office, these rough projections will drive home the urgency of criminal justice reform.

To be taken with an extra-large grain of salt, here are our projections of how long it would take us to undo the aberrant buildup of correctional control in the U.S. since the 1970s, holding constant the current average yearly decline:

- It’ll be 2049 when the federal prison population returns to normal — 33 years from now.

- It’ll be 2122 when the state prison populations return to normal — 106 years from now.

- It’ll be 2084 when the local jail populations return to normal — 68 years from now.

- It’ll be 2098 when the population under probation and parole supervision returns to normal — 82 years from now.

(See how we chose the “normal” baseline in the methodology notes below.)

Policymakers can speed things up: for example, the federal prison population has declined drastically over the last five years, in large part due to policy changes. But, sadly, millions more Americans are going to be churned through jails, locked in prisons, and placed under correctional control unless lawmakers at all levels of government start taking criminal justice reform seriously. If the U.S. doesn’t make reducing the correctional population a policy priority, our children and even great-great-grandchildren are more than likely to be burdened by mass incarceration.

A few notes about methodology:

The late 1970s is an especially useful point of reference because it is right before the “war on crime” really took hold–incarceration rates had been relatively flat for decades and the number of people under correctional control had not yet exploded. In order to determine our baselines we used incarceration rates to ensure that 1975, 1977, and 1980 were representative of historical trends. We used 1975, 1977, and 1980 as our starting points, as those are the years the U.S. first started collecting yearly data on the two leading forms of correctional control: state prison populations (1975) and probation (1977). Before 1983, jail population data was recorded every ten years, so we used the count from 1980 as the closest match to the other baseline years. Federal prison population counts are available back to at least 1925; we used 1975 to match the state prison population count.

For the average yearly decline, we calculated the total decline in population from each correctional population’s peak to 2015, then divided by the number of years since the peak. To project future populations, we started with 2015’s population and subtracted the average decline for each subsequent year. This treats the annual population as an arithmetic sequence; we chose to make it as simple as possible.

These projections are for total counts, not rates, so they do not account for changes in population size. Extrapolating one set of data was dicey enough for us, without adding additional uncertainty about the size of the general population.

Sources:

The data for our projections came from the Bureau of Justice Statistics 2015 updates: see our posts on the incarcerated population and the population under probation and parole supervision.

For the federal prison population, we used 1975 as our baseline (24,131 people) and 2011 (197,050) as our peak value with an average yearly decline since the peak (4,591/year) to arrive at our projection of 2049.

For the state prison population, we used 1975 as our baseline (216,462) and 2009 (1,365,688) as our peak value with an average yearly decline since the peak (11,255/year) to arrive at our projection of 2122.

For the local jail population, we used 1980 as our baseline (163,994) and 2008 (785,533) as our peak value with an average yearly decline since the peak (8,190/year) to arrive at our projection of 2084.

For the population under probation and parole supervision, we used 1977 as our baseline (990,157) and 2007 (5,119,047) as our peak value with an average yearly decline of the probation population since the peak (62,896/year) and an average yearly increase of the parole population since the peak (18,184/year) to arrive at our projection of 2098.

2016 was another big year for powerful data visualizations from the Prison Policy Initiative. These are our 10 favorites.

by Peter Wagner and Wendy Sawyer,

December 30, 2016

2016 was another big year for powerful data visualizations from the Prison Policy Initiative. These are 10 of our favorites:

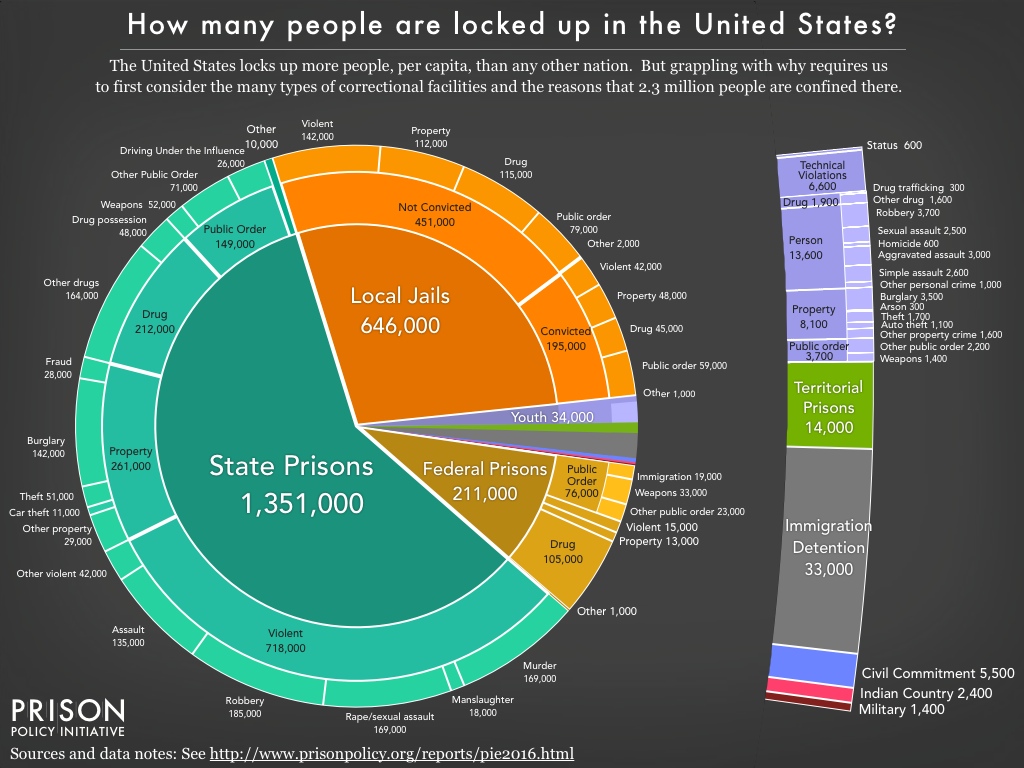

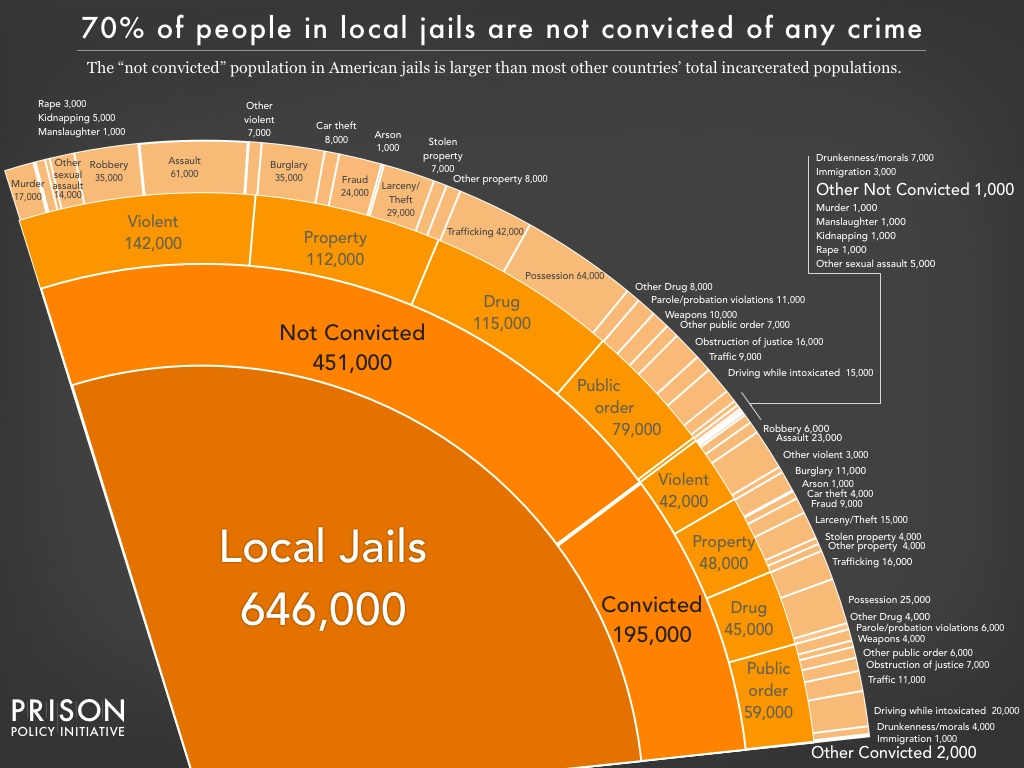

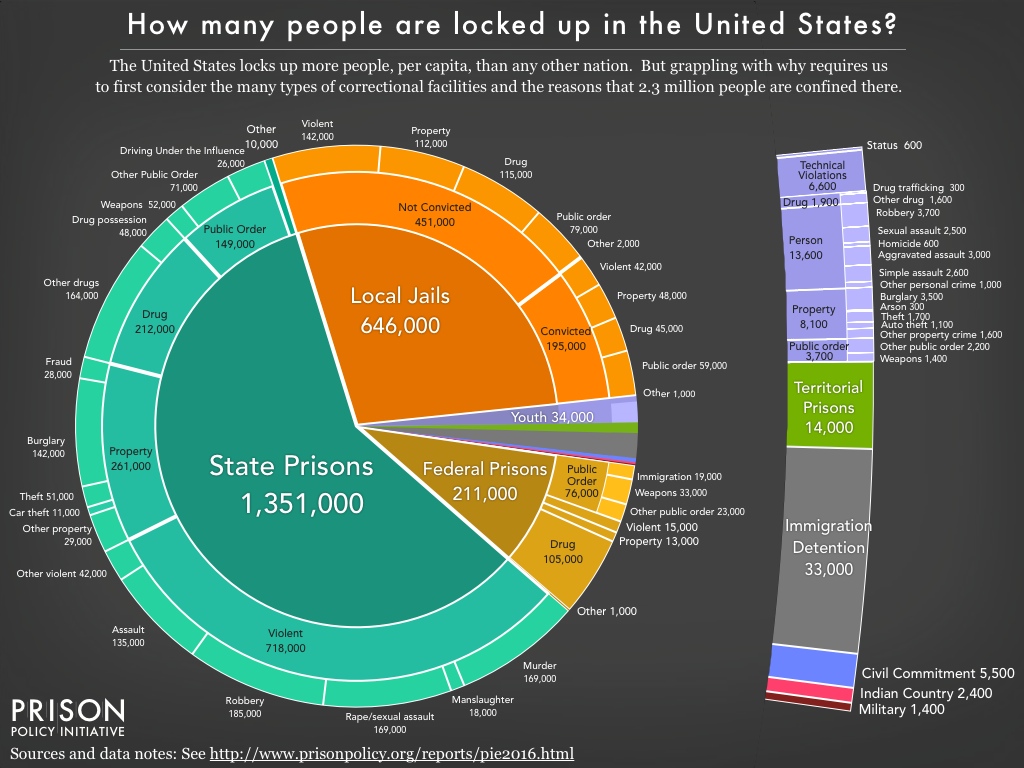

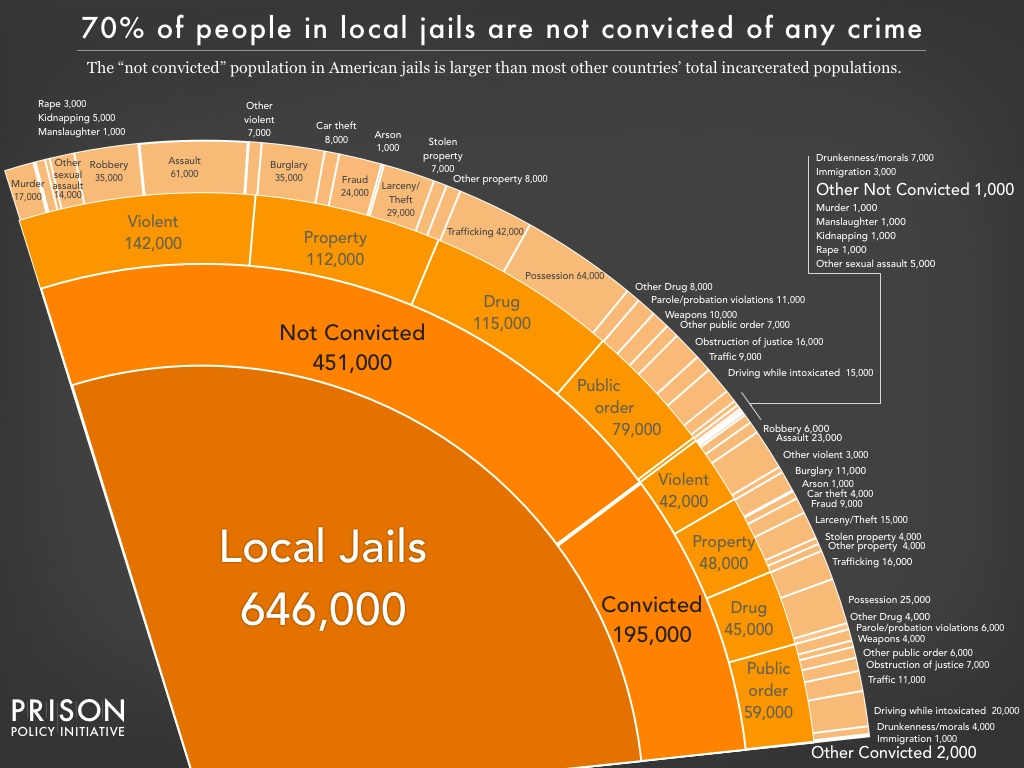

1. The “whole pie”

We updated our most famous data visualization for 2016, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie:

This year’s report included four slideshows of additional detail on different parts of the carceral system and some of the state-to-state comparisons.

Perhaps the most exciting addition was the report’s detailed dive into the population of people confined in jails, most of whom are legally innocent:

In a major update to our graph first produced last year, we powerfully illustrated that virtually all of the growth in the jail population has been in the number of legally innocent people who are detained in jails:

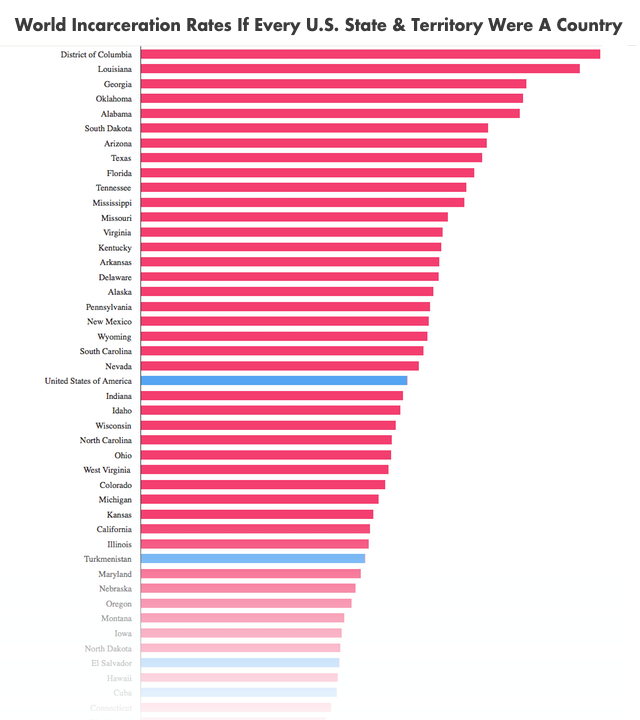

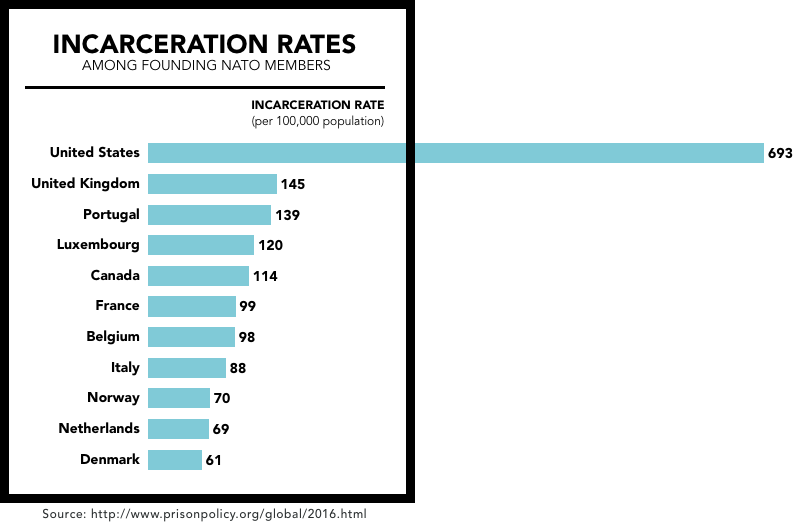

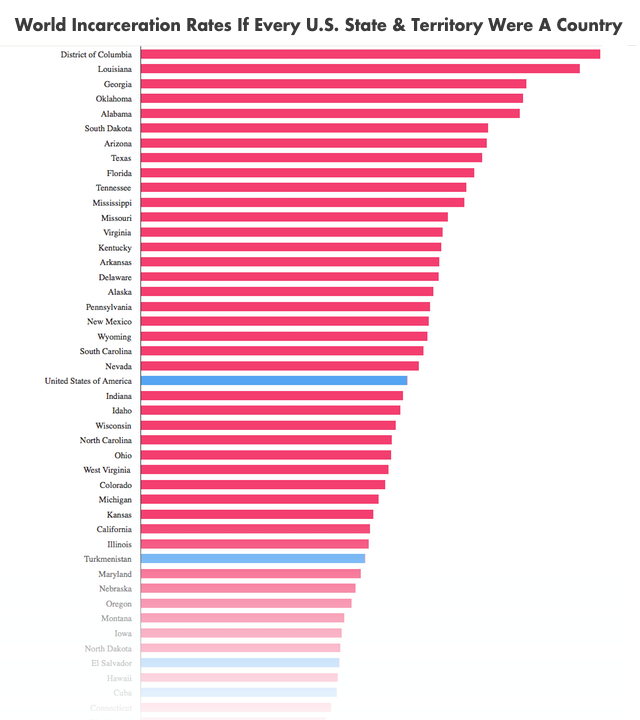

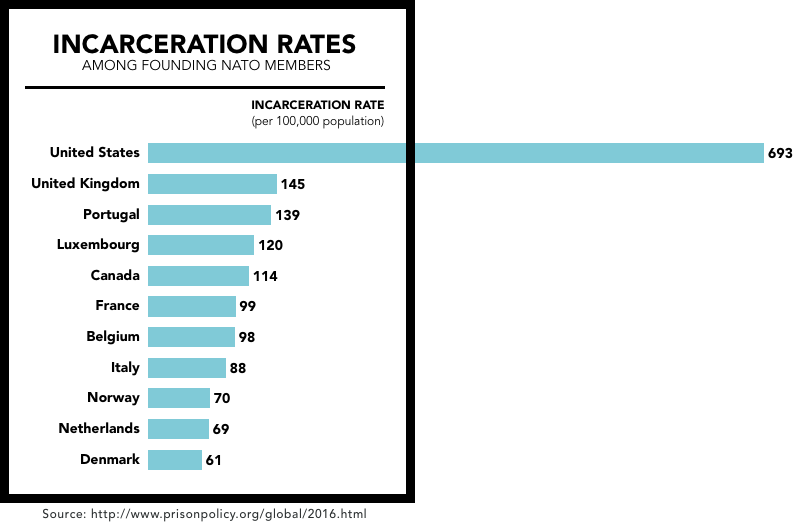

2. Every U.S. state is out step with the rest of the world

The Governors of 49 states can look at Louisiana and feel like their state is an enlightened bastion of moderation, at least on incarceration. But how do each of the 50 states compare to the countries of the world? Badly.

On the theory that comparing Iowa to El Salvador (a country that recently endured a civil war and now has one of the highest homicide rates in the world) might not be fair, the report includes a graphical comparison of the U.S. incarceration rate to that of its closest allies, the founding members of NATO:

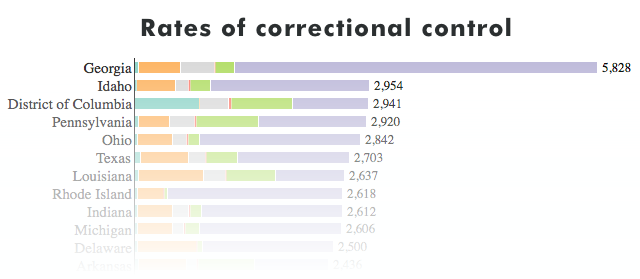

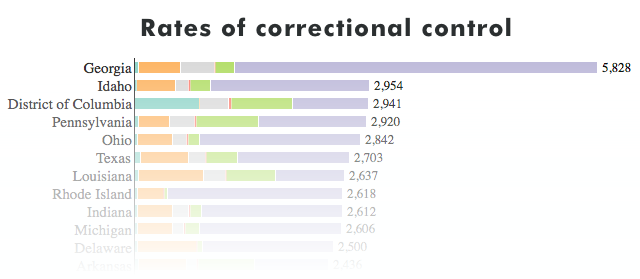

3. Looking at probation

Some of the seemingly less punitive states are actually the most likely to put their residents under some other form of correctional control, finds our report Correctional Control: Incarceration and supervision by state. The report builds off Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, to provide the big picture of mass incarceration to produce versions of the pie chart for each state.

The centerpiece of the report is an interactive chart that ranks each state and D.C. by rate of total correctional control, which includes incarceration, probation, and parole.

The report also includes an animation that illustrates just how dramatic the differences are between the states:

Thinking of the U.S. criminal justice system as one system can be a mistake. There are 50 state systems, plus one in each of the approximately 3,000 counties and often separate systems in the approximately 30,000 municipalities. These differences matter a great deal.

Thinking of the U.S. criminal justice system as one system can be a mistake. There are 50 state systems, plus one in each of the approximately 3,000 counties and often separate systems in the approximately 30,000 municipalities. These differences matter a great deal.

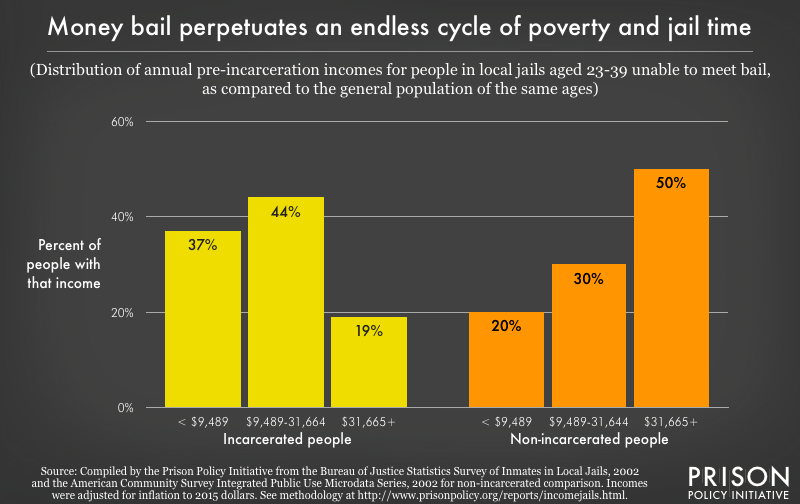

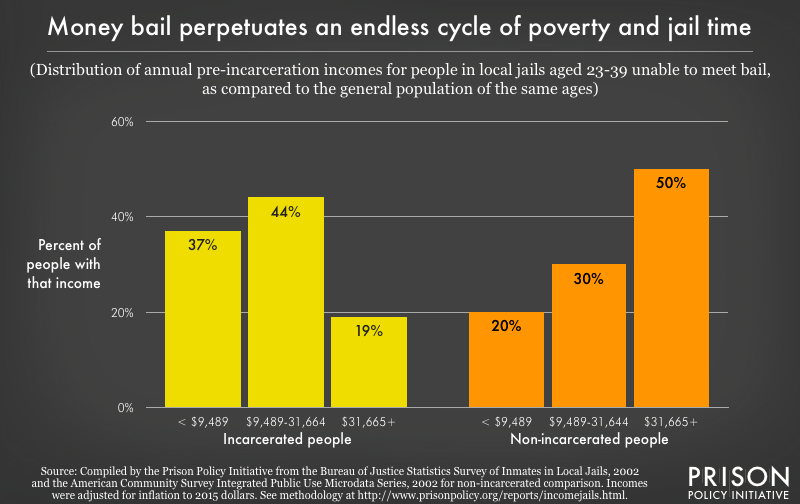

4. Bail perpetuates poverty

In May, Bernadette and Dan unlocked rare government data to show that the ability to pay money bail is impossible for too many defendants because it represents eight months of a typical defendant’s income. Detaining the Poor also showed how much harder it is for women and people of color to afford bail.

People in local jails unable to meet bail are concentrated at the lowest ends of the national income distribution, especially in comparison to non-incarcerated people. As this graph shows, 37% had no chance of being able to afford the typical amount of money bail ($10,000) since their annual income is less than the median bail amount.

People in local jails unable to meet bail are concentrated at the lowest ends of the national income distribution, especially in comparison to non-incarcerated people. As this graph shows, 37% had no chance of being able to afford the typical amount of money bail ($10,000) since their annual income is less than the median bail amount.

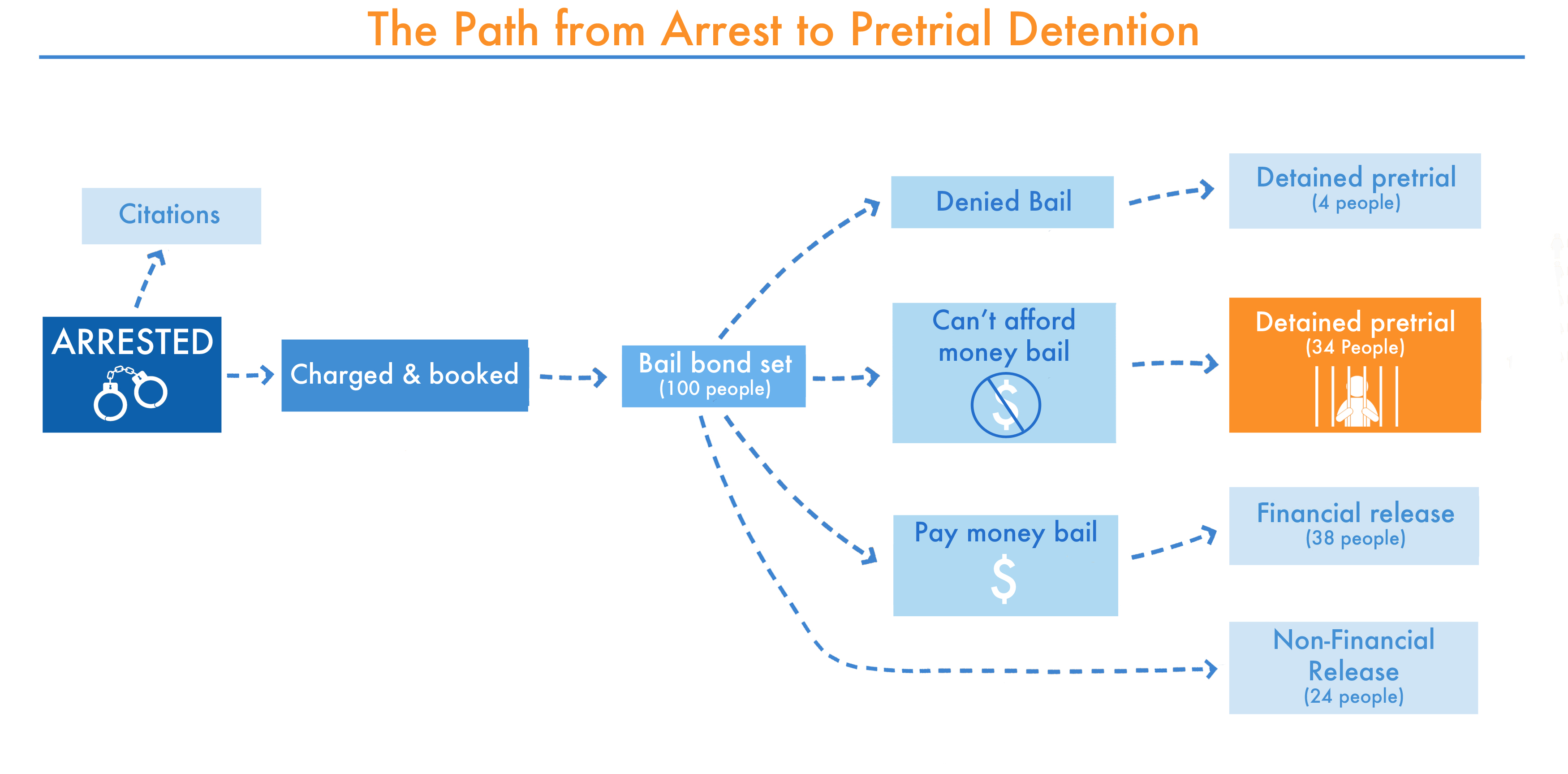

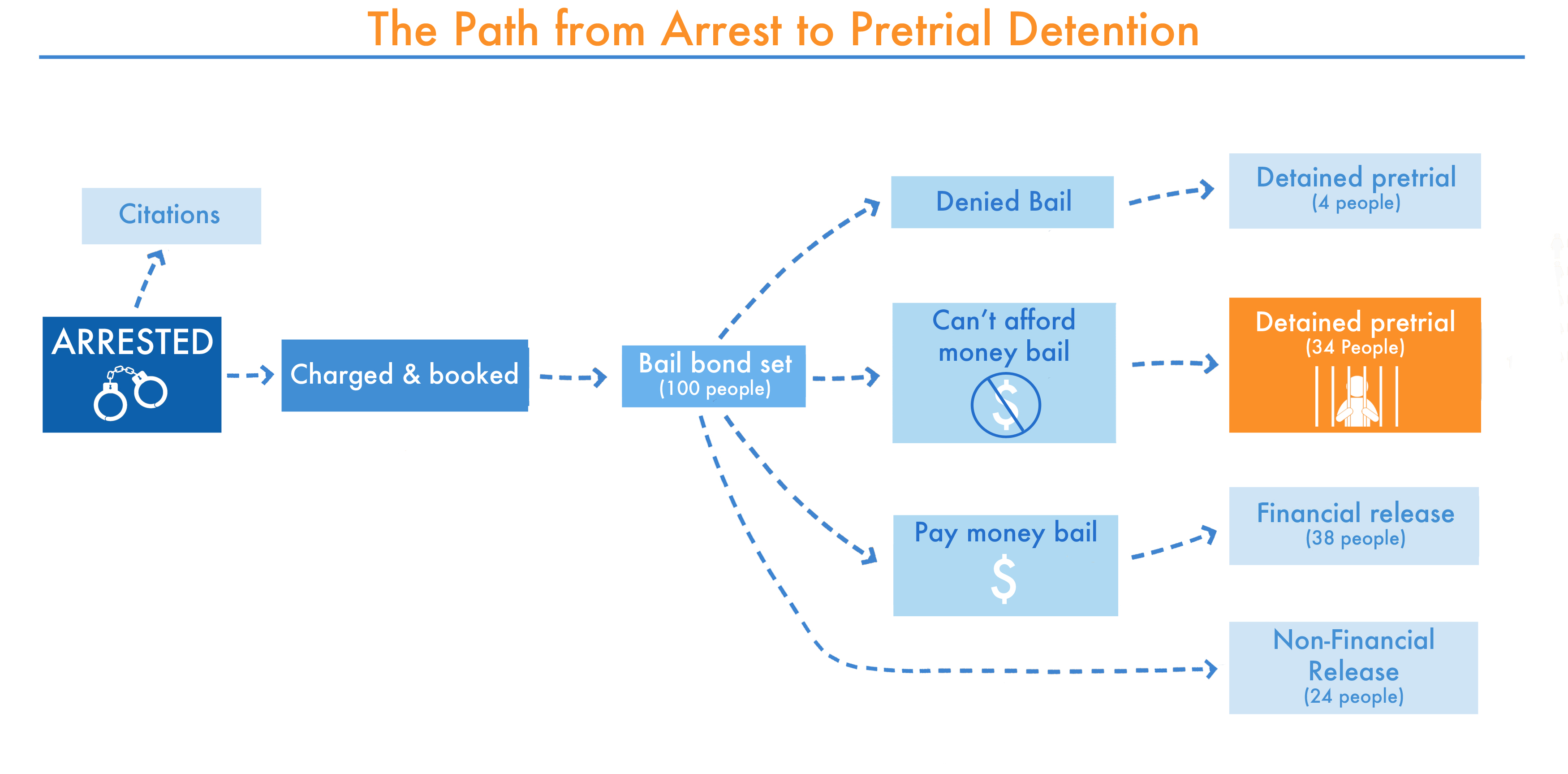

The report also includes a very helpful illustration of the path from arrest to pretrial detention:

Since the 1980s, there has been a significant, nationwide move away from courts allowing non-financial forms of pretrial release (such as release on own recognizance) to money bail, although this does vary substantially depending on jurisdiction. This chart illustrates the possible paths from arrest to pretrial detention. Almost all defendants will have the opportunity to be released pretrial if they meet certain conditions, and only a very small number of defendants will be denied a bail bond, mainly because a court finds that individual to be dangerous or a flight risk. The only national data on pretrial detention that we are aware of comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties series. Nationally, in 2009, 34% of defendants were detained pretrial for the inability to post money bail. This report focuses on this important population: those who are detained pretrial because they could not afford money bail.

Since the 1980s, there has been a significant, nationwide move away from courts allowing non-financial forms of pretrial release (such as release on own recognizance) to money bail, although this does vary substantially depending on jurisdiction. This chart illustrates the possible paths from arrest to pretrial detention. Almost all defendants will have the opportunity to be released pretrial if they meet certain conditions, and only a very small number of defendants will be denied a bail bond, mainly because a court finds that individual to be dangerous or a flight risk. The only national data on pretrial detention that we are aware of comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties series. Nationally, in 2009, 34% of defendants were detained pretrial for the inability to post money bail. This report focuses on this important population: those who are detained pretrial because they could not afford money bail.

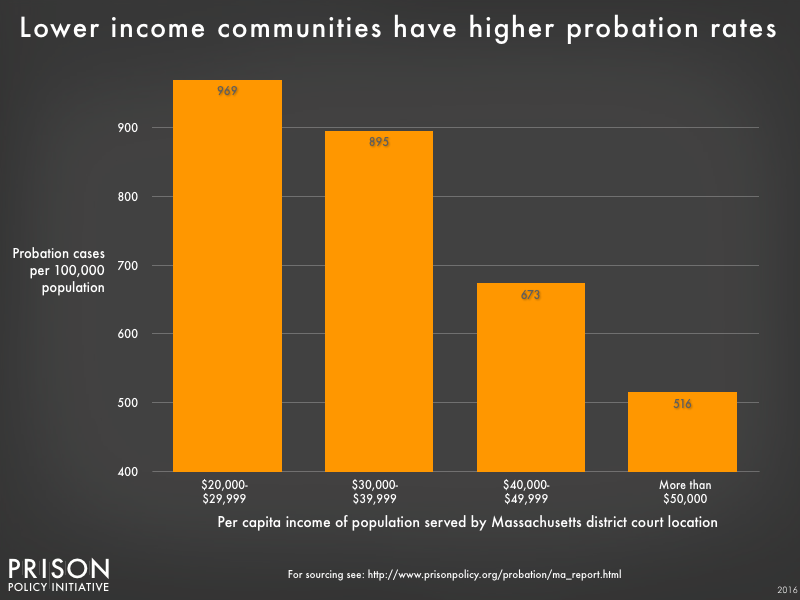

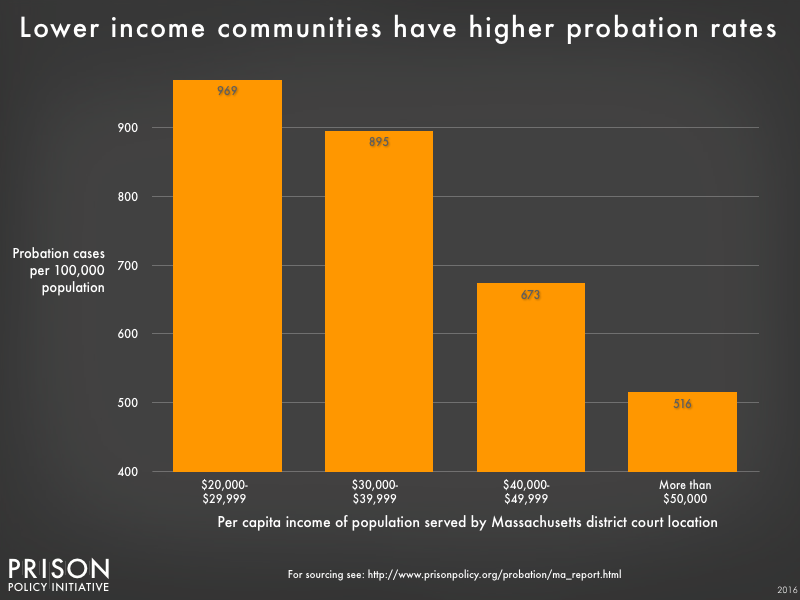

5. Probation fees

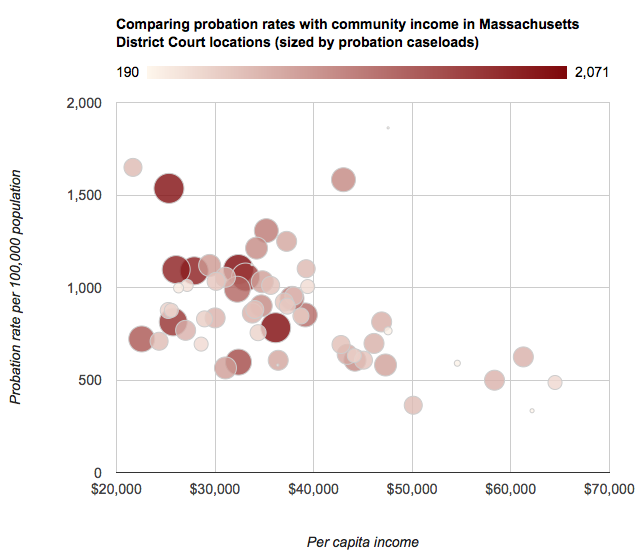

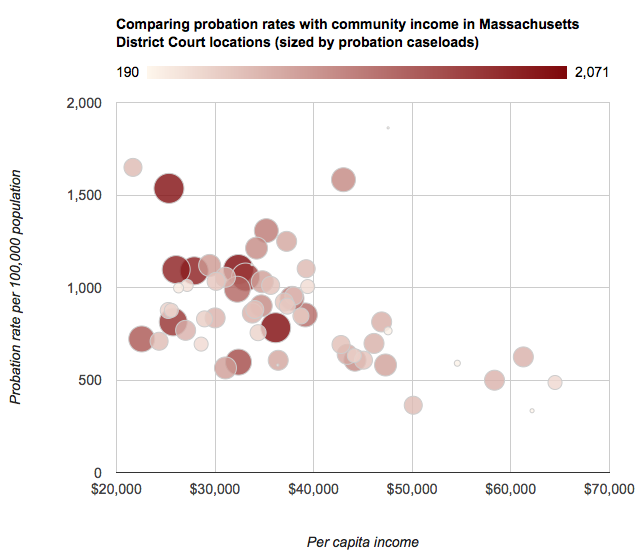

Court-ordered fines and fees have expanded dramatically as states have realized their revenue potential. But for the low-income people who are caught up in the system, these costs mean a greater risk of financial strain and even incarceration. In December, Wendy compared probation rates and incomes across Massachusetts and found that low-income communities are hit hardest by probation fees:

The District Court locations were grouped by the per capita income of the towns and cities they each serve. Probation rates are higher in court locations that serve populations with lower incomes.

The District Court locations were grouped by the per capita income of the towns and cities they each serve. Probation rates are higher in court locations that serve populations with lower incomes.

In the appendix of the report, we created a interactive scatterplot comparing each District Court’s probation caseloads and per capita income:

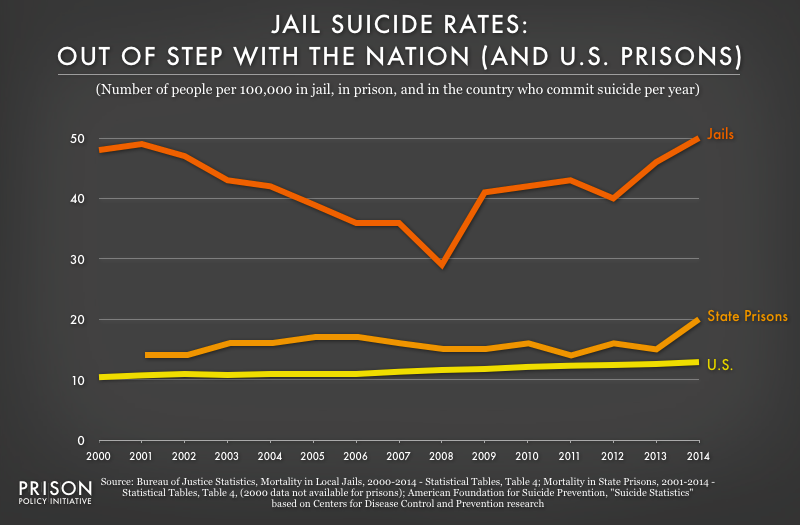

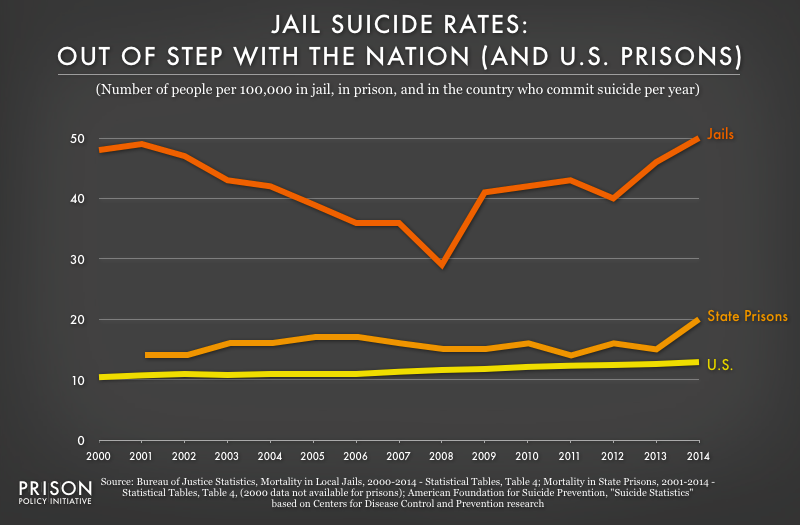

6. Shining a light on jail suicides

To cast light on the avoidable epidemic of jail suicides, we updated last year’s graph with a new article:

Bernadette’s article on the life-threatening reality of short jail stays also includes a graph illustrating groundbreaking data collected by the Huffington Post showing that most suicides occur in just the first few days of detention in jail.

7. A crime wave?

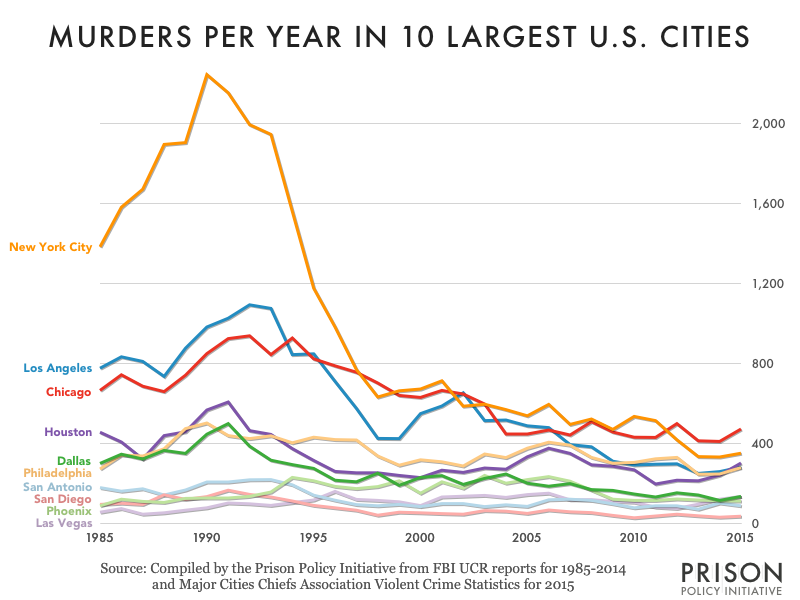

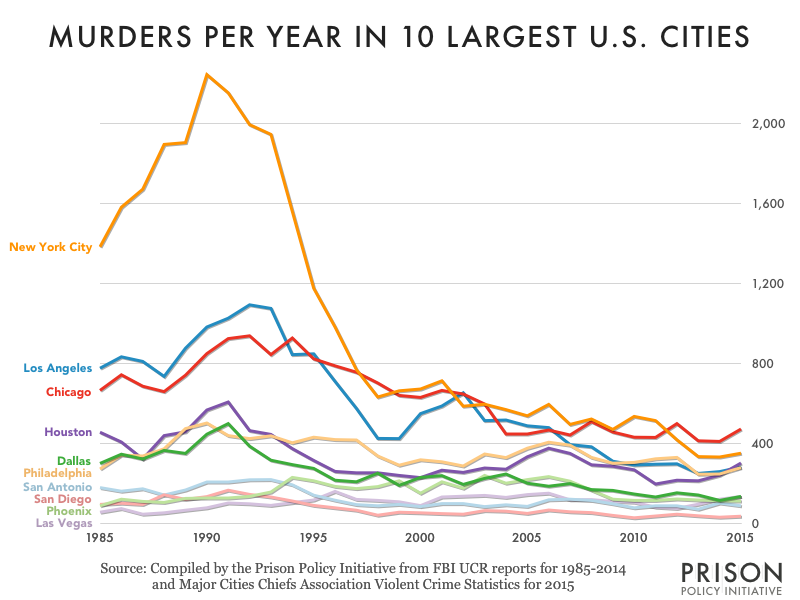

The President-elect says there is a crime wave. Is there? We looked:

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so we relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities.

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so we relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities.

For more on the need for city-specific crime data, see Wendy Sawyer’s analysis Making a mountain out of a molehill.

8. Public vs. private prisons

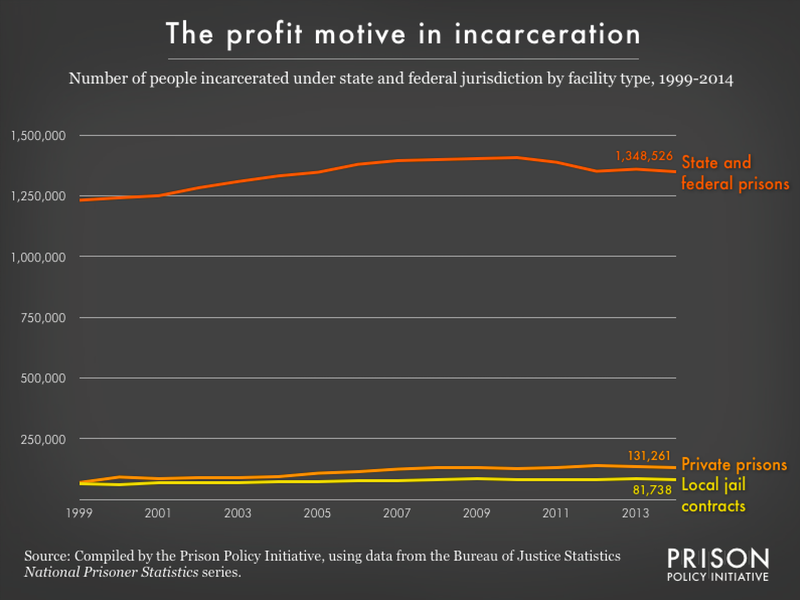

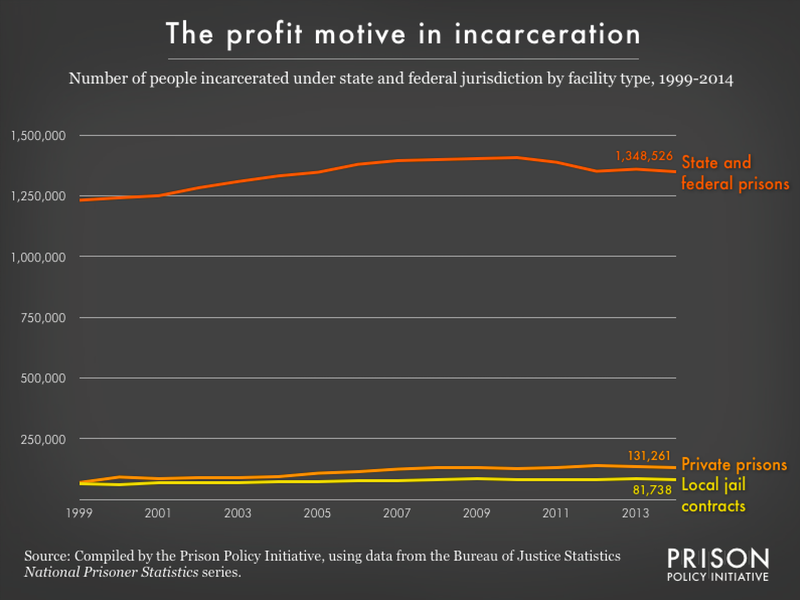

We’ve long argued that prisons owned and run by corporations that contract with state governments get far more attention than they deserve. But another huge provider of contractual prison services gets almost no attention whatsoever: local jails.

Since 1999, private prisons and local jails have housed roughly the same number of those serving state and federal prison sentences. But when those interested in justice reform talk about profiting off of mass incarceration, they almost always leave local jails out of the conversation.

Since 1999, private prisons and local jails have housed roughly the same number of those serving state and federal prison sentences. But when those interested in justice reform talk about profiting off of mass incarceration, they almost always leave local jails out of the conversation.

For more on this topic, see our article: Some private prisons are, um, public.

9. Beyond the crime bill

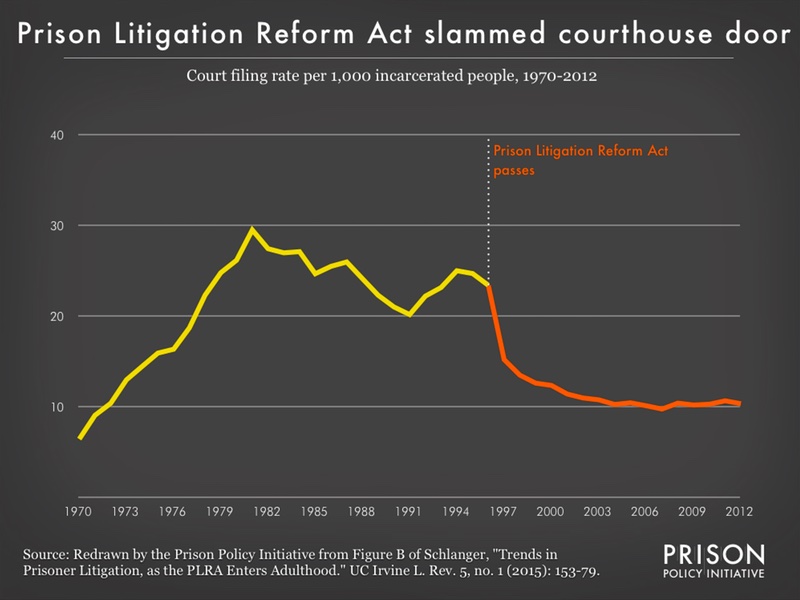

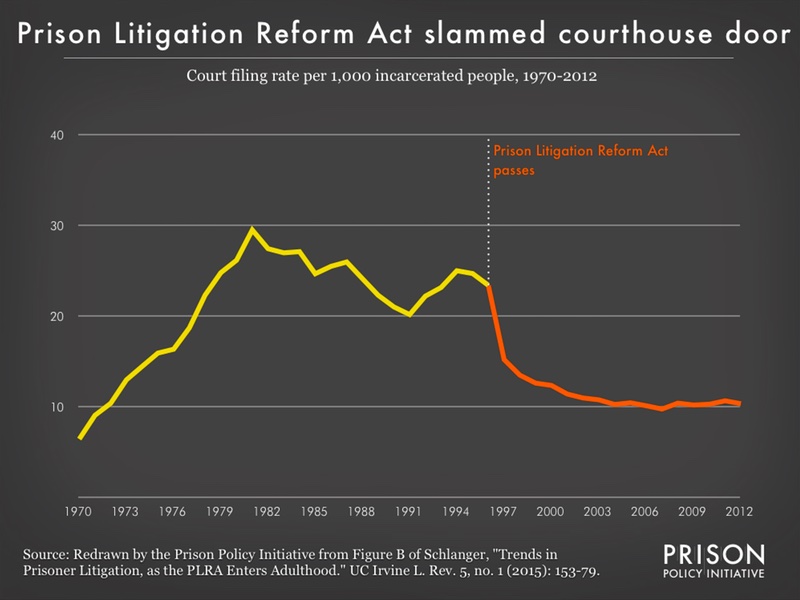

During the Democratic primary, many people blamed the Clintons for mass incarceration by pointing to the 1994 crime bill. But that was perhaps the least important of seven major bills. One of the most harmful, and the least discussed, was the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. In May, we made this data visualization of data collected by law professor Margo Schlanger for her article Trends in Prisoner Litigation, as the PLRA Enters Adulthood to make the magnitude of this change clear:

The filing rate by incarcerated people dropped significantly after the passage of the Prison Litigation Reform Act. And ironically, despite Congress’ fears of a prison lawsuits flooding the courts, this data that controls for the size of the prison population shows that in 1996, when the Prison Litigation Reform Act was passed, fewer lawsuits per 1,000 incarcerated people were being filed than during the ten year period of 1979-1988.

10. The Crippling Effect of Incarceration on Wealth

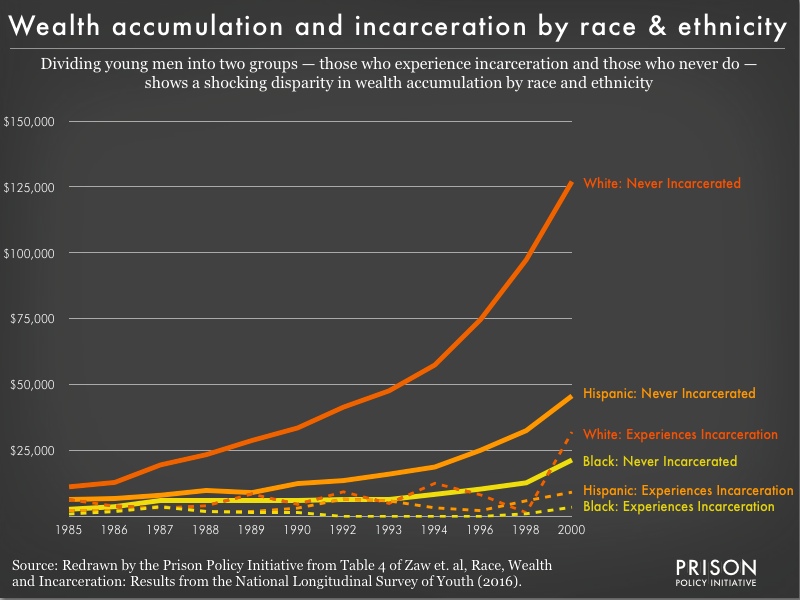

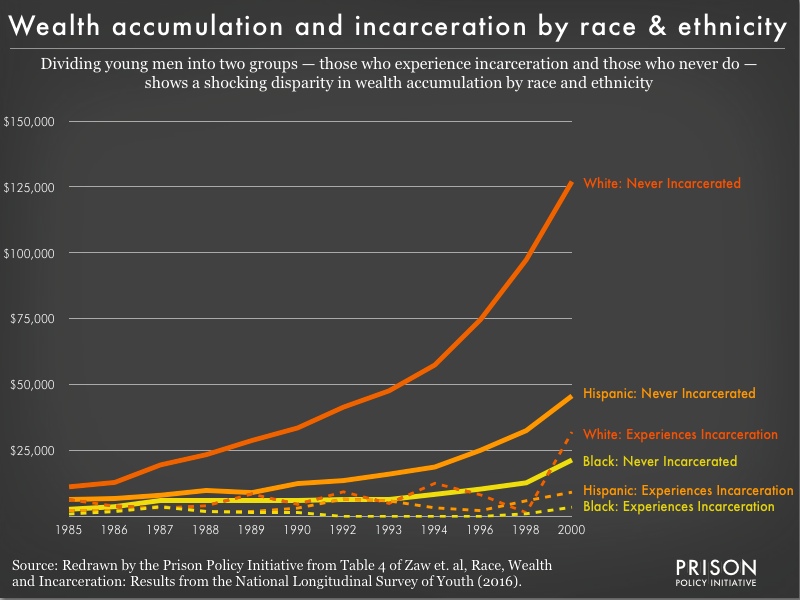

A fascinating study by Khaing Zaw, Darrick Hamilton, and William Darity Jr. shows that incarceration has a staggering effect on the accumulation of wealth over the course of a lifetime. To accompany our blog post on the original article, we made a data visualization of the data — including detail by racial group — published in the original article:

Our favorite criminal justice commentaries of 2016 that shined light on the too often forgotten areas of criminal justice reform

by Bernadette Rabuy,

December 29, 2016

This year, we were pleased to see writers, researchers, advocates, and public officials take a stand against mass incarceration. Here are some of our favorite examples of writing that pushed the envelope and shined light on the too often forgotten areas of criminal justice reform:

- Are We There Yet? The Promise, Perils and Politics of Penal Reform

By Marie Gottschalk

Prison Legal News

January 1, 2016

A comprehensive article by Marie Gottschalk, author of Caught, takes a critical look at the causes of mass incarceration and the various obstacles to reform such as the overemphasis on reforms that only affect those convicted of non-serious, nonviolent, and nonsexual offenses. Gottschalk’s article is useful for both those new to criminal justice issues and those looking to become more effective advocates for reform.

- The Meaning of Life Without Parole

By Clint Smith

The New Yorker

February 8, 2016

In this poetic piece, writer Clint Smith reminds readers of the humanity of his students who are serving long prison sentences in a Massachusetts state prison. Smith raises the urgent but difficult question: How, if at all, will criminal justice reform impact those convicted of violent offenses?

- Debtors’ Prison in 21st-Century America

By Whitney Benns and Blake Strode

The Atlantic

February 23, 2016

Writer Whitney Benns and attorney Blake Strode trace the pervasive practice of St. Louis counties locking people up for failure to pay fines and fees with the region’s troubled past. They explain how the St. Louis regional structure and longstanding racial segregation made the current practice of debtors’ prisons far from surprising.

- On pardons, Obama could go down as one of the most merciless presidents in history

By George Lardner Jr. and P.S. Ruckman Jr.

The Washington Post

March 25, 2016

In this oped, George Lardner Jr., a former Washington Post reporter, and P.S. Ruckman Jr., a professor and editor of the Pardon Power Blog, explain that despite President Obama’s Clemency Project 2014, Obama’s clemency record makes him one of the least merciful presidents in history. The oped also challenges the stringent criteria set forth by the Obama administration for commutation requests such as that applicants must have served at least ten years of their prison sentence.

- Why I refuse to send people to jail for failure to pay fines

By Ed Spillane

The Washington Post

April 8, 2016

In this groundbreaking oped, Ed Spillane, judge of College Station Municipal Court and president of the Texas Municipal Courts Association, shares why he refuses to lock poor people up for failure to pay fines. Instead, Judge Spillane urges other judges to be creative and consider alternatives like community service, payment plans, anger-management training, or even mercy.

- How to make mass incarceration disappear: John Pfaff, magical statistics and sentencing reform

By Scott Henson

Grits for Breakfast

April 11, 2016

Grits for Breakfast explores Fordham law professor John Pfaff’s counterintuitive and thought-provoking theories about mass incarceration, finding that they hold true for Texas: increased prison admissions, not longer sentences, have been driving mass incarceration since the late 90s. Henson concludes that, beyond prosecutorial reform, sentencing reform can still impact prison admissions such as by reducing common, low-level charges like drug possession or theft from felonies to misdemeanors.

- Bail bondsmen aggressively fight forfeitures

By Scott Henson

Grits for Breakfast

June 13, 2016

Henson uncovers a little-known truth: the bail bond industry often gets away with not paying bond money when defendants fail to appear in court. As a result, the bail bond industry gets to profit even without fulfilling its obligations.

- Why Prisoners Deserve the Right to Vote

By Corey Brettschneider

Politico

June 21, 2016

Corey Brettschneider, a professor at Brown University, writes that our country should go farther than giving the formerly incarcerated the right to vote; we should move in the direction of Maine and Vermont by allowing those currently behind bars to vote. Granting this right would allow us to listen to the incarcerated as we shape criminal justice policy and have a long-term impact on their political participation.

- Private prisons are not the problem: Why mass incarceration is the real issue

By Daniel Denvir

Salon

August 24, 2016

In the wake of the federal government’s announcement that it would phase out the use of private prisons to hold incarcerated people, Daniel Denvir uncovers the disappointing truth that a very small proportion of people in federal prisons would be affected. Denvir explains that the core of the problem of mass incarceration is that our society incarcerates too many people, and a clear majority of those people are in public prisons, not private.

- Mentally ill people in solitary confinement — we need to get them out

By Dave Mahoney

The Hill

August 30, 2016

Dave Mahoney, chief law enforcement officer of Dane County (Madison) Wisconsin, gets straight to the point: mentally ill people should not be in solitary confinement; it is nothing short of cruel. According to Mahoney, even jails in general are the wrong place for the mentally ill.

2016's most useful and under-exposed research that contributed to our movement's understanding of key issues in criminal justice.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 29, 2016

As 2016 comes to a close, the Prison Policy Initiative wanted to highlight some of our colleagues’ research that we thought was the most useful and the most under-exposed and contributed to our movement’s understanding of key issues in criminal justice:

-

Growing Up Locked Down

ACLU of Nebraska

January 2016

The psychological and physical harms of solitary confinement are so much worse for children who are still developing. The ACLU of Nebraska finds that the state overuses “the most inhumane correctional practices” of solitary confinement in every one of its juvenile justice facilities. Children there were placed alone in cells as punishment for minor offenses, like talking back or having too many books. The report calls attention to the “serious mental health impacts of solitary confinement for vulnerable youth” and the pressing need for policy reform.

- The Gavel Gap: Who Sits in Judgment on State Courts?

by Tracey E. George and Albert H. Yoon for the American Constitution Society

June 2016

In a democratic society, the courts should reflect the communities they serve. This report is the first to give a crystal clear picture of just how un-representative state court judges are by gender, race and ethnicity. To support further research and advocacy, it provides a new dataset of biographical information about state court judges. The report makes the case that if courts’ want to increase both their understanding of the communities they serve and public confidence in their decisions, courts must close these wide gender and racial “gavel gaps.”

- America’s Top Five Deadliest Prosecutors: How Overzealous Personalities Drive the Death Penalty

Fair Punishment Project

How is it possible that five prosecutors were responsible for 440 death sentences? The Fair Punishment Project details the bloodlust, racism and willful misconduct that made it possible for each of these notorious prosecutors to win scores of death penalty sentences. This report shows that the death penalty is an unusual punishment sought by a small number of zealots in just a few parts of the country.

-

Paying the Price: Failure to Deliver HIV Services in Louisiana Parish Jails

Human Rights Watch

March 29, 2016

Recognizing that the populations at risk of HIV and the incarcerated populations overlap, this report illustrates the urgent need for reform in Louisiana, which it describes as “‘ground zero’ for the dual epidemics of HIV and incarceration.” An accompanying video on the website gives voice to stakeholders by including interviews with formerly incarcerated people, HIV and health services providers, and representatives of the criminal justice system.

-

Punishment Rate Measures Prison Use Relative to Crime

Pew Charitable Trusts

March 23, 2016

This report looks beyond imprisonment to offer a new metric, “the punishment rate,” with which to gauge punitiveness. By comparing the size of prison populations to the frequency and severity of crime reported, rather than to the number of residents, Pew shows that the U.S. has become more punitive than traditional analysis suggests. Extending this analysis to individual states, Pew finds that Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming are all significantly more punitive than their imprisonment rates suggest.

- Race, Wealth and Incarceration: Results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Race and Social Problems

Originally published in Race and Social Problems, Vol. 8, Issue 1, 2016. The final publication is available at Springer Link

By Khaing Zaw, Darrick Hamilton, and William Darity, Jr.

March 2016

The authors of this study examine the wealth disparity between young men who experience prison and those who never do, using a survey that follows a group of young men for 27 years. They find that the men who are incarcerated have less wealth to begin with and, over time, accumulate only a small fraction of the wealth accumulated by their peers who are never incarcerated. (This is consistent with our findings that pre-incarceration incomes of incarcerated people are 41% lower than their peers.) We blogged about this report and produced two graphics based on it: The Crippling Effect of Incarceration on Wealth.

-

Get To Work or Go To Jail

By Noah Zatz, Tia Koonse, Theresa Zhen, Lucero Herrera, Han Lu, Steven Shafer, and Black Valenta at UCLA Labor Center

March 2016

Work at a terrible job, or go to jail. Those are the two choices for many people on probation and parole, as outlined by this research brief. Probation and parole conditions, as well as court orders to find work to pay court debts or child support, can force people to choose between bad (or unpaid) jobs and jail time. The threat of jail depresses labor standards and legal protections, which create cascading effects on all workers. The report provides estimates of incarceration for “failure to work” and links this threat to the practice of incarcerating people who fail to pay court fines and fees – something we discussed in our report on probation fees.

-

Roadblocks to reform: District Attorneys, Elections, and the Criminal Justice Status Quo

ACLU of Oregon

April 2016

District Attorneys have the power to make the justice system more progressive. But this report concludes that uncontested elections and appointments in Oregon lead DAs to block progressive criminal justice reform and maintain the status quo for their own self-interest. The ACLU makes a powerful case for why the national movement needs to pay more attention to DA races.

-

Unlicensed & Untapped: Removing Barriers to State Occupational Licenses for People with Records

by Michelle Natividad Rodriguez and Beth Avery with the National Employment Law Project

April 2016

Not only do people with criminal records face discrimination from employers, they also often face barriers in obtaining occupational licenses to work as a barber, hairdresser, health care worker, or teacher – even decades after their sentence ends. This report evaluates the effectiveness of state laws intended to ensure fairness for applicants with records and it provides recommendations for states, including a model law.

-

Louisiana Death Sentence Cases and Their Reversals, 1976-2015

Originally published in The Southern University Law Center Journal of Race, Gender, and Poverty, Vol. 7, 2016.

by Frank R. Baumgartner and Tim Lyman

April 26, 2016

An analysis of 241 death sentence cases in Louisiana since Gregg v. Georgia reinstated the death penalty in 1976 finds that the death penalty is still applied in discriminatory ways, and the frequency of reversals suggests the death penalty process is rife with errors and ultimately arbitrary in application.

-

Correcting Food Policy in Washington Prisons: How the DOC Makes Healthy Food Choices Impossible for Incarcerated People & What Can Be Done

Prison Voice Washington

From Washington state, a troubling example of how incarcerated people suffer when states try to cut costs. By eliminating all fresh, natural food in favor of processed products from a single prison food factory, the state has created “food deserts” in its prisons, failing to provide food that meet minimum standards for nutrition and increasing healthcare expenditures. This report shows how a nation that recognizes nutrition as a public health issue continues to neglect its incarcerated population.

-

Incarceration Trends

Vera Institute of Justice

December 2015

Vera’s Incarceration Trends project was technically launched in 2015, but it came out after we wrote last year’s list of best reports and it is too useful to ignore. A combination of two written reports and an interactive data tool, Vera’s research involved aggregating county-level data from 1970 to the present so that local incarceration rates can be compared over time and across jurisdictions. While also calling attention to racial and gender disparities, Vera’s Trends project is an incomparable resource that sheds historical light on the local face of mass incarceration.

Best investigative news reporters that find new ways to shed light on the complicated problems of the criminal justice system in 2016.

by Bernadette Rabuy and Wendy Sawyer,

December 29, 2016

Each year, investigative news reporters find new ways to shed light on the complicated problems of the criminal justice system. These are some of the in-depth stories and analyses that impressed us most in 2016:

-

Since Sandra: Here are the 815 (and counting) who have lost their lives in jail in the year after Sandra Bland died

Database by Shane Shifflett, Hilary Fung, and Alissa Scheller, with support from a large research and reporting team

Huffington Post

July 13, 2016

In the year after Sandra Bland’s death in a Texas jail, the Huffington Post scoured state and municipal data, news reports, press releases, and crowd-sourced reports to compile the details of over 800 deaths that occurred in jails nationwide. Disturbingly, they found that one-third of jail deaths occurred within the first three days, and suicide or apparent suicide was the leading cause of death. In this light, we see Sandra Bland’s death not as an aberration but as an example of too many jail fatalities.

-

The Scourge of Racial Bias in New York State’s Prisons

By Michael Schwirtz, Michael Winerip, and Robert Gebeloff

The New York Times

December 3, 2016

Racial disparities in arrests and sentencing are well documented, and The New York Times has now shown inequalities persist in the treatment of black men during their imprisonment. The Times analyzed 60,000 disciplinary cases from 2015 in New York State prisons, many of which are located in upstate New York and staffed by almost all white officers – even though blacks make up almost half of the prison population. The data gives clear evidence of racial discrimination against black and Latino men and appalling details of beatings and racial epithets from guards complete the picture.

- Machine Bias: There’s software used across the country to predict future criminals. And it’s biased against blacks.

by Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu and Lauren Kirchner

ProPublica

May 23, 2016

Can computers predict how likely defendants are to reoffend, reducing bias at crucial decision points? That is the hope with risk assessment tools, which produce scores that can influence decisions about bail and sentencing. But according to ProPublica’s analysis of the scores assigned to 7,000 people arrested in Broward County, Florida, the scores were slightly more accurate than a coin flip. ProPublica also found the tool is racially biased. One reason for this might be because it is difficult to construct a score that doesn’t include variables that correlate with race, like poverty and employment status. “Machine bias” demonstrates the danger of accepting risk assessments as impartial without adequately testing them and urges greater transparency in the use of risk assessments.

-

This small Indiana county sends more people to prison than San Francisco and Durham, N.C., combined. Why?

by Josh Keller and Adam Pearce

The New York Times

September 2, 2016

People in rural areas much more likely to go to prison than people in urban areas, even as crime has fallen in both rural and urban counties. The New York Times article demonstrates that unless criminal justice reform efforts focus on prosecutorial discretion, the impact of state reforms will be limited. The data provided also makes analyses of the variability in prison rates between counties in a specific state possible. For example, the Courier-Journal honed in on Kentucky counties and found in some counties, participants in drug treatment who experience a relapse automatically have their probation revoked whereas in other counties, first or second-time drug offenses get treatment rather than a conviction. The result is a patchwork of unequal justice, where the county prosecutor can make all the difference.

-

Thousands of Girls are Locked Up for Talking Back or Staying Out Late

by Hannah Levintova

Mother Jones

September/October 2016

Girls are increasingly impacted by the criminalization of low-level juvenile offenses: facing detention for minor infractions like skipping school or breaking curfew. Hannah Levintova investigated the gender biases that pervade the juvenile justice system and the girls who end up behind bars as a result.

-

Extreme Isolation Scars State Inmates

by Andy Mannix. Illustration by Clay Rodery

Star Tribune

December 4, 2016

The Star Tribune analysis of Minnesota Department of Corrections records from the past decade reveals that while other states like California and New York have worked to reduce the use of solitary confinement, Minnesota continues to put thousands of people in solitary confinement for long periods of time as punishment for minor offenses. The investigation includes straightforward but effective data visualizations that show what proportion of a person’s prison sentence has been spent in isolation.

-

After a Crime, the Price of a Second Chance

By Shaila Dewan and Andrew W. Lehren

The New York Times

December 12, 2016

Pretrial diversion is touted as a way to keep defendants out of crowded jails, lighten court caseloads, and connect people with needed services. But The New York Times finds that this “alternative” is often “pay to play,” with prosecutors offering pretrial diversion only to those who can afford high fees. Shaila Dewan and Andrew W. Lehren’s article offers illuminating examples and analysis, but the accompanying interactive makes the point simple: pretrial diversion is a rigged game.

-

Poor offenders pay high price when probation turns on profit

by Adam Geller and Sharon Cohen

Associated Press

March 12, 2016

Probation is not always the alternative to incarceration it seems. This is particularly true when governments outsource probation services to private probation companies. This investigation into the exploitative practices of private probation companies shows that in many places, probation is about profit, and people who can’t afford to pay fines and fees up front are trapped in a cycle of increasing debt and punishment.

-

Gutting Habeas Corpus: The Inside Story of How Bill Clinton Sacrificed Prisoners’ Rights for Political Gain

by Liliana Segura

The Intercept

May 4, 2016

Published when many people interested in criminal justice reform were talking about President Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, The Intercept’s Liliana Segura shines light on a lesser-known Clinton bill that has been a roadblock to justice, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. The bill made it harder for wrongly convicted people to prove their innocence, and Segura’s article explains the political machinations behind the effort to gut the ancient right of habeas corpus.

-

The bold step President Obama could take to let thousands of federal inmates go free

by Casey Tolan

Fusion

May 4, 2016

Fusion’s Casey Tolan tells the story of President Gerald Ford, who granted clemency to 13,603 people, thousands more than President Obama, despite Obama’s initiative to grant clemency. The article explains that President Obama could have more effectively used his clemency power by following in Ford’s footsteps and establishing a commission of lawyers, former elected officials, and generals who had one year to make clemency recommendations to the president. Tolan’s article is a great reminder of how history can inform the present.

New data reveals in 2015, the state and federal incarcerated populations declined by 2%

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 29, 2016

Today, the Bureau of Justice Statistics released its latest counts of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons and in local jails, and offered some good news. During 2015, the state and federal incarcerated populations declined by 2%, more than it has any year since the Bureau started tracking annual change in 1978. But relative to the exponential growth in the 1980s and 90s, the recent decline in the incarcerated populations has been frustratingly slow. Worse, the “record” decline is in large part the result of one-time changes in the federal system.

Almost half (40%) of this year’s prison population decrease is thanks to a dramatic drop in the federal prison population. In particular, a large-scale, one-time release of 6,000 non-violent drug offenders last fall accounts for 17% of the overall decline.

The current estimates from the Prisoners in 2015 and Jail Inmates in 2015 reports show that the much larger state prison and local jail populations have not fallen much since a short period of steady decline starting in 2008. In contrast to last year’s federal prison population, the combined state prison populations declined about 1% from 2014.

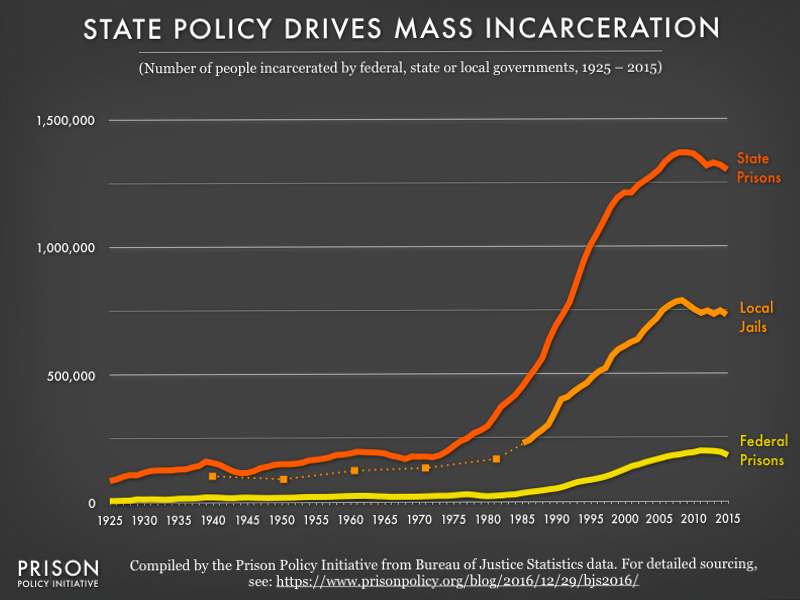

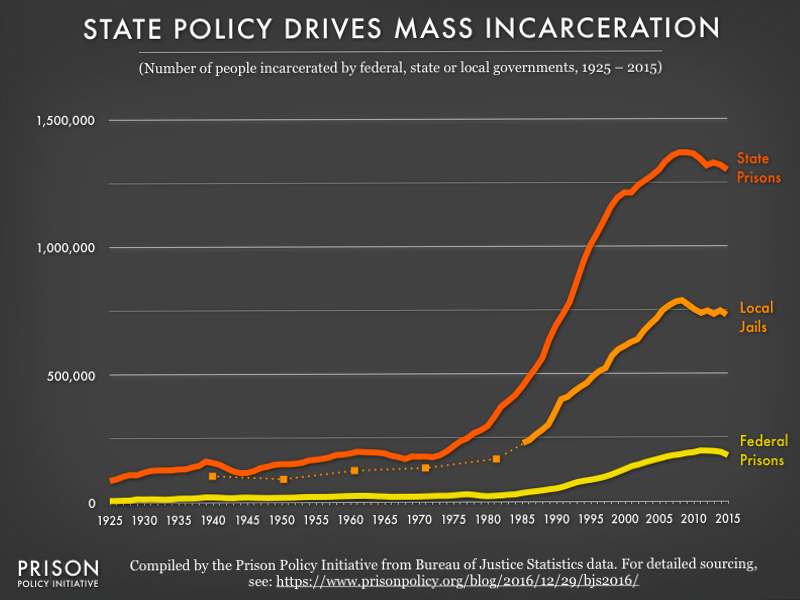

We updated our chart of incarcerated population counts over time to reflect the most recent estimates and demonstrate where the emphasis of our reform efforts needs to be: in the states.

As we noted in our original report on state prison growth, the vast majority of incarcerated people are locked up in state prisons. The justice policies of the 1980s and 1990s led to nearly three decades of mass incarceration, which was concentrated in state and local facilities. Of course, state policies vary significantly, so aggregating them masks the tremendous differences between the states with growing and shrinking prison populations.

Taken together, the state and local incarcerated populations dwarf the federal prison population. To reverse mass incarceration, then, we need to focus our attention on state and local policy.

Data sources for the graph

State prison populations:

Jail populations (midyear estimates, unlike state and federal yearend estimates):

- 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Historical Corrections Statistics in the United States, 1850 – 1984, Tables 4-1 and 4-2. (We used the columns marked “Census.” Jail data was not available for 1930.)

- 1983-1999: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 1999, Table 6.21

- 2000-2014: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates at Midyear 2014, Table 1

- 2015: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates in 2015, Table 1

Federal prison populations:

Aside from our recent reports, we have several new additions to our website worth highlighting.

by Peter Wagner,

December 28, 2016

Aside from our recent reports, we have several new additions to our website worth highlighting:

Eleven ideas for criminal justice reforms that are ripe for legislative victory in 2017.

by Peter Wagner,

December 28, 2016

This report has been updated with a new version for 2022.

With the 2017 legislative sessions about to start, it’s time to unveil our fourth annual list of under-discussed but winnable criminal justice reforms.

With the 2017 legislative sessions about to start, it’s time to unveil our fourth annual list of under-discussed but winnable criminal justice reforms.

The list is published as a briefing with links to more information and model bills, and it was recently sent to reform-minded state legislators across the country. The reform topics we think are ripe for legislative victory are:

- Ending prison gerrymandering

- Lowering the cost of calls home from prison or jail

- Repealing or reforming ineffective and harmful sentencing enhancement zones

- Protecting in-person family visits from the video visitation industry

- Stopping automatic driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving

- Protecting letters from home in local jails

- Requiring racial impact statements for criminal justice bills

- Repealing “Truth in Sentencing”

- Creating a safety valve for mandatory minimum sentences

- Immediately eliminating “pay only” probation and regulating privatized probation services

- Reducing pretrial detention

Let us know what you think of this year’s list. We look forward to working together to make 2017 a year of great progress for justice reform!

Jason Stanley's book -- the royalties of which support the Prison Policy Initiative -- is needed more now than ever.

by Peter Wagner,

December 27, 2016

There is a great review of the new paperback edition of board member Jason Stanley’s How Propaganda Works in today’s New York Times. Jason is generously donating the royalties from this book, his fourth, to the Prison Policy Initiative.

As Jason explains in his board interview on our blog, mass incarceration has become “embedded into the moral, political, and economic life of our country.” Today’s review points out that the book is even more timely now in light of the recent election:

In this volume (originally published in hardcover in 2015), Mr. Stanley does not grapple directly with Mr. Trump’s rhetoric, or the role that “fake news” played in the 2016 election. But his book does provide some useful insights into the dangers of propaganda — and its reliance upon mangled facts; false claims; and reductive, Manichaean storytelling. He observes that demagogic speech in democracies often uses language that purports to support liberal democratic ideals (liberty, equality and objective reason) in “the service of undermining these ideals.” He points out that propaganda frequently raises fears that are likely to curtail rational debate — for instance “linking Saddam Hussein to international terrorism” after Sept. 11 — and that it may play upon deeper prejudices toward ethnic or religious groups that rob “us of the capacity for empathy toward them.”

At this moment, when crime is at near-record lows but a President-elect who argues that crime is high and rising is about to be inaugurated, understanding how propaganda works will be key to both fixing our criminal justice system and preserving our democracy.

In 2016 we were honored to receive some great coverage of our work. Check out some of our favorites.

by Kim Cerullo,

December 27, 2016

One of our goals here at the Prison Policy Initiative is to engage the public in current criminal justice issues. Journalists who use our research in new, creative ways play a crucial role in that process. These were some of our favorite stories of 2016 featuring our work, starting with the most recent:

- Probation fees pose an undue burden

by The Boston Globe Editorial Board

The Boston Globe, December 13, 2016

The leading type of correctional control in the U.S. is not incarceration but rather probation. Probation may sound like a light punishment, but the substantial fines and fees burden families and make it harder for people to succeed. In Massachusetts, like many states, probation fees fall most heavily on those least able to afford them. This Globe editorial supports our report on probation fees and explains why we should not use “criminal justice as cash register.”

- New study critical of Virginia driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses

by Frank Green

The Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 10, 2016

Almost 39,000 safe drivers in Virginia lose their licenses each year. Why? Because Virginia is one of only 12 states in the country that still automatically suspend the driver’s license of anyone convicted of a drug offense, even if that offense had nothing to do with driving. Frank Green offers an in-depth analysis of our new report on the subject, which encourages states to opt out of this relic of the War on Drugs.

- In One N.H. Jail, Inmate Visits Don’t Look How You Might Think They Look

by Natasha Haverty

NHPR, December 5, 2016

If you have a loved one behind bars, there are more ways than ever to stay connected, including video visitation. But there’s a catch: when jails add video visitation, they often ban in-person visits. This New Hampshire Public Radio story puts a spotlight on Cheshire County Jail in New Hampshire, where these in-person visitation bans are tearing families apart.

- A Virtual Visit to a Relative in Jail

by Maya Schenwar

The New York Times, September 29, 2016

Video visitation can be a helpful way to keep families connected — as a supplement to in-person visits. What video visitation companies like Securus don’t advertise, however, is that in many places traditional visitation is banned. In this op-ed, Maya Schenwar builds on our report on video visitation with a description of her first video visit to her sister. With technical errors, glitchy screens, and a lack of eye contact, her experience makes it clear that video visitation doesn’t compare to the real thing.

- The Wrong Way to Count Prisoners

by The New York Times Editorial Board

The New York Times, July 16, 2016

When the Census counts people where they are incarcerated, rather than where they live, they inflate the populations of areas surrounding large prisons. The population boost leads to “prison gerrymandering” — giving undue influence to the political districts in those areas. Based on our analysis, this editorial explains why some states may be unable to prevent prison gerrymandering on their own and calls on the Census Bureau to take a stand for equality and fairness in the electoral process.

- The grotesque criminalization of poverty in America

by Ryan Cooper

The Week, May 16, 2016

At any given moment, 646,000 people are in American jails, with millions churning in and out of the system each year. Ryan Cooper builds on our report, Detaining the Poor, to make the case that forcing millions of people each year to spend unnecessary hours, days or months in behind bars just because they are too poor to make bail is “nothing less than a moral abomination.”

- The Prison-Commercial Complex

by Chandra Bozelko

The New York Times, March 21, 2016

A fee to create a calling account. A fee to add funds. A fee to get a refund. Those are just some of the ways that private companies put their hands into the meager pockets of incarcerated people and their families. Chandra Bozelko reviews our research on the prison telephone industry, the release card industry and the money transfer industry to bring attention to the hidden beneficiaries of mass incarceration.

Thinking of the U.S. criminal justice system as one system can be a mistake. There are 50 state systems, plus one in each of the approximately 3,000 counties and often separate systems in the approximately 30,000 municipalities. These differences matter a great deal.

Thinking of the U.S. criminal justice system as one system can be a mistake. There are 50 state systems, plus one in each of the approximately 3,000 counties and often separate systems in the approximately 30,000 municipalities. These differences matter a great deal.  People in local jails unable to meet bail are concentrated at the lowest ends of the national income distribution, especially in comparison to non-incarcerated people. As this graph shows, 37% had no chance of being able to afford the typical amount of money bail ($10,000) since their annual income is less than the median bail amount.

People in local jails unable to meet bail are concentrated at the lowest ends of the national income distribution, especially in comparison to non-incarcerated people. As this graph shows, 37% had no chance of being able to afford the typical amount of money bail ($10,000) since their annual income is less than the median bail amount.  Since the 1980s, there has been a significant, nationwide move away from courts allowing non-financial forms of pretrial release (such as release on own recognizance) to money bail, although this does vary substantially depending on jurisdiction. This chart illustrates the possible paths from arrest to pretrial detention. Almost all defendants will have the opportunity to be released pretrial if they meet certain conditions, and only a very small number of defendants will be denied a bail bond, mainly because a court finds that individual to be dangerous or a flight risk. The only national data on pretrial detention that we are aware of comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’

Since the 1980s, there has been a significant, nationwide move away from courts allowing non-financial forms of pretrial release (such as release on own recognizance) to money bail, although this does vary substantially depending on jurisdiction. This chart illustrates the possible paths from arrest to pretrial detention. Almost all defendants will have the opportunity to be released pretrial if they meet certain conditions, and only a very small number of defendants will be denied a bail bond, mainly because a court finds that individual to be dangerous or a flight risk. The only national data on pretrial detention that we are aware of comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’  The District Court locations were grouped by the per capita income of the towns and cities they each serve. Probation rates are higher in court locations that serve populations with lower incomes.

The District Court locations were grouped by the per capita income of the towns and cities they each serve. Probation rates are higher in court locations that serve populations with lower incomes.

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so we relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities.

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so we relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities. Since 1999, private prisons and local jails have housed roughly the same number of those serving state and federal prison sentences. But when those interested in justice reform talk about profiting off of mass incarceration, they almost always leave local jails out of the conversation.

Since 1999, private prisons and local jails have housed roughly the same number of those serving state and federal prison sentences. But when those interested in justice reform talk about profiting off of mass incarceration, they almost always leave local jails out of the conversation.