Punishing Poverty:

The high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts

a Prison Policy Initiative report

by Wendy Sawyer

December 8, 2016

Introduction

In Massachusetts, probation is a much bigger part of the correctional control “pie” than incarceration in prison or jail. Almost three out of four people under state correctional control are on some form of probation.1 If you are one of these 67,000 people, the state tells you probation is “an opportunity for you to make positive changes in your life,”2 allowing you to remain in the community, work, and be with family and friends instead of serving time in jail or prison. While this may sound like a great deal, it comes at a price.

Probation service fees in Massachusetts cost probationers more than $20 million every year.3 People are placed on one of two tiers of probation: supervised and administrative, and they are currently charged $65 and $50 per month, respectively.45 With an average probation sentence of 17-20 months,6 a Massachusetts resident sentenced to probation is charged between $850-$1,3007 in monthly probation service fees alone — on top of many other court fines and fees.8

Probation fees are relics of the 1980s. A result of “tough on crime” politics and a misguided attempt to plug a budget in crisis, probation fees do nothing to further the mission of probation services in Massachusetts. In fact, they work against probationers who struggle to meet the demands of their probation and the needs of their families.9 With money tight in the Commonwealth again, lawmakers may be tempted to hold on to probation fees for the revenues, but this policy is fiscally shortsighted and morally bankrupt.

A group of state lawmakers and judges has recently called for re-evaluation of court fines and fees,10 suspecting that these costs unfairly impact the poor and make it harder for people to succeed. This report analyzes state probation and income data to confirm those suspicions, and argues that the state should reverse its outdated and counterproductive policy.

Probation service fees are relics of misguided 1980s policymaking

“The concept of probation fees might seem more in keeping with the correctional philosophy of, say, Texas, than the more liberal Bay State,” admits a 1988 report on the subject to the state legislature.11 This crucial report, “Probation Supervision Fees: Shifting Costs to the Offender,” recognized that adding a financial penalty to probation would be anathema to most Massachusetts residents and policymakers. Nevertheless, the report concluded that the time was ripe for passing probation fees in Massachusetts. The combination of a state budget crisis and shift in public attitudes towards more punitive policies created the perfect conditions to pass the law:

“The state’s current fiscal woes are forcing a reevaluation of past policies with an eye towards raising new revenue…. At the same time, Massachusetts residents… are adopting an increasingly punitive attitude towards lawbreakers. In such an environment, the appeal of probation fees… might prove irresistible.”12

The lure of additional revenue did “prove irresistible” to the state: two weeks after that report endorsed probation fees, lawmakers enacted a monthly fee of 1-3 days’ net wages for almost everyone on probation.13

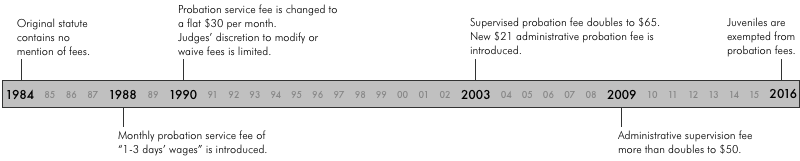

Once Massachusetts got the green light to charge probation fees, it did not hold back. Over twenty years, legislators expanded the fee and limited judicial discretion. In 1990, the fee was set at $30, instead of a day’s wages. In 2003 the legislature doubled it to $65 for supervised probation,14 and added the separate $21 administrative supervision fee.15 In 2009, facing budget cuts, the state increased the administrative supervision fee to the current $50 level.1617

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Poor communities foot the bill

In Massachusetts, poor communities foot a large part of the bill for the $20 million the state takes in probation service fees. Although critics of court fees have suspected that these costs unfairly impact the poor,18 until now, no reports specifically have addressed the relationship between probation and income. To see how economic status is related to probation, we analyzed probation caseload data19 at the most local available level — the 62 District Court locations — as well as income data for the population of the towns served by each court location.20 We compared total caseloads, probation rates, and per capita income for all 62 District Court locations and their jurisdictions.21

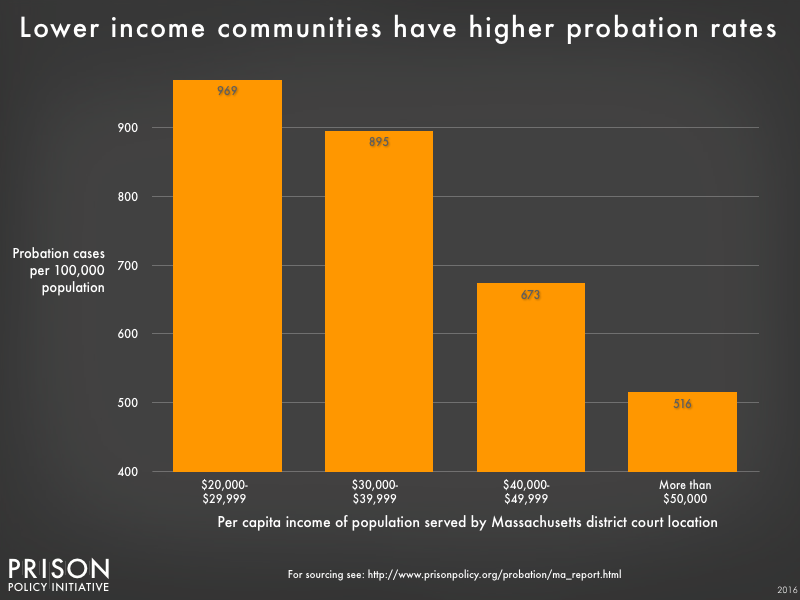

Our analysis confirms that probation rates are highest in the poorest parts of the state, and lowest in the wealthiest areas. People in the poorest District Court locations are on probation at a rate almost twice that of people in the wealthiest court locations. The courts serving the poorest populations have probation rates 88% higher than in those serving the wealthiest (see Figure 2). As incomes go up, probation rates go down, which means the people who can least afford additional fees are more likely to be on probation and expected to pay up every month. Probation fees function as a punishing regressive tax, wherein the state raises revenue by charging the poorest communities the most.

Figure 2. The District Court locations were grouped by the per capita income of the towns and cities they each serve. Probation rates are higher in court locations that serve populations with lower incomes. A comparison of the individual court locations’ probation rates and per capita incomes can be found in the Appendix.

Figure 2. The District Court locations were grouped by the per capita income of the towns and cities they each serve. Probation rates are higher in court locations that serve populations with lower incomes. A comparison of the individual court locations’ probation rates and per capita incomes can be found in the Appendix.

Looking at the individual court locations more closely, we find more evidence that probation disproportionately affects lower-income communities:

- 1/3 of all District Court probation cases are in ten court locations that serve areas where the average per capita income is 23% below the state average.

- There are huge disparities between the wealthiest and poorest cities in the state that impact probation. People in the five lowest-income court locations earn less than half what people in the five highest-income locations do, and their probation rates are almost twice as high.

- The most striking contrast appears between the Holyoke and Newton court locations. Holyoke serves the lowest-income people in the state, Newton the highest-income. Residents of Holyoke are sentenced to probation at a rate more than three times higher than in Newton. Because of its high probation rate, Holyoke handles 56% more probation cases than Newton, even though it serves less than half as many people. But Holyoke’s probationers can scarcely afford to pay; the average income in that area is $21,671, which is below the poverty threshold for safety net services such as reduced-price school lunches and food stamps.

Fee waivers: good in theory, not good enough in practice

In theory, Massachusetts judges should waive probation fees for defendants unable to pay the monthly fee.2223 In reality, this discretion is used infrequently and unevenly, making it an insufficient remedy for poor probationers.

The State Auditor’s report and a recent Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee report on the subject of court debt24 suggest that waivers are not granted consistently or often enough. If judges used their discretion consistently, we would expect more waivers to be granted in low-income court locations. But the Auditor’s sample showed that Wrentham and Concord granted almost four times more waivers than Fall River and Holyoke, despite serving much wealthier populations.25 The Senate committee found that although 60% of their sample’s defendants had previously been found indigent — and all of them ended up defaulting on court debts — judges offered waivers, community service, or other alternatives in only 47% of cases.26 Distressingly, both reports found that judges often do not document or even inquire into the ability of a probationer to pay fees.27

The inconsistent granting of waivers shows that they fail to provide relief to probationers. Given what we discovered about the correlation between poverty and probation, it is likely that few probationers can really afford any extra monthly fee.

Getting blood from a stone

Despite evidence that many probationers come from the poorest areas of the state, and the court’s ability to waive probation fees, the state manages to collect $20 million per year in fees. How is this possible?

The state uses its carceral power to pressure people to prioritize payment of fees over other needs and responsibilities.

The Supreme Court has said it is unconstitutional to incarcerate someone because they cannot afford to pay court ordered fines and fees.28 Nevertheless, the Senate committee report found that the state is incarcerating people for failure to pay court debts, without looking into their ability to pay.29 These judges know that people will do anything to avoid incarceration, so what better way to get them to pay than threatening — or ordering — jail time?

The shocking findings of the Senate report are less surprising when you consider that the threat of incarceration was always part of the state’s plan to collect fees. The 1988 report that served as the blueprint for Massachusetts’ probation fee policy suggests such a strategy of intimidation:

“Probation officers will have to exert pressure ranging from friendly persuasion to aggressive brow beating. Even the latter will sometimes prove ineffective and sanctions, including the threat of incarceration, are an essential element of successful fee programs.”30

It turns out the state, armed with the threat of incarceration, can in fact get blood from a stone. A better question is whether Massachusetts wants to be the kind of state that uses its courts, probation offices, and jails to squeeze its poorest residents.

Failure to pay probation fees: compounding consequences

The state cannot incarcerate a probationer for nonpayment of fines and fees if it determines the defendant is unable to pay them.31 But Massachusetts judges often do not concern themselves with the distinction between defendants who choose not to pay and those who are unable to pay.32 As we have discussed, they grant waivers infrequently and inconsistently, and neglect to conduct hearings on ability to pay before assessing fees or when people fail to pay. As a result, probation fees end up landing people in jail because they are too poor to pay.33

Incarceration is the most dramatic consequence of failure to pay fees, but there are many other, equally insidious penalties. When you fail to pay your probation fee:

- The court issues a default warrant to force you to return to court. This warrant comes with its own $50 fee; if you are arrested on the warrant, you pay a $75 fee.34 These fees exacerbate your existing court debt problem.

- Meanwhile, the RMV may suspend your license until the court clears the warrant and if your license is revoked, it will cost you another $100 to reinstate it.35 Without a license, it is even harder to work, manage family responsibilities, and meet the other conditions of your probation.36

- A judge may find you in violation of your probation conditions. As a result, the judge may change or add conditions of your probation. He or she may also consider failure to pay among other offenses to revoke your probation — a more circuitous route that also ends in incarceration.37

The costs of probation fees for courts and jails

For courts, probation fees mean extra work — and work that does not have a clear payoff in terms of protecting public safety or rehabilitating offenders. First, the legal requirement to have a hearing and document the finding of ability to pay takes up valuable court time, when it is conducted. Then there are the matters of collecting, processing, and reporting fees — and the inevitable problems stemming from people’s failure to pay fees. When a person gets a probation violation because they cannot pay, it means more work for the court, which issues the warrant, processes those fees, and requires yet another time-consuming hearing. The cycle continues from there.

When people are incarcerated for failure to pay fees, they “work off” their court debts at a rate of $30 per day.38 That is, $30 of their debt is forgiven for each day they are incarcerated. Yet it costs the state many times that amount to house someone in jail for a day.39 So, the state actually spends a significant amount of its own resources when it uses incarceration to pressure probationers to pay off their debts.

There is no current estimate of how much collection and processing of probation fees costs the state, let alone the additional court appearances and incarcerations that result from failures to pay.40 But probation fees — which are designed for cost-savings — undisputedly end up costing courts, probation officers, and jails resources that could be spent on more substantive issues.

The time cost is so significant that judges have tried to solve the problem by delegating decisions about fees to probation officers, despite the fact that such delegation is not allowed by law.41 These judges reason that the probation officer knows more about the offender’s real-time situation best, and giving officers more flexibility on this condition prevents cases from coming back to court unnecessarily.42 The judges’ solution shows that fees are not worth the courts’ time — policy makers should take note.

Probation fees defeat the purpose of probation

Probation fees aren’t just a burden for courts and probationers; they are in conflict with the stated goals of probation. Fees do not “increase community safety, support victims and survivors, and assist individuals and families in achieving long term positive change.”43 Once they are collected, fees go into the General Fund, not to services for probationers or victims of crime.44 And as we’ve discussed, they actually put more people in jail instead of keeping them out.

This policy is quite openly just about generating revenue from an already disadvantaged population. Probation fees were consistent with the priorities of late 1980s tough-on-crime politics. In today’s more rehabilitative, service-oriented probation model, they make no sense.

The American Probation and Parole Association itself poses the central question for policymakers: “Correctional fees can be big business,” they reflect, “but is it the business we’re supposed to be in?”45

Recommendations for Massachusetts

State legislators should:

- Recognize that the people in the criminal justice system are among the state’s poorest, and amend all court fines and fees policies to reflect this fact. Legislators should construct laws with the presumption that these costs will present hardships for most defendants that will impede their success.

- Stop using the courts as revenue generators for the state. Pressuring courts to collect fines and fees to fill in gaps in the budget leads to serious conflicts of interest. The legislature has recognized this conflict in the past but still needs to resolve it by divorcing state revenues from justice policy.46

- Change the current statute to stop charging monthly probation fees to provide immediate, substantial relief for the 67,000 state residents on probation. These fees are a burden to probationers already under financial strain, do not contribute to the mission of probation services, and bog down court processes.

- If legislators are unwilling to eliminate probation fees, they should make the following changes to improve the current probation fee policy:

- Lower probation service fees, make payments more flexible, or both. Lowering fees and allowing partial or one-time payments will make it easier for probationers to pay fees, reducing the number of violations from failure to pay, and will ease some of the financial burden on probationers.

- Exempt people on post-release supervision from paying probation service fees. As the Massachusetts Trial Court Fines and Fees Working Group points out, these fees are an unjustifiable impediment for probationers facing the additional challenges of re-entry.47

- Amend the law so that judges only assess probation fees in cases where a positive determination of ability to pay has been documented. Given the increased likelihood that probationers come from low-income areas, policymakers should presume that probation fees would present a hardship.

- If legislators leave the current fee waiver system in place as the sole means of relief, they should institute a clear and broad standard for fee waiver decisions. Comm. v. Henry48 offers some guidance, but current practices still lead to uneven and inadequate granting of fee waivers. The broadest standard should be adopted, so that judges can use their discretion to waive fees in all cases where fees will present a hardship.

- Change the law to allow judges to use their discretion to delegate fee decisions to probation officers. Delegating this decision to probation officers will empower probation officers to make appropriate decisions for each client, and will save the court time that would be wasted in further hearings about ability to pay when probationers fail to pay fees.

As long as the law mandates probation fees, judges should:

- Ensure counsel is provided in all hearings that result from failure to pay fees, without additional counsel fees. As the Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee report found, only half of the defendants who were incarcerated for failure to pay fines and fees had counsel at hearings that resulted in their incarceration. Providing counsel would protect probationers from punishment for inability to pay fees.49

Together, the legislature and judiciary should:

- Create more alternative probation conditions beyond community service and incarceration for people who cannot afford to pay fees. Offer services that are more aligned with the priorities of probation to help people achieve long-term change and improve public safety.50

- Evaluate the collective impact of the numerous court-imposed fines and fees, and revise the current schedule of potential fees to ease the burdens of payment and collections on defendants and court departments. A commission should be established to conduct a comprehensive review of the dozens of existing court fines and fees. A model for this evaluation process exists in Massachusetts; in 2010 a commission investigated the impact of additional inmate fees, which estimated the revenue, administrative and collection costs, and impact on the residents who would be paying.51

Probation should:

- Collect and report more data related to probation and court-imposed fines and fees. Apart from the yearly Auditor’s report, which is based on a limited sample of court locations and cases, there are no comprehensive reports on probation fee assessments, waivers, or collections. Massachusetts, unlike many states, does not collect or report much probation data in general.52 With improved data and reporting, the state could better assess probation policies, including the effects of probation fees.

Conclusion

The time to challenge court fines and fees is now. Massachusetts lawmakers have signaled some responsiveness to calls for reform, with a recent amendment ending fees for juveniles. The state Senate, at least, has probation fees in its sights: this year, the Senate passed its budget bill53 with amendments making all probation fees discretionary and prohibiting judges from punishing people who fail to pay fees with incarceration, probation violations, or probation extension. Unfortunately, this version of the bill did not make it to the Governor’s desk.

It must be tempting for lawmakers to continue to defend probation fees as a necessary evil. But we know too much about the real costs of probation fees in Massachusetts to let this policy stand. We know that probation disproportionately impacts poor communities, and that the current waiver system doesn’t adequately protect them. We know that poverty is being punished; people are locked up for court debts, including probation fees.

The state should not view the courts as a piggy bank. Justice cannot be served when the courts are given perverse incentives to ensnare more people in the web of court fines and fees. And while probation fees aren’t substantial enough to make or break the state budget, they are enough to break the bank for thousands of probationers.

Appendix

The Appendix has a detailed comparison of each District Court location’s probation and income data, as well as a list of the towns served by each of the 62 District Court locations. It is available at https://www.prisonpolicy.org/probation/ma_appendix.html

Acknowledgements

This report was supported by a generous grant from the Gardiner Howland Shaw Foundation and by the individual donors who support the Prison Policy Initiative’s ongoing research and advocacy work.

Our research on income and probation would not have been possible without the assistance of many other researchers, advocates, and court officials. Our colleagues at the Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center provided invaluable assistance with the research process, especially Babatunde Aremu, Marshall Clement, Monica Peters, and Cassondra Warney. Shira Diner from the Committee for Public Council Services also graciously offered her insights on probation. Chief Justice of the Trial Court Paula M. Carey, Chief Justice of the District Court Paul C. Dawley, and Deputy General Counsel of the District Court Sarah W. Ellis provided critical links to data and shared the work they are doing on fines and fees. Deputy Commissioner of Programs Michael Coelho and his staff at the Office of the Commissioner of Probation provided the probation data used in our analysis. Bill Cooper provided data analysis of poverty data and probation in Massachusetts. Jake Mitchell of the Young Professionals Network created the interactive scatter plot in the Appendix. Bob Machuga created the cover. Finally, the author would like to thank the rest of the Prison Policy Initiative staff for their feedback and support throughout the research and drafting process.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to demonstrate how the American system of incarceration negatively impacts everyone, not just the incarcerated. In 2008, the Easthampton, Massachusetts based organization demonstrated the inefficacy and disparate impact of sentencing enhancement zones in Massachusetts’ Hampden County. In 2014, the Initiative reported on the harms caused by an outdated federal law that automatically suspended driver’s licenses for drug offenses unrelated to driving, helping Massachusetts lawmakers understand the issue and opt-out of the law in 2016. The organization also conducts national-level research and provides online resources giving activists, journalists and policymakers the tools they need to participate in setting effective criminal justice policy.

Footnotes

The Council of State Governments Justice Center, Massachusetts Criminal Justice Review, Working Group Meeting 1: review of justice reinvestment process and proposed scope of work (January 12, 2016), 37. https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/MA_Working_Group_Meeting_1.pdf ↩

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. “Frequently Asked Questions — What is Probation?” Commonwealth of Massachusetts Website, 2016. http://www.mass.gov/courts/court-info/probation/ocp-faq-gen.html#WhatisProbation ↩

Massachusetts Trial Court Fines and Fees Working Group, Report to Trial Court Chief Justice Paula M. Carey (Boston: November 17, 2016), p. 6. http://www.mass.gov/courts/docs/trial-court/report-of-the-fines-and-fees-working-group.pdf ↩

These general categories are used to distinguish the two fee tiers. For probation service purposes, probation cases are broken down into more specific categories: “Risk Need and ORAS” (Supervised), Administrative, Driving Under the Influence of Liquor (DUIL), and Pretrial Supervision. Juvenile cases are not included in this report because they are no longer assessed monthly probation service fees; this change was instituted as part of the 2017 state budget on July 1, 2016. See 2016 Mass. ALS 133, 2016 Mass. Ch. 133, 2015 Mass. HB 4450, available at https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2016/Chapter133 . ↩

Each of these probation service fees includes a $5 victim services surcharge, which goes to the General Fund along with the monthly probation service fees. Massachusetts Trial Court, District Court Department, “Potential Money Assessments in Criminal Cases” (Boston: 2015), p. 3. http://www.mass.gov/courts/docs/courts-and-judges/courts/district-court/potential-moneyassessment-criminalcases.pdf. ↩

The Council of State Governments Justice Center, Massachusetts Criminal Justice Review, Working Group Meeting 2: Key statutory frameworks, sentencing policies, and practices that impact incarceration and community supervision in Massachusetts (April 12, 2016), p. 45. https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/MASecondPresentation.pdf ↩

This range was calculated by multiplying the lowest probation fee ($50) by the low end of the range of the average sentence (17 months) to get the low of $850, and by multiplying the higher fee ($65) by the high end of the range (20 months) to get $1300. ↩

For a schedule of all “Potential Money Assessments in Criminal Cases” published by the Massachusetts Trial Court District Court Department, see: http://www.mass.gov/courts/docs/courts-and-judges/courts/district-court/potential-moneyassessment-criminalcases.pdf ↩

Ralph D. Gants, Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court, Annual Address: State of the Judiciary (Boston: October 20, 2015), p. 9. http://www.mass.gov/courts/docs/sjc/docs/speeches/sjc-chief-justice-gants-state-of-judiciary-speech-2015.pdf ↩

American Probation and Parole Association, “Issue Paper — Supervision Fees,” American Probation and Parole Association Website, January 2001. https://www.appa-net.org/eweb/Dynamicpage.aspx. ↩

Charles R. Ring, Massachusetts Legislative Research Bureau, Probation Supervision Fees: Shifting Costs to the Offender (Boston: July 7, 1988), p. 8. https://archive.org/stream/probationsupervi00ring/probationsupervi00ring_djvu.txt. ↩

Ring, 1988, p. 2. ↩

The report was submitted to the Legislative Research Council on July 7, 1988. The amendment to M.G.L ch. 276 S 87A, instituting probation fees, was adopted July 26, 1988. ↩

Probationers are divided into two categories based on the level of required interaction with parole officers: “supervised probation” involves more interaction with a probation officer and typically is a longer sentence than administrative probation, which requires minimal reporting. Suzanne M. Bump, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Office of the State Auditor, Trial Court — Administration and Oversight of Probation Supervision Fee Assessments (Boston: January 13, 2016), p. 5. https://www.mass.gov/doc/trial-court-administration-and-oversight-of-probation-supervision-fee-assessments/download. ↩

From 2003 onward, probation fees included a “victim service surcharge,” which was $5 for supervised probation and $1 for administrative probation in 2003, and then $5 for both levels of probation as of 2009. ↩

When the fiscal year 2010 budget was passed, it required the Trial Court to increase its collections of probation supervision fees by $3 million for a total of $26 million. At the same time, it more than doubled the administrative probation fee, likely in an effort to enable the Trial Court to collect the additional revenue. Until fiscal year 2013, it should be noted, the Trial Court’s budget depended partly on the fees it collected, so there was pressure on the Court to maximize fee collections. Massachusetts Trial Court Fines and Fees Working Group, 2016, p. 4. ↩

For the full history of the statute, see: 1984 Mass. Acts ch. 294, S 1; 1988 Mass. Acts ch. 202, S 27; 1990 Mass. Acts ch. 150, SS 343, 344; 2002 Mass. Acts ch. 300, SS 2A, 13; 2003 Mass. Acts ch. 26, SS 2, 510; 2009 Mass. Acts ch. 27, SS 99, 100; and 2016 Mass. Acts ch. 133, S 121. ↩

Gants, 2015, p. 9. ↩

See Appendix for a table including probation caseloads for each court location for January 2016. Probation caseload data provided to the author by the Office of the Commissioner of Probation. ↩

For population and per capita income, we used the 2014 American Community Survey 5-year estimates for towns from Table B01003. We grouped all of the state’s towns and cities by the District Court location that serves them, and aggregated the town data at this grouped court location level. See the Appendix for a list of the towns served by each court location.

A few notes about our sample: The Boston Municipal Court (BMC) locations were not included in this analysis; they handle cases similar to the District Court’s but serve the cities of Boston and Winthrop. The BMC was excluded because those courts serve neighborhood areas that are incompatible with the town-level Census data used for our analysis. The Superior Court Department was excluded because those locations serve entire counties. The Juvenile Court Department was excluded because as of 2016, juveniles no longer pay probation service fees. The District Court Department (our sample) is responsible for about 69% of probation cases and 85% of probation service fee revenue, so our analysis includes most of the relevant population (Bump, 2016, p. 5). However, because we excluded probation cases from these other courts, our probation rates understate the total number of people on probation in each area. ↩There are 62 District Court locations, not including the Boston Municipal Court, but the Gardner and Winchendon locations are in the same building and their caseloads are combined for probation reporting. For this analysis, the population, per capita, and poverty data for these two departments were combined into one “Gardner/Winchendon” location so as to match the data from Probation. For a complete list of the towns and cities served by each court location, as well as a detailed comparison of probation and income data for all court locations, see the Appendix. ↩

In Massachusetts, probation fees can be reduced or waived by a judge with written documentation of a finding-of-fact hearing that determines the probationer cannot pay the monthly fee. In place of fees, probationers perform at least one day of community service per month for supervised probation and four hours per month for administrative. However, the number of people performing community service instead of paying a fee is actually declining, down 26% from 2011-2014 (Bump, 2016, p. 6), despite the relatively stable probation population:

Year Count of total yearend probation population in Massachusetts 2011 68,615 2012 68,673 2013 67,784 2014 68,274 Thomas P. Bonczar, Count of total yearend probation population (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics). Generated using the Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) — Probation at www.bjs.gov on November 16, 2016.

The decrease in community service numbers may be because courts feel pressured to assess and collect fees as a source of revenue. Another reason could be that judges recognize that many people have to meet many conditions of their probation, such as intervention or treatment programming, and fitting in community service can create more hardship (Bump, 2016, p. 16).

↩There are no firm standards by which judges decide to waive fees, but recent case law suggests guidelines, which are subject to interpretation by a judge. In a case determining whether to impose restitution (which are different from probation fees but are another source of court debt), “the judge must consider the financial resources of the defendant, including income and net assets, and the defendant’s financial obligations, including the amount necessary to meet minimum basic human needs such as food, shelter, and clothing for the defendant and his or her dependents.” Comm. v. Henry, 475 Mass 117 (2016) ↩

Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, Fine Time Massachusetts: Judges, Poor People, and Debtor’s Prison in the 21st Century (Boston: November 7, 2016.) It should be noted that while the report did not focus on probationers, 19% of the cases they reviewed involved probation fees, and 70% involved default-related fees which can apply to probationers who fail to pay probation fees (p. 12). ↩

Waiver information comes from the State Auditor’s report. Bump, 2016, p. 14. Wrentham and Concord courts have the highest per capita incomes (Wrentham: $43,396; Concord: $61,463) of those in the Auditor’s sample, and Fall River and Holyoke have the lowest (Fall River: $25,321; Holyoke: $21,671). In the sample of cases tested by the Auditor, Wrentham waived fees in 21 of 60 cases, Concord 10 of 44 cases, Fall River 3 of 60 cases, and Holyoke 5 of 40 cases. ↩

Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 22. ↩

While both reports found problems with the inconsistency with which waivers were granted, they reached very different conclusions, which illustrate the tension between the state’s desire to maximize revenue and its ideals of fairness and compassion. The State Auditor criticized judges for waiving probation fees without consistently providing written findings of fact to support each waiver. The report suggested that probation fee revenues could be even higher if judges did not waive fees without documenting inability to pay. Bump, 2016, p. 13-14.

The Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, in contrast, criticized the overwhelming failure of judges (in 94% of cases in its sample) to inquire about ability to pay when incarcerating defendants for failure to pay court debts. This report argues that by failing to look into whether failure to pay was “willful” rather than due to inability to pay, judges have created a “debtor’s prison” situation in Massachusetts. Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 13, 22. ↩Beardon v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1983) ↩

Judges skirt the issue of whether this confinement is unconstitutional by ignoring the question of whether a defendant is unable to pay their debt or choosing not to pay. Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 16. ↩

Ring, 1988, p. 19. ↩

See Beardon v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660 (1983); Commonwealth v. Gomes, 407 Mass. 206 (1990); and Commonwealth v. Henry, 475 Mass. 117 (2016). ↩

Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 16. ↩

Looking into the sources of criminal court debt, the Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee found 19% of the sample in the had been ordered to pay monthly probation fees; 70% had been ordered to pay default-related fees, such as the default warrant fees charged to probationers when they fail to pay probation fees. Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 12. ↩

Massachusetts Trial Court, District Court Department, “Potential Money Assessments in Criminal Cases,” p. 3. ↩

Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles, “Suspensions — Criminal Defaults,” Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles Website, 2016. https://www.massrmv.com/SuspensionsandHearings/Suspensions/CriminalDefaults.aspx ↩

The president of the Massachusetts Sheriffs’ Association, points out, “Just like you or me, an individual who has been convicted… needs his or her driver’s license to accomplish a whole host of activities: cash a check…, apply for a job, apply for housing, apply for transitional assistance, provide evidence of identity, travel, and more.” Steven W. Tompkins, “Ending Driver’s License Suspension for Drug Offenders,” CommonWealth Magazine, January 11, 2016. https://commonwealthmagazine.org/criminal-justice/ending-drivers-license-suspension-for-drug-offenders/

Also see the Prison Policy Initiative’s report on driver’s license suspensions as a collateral consequence of drug laws. Leah Sakala, Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving (Easthampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, May 14, 2014). https://www.prisonpolicy.org/driving/ ↩Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee believes that failures to pay court debts are important factors in decisions to incarcerate people for probation violations. Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 17, FN 14. Charles R. Ring, in his report endorsing probation fees, expected that judges would be unlikely to revoke probation simply for failure to pay probation fees, but that failure to pay fees could combine with other factors and result in probation revocation. Ring, 1988, p. 21. ↩

Although fees have increased steadily since the 1980s, the per diem credit has not increased since 1987. M.G.L., ch. 127, S144. The Massachusetts Trial Court Fines and Fees Working Group suggests that the per diem credit be “revised to reflect current inflation rates when considering the value of a day of incarceration.” They calculate that the $30 figure from 1987 would be worth $64.21 today, and point out that minimum wage was $3.35/hour in 1987, versus $10/hour today. Massachusetts Trial Court Fines and Fees Working Group, 2016, p. 25. ↩

A Vera Institute of Justice report gives a “reported average daily cost per inmate” of $143.72 for Hampden County Jail in Springfield, MA. Christian Henrichson, Joshua Rinaldi, and Ruth Delaney, The Price of Jails: Measuring the Taxpayer Cost of Local Incarceration (Vera Institute of Justice: May 2015), p. 27. https://www.vera.org/publications/the-price-of-jails-measuring-the-taxpayer-cost-of-local-incarceration ↩

A national study conducted in 1990 (when many states, including Massachusetts, adopted probation fee laws) found that costs to probation offices and courts vary up but can be up to 18% of the revenue generated. Dale Parent, Recovering Correctional Costs Through Offender Fees (Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Justice, 1990), p. 17.

A more recent study reported lower collection costs in the range of 4-6% of revenues in Orange County, California, Montgomery County, Texas, and the Arizona Fines/Fees and Restitution (FARE) program; however, it should be noted that this report focuses on best practices in improving collections, so these programs may have been selected as best-case-scenarios. John T. Matthias and Laura Klaversma, Current Practices in Collecting Fines and Fees in State Courts: A Handbook of Collection Issues and Solutions, Second Edition (National Center for State Courts Court Consulting Services, 2009), p. 92.

No studies included estimates of collection costs for Massachusetts. ↩Bump, 2016, p. 16. ↩

Bump, 2016, p. 18. ↩

Quote from the mission statement of the Massachusetts Probation Service. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, “Court Information — Office of the Commissioner of Probation,” Commonwealth of Massachusetts Website, 2016. http://www.mass.gov/courts/court-info/probation/

For further discussion of the conflict between the “proper roles of courts and correctional agencies” and the collection of fines and fees, see: Alicia Bannon, Mitali Nagrecha, and Rebekah Diller, Criminal Justice Debt: A Barrier to Re-entry (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, 2010), p. 30-31. ↩Massachusetts Trial Court, District Court Department, “Potential Money Assessments in Criminal Cases,” p. 3. ↩

American Probation and Parole Association, “Issue Paper — Supervision Fees,” 2001. ↩

Until fiscal year 2013, the Trial Court’s budget depended on revenue collected from probation fees, so that a shortage in collections triggered an equal decrease in the Court’s budget. The judiciary recognized this conflict of interest: “The judiciary opposed the practice of ‘retained revenue’ budgeting because it effectively imposed production quotas on the fees that the court departments collected, creating the appearance of a conflict between the interest of justice and the interests of the court system. As former Chief Justice Margaret Marshall stated in budget testimony, ‘no one assessed a fine by the court should have to wonder whether interests of justice or of institutional preservation motivated the penalty.” The legislature responded to this conflict by eliminating the Trial Court Retained Revenue Account and directing revenues to the General Fund. Massachusetts Trial Court Fines and Fees Working Group, 2016, p. 4.

Although the Trial Court’s budget is no longer directly tied to its collections, the state continues to pressure courts to collect fines and fees. For example, the 2015 budget included $500,000 for a “revenue maximization unit” to boost collections at district court locations that were underperforming (Mass. Acts ch. 165 S 2), and the State Auditor’s report suggests that the District Courts can and should be collecting more revenues. Bump, 2016, p. 13. ↩Massachusetts Trial Court Fines and Fees Working Group, 2016, p. 24. ↩

Comm. v. Henry, 475 Mass 117 (2016) ↩

Massachusetts Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 23. ↩

As the Senate committee report suggests, services like restorative justice programs, intimate partner violence prevention, and traffic safety courses are more tailored to the needs of probationers and better address public safety concerns. Massachusetts Senate Post Audit and Oversight Committee, 2016, p. 23. ↩

Special Commission to Study the Feasibility of Establishing Inmate Fees, Executive Office of Public Safety and Security, Inmate Fees as a Source of Revenue: Review of Challenges (Executive Office of Public Safety and Security: July 1, 2011). ↩

For example, Massachusetts only reports data on the total population and sex of probationers to the Bureau of Justice Statistics Annual Probation Survey, and fails to report characteristics including race, sentence type (felony/misdemeanor), most serious offense, and status of supervision. ↩

2016 Mass. SB 2305, available at https://malegislature.gov/Bills/189/Senate/S2305. ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.