The Wireless Prison: How Colorado’s tablet computer program misses opportunities and monetizes the poor

Colorado's tablet program foreshadows a potential new paradigm in corrections, shifting numerous communications, educational, and recreational functions to a for-profit contractor; and making incarcerated people and their families pay for services that are commonly funded by the state.

by Stephen Raher, July 6, 2017

In 2010, Apple made waves when it introduced the iPad. Over the last seven years, consumers have been busy trying out ever-more-powerful mobile devices; meanwhile, correctional facilities have been quietly experimenting with letting incarcerated people use limited-function electronic tablets inside prisons and jails. Correctional administrators are often resistant to change, but after a few tentative forays, some prison systems are beginning to adopt tablet programs on a larger scale.

A recent Denver Post article reports that the Colorado state prison system has awarded a contract to prison communications giant GTL (formerly Global Tel*Link) for a tablet program that will eventually be deployed in all the state’s prisons.

The Colorado Department of Corrections (DOC) is somewhat of an early adopter of emerging communications technology. For several years it has offered electronic messaging, an email-like service that allows people in prison to send and receive messages using a proprietary, fee-based platform operated by a contractor. Colorado DOC’s electronic messaging program isn’t perfect, but its rollout was notable for giving people a new communication option. The tablet program, on the other hand, foreshadows a potential new paradigm in corrections, shifting numerous communications, educational, and recreational functions to a for-profit contractor; and, at the same time, making incarcerated people and their families pay for services, some of which are now commonly funded by the state.

What makes the Colorado/GTL contract especially frustrating is that it could have been an innovative step toward providing incarcerated people with useful technology. Experts who have studied government technology contracting warn that projects often fail because details are not sufficiently thought through. The Colorado DOC seems to have walked down this familiar path by focusing largely on its own financial interest without giving much thought to the user experience or the financial impact on incarcerated people and their families.

The basic details

In broad brushstrokes, the GTL contract works like this: GTL installs wifi networks in all Colorado prisons, and provides enough tablets so that each person in the DOC system can have one. The tablet itself is free, but using it is generally not.1 Tablets can be used to make phone calls, send electronic messages (similar to email, but with fewer features), play games, or listen to music — all for a price.

Incarcerated customers pay for tablet functions under one of two pricing models. First, phone calls and electronic messaging are charged based on usage: phone calls are currently 11¢ per minute,2 and electronic messages are 49¢ each. Games, music, and other digital content are provided under a subscription system, however the Colorado/GTL contract lacks many important details. For example, the contract allows GTL to offer games through “tiered monthly subscriptions, priced from $5.00 to $15.00 per month,” but does not specify what makes the tiers different from each other. GTL can also offer digital music for “up to $19.99 per one month subscription.” That price tag is eye-popping, given that free-world services like Spotify and Google Play offer subscriptions for half the cost.3

Even worse, GTL has the power to unilaterally change most customer prices at any time for any reason. Although the Colorado contract locks in phone rates, all other charges are subject to change at GTL’s discretion.

GTL’s website allows loved ones to pay for services that an incarcerated child or spouse may need, but it doesn’t give family members any meaningful details about the service they are paying for (among other things, this means that a family member who has questions about what they are paying for, or wants to help an incarcerated love one troubleshoot technical problems is unable to do so). Because of GTL’s parsimonious release of information, there are plenty of questions about how the tablets work, and not a lot of readily available answers. Nonetheless, a few observations are possible just based on the limited information available.

Phone calls on mobile devices make sense

Allowing people to make phone calls from their tablet is basically a good thing.4 Instead of using a shared phone in a public area (probably with other people waiting in line), callers can now talk in more private locations. In return for getting rid of the waiting line, DOC agreed to raise its per-call time limit to at least 60 minutes (from the current 20), allowing for longer conversations and — not coincidentally — more revenue for GTL.5 Even though tablets can be used for phone calls, they cannot be used for video visitation. This may be due to either technical or security limitations.6

Many of GTL’s pricing models are unfair to customers

As noted previously, GTL’s prices for music subscriptions are nearly double those found in free-world services, with no obvious reason for the disparity. Indeed, there is reason to suspect that GTL’s catalog of streaming music is significantly smaller than that of a regular streaming service — GTL offers tablets in the Pennsylvania prison system, where it advertises that users can choose from approximately three million songs (in contrast, as of a couple of years ago, Spotify and Apple both had upwards of thirty million songs in their respective catalogs).7 But it is difficult to draw any definite conclusions about the comparative value of a GTL music streaming subscription because the company does not make basic information publicly available.8

As for games, it isn’t clear why DOC allowed GTL to offer these only by subscription when outright purchase could make more economic sense for customers. Of course, most popular games are downloadable for free; but this model depends on advertising revenue and may well be unworkable in a prison environment. Even so, most app games available for purchase are priced between $1.50 and $8, which makes GTL’s $5-15 per month pricing seem exploitative. As an example, for two months’ of subscription fees (at $15/month) one could simply buy the eight most popular paid games in the Google app store.

Finally, the pricing for electronic messaging doesn’t make sense — the contract sets rates at 49¢ (the cost of a first-class stamp), and specifies that prices will automatically increase whenever postage goes up. As we discussed in our report on electronic messaging, tying prices to postage rates has no economic basis. Parity with first-class postage is clearly an attempt by GTL to frame itself as a cost-neutral equivalent to mail, even though there are numerous reasons why mail is often a better communications channel for incarcerated people.

Using tablets to eliminate postal mail would be a disaster

Some have already suggested that tablets can completely supplant postal mail. The Denver Post published a shortsighted editorial making just such an argument. This is a dangerous line of thinking. Not only is postal mail a critical tool for people who lack computer skills or internet access, but people often use mail to maintain human connections in innumerable ways that cannot work in the stripped-down, inflexible environment of GTL’s electronic messaging platform.9 A no-mail policy would stamp out such everyday human connections as a handwritten note from a parent, or a loving scribble from a child. Moreover, publications of numerous types and formats (magazines, catalogs, tax forms and instructions, newspaper clippings, greeting cards)10 can easily be sent through the mail but cannot be accommodated by plaintext messaging systems.

Tablets could be an important rehabilitative tool, but not when GTL puts profit above service

GTL has been quick to emphasize the potential of tablets to provide access to educational programming. But the fine print in the Colorado/GTL contract provides some interesting insight into how this might work.

The original contract required GTL to “supply educational content … that is generally suitable for the inmate population based on industry standards … except, however, Company shall not be required, and [Colorado DOC] shall assume, any cost of delivering such content to inmates that exceeds in any year a retail value of $500,000.”11 This awkwardly written provision seems to anticipate that GTL would provide up to $500,000 worth of educational content per year. But, since the very same paragraph specifies that all “content shall be provided on subscription bases,” it appears that GTL would recoup the costs of this content through subscription fees.

In March 2016, the DOC and GTL amended the contract to remove the language concerning educational programming. Why the change? The amendment itself says that the amendment was brought about by the FCC’s order capping phone fees, and that “[r]eference to the educational content delivery cost in excess of $500,000.00 annually is hereby suspended until such time as it can be re-negotiated pending any new FCC mandates or call volume increases which are determined enough to offset costs.”12 Put more simply: the original contract allowed GTL to charge high phone rates and use the resulting profits to produce programs that incarcerated customers would then have to pay to access. When the FCC forced GTL to lower its phone charges,13 that profit center suddenly became less of a cash cow.14

Education in prison has historically been viewed as a public service that helps prepare people for reentry and assists in the management of a safe facility. It is also part of the social contract; so much so that the Colorado legislature created a prison education program in 1990, declaring that education’s role in reducing recidivism was critical enough that the state should adequately fund literacy, cognitive, and vocational education programs.15 The structure of the Colorado/GTL contract suggests that the DOC is ready to discard the public-service model of education that utilizes in-person instruction, opting instead for a technology-driven, user-funded model that dispenses knowledge from a screen and leaves students to fend for themselves. Other companies have gone further and argued that prisons should eliminate libraries in favor of offering ebooks via tablets (for a fee, of course).

Contractually, the deck is stacked in GTL’s favor

Although the Colorado/GTL contract spells out pricing for incarcerated customers, these provisions are somewhat hollow because GTL can unilaterally change prices (other than phone rates) at any time. The real meat of the contract is in the parts that specify what GTL is promising to provide. The answer: not as much as one might expect.

GTL sidesteps responsibility for repairing its products and will pull out if too many tablets are broken

GTL is contractually obligated to provide enough tablets so that every person incarcerated in the DOC should get one. But what happens when tablets stop working? As anyone who owns a smart phone or iPad knows, devices often develop problems. Add in the unfriendly prison environment, and high failure rates are virtually certain.16 So, did Colorado DOC negotiate a carefully structured contract that ensures people will have reliable hardware to access the services they so dearly pay for? No.

First of all, the contract flatly excuses GTL from any responsibility for repairing tablets that are “damaged or destroyed by willful act, as determined in [GTL]’s discretion”.17 It’s predictable that GTL wouldn’t want to repair intentional damage, but giving the company absolute discretion to decide when damage is intentional creates a power dynamic ripe for abuse. Plus, at the most basic level, how will GTL be able to tell how a tablet was damaged when it doesn’t have onsite staff? The Colorado/GTL contract didn’t have to be set up this way. Indiana’s prison system is currently considering a tablet program, and the DOC there has stated as part of the bid process that “[t]he cost for broken or defective devices is the responsibility of the vendor.”18

Even in the somewhat unlikely event that GTL applies the intentional-damage provision in a reasonable manner, it still isn’t obligated to do much: the contract specifies that GTL will replace or repair malfunctioning tablets one time per customer,19 and even then GTL’s replace/repair liability is capped at 5% of deployed tablets per year.20 And if GTL has to repair/replace more than ten tablets in any one housing unit during a year, it can simply cancel the tablet service at that unit.21

Based on data from the free world, GTL’s expectations about failure rates seem overly optimistic. A 2012 report found that 10% of second-generation iPads failed in the first twelve months after purchase. A more recent report from February 2017 that looked at all mobile devices (tablets and phones) concluded that Apple devices had an overall failure rate (across models) of 62%, while Android devices failed at a rate of 47%.22 Of course, GTL isn’t using iPads or Android tablets, but rather is using a proprietary product called “Inspire,” which it designed itself. Given that GTL presumably has less robust and sophisticated engineering resources than Apple, it seems likely that a failure rate of less than 5% is not realistic.

If people don’t buy enough over-priced content, GTL will stop the service

Another disappointingly one-sided provision in the Colorado-GTL contract allows GTL to back out of the contract if it doesn’t make as much money as it hopes to. Specifically, “if there is insufficient revenue to warrant the continuation” of the tablet service at any given prison, then GTL can cancel service at that facility. This structure is troubling for a number of reasons. First, it sets up the possibility some prisons would have tablet services and others wouldn’t — creating a patchwork of inequality within the DOC system. Also, because DOC stands to gain from the tablet program (both in terms of the annual payment it receives and having a new incentive to use while “managing” incarcerated populations), it’s not hard to envision situations in which DOC actively works to increase GTL’s revenue: Are game subscriptions down? Cut down on recreation time. Not enough revenue from vocational education videos? Eliminate in-person classes.

Follow the money: built-in incentives for DOC to favor GTL over the public

The tablet program is one component of a multi-part contract between GTL and Colorado DOC that covers phone service, tablets, video visitation, and money transfers. As with most contracts that grant a monopoly for goods or services marketed to incarcerated people, the Colorado/GTL bundled-services contract creates a steady revenue stream and then divides it between the DOC and the contractor.

Prison telecom contracts have long been criticized because of the sizeable kickbacks given to prison systems in the form of a “commission” on revenue collected by the telecom provider. The Colorado/GTL contract provides a monetary reward to the DOC, but it is not framed as a percentage of revenue; instead, GTL agrees to pay the DOC a flat payment of $800,000 per year.23 The payment amount is subject to annual renegotiation.

Interestingly, in 2015, the Colorado legislature passed a law that prohibits the DOC from receiving phone commissions “except as much as is necessary to pay for calling costs and the direct and indirect costs incurred by the department in managing the calling system.”24 Because the law only covers phone service — and the GTL contract encompasses non-phone services like tablets — it’s difficult to tell whether the $800,000 payment complies with the legislature’s directive.

The contract specifies that in exchange for the $800,000 annual payment, GTL “shall have the exclusive right to collect and retain all revenue generated from the services supplied through this Agreement.” Those revenues are generated through a variety of fees levied on people who can least afford them. The user fees are troublesome not just because they are higher than comparable services in the free world, but also because of the predatory nature of the system. One of the most common complaints about life in prison is the overwhelming boredom. Thus, selling entertainment to incarcerated people is somewhat like selling food to hungry airplane passengers: there’s one source, and the provider can charge what it wants, regardless of quality. Captive customers desperate to fight monotony will be more willing to pay GTL’s inflated prices. But realistically, most people in prison lack the requisite funds because incarcerated people have disproportionately low incomes and they are not adequately compensated for their in-prison labor. Thus, the simple fact of the matter is that family members (who themselves are more likely to be low income) will end up footing the bill, adding to the financial stress of a population that is already stigmatized merely by virtue of association.

In one important respect, prison telecom vendors have more power than an airline selling in-flight meals. At least so far, airlines haven’t figured out a way to prevent passengers from bringing their own food. In contrast, GTL can partner with the Colorado DOC (who — remember — is receiving a cut of the profits) to prohibit other lower-cost alternatives. For example, if revenues from electronic messaging are too low, DOC could ban postal mail. Not enough music subscriptions? DOC could prohibit incarcerated people from owning radios. Just because the DOC hasn’t taken these steps yet does not mean it won’t in the future. If the tablets prove to be popular, they could start to be viewed (either by incarcerated people or prison staff) as a quasi-necessity. In such a scenario, GTL will have considerable leverage because the contract provides GTL with numerous ways to pull out of the deal.

No, really — follow the money: under GTL’s pay to pay system, families pay twice

The economics of the Colorado/GTL contract are about more than who reaps the profits. It’s also important to consider the basic mechanics of how incarcerated people and their families pay for the games and music hawked by GTL. Not only do families end up paying for tablet services, but they also fork over additional money just to pay GTL.

GTL’s pay to pay system is needlessly complicated and seem to be intentionally designed to deprive relatives of what meager consumer protections may be available. Specifically, GTL is downplaying the availability of trust fund transfers in favor of advertising its own prepaid service options.

The Colorado DOC’s webpage hardly contains any information about the tablet program. In fact, the only apparent reference on the site is the instruction: “To message an offender with a GTL tablet visit https://web.connectnetwork.com/ to create an account. GTL messaging service lets you send messages to an offender in just a few simple steps.” Following that link brings the user to a homepage that brags about lots of products, but is not specific to Colorado. If the customer goes to the list of GTL facilities and selects Colorado DOC, they finally get a page listing most Colorado services:

The menu shown above curiously omits one financial service: trust fund deposits, a money transfer service that is also facilitated by GTL, under a contract with Colorado DOC. Making a trust fund deposit isn’t free (it’s subject to fees that are roughly comparable to those charged for GTL’s “Debit Link” program), but in some ways it provides more protections for customers. First of all, if a mother sends her son money through a trust fund deposit, the son basically gets the same thing: money (or, more precisely, the ability to draw on money in an account held by the state). The son can then use the trust fund money to pay for phone calls or music subscriptions. Or, if he has more pressing needs, he could use the money to pay medical copays or buy toothpaste at the commissary. If he needs something that isn’t sold by the commissary, he may be able to purchase it from an outside mail order vendor by requesting a money order. On the other hand, if mom prepays for phone calls or buys “Link Units,” then her son can only use the money for that narrowly designated purpose — if she buys $10 worth of Link Units and her son then needs to make a $10 phone call or pay for a doctor’s visit, she’ll have to send more money.

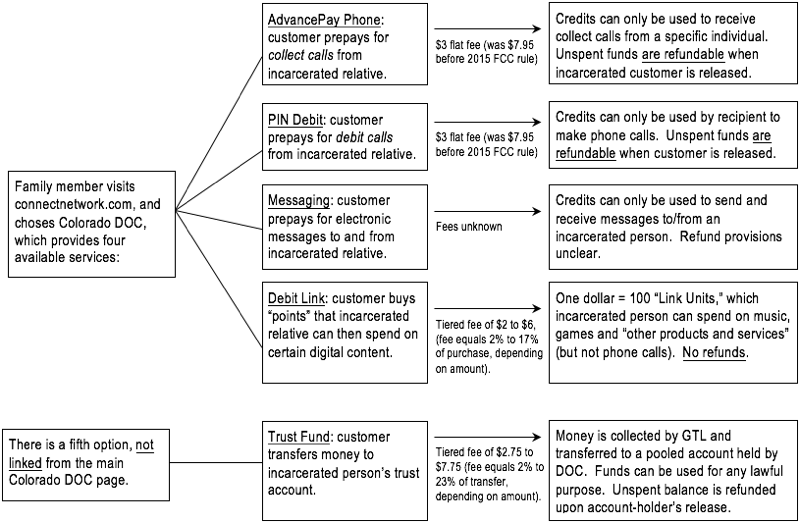

Another important distinction between the various types of payment channels is refund provisions. Trust funds can be withdrawn at any time, and are refunded upon someone’s release from prison. In contrast, prepaid services are subject to a complicated patchwork of rules. Money spent on prepaid phone calls is refundable only upon the incarcerated customer’s release. Link Units are especially confusing: if mom buys Link Units directly for her son, that money is never refundable. But if mom sends money to her son’s trust fund account, and he uses that money to buy Link Units, then the unused credits are refundable upon his release. These important details are never clearly explained on GTL’s website25 (and remember that the trust fund transfer feature is difficult to find). The following diagram shows the maze of fees and policies that family members are faced with if they want to financially help their loved ones in Colorado’s prison system.

Many of the options available to people who want to send money to loved ones in Colorado prisons limit the ways funds can be used, and may not provide refunds of unused credits upon release. GTL’s main Colorado DOC page points visitors toward prepaid services and does not even list trust fund deposits, which are refundable and offer incarcerated people the most flexibility.

Many of the options available to people who want to send money to loved ones in Colorado prisons limit the ways funds can be used, and may not provide refunds of unused credits upon release. GTL’s main Colorado DOC page points visitors toward prepaid services and does not even list trust fund deposits, which are refundable and offer incarcerated people the most flexibility.

The fine print

Also disappointing is the fact that the Colorado/GTL contract explicitly says that incarcerated users will be forced to agree to GTL’s “terms and conditions” before they can use their tablet,26 but it doesn’t seem that anyone at DOC bothered to read the terms and conditions when negotiating the contract. Even if somebody did read the terms and conditions, they aren’t incorporated into the final contract between GTL and DOC, which means that GTL can change them at any time. The terms and conditions for incarcerated users aren’t publicly available, so it’s hard to know what people are being forced to agree to. But odds are it isn’t good, given the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy that GTL imposes on non-incarcerated customers. These two documents (which form the basic contract governing customers’ rights) are written with needlessly complex and unfamiliar language, and contain provisions that are designed solely to make life easier for GTL at the expense of its customers.

To begin with, the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy are inexcusably long, totaling over 7,000 words (almost as long as a standard form mortgage, which clocks in at about 8,800 words). Among the troublesome provisions that customers must agree to are: relinquishing the right to participate in a class action lawsuit,27 an overly broad and one-sided indemnification provision,28 and consenting to GTL’s sharing customer data with data analytics firms29 (which raises a host of privacy and fairness concerns).

One particularly glaring example of the state’s double standard concerns binding arbitration (wherein a customer gives up their right to go to court). The contract between Colorado DOC and GTL specifies that “[t]he State of Colorado does not agree to binding arbitration…. Any provision to the contrary in this Contract or incorporated herein by reference shall be null and void.”30 In contrast, the Terms of Use forced upon end-users contains an arbitration clause buried in the fine print.31

What next?

Other states will follow

Colorado is an early adopter in the realm of prison tablets, but other corrections systems have similar programs or are are looking to follow suit:

- Pennsylvania uses GTL’s tablet system, although the features available there seem limited to electronic messaging and music (users must also pay $147 per tablet).

- South Dakota has selected GTL to roll out tablets later this year.

- Indiana has accepted bids for a tablet system in its prison system, and hopes to award a contract later this year.

- The Alabama prison system may be soliciting bids later this year.

- In addition, several larger jails also offer tablets.

GTL is not the only company in this market. One of GTL’s competitors, JPay (now a subsidiary of Securus Technologies) claims to have tablet service in nine state prison systems.32 JPay’s tablets appear to be smaller and have less functions than GTL’s, although they both use similar fee-based models to charge for content. When the Indiana DOC held a meeting for interested bidders, eleven companies attended (although it’s not clear how many of those companies ended up submitting proposals).

While some companies (like GTL and JPay) are sizeable, others are smaller startups. One fairly small company provides insight into how investors think there is money to be made by eliminating choices for incarcerated people. American Prison Data Systems is backed by former Citibank CEO Vikram Pandit and several venture capital funds, and proudly brags that its business model is to “[r]eplace physical mail with email and eliminate cost centers such as libraries.” Even more offensive, APDS claims that such actions will lower costs for “prison families.”

Public reaction

It is also unclear how prison staff, incarcerated people, family members, and the general public will respond to new technologies like GTL’s tablets.

Perhaps the most insightful reaction comes from a person who is currently serving time in the Colorado DOC. Quoted in a Westword story about the GTL tablets, the unnamed person remarks:

Most prisoners feel this is fantastic. . . What they don’t see is that the system just issued a $50 babysitter to all of its prisoners. The average prisoner will play games and music 8-10 hours a day, just like any kid in America. Only they aren’t kids; they are men and women who need rehabilitation and education. This buys a lot of safety for prison staff, but what a waste of time for the prisoners. If they provided education, it would be marvelous. Prisoners might just learn something useful and not come back.

Coming from someone with firsthand knowledge of the situation, this description hits all the main points—the tablets serve as a “population management” tool for prison administrators, financially burden incarcerated people, and are a poor substitute for genuine educational opportunities.

The Denver Post article cited a slowly growing acceptance among corrections staff, due to a belief that the program “will reduce friction between rival gangs vying for control of wall phones, occupy inmates who have a lot of time on their hands and eventually allow them to access vocational and educational programming.”

The Post article also contains predictable fearmongering by critics who make broad claims about criminal behavior and use those generalities to argue against any kind of innovation behind bars. One such critic is quoted as saying people in prison “shouldn’t be given something that will give them an opportunity to continue their criminal enterprises in prison.” An apt response to this line of thinking comes from Supreme Court, which just a few weeks ago struck down a North Carolina law that prohibited released sex offenders from accessing virtually any social media website. The Court acknowledged North Carolina’s legitimate interest in preventing crime, but noted that the indiscriminate breadth of the prohibition infringed on the First Amendment rights of people who had served their sentences and were trying to reenter society at large.33 Although the court’s ruling does not directly impact the rights of people who are currently incarcerated, it does illustrate the need for communities to revisit the issue of modern communications in prison, with a realistic and human approach. “While in the past there may have been difficulty in identifying the most important places (in a spatial sense) for the exchange of views,” writes the Court, “today the answer is clear. It is cyberspace — the ‘vast democratic forums of the Internet’ in general, and social media in particular.'”34

Conclusion

Historically, people in prison have communicated with the outside world using tools that were simultaneously specialized and universal. Specialized in the sense that letters and phone calls were subject to restrictions and monitoring for security. Universal in the sense that the actual communications networks were the same ones used by the population at large — namely the nation’s mail system and the network of Bell telephone companies. These networks charged reasonable, regulated rates for universal service.35 Emerging technologies for prison communication are taking a decidedly different approach: instead of applying security protocols to a general purpose network, prisons are relying on specialized providers that use proprietary systems and charge user fees far in excess of cost. The profits of this model are then divided among the prison systems and the private equity firms that own the providers.

New technologies have the potential to help incarcerated people. But the ways in which such systems are being implemented tend to focus on profits over people. The Colorado/GTL contract provides other jurisdictions with a case study in how new technologies can be implemented in ways that financially exploit incarcerated people and their support networks. Other jurisdictions should view the Colorado experience with caution, and strive to develop better, more humane models for bringing prison communications into the twenty-first century.

Illustrations by Elydah Joyce.

Footnotes

- Although the details are not spelled out in the contract, there are some strictly administrative features that are appear to be available without payment, such as filing medical requests, grievances, or submitting commissary orders. ↩

- The original Colorado/GTL contract was signed in July 2015, and called for phone rates of 12¢ per minute. Later that year, the FCC issued new rules capping most calls from people in prison at 11¢ per minute. The current status of the FCC rate caps is subject to some uncertainty given recent court action, see below, note 13. ↩

- Curiously, the Denver Post article quotes a customer from one of the first prisons to implement the tablet program saying that “he paid $6.59 for a two-month subscription to music and games.” This price is not found anywhere in the Colorado/GTL contract, and is likely a “teaser” introductory rate. But it also points to a larger problem: GTL does not publicly post its rates, thereby making it difficult for customers to research and plan a budget. Indeed, for all the public knows, GTL could be charging different prices to different consumers, either based on the prison where a customer resides or based on data profiles of the family members who pay for subscriptions. ↩

- By providing phone service on a tablet, GTL might have an ulterior motive. Other prison telecommunications companies have argued (both in federal court and state regulatory proceedings) that prison phone calls delivered over the internet (Voice over Internet Protocol, or “VoIP”) are not subject to government regulation. This argument may or may not work under certain state laws, but it has so far proven unpersuasive for purposes of federal law — as the Federal Communications Commission acknowledged in 2013, the statute that gives it the power to regulate prison telecommunications is technology neutral and the use of VoIP does not defeat the FCC’s jurisdiction. In the Matter of Rates for Interstate Inmate Calling Services, WC Docket 12-375, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 28 FCC Rcd. 14107 ¶ 14 (2013) (“Section 276 [of the Telecommunications Act] makes no mention of the technology used to provide payphone service and makes no reference to ‘common carrier’ or ‘telecommunications service’ definitions. Thus, the use of VoIP or any other technology for any or all of [a telecommunications] provider’s services does not affect our authority under section 276.”). ↩

- Even though the contract says that DOC will increase the per-call limit, the publicly available phone policy does not seem to have been updated, since it still says calls are limited to 20 minutes. ↩

- While it’s not clear why Colorado’s tablets lack video visitation, Indiana’s request for proposals for tablet service says that that state’s DOC does not want video visitation on the new tablets because, as a security restriction, the devices should not have cameras. Indiana Dept. of Admin., Request for Proposal 17-055 (Mar. 10, 2017), at 5. ↩

- It’s not entirely clear that the music catalog in Pennsylvania is the same as that available to Colorado customers. Instead of a streaming service, Pennsylvania’s tablet program allows music for purchase (at $1.80 per song, plus tax — a price that’s about 40-80% more than a typical song on iTunes). The streaming and download systems could possibly be built on different music catalogs. ↩

- Another source of information about streaming catalog size comes from the bid documents related to the Indiana DOC’s pending solicitation for a tablet system. During the bidding process, one of the unnamed bidders submitted a written question to the state, in which it stated “our music catalog contains almost 11 million songs” (also a much lesser offering than free-world streaming services). GTL wasn’t necessarily the bidder that made this statement, but it was one of the companies considering submitting a bid. ↩

- One surprising but innovative way in which people have combined new and old technologies to maintain communications with incarcerated loved ones is the new use of paper flipbooks sent through the mail. See Noel Black, “Flipbooks help prisoners stay connected to their loves ones,” Nat’l Public Radio, All Things Considered (May 29, 2017). A ban on postal mail, as advocated by the Denver Post, would kill such creative tools in favor of GTL’s pay-to-play messaging platform. ↩

- While there are some security restrictions, these items are all generally allowed under the Colorado DOC’s current mail policy. ↩

- Contract, Exh. B § III(b)(ii). ↩

- One indication of poor contract drafting is the inconsistency in how the value of the “educational content” is measured. The original contract required DOC to assume the “cost of delivering” content once the retail value of that content exceeded $500,000. On the other hand, the amendment does not refer to retail value, but instead uses the phrase “cost in excess of $500,000.” Contract, Exh. B § III(b)(ii) (emphasis added). Not only does this discrepancy make it difficult to figure out how the original deal was supposed to work, but the very concept of retail value of specialized educational content is far from self-explanatory. Because the contract does not contain any guidelines on valuing content, GTL could have manipulated this provision. ↩

- In June 2016, the U.S. Court of Appeals struck down the FCC’s limitation on intrastate phone charges. This means that calls from Colorado prisons to numbers outside of Colorado will still be subject to the FCC rate caps, but calls within the state will not be subject to federal regulation. In many states, intrastate rates are regulated by a state utilities commission; but, in 2003, Colorado legislators prohibited the state Public Utilities Commission from regulating prison telephone service. Colo. Rev. Stat. 40-1-103(1)(b)(VI) (enacted by Senate Bill 03-303). Thus, it appears that GTL will be able to charge whatever rates it wants for in-state calls, subject only to the DOC’s lax oversight. ↩

- The March 2016 contract amendment is illustrative of how prison phone companies make money. The FCC imposed a rate cap of 11¢ per minute and capped ancillary fees. As a result, GTL had to reduce the rates charged to people in the Colorado DOC by 1¢ (from 12¢ per minute to 11¢). A big reduction also came in fees: while the original contract allowed GTL to charge $7.95 for friends and family to deposit money into a prepaid account, in addition to charging $3.95 when someone wanted to close an account. The FCC order capped payment fees at $3 for automated payments (or $5.95 for payments using a live operator) and prohibited account closure fees. As noted above (footnote 13), the FCC’s rules have been struck down as they apply to intrastate calls, thus creating a two-track regulatory regime depending on whether a call crosses state lines. ↩

- Colo. Rev. Stat. 17-32-102. ↩

- GTL’s promotional materials brag that its tablets have been tested and designed to withstand dropping or other blunt force. Interestingly, the testing procedure used by GTL is part of a comprehensive array of quality tests developed by the military, but GTL apparently chose to use only use one of the many tests outlined in the military procedures. In any event, GTL doesn’t mention the quality of the hardware manufacturing process (which could lead to failure for reasons other than blunt force) or the software that runs on the tablets. ↩

- Contract, Exh. B § III(a)(i)(3) (emphasis added). ↩

- Indiana Dept. of Admin., RFP 17-055, Q&A Response #2 (Mar. 8, 2017), answer to question 28. Similar to the Colorado DOC tablet program, Indiana has stated that hardware should be provided free of charge, but vendors can recoup costs through fees for electronic content. See Indiana Dept. of Admin., Request for Proposal 17-055 (Mar. 10, 2017), at 6. ↩

- The exact contractual language reads as follows: “[GTL] shall replace or repair on a one-time basis per inmate any tablet that is damaged or destroyed for reasons other than a willful act [subject to the limitations described below, in note 20].” Contract, Exh. B § III(a)(i)(4). So what happens in the case of someone who is serving a ten-year prison sentence? Is he or she supposed to hope that their tablet will only malfunction once over the course of ten years? ↩

- Contract, Exh. B § III(a)(i)(4)(a) (“[GTL] shall have no obligation during any twelve (12) month period to replace or repair in any housing unit within a Location more than five (5) Tablets or a number of tablets equal to five (5%) percent of the Tablets deployed at that housing unit, whichever is greater.”) ↩

- Contract, Exh. B § III(a)(i)(4)(b) (“[GTL] may cease providing the Mobility Service at any housing unit within a Location, and remove the Tablets deployed to that Location, if [GTL] has repaired and/or replaced in any twelve (12) month period ten (10) Tablets or a number of Tablets equal to ten (10) percent of the Tablets deployed at that housing unit, whichever is greater.”). ↩

- This report defines “failure” as “excessive performance issues that could not be resolved.” Thus while a device may “fail” and still be usable, clearly the customer will not be able to use a failed device to its full potential. ↩

- Contract § 7(A). ↩

- Colo. Rev. Stat. 17-42-103 (enacted by Senate Bill 15-195). ↩

- In fact, there doesn’t appear to be any public materials on GTL’s website that clearly spells out the patchwork of refund rules. One of the only places where this dichotomy is directly addressed is in the actual contract between Colorado DOC and GTL, which end users are hardly likely to have access to. Even the contractual language is a confusing jumble: “Once purchased, Link Units may only be returned to an inmate’s trust account or otherwise redeemed by the inmate (as applicable) upon termination of the [tablet program] at all Locations or upon an inmate’s release. All Link Units purchases [sic] by inmate friends or family are final.” Contract, Exh. B § III(b)(iii). ↩

- Contract, Exh. B § III(a)(i)(1). ↩

- Terms of Use § R(2). ↩

- Terms of Use § Q. What makes this provision so objectionable is that a customer is forced to indemnify GTL against any claims “arising from or related to” the customer’s use of the company’s products. It’s common for such clauses to cover claims related to a customer’s misuse of a service, but GTL’s contract could lead to absurd results. For example: suppose someone signs up for a GTL account and transfers funds to someone in prison. Suppose further that GTL makes an error and the transfer isn’t completed; the customer then files a complaint with their state consumer protection agency. If GTL incurs costs (such as attorney fees) when responding to an agency inquiry, this indemnification clause theoretically puts the customer on the hook for those costs. ↩

- Privacy Policy § E(4). ↩

- Contract § 29(G). ↩

- GTL’s Terms of Use does allow customers a limited ability to opt out of arbitration. This is a defensive mechanism that some companies use to insulate their contracts from legal challenges. There is not much reason to think that opt-out provisions really help consumers, plus GTL reserves the right to cancel the service of any customer who actually exercises their “right” to opt-out. ↩

- As noted above, JPay is now a subsidiary of Securus Technologies. Yet Securus advertises its own tablet, which it claims is available “at various locations across the United States.” It is unclear whether Securus will consolidate its tablet product with that offered by JPay, or if the company will continue to operate dueling programs. ↩

- Packingham v. North Carolina, Case No. 15-1194 (U.S. Sup. Ct. Jun. 19, 2017), slip op. at 6-7 (“For centuries now, inventions heralded as advances in human progress have been exploited by the criminal mind. New technologies, all too soon, can become instruments used to commit serious crimes. The railroad is one example, and the telephone another. So it will be with the Internet and social media …. The government, of course, need not simply stand by and allow these evils to occur. But the assertion of a valid governmental interest cannot, in every context, be insulated from all constitutional protections.” (citations omitted)). ↩

- Id. at 4-5 (quoting Reno v. Am. Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844, 868 (1997) (citation omitted)). ↩

- It is true that prison phone calls have long been expensive because calls often had to be placed as operator-assisted collect calls. Even though those the rates for collect calls were more expensive than a typical payphone call, before the deregulatory environment of the 1990s, in-prison collect calls were charged the same rates that applied to all collect calls — rates which were set by regulators who ensured that phone charges covered costs and provided the operator with a reasonable rate of return. See generally, Stephen Raher “Phoning Home: Prison Telecommunications in a Deregulatory Era,” in Prison Privatization: The Many Facets of a Controversial Industry (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2012), 2: 215-249. ↩

To get an impression of the service quality of GTL, you only needed to read the postings, comments and ratings from users on GTL Connect’s Facebook page. These postings and ratings have vanished since, GTL doesn’t seem to like bad publicity…

The email service in PA is a mess. Although messages cost 25cts “only”, you only get 2000 characters (not words! spaces count as characters!) for that price. And messages take between a few hours and more than a week to arrive (in both ways), and rarely arrive in chronological order. So you never know how long it will take for a message to be received.

It also happens frequently that you are thrown out of your account for no apparent reason, while in the midst of writing a message. This message is then lost of course and you can restart to write your message. Sometimes you can’t access your account at all.

One more comment to the song download option in PA’s prisons. Not only is the cost of these songs much too high, prisoners have also seen their paid-for and downloaded songs erased by the DOC, because they were not “approved”. And they didn’t get any refund for the removed songs. Why do they offer songs that are not approved in the first place? Of course, these songs are not labelled as “not approved” and therefore you download everything at your own risk. This is appalling.

Are the differences in service/product prices for offenders as compared to beyond bars similar services/products due to the fact that the tablet is free to the offender and that investment has to be recouped? On the outside, these products/services assume you own the hardware to run them on.

What about security. How are these services being monitored when used by the offenders and who is paying for that? Is that component also something that has to be paid for indirectly by the offender when they buy the products and services? On the outside, security is not an issue and so it does not have to be paid for.

I do not know the answers, but just wanted to ask the questions.

As a freshly released Pennsylvania prisoner let me give you my (and many other prisoners) perspective on GTL – THEY ARE EVIL. They make sooo much money off families of the incarcerated that they should be in prison. I purchased a tablet that didn’t work from the first day and sent it back seven times over the course of a year. They never fixed the problem and when I complained they simply told me to buy another one. At $ 150.00 a pop this is big money when the average prison job pays something around 22 cents an hour. To listen to music you have to buy songs at twice the going rate and then they screw you over by taking the song off the tablet and saying the prison didn’t approve it. What? I absolutely despise these people and will bad mouth them every chance I get