This report has been updated with a new version for 2023.

You’ve Got Mail:

The promise of cyber communication in prisons and the need for regulation

a Prison Policy Initiative report

by Stephen Raher

January 21, 2016

- Table of Contents

- Options behind bars

- Overview of the industry

- Overview of messaging services

- Recommendations

- Footnotes

- Exhibits

Executive Summary

I. Communication Options Behind Bars

As with most aspects of life, communications options for incarcerated people are in flux due to technological changes. For practical, political, and technical reasons, communications methods have evolved more slowly in prison than in the outside world, but change is nonetheless here. New technologies such as video visitation and electronic messaging have the potential to improve quality of life for incarcerated people and help correctional administrators effectively run secure facilities. Yet the promise of these new services is often tempered by a relentless focus on turning incarcerated people and their families into revenue streams for both private and public coffers.

The lucrative market for prison-based telephone service has received substantial attention since 2012, when the Federal Communications Commission reinvigorated a long-stagnant regulatory proceeding concerning rates and business practices in the ICS market.1 Although the focus of the FCC proceeding has thus far been on telephone service, ICS is not just limited to voice calls — there are emerging technologies with which a growing number of prisons and jails are experimenting.

At the outset, a word about terminology is necessary. News coverage of electronic messaging in correctional facilities often refers to the service as “email for prisons.” Although using the term “email” is a convenient shorthand, it is not accurate. Electronic messaging services allow free-world users to send (and sometimes receive) written communication electronically, but that’s about the end of the similarities between traditional email and prison-based services. Some differences are obviously related to security — e.g., messages often must be reviewed before they are delivered to the recipient, attachments are limited or prohibited, and sometimes new users must be approved before they can communicate with an incarcerated user. There are also important technical differences that impact the growth and use of this new technology: traditional email is based on a standardized architecture that promotes interoperability and competition among providers, whereas electronic messaging uses proprietary stand-alone systems.2 Some important differences are as follows:

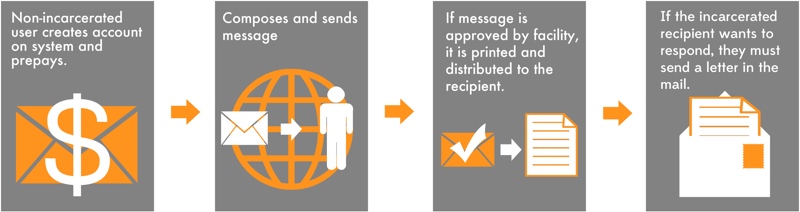

- One-way systems: some providers offer jails the ability to select “inbound only” service. In these systems, after a free-world user sends an electronic message, the message is reviewed by facility staff and then printed and distributed to the recipient on paper. If the recipient wants to respond, he or she must send a written letter through the mail.

- Price: people are used to email being free. Even if you pay for email as part of a bundle of services from an internet service provider, there is no incremental cost for each email you sent or receive. With prison-based electronic messaging services, there is almost always a fee. Often the cost is paid by free-world users, sometimes it is paid by incarcerated users. Typically users pay a flat fee per message.3

- Method of access: people are used to accessing email in a variety of manners — on their phone, through software installed on a computer (e.g., Microsoft Outlook), or through a website. Most electronic messaging services require users to write, send, receive, and read messages using special proprietary software. For non-incarcerated users, this means going to a website, logging in, and typing your message.4 Some systems might send you a regular email letting you know you’ve received a new message, but to read it you will need to log in to the provider’s website.

- Character limits: electronic message providers often limit message length, with every letter, period, and space counting against the limit. Limits can be as high as 6,000 characters and as low as 1,500 characters. Want to send someone a copy of Matthew 25:31-46 (the Bible parable that famously proclaims “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink … I was in prison and you visited me.”)? That passage is 1,916 characters, and would need to be split into two messages. Want to send Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”? That would take twenty-seven separate messages under a 1,500-character limit. This report? Fifty-nine messages.

- Data retention: almost all modern email systems have extremely generous (sometimes even unlimited) data storage capacities for users. Electronic messaging systems do not allow free-world users to easily download messages, and storage is subject to capricious (and usually unwritten) data retention policies imposed by the company. Written communication can be a valuable way of preserving thoughts, facts, and ideas that can later serve as evidence in litigation, answer questions, or bring back memories of deceased friends. Users of prison-based systems have no reliable way to preserve messages short of printing copies one at a time. At the same time, even if users cannot access older data, facilities can usually access messages for years or decades after the fact, for use by law enforcement.

A. Traditional Communications Channels

Emerging technologies are attractive to both end-users (i.e., incarcerated people and their families) and correctional administrators for a variety of reasons, including certain advantages that new methods enjoy over traditional channels. To better understand the context of electronic messaging, here is a summary of the three traditional communications channels in prisons and jails: in-person visiting, phone calls, and postal communication.

In-person visiting

Research has consistently shown that in-person visits help reduce recidivism rates among people who are released from prison. Despite these positive results, visitation is hampered by burdensome facility regulations and the unfortunate fact that vast numbers of people are incarcerated far from their home communities.5

Although in-person visits remain an ideal method through which incarcerated people can maintain ties with their family and support network, policy makers should support other technologies (including electronic messaging) that can supplement personal visits when time, expense, and distance are obstacles.

Phone calls

Phone calls offer a lifeline to people in prison and jail: a chance to talk in real time with someone on the outside, regardless of how many miles separate the two callers. Because it remains the major form of communication between incarcerated people and their loved ones, and because correctional facilities grant monopoly contracts to telecommunication providers, the prison phone industry has become a hotbed of exorbitant pricing and questionable business practices.6 The FCC has found that competition among ICS providers does not benefit consumers, and therefore the Commission has declined to rely on market forces to ensure just and reasonable rates.7 In its First Report and Order, the FCC established preliminary rate caps on interstate calls.8 The Commission’s Second Report and Order imposed a tiered rate-cap system on all calls (inter- and intrastate) as well as restrictions on ancillary fees.9 As a result of the FCC’s actions, rates for prepaid phone calls are currently capped at $0.11-$0.22 per minute.10

A major focus of the FCC’s rulemaking has been the prevalence of “site commissions” (or kickbacks), wherein a prison or jail receives a percentage of phone revenues as an incentive for granting a monopoly contract. The FCC, recognizing the perverse role that site commissions had in driving prices up, has now prohibited ICS providers from accounting for site commissions as expenses (which is a significant, if somewhat arcane, step in terms of regulatory law).11 At the same time the FCC’s actions have helped make phone service more accessible to incarcerated people, ICS providers have lost their leading source of inflated profits. As a result, the leading companies have been quick to expand into areas where price regulation is still in flux. Even though the FCC has explicitly asked for comment on whether it should regulate emerging technologies,12 providers have rushed to stake claims in this market where exorbitant pricing is currently unfettered by consumer protection oversight.

Postal communication

For centuries, written correspondence transmitted through the mail has been an important means of communication for incarcerated people.13 Mail remains important because it provides a universal delivery network to people both in and outside of prison, with minimal technological barriers.

Mail still serves as a versatile and accessible communication tool for people in prison and jail, but it is not as speedy as it used to be. Due to complex political and economic factors, the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) no longer serves the role it used to occupy as a low-cost provider of quick delivery service. Letters to and from prisons are typically sent by first-class mail. Due to service cutbacks at USPS, delivery time for first-class mail has dramatically lengthened in recent years,14 making the mail increasingly impractical for time-sensitive communications. Postal mail is also under attack in some facilities. Some jail administrators, seeking to cut mailroom costs or claiming security concerns, have attempted to restrict mail by requiring that all incoming mail be on postcards.15 Not only are postcard-only policies contrary to correctional best practices, but the policies are usually struck down as unconstitutional when challenged in court.16 Although the potential for earning fee revenue from electronic messaging services does not yet appear to have spurred widespread adoption of postcard-only policies, at least some counties have sought to introduce electronic messaging in conjunction with restricting letter mail.17

B. Electronic Messaging

Electronic messaging typically operates on a closed network that does not directly interact with normal internet-based email systems.18 The specific way that the service works varies among providers and facilities. Most systems19 fall into one of two dominant models:

- Inbound-only systems. These systems only allow one-way electronic communication, coming into the facility. The non-incarcerated user accesses the system through the provider’s webpage. The user types and pays for the message, which is then sent electronically to the jail. After it is approved for delivery (which is sometimes automated and other times requires manual staff review), the message is printed out and delivered to the recipient. If the incarcerated user wants to respond, he must do so by postal mail.

Figure 1. Inbound-only systems. For some electronic messaging systems, the non-incarcerated user sends a message into the correctional facility electronically, but the incarcerated user must respond by postal mail.

Figure 1. Inbound-only systems. For some electronic messaging systems, the non-incarcerated user sends a message into the correctional facility electronically, but the incarcerated user must respond by postal mail.

- Two-way systems. Non-incarcerated users access these systems the same way, but the message is not printed for delivery. Instead, incarcerated users access the system through shared “kiosks” or other devices controlled by the correctional facility. But both parties can only compose, send, and read messages using the provider’s software and network (some systems require all communications to be initiated by the non-incarcerated user). For free-world users, this means having to use the provider’s system instead of a normal email account.

Figure 2. For two-way electronic messaging systems, both the non-incarcerated and incarcerated users send and receive messages electronically. Note that even the non-incarcerated users must use the provider’s system, not a normal email account.

Figure 2. For two-way electronic messaging systems, both the non-incarcerated and incarcerated users send and receive messages electronically. Note that even the non-incarcerated users must use the provider’s system, not a normal email account.

Electronic messaging is one of several emerging technologies gradually appearing in prisons and jails, sometimes on a trial basis. Video visitation is another such technology, currently used in over five hundred correctional facilities in the U.S.20 In addition, some facilities allow limited-function tablets that can access closed messaging systems and other apps.21 Patent applications have even been filed for security-monitored closed “social networks” for use in prisons.22

One major issue in the field of emerging technologies is the extent to which incarcerated users can access the internet. This does not directly impact electronic messaging, because messaging services operate on proprietary platforms that do not allow incarcerated users direct access to the internet. Nonetheless, internet access in correctional facilities is becoming an increasingly salient issue, as more core functions of government and commerce shift to online-only platforms. It is reported that “[m]ost, if not all, states ban prisoners from direct, unsupervised access to the Internet;”23 however, it is likely that most of these bans are administrative decisions made by prison administrators. A handful of states have gone further and enacted statutes prohibiting or restricting people in prison from having internet access.24

II. An Overview of the Industry

A. Meet the Contestants

Correctional facilities that offer electronic messaging do so through private for-profit contractors. Prison Policy Initiative identified twelve companies25 that offer such service within the U.S. (see table 1). These companies generally fall into four different categories, as discussed below. With one exception, it appears that providers do not focus exclusively on electronic messaging. Rather, the companies tend to operate a variety of services that collect user fees and are made available to correctional facilities at little to no cost. Electronic messaging is usually offered to facilities as an optional add-on feature, bundled with other services.

| Company | Product Name | Primary Business Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Technologies Group, LLC | CorrLinks | General correctional technology |

| Global Tel*Link Corporation | Message Link | General ICS |

| Inmate Calling Solutions, LLC d/b/a/ ICSolutions (subsidiary of Centric Group) | Access Corrections, SecureMail, SecurePhoto | Financial companion to commissary operations run by Keefe Group |

| JPay Inc. (acquired by Securus) | no specific name | Financial transactions |

| Prevatek Development LLC (subsidiary of Trinity Services Group, Inc.) | Smart Deposit Plus | Financial transactions |

| Renovo (acquired by Global Tel*Link, June 2014) | VisMail | Video visitation |

| Securus Technologies, Inc. | Secure Instant Mail | General ICS |

| Smart Communications US, Inc. | SmartJailMail | Electronic messaging only |

| T.W. Vending Inc. d/b/a TurnKey Corrections | InmateCanteen.com | Commissary; video visitation |

| Tech Friends Inc. | JailATM | Financial transactions |

| Telmate, LLC | GettingOut | General ICS |

| VendEngine Dev. | Inmate Email | Financial transactions |

General ICS providers

Three general ICS providers offer electronic messaging as an option bundled with other communications services such as voice telephone and video visitation. These companies — Global Tel*Link, Securus, and Telmate — have all been active in the ICS rulemaking proceeding, and all are currently suing to strike down the FCC’s new prison phone rules.26 A fourth company, Renovo (offering electronic messaging under the “VisMail” brand), was acquired by Global Tel*Link in June 2014.27

It is not clear whether electronic messaging is currently a substantial source of profits for traditional ICS providers, but offering such service is likely part of a strategy of diversifying corporate revenue sources at the expense of incarcerated people and their families. At the moment, voice telephony is no longer the lucrative business enterprise it has been in the past, and if the ICS providers are unsuccessful in their litigation against the FCC, sky-high profits for phone service are unlikely to return. It is thus in the providers’ financial interest to expand into unregulated business lines, restoring their ability to charge supracompetitive rates to customers who are not able to chose providers. Indeed, this shift in revenue focus is expressly part of Securus’s business model — when seeking financing to fund its acquisition of JPay, Securus boasted to lenders that it expected 65% of its 2015 revenue to be from businesses that are not subject to rate-of-return regulation (down from 100% in 2007).28 This new focus on unregulated activities brings up the distinct likelihood that ICS providers are using common facilities to provide both regulated and unregulated services, with certain activities cross-subsidizing others.29

Commissary operators

Two electronic messaging providers are associated with contract operators of jail commissaries. TW Vending, Inc. (doing business as TurnKey Corrections) operates jail commissaries, which are increasingly dependent on computerized ordering systems. These systems typically involve public computer “kiosks” deployed in jail living units, and TurnKey allows jails to offer electronic messaging on these kiosks. Similarly, Inmate Calling Solutions, LLC (doing business as ICSolutions) is a subsidiary of Centric Group, LLC, which is the parent of Keefe Commissary, a large national for-profit commissary operator.30

Financial services firms

A growing number of companies have arisen in the carceral economy to provide financial services such as money transfers, issuance of prepaid debit cards upon a person’s release from confinement,31 or collection of payments for bail, fines, and fees. The hardware and software that is already in place for these transactions allows operators to add electronic messaging services as an add-on feature. Four financial services companies currently offer electronic messaging: JPay, Prevatek Development LLC (doing business as Smart Deposit Plus), Tech Friends, Inc. (doing business as Jail ATM), and VendEnging Dev. In April 2015, Securus announced its acquisition of JPay.32 Securus has also formed a joint venture with Tech Friends to provide services at the Knox County, Tennessee, jail,33 thus raising the question of whether Tech Friends is a potential acquisition target for Securus.

Specialty companies

Prison Policy Initiative identified two companies that do not fit within any of the previously mentioned categories. First, Smart Communications US, Inc. is based in Florida and offers service under the brand SmartJailMail.com in roughly a dozen jails, primarily in the southern U.S. It appears to be the only company that focuses exclusively on electronic messaging.

Second, Advanced Technologies Group, LLC (ATG) sells different types of software to a variety of correctional agencies and other law enforcement entities. ATG offers electronic messaging in federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) facilities and in the Iowa and Oklahoma state prison systems.34 The electronic messaging program offered by the BOP is somewhat unique in that it does not charge free-world users to send or receive messages,35 but incarcerated users do pay.36

B. Procurement Practices

Much has been written about the procurement models for phone service in prisons and jails: the facility selects a provider and signs a contract (typically multi-year) granting the provider a monopoly on phone service in the facility. Often, in return for receiving the contract, the provider agrees to pay the correctional facility in the form of a kickback (“site commission”) based on phone-call revenue. This same model is generally used for electronic messaging, although as noted above, messaging tends to be bundled with other services.

Correctional facilities hardly ever pay to implement electronic messaging.37 Most facilities make money through commissions, although not all contracts contain commission provisions. In at least one case, a jail receives an annual gift of $100,000 from Telmate, on top of a 69% phone commission (under a contract for phone, video, and electronic messaging).38 Details about commissions are discussed in greater detail in the following section.

Although electronic messaging service is usually governed by a direct contract between the provider and the correctional facility, there is one notable exception. Tech Friends, Inc. (Jail ATM) frequently appears to provide electronic messaging as a subcontractor. Of the six jurisdictions that offer Tech Friends service and which responded to Prison Policy Initiative’s public records requests, four produced contracts with different third-party vendors who operate jail commissaries. The commissary operators then apparently subcontract with Tech Friends to offer electronic messaging on jail computer kiosks.39 One county provided a contract with Tech Friends that specifically addressed electronic messaging services. Another county produced a contract with Tech Friends that contained no mention of electronic messaging, even though the facility appears to offer the service.40

Subcontracting structures raise serious concerns about accountability and transparency. For example, contracts for electronic messaging typically provide clarification on ownership of content and user privacy. Even though these terms are often problematic (see section III.C below), at least there isn’t a dispute over what the governing agreement is. In the case of a subcontractor, it can be difficult to even determine whether there is an enforceable contract, and if so, what the terms are.

C. Revenue and Fee Structures

Because electronic messaging is so frequently offered as one part of a bundle of services, it is hard to tell how lucrative this service is for facilities or providers, or what role it plays in contract negotiations. Although there is scant public information on the profitability of electronic messaging for providers, it has been lucrative for at least one company. In 2014, JPay had electronic messaging contracts with seventeen prison systems, covering 500,000 incarcerated users. That year, JPay’s electronic messaging income was $8.5 million (12% of total corporate revenue).41

With extremely limited exceptions,42 providers make money by charging fees to end-users.43 It is difficult to directly compare prices between providers because message bundles, volume discounts, ancillary fees, and character limits make dollar-to-dollar comparisons unreliable.

User fees are typically set in a contract between the correctional facility and the provider, meaning that the same provider often charges different fees at different facilities that it serves. At the majority of facilities, fees tend to be in the neighborhood of 50¢ per message, however Prison Policy Initiative discovered fees for text-only messages ranging from a low of 5¢ per message44 to a high of $1.25.45 Some systems offer the ability to send pictures or other attachments for a separate (usually higher) fee.

Ancillary fees can also increase out-of-pocket costs for users. For example, InmateCanteen.com (operated by Turnkey Corrections) requires advance deposits, which are subject to a flat $8.95 “convenience fee.”46 After a user makes a deposit, her available balance is subject to a $1 per-month “maintenance fee.”47 Securus charges a $1.95 fee for a deposit of $5 (with larger deposits subject to higher fees).48 Worse still, these fees are only disclosed at the time of purchase. Because the fees are not mentioned in the facility contracts or in the providers’ publicly available terms and conditions, facilities are unable to take into account the full cost to incarcerated people and their families when choosing a provider.

The wide range of fees suggests that prices are not based on provider costs, which is not surprising given the fact that electronic messaging services typically take advantage of hardware that is already installed for other purposes (i.e., commissary ordering or video visitation) and the costs to operate a closed electronic messaging network are likely quite low.49 To the extent that rates are simply profit-taking, this pricing would seem to contradict the spirit of the American Correctional Association policy regarding phone rates, which specifies that rates and surcharges should be commensurate with free-world prices, and any deviations should “reflect actual costs associated with the provision of services in a correctional setting.”50

Indeed, the fact that so many facilities offer electronic messaging at 50¢ per message suggests that prices are likely set with an eye toward the cost of the most similar competing product: a single-piece first-class letter. In fact, JPay expressly admits to setting rates in relation to postage prices,51 and refers to prepaid message credits as “stamps.”52 This linked-pricing effect is not economically efficient, because letter postage rates are legally required to cover the Postal Service’s direct and indirect costs of delivering first-class mail,53 something that has absolutely no relevance to the cost of providing electronic messaging service in correctional facilities. With prices that bear little relation to cost, and customer choice vested in correctional procurement officials who are not charged with protecting the rights of end-users, electronic messaging appears to suffer from many of the same perverse pricing dynamics that spurred the FCC to regulate phone rates in prisons and jails.54

Finally, some facilities sign contracts that do not protect against arbitrary future price increases. Although many contracts require advance approval of the facility before the provider can raise rates, some contracts specify that such approval shall not be “unreasonably withheld,”55 and others do not require facility approval at all. When providers can raise rates at will (or when a contract establishes a presumption that facilities will rubber-stamp rate increases), then facilities run the risk that they will be locked into a long-term contract with no control over rates.

Kickbacks

Some jails and prisons make money by receiving commissions from electronic messaging revenue. Commission rates can be set as an amount per message (from 5¢ to 20¢),56 or a percentage of revenue derived from the contract (from 10% to 50%).57

It is difficult to tell whether commission revenues are substantial, but limited information suggests that electronic messaging income is minimal. For example, when Praeses LLC58 examined total revenues and commissions under a contract between JPay and the Kansas Department of Corrections, it reported that for the sixteen months ending February 2015, the DOC received average message transmission revenue of $1,674 per month, in addition to $92 per month from fees for printing messages.59 This results in average monthly per capita revenue of only 18¢ per person incarcerated in the Kansas prison system. When Santa Barbara County, California, added electronic messaging to its contract with Keefe Commissary Network, the county estimated that kickback revenue would average $500 per month.60 It is important to note, however, that many electronic messaging contracts involve smaller jurisdictions with smaller jail populations, in which case commission revenue is likely de minimus.

| Smallest Available Bundle | Largest Available Bundle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility | Vendor | Single Message Price | Message Quantity | Cost for Bundle | Per-Message Cost | Message Quantity | Cost for Bundle | Per-Message Cost |

| Williamson County, TX | ICSolutions | $0.60 | 5 messages | $2.75 | $0.55 | 40 messages | $18.00 | $0.45 |

| Champaign County, IL | ICSolutions | $0.40 | 5 messages | $1.75 | $0.35 | 40 messages | $9.99 | $0.25 |

| Pennsylvania DOC | JPay | n/a (bundled only) | 5 messages | $2.00 | $0.40 | 50 messages | $10/month recurring | $0.20 |

| Colorado DOC | JPay | n/a (bundled only) | 5 messages | $2.50 | $0.50 | 45 messages | $18.50 | $0.41 |

End-user Pricing

Cost per message is not the only relevant metric when evaluating the reasonableness of rates. Many providers further complicate customer pricing by using volume discounts, prepayment requirements, or recurring payments.

At least two companies (ICSolutions and JPay) charge differently depending on how many messages a customer pre-purchases. ICSolutions offers a single-message price, and then discounts for pre-purchases of multiple messages, up to forty. JPay, in some of its contracts, requires customers to pre-purchase at least five messages. Tech Friends (JailATM) and Smart Communications (SmartJailMail.com) both require users to prepay (at least $5 at a time), but do not use volume discounts.

The primary problem with incentivizing or requiring customers to prepay for electronic messaging service is that fees are nearly always non-refundable. In the case of a jail, where a person’s period of incarceration can be brief, it is likely that many family members sign up for the service to communicate with a particular relative in jail. When that relative is released, there will probably be unused funds in the account. Given the churn of people through county jails (11 million people annually),61 it seems that messaging providers count on customers forfeiting unused funds as part of their business model, a tactic that has been used by phone providers as well.62

III. Overview of Messaging Services: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Electronic messaging in correctional settings has the potential to be a beneficial tool, and if implemented correctly could provide value to everyone involved. But there are enough drawbacks — some inherent in the technology and others resulting from business practices — that electronic messaging should not be thought of as a replacement for regular mail. In addition, the technology is unproven enough that the potential exists for other, unforeseen problems as usage expands.

A. Benefits of Electronic Messaging

Similar to the potential benefits of phone calls, electronic messaging allows comparatively timely communication between incarcerated people and their friends and families. In fact, in some situations electronic messaging can be more convenient than the telephone (for example: providing quick notification of a sudden emergency, or scheduling a time for a visit or phone call).

Correctional facilities also stand to benefit from electronic messaging. Electronic communications reduce work in facility mailrooms by avoiding the need to manually inspect mail. Providers aggressively emphasize these cost savings when seeking new contracts. For example, TW Vending markets its service by promising that it’s “a great source of revenue for facilities; All while saving time, money and resources.”63 Smart Communications boasts that it helps “eliminate the nightmare” of the “overwhelming influx of postal mail received by correctional facilities”64 and claims that it has submitted a patent application for a “postal mail elimination system.”65 Despite the promises made in sales pitches, it does not appear that anyone has measured budgetary savings or other efficiencies resulting from electronic messaging.

There are also security benefits. Staff reviews of message contents can be done electronically, and investigators can monitor messages using customized queries. While such security features can undoubtedly help investigators, some companies cynically play on negative stereotypes, for example, by promising that “[t]he more an inmate communicates, the more likely he or she will self incriminate.”66

Messaging also helps avoid the introduction of contraband through the mail. Again, while this is clearly a benefit, it can be difficult to differentiate between actual results and overblown promises in marketing materials.67 If electronic messaging is as efficient as its supporters claim, then it would make sense for facilities to pay the costs of the system out of their operating budgets, without extracting fee revenue from families who already pay a financial toll when a loved one is incarcerated.68

B. Drawbacks

Electronic messaging is not a substitute for postal mail. Despite the potential benefits of electronic messaging, it is not an adequate replacement for traditional mail. Indeed, a number of “inbound only” electronic messaging systems are technically incapable of supplanting mail because they do not allow the incarcerated user to initiate or reply to messages; thus, any outgoing communication must still be on paper. But even the two-way systems lack many benefits found in postal communication. Consider the following:

- Accessibility for free-world users. Not everyone has or is comfortable using a computer. Internet access is least available in poor households and among African-Americans and Latinos69 — populations that are overrepresented in prisons and jails.

- Ease of use for incarcerated users. The way in which users access messaging systems inside correctional facilities is often not conducive to thoughtful and meaningful communication. Prisons and jails are generally “rough” environments, but when writing a paper letter, someone can choose a quiet time and a comparatively private location to think and write. Except in the few experimental tablet-based systems, messaging systems usually utilize shared computer “kiosks,” which are often in public recreational areas. These kiosks afford little privacy and are presumably the subject of demand by multiple users at any given time.

- Right of access. There is a long and detailed line of court opinions concerning the right of incarcerated people to send and receive mail.70 Electronic messaging systems are new enough that case law has not addressed right-of-access issues. Prison systems typically insist that electronic messaging is a privilege, not a right. As long as that is the prevailing attitude, then facilities that use messaging must ensure equal or better access to postal mail.71

- Enclosures and attachments. Postal mail easily allows people to send pictures, newspaper clippings, or other printed items to friends or relatives inside. Electronic messaging services often prohibit attachments, or allow them with restrictions and at additional cost.

- Security. Although it may be counter-intuitive, in some important ways, postal mail is more secure. Of course, most incoming mail is subject to inspection by prison staff. But before an incoming letter reaches the prison (or after an outgoing letter leaves), the privacy of the sealed letter while it is in transit is strongly protected by federal law.72 In contrast, when someone sends or receives messages through an electronic service, the contents are held (even after its “delivery”) by the service provider. Providers are vulnerable to data breaches. In November 2015, Securus suffered an enormous breach of nearly 70 million phone-call records, which included the release of some call recordings.73 In an age where large corporations and government agencies fall victim to unauthorized data access on a regular basis, it is obvious that electronic messaging providers are vulnerable as well. Not only could unauthorized access to messaging data cause serious problems for users, but providers often seek to prevent users from suing for their damages.74

Character limits

Most providers impose a character limit, which can range from 1,500 to 6,000 characters, including spaces. These limits can make communication difficult (see above, section I) and can — to the extent that users have to break up longer communications into multiple messages — potentially increase user costs. As with ancillary fees, character limits are not always disclosed in the contracts that facilities sign, so it’s not clear whether facility administrators have the full picture when selecting providers.

Diffusion of accountability

One often underappreciated benefit of postal communication is that the Postal Service is under a legal obligation to provide universal service.75 In sharp contrast, electronic messaging providers frequently write into their terms of service that they can terminate service for any reason. Most providers also prohibit children (the minimum age for users is usually set at eighteen or thirteen76) from using the service, which presumably means that if a twelve-year-old writes a message to her incarcerated father, she (and her non-incarcerated parent who created the account) are violating the terms of service. This is deeply ironic given that industry markets itself as serving families.

C. Unknowns

Because electronic messaging is such a recent development, there are some issues that are not entirely clear. Whether or not these potential problems develop, it seems that many correctional administrators do not give extensive thought to issues like data breaches and ownership of intellectual property.

Protection of data

As recent high-profile data breaches have illustrated, protection of electronic information is extremely important. Electronic messaging providers hold two types of sensitive data: personal information (like names, addresses, and payment card information) and content (the actual messages exchanged between users). This information is subject to a mixture of laws and contracts, some of which are poorly written. Although the vulnerability of users’ data depends on many variables, some themes are apparent.

The logical starting place in discussing data protection is the providers’ privacy policies. In the tech world, privacy policies usually cover personal information, but sometimes poor drafting leads the reader to wonder whether content is included as well. Messaging providers’ policies can be shockingly unfair to users. For example, Global Tel*Link collects a variety of information about users (including which other webpages a user visits before or after using GTL’s messaging service) and states that it can use such data for “any business or marketing purpose.”77 Other times, privacy protections can be difficult to even understand. Securus’s privacy policy actually seems decent, because it states that Securus will not sell, trade, or transfer personal information (although this protection can be modified or eliminated at any time without prior notice).78 However, a separate user agreement requires all Securus users to agree that they have no expectation of privacy and correctional facilities can distribute, transfer, or even sell content and related information to other parties.79 Other providers’ policies are plainly inadequate — Smart Communications’ policy is two sentences long and merely says that the company will not disclose payment card information.80

One reason why data protection is so important is that providers often retain user data for long periods of time. This is also another significant difference between electronic messages and postal mail — although both are subject to inspection by the correctional facility, copies of regular letters are rarely retained. The rationale for long data-retention periods is that messages may be needed for criminal investigations. Examples of data retention provisions include:

- JPay: Data retention can vary by jurisdiction. One of the most detailed provisions is found in the contract with the Colorado Department of Corrections. The JPay/Colorado agreement requires JPay, upon termination of the contract, to transfer all data to the replacement provider or the DOC.81 Colorado’s contract is unique in that it provides very specific protections for user data: JPay is prohibited from using data for anything other than providing services under the contract.82 As good as this provision seems at first glance, the contract also specifically states that its protections cannot be enforced by users,83 so if the DOC declines to enforce this clause, users may be left with no remedy at all.

- Securus: “Records, data, and information” that is “related to” Secure Instant Messaging service (this language seems to include message contents) is the “sole and exclusive” property of Securus.84 Securus agrees to let the contracting jurisdiction access data during the term of the contract, after which it reverts to Securus’s sole control. Interestingly, Securus allows correctional facilities to access statistical information about system usage, but prohibits the facility from disclosing this information to anyone else.85

- Smart Communications: Messages are kept for seven years from the date of creation.86

- TurnKey: Messages are retained for the life of the contract, plus six additional years. Messages are property of the contracting jurisdiction, and cannot be disclosed without the jurisdiction’s authorization.87

Although the intended purpose of record retention is to aid in investigations, that does not mean that data cannot be used for other purposes. It’s not hard to imagine messages being subpoenaed for use in civil litigation or family law proceedings, and Securus has already suffered a data breach (although reports do not indicate that any electronic messages were implicated).88

It is likely that as technology develops, providers will collect more data. For example, if someone receives a Global Tel*Link call on a mobile phone, GTL may capture the geographic location of the recipient during the call and for one hour after the call ends, and will retain such data for a year.89 To the extent that electronic messaging develops into a mobile phone app-based service, similar issues could arise in connection with messaging data.

Although the likelihood and consequences of a data breach are somewhat uncertain, one thing is clear: many providers have attempted to disclaim any legal obligation to protect users’ data. Securus’s terms state that customers cannot obtain any type of damages for any injury, including data breaches.90 Smart Communications and Tech Friends also use language that disclaims any liability for data breaches.91 Telmate’s terms require users to waive claims of any kind against Telmate.92

Data could also easily be used for new types of analytic processes that present grave privacy concerns. With the proliferation of data, law enforcement agencies have been experimenting with database algorithms that attempt to predict someone’s likelihood for violence or other criminal behavior.93 In fact, Telmate has already patented a system that can give judges, prosecutors, and law enforcement agencies a computer-created “threat level” based on a person’s communication and transaction history.94 People who have studied this type of “predictive” law enforcement have warned that agencies typically do not have procedures to guard against “noisy” data that can lead to unreliable and inaccurate analyses.95 Legislatures and courts need to develop appropriate protections to prevent unfair and inaccurate profiling of incarcerated and free-world users.

One major uncertainty with respect to data privacy is whether prison-based electronic messaging services are subject to the Stored Communications Act (SCA).96 Congress enacted the SCA in 1986, and many experts have argued that it is in need of updating to reflect current technologies; nonetheless, it is still the law.97 Few would dispute that correctional facilities should be able to inspect incoming and outgoing messages (other than those protected by attorney-client privilege), and the SCA does not prohibit such inspection. The statute does, however, prescribe procedures that must be followed before an electronic communications provider can disclose user information. It does not appear that any facilities or providers currently follow those procedures, which raises questions regarding the use of messaging data in criminal prosecutions.98

Ownership of contents

Letters to and from people in prison have occasionally proven to be important historic or literary works.99 True, the majority of electronic messages probably cover mundane topics and are of interest only to the correspondents. Even so, this does not mean there will not be exceptions. As a matter of fairness and dignity, people in prison (and their families) should have the same rights to collect and publish their electronic correspondence as they do with postal mail. Unfortunately, electronic messaging contracts are often set up so that correspondents relinquish some or all of their intellectual property rights.

The most extreme example is Prevatek’s terms of service, which specify “[a]ll communication, postings, and uploads to this site become the exclusive property” of the provider.100 Securus also claims ownership of all messaging data (although the term is ill-defined).101 Other providers (including Telmate and Smart Communications)102 acknowledge that users retain ownership of intellectual property, but require users to grant a perpetual and irrevocable license to the provider (meaning the provider can then do whatever it wants to with the information). Turnkey goes so far as to require users to consent to Turnkey’s use of message contents in marketing materials.103

Protecting attorney-client privilege

Some companies expressly refuse to protect privilege for any messages sent on their systems.104 Others offer special service to attorneys (wherein privilege is purportedly honored)105 although it remains to be seen how robust the data protections actually are.106 To the extent that an electronic messaging system does not allow protected privileged communications, then the system is of limited use, since communicating with an attorney is critically important to many people held in prisons and jails. On the other hand, if a system does allow privileged communications, then the protection of such messages must be reliable and absolute. Users must be able to hold providers legally accountable for the intentionally or accidental disclosure of privileged communications.

IV. Recommendations

A. Federal Communications Commission

The FCC has already noted there “is little dispute that the ICS market is a prime example of market failure.”107 There is accordingly no reason to think that the advanced ICS market is any different. In fact, the industry has been fairly straightforward that future revenue growth must come from evasion of price regulation through alternative technologies.108 The FCC should ensure fair and reasonable rates and practices by adopting the following regulations covering electronic messaging services:

- Reasonable rates. Per-message charges should be reasonable (particularly in relation to any applicable character limits) and should be based on providers’ costs.

- Payment rules and ancillary fees. Subject electronic messaging service to the same ancillary fee and payment rule regulations that are applicable to telephone ICS.

-

Reasonable terms of service. Prohibit abusive terms in take-it-or-leave it terms of service contracts. At a minimum:

- Require all electronic messaging providers to publicly file terms of service with the FCC.

- Categorically prohibit mandatory arbitration, class-action bans, and exculpatory clauses.

- Establish a complaint process to accept and evaluate consumer complaints.109

-

Baseline terms. If a correctional facility decides to use electronic messaging, certain minimum standards should be enforced, such as:

- Compliance with the Stored Communications Act.

- Protection of attorney-client privilege.

- Compliance with unclaimed property laws (with respect to unused account balances).

- Any account balances should not expire and should be usable to communicate with any approved recipient.

B. State Legislatures and Public Utility Commissions

Because of the potential cost savings arising from electronic messaging, when state legislatures or local governments are exercising their budget-making authority, they should ensure that electronic messaging is paid for by the contracting agency, with no user fees.

State legislatures should enact statutes that specifically authorize electronic messaging in correctional facilities and impose necessary safeguards. Such legislation should, at a minimum:

- Require that any facility using electronic messaging must provide equal or greater access to postal mail.

- Repeal any statutory bans on incarcerated people’s internet access, and allow correctional administrators to decide what technologies should be used for educational programming, visitation, communication, and recreational activities.

- Require providers to disclose to users, upon request, any information derived from electronic messaging that is used or shared for any purpose other than message delivery.

Finally, to the extent that the FCC does not enact any of the measures enumerated in the previous section, state public utility commissions should fill this gap.

C. Correctional Administrators

Consumer protection should ideally come from financially disinterested oversight bodies like legislatures or regulatory agencies. That said, prison and jail administrators have immense power in the contracting process, and should use this power to ensure that consumer rights are not needlessly sacrificed in the name of profit-seeking. Some common-sense best practices that agencies can use when selecting an electronic messaging vendor include the following:

- Take responsibility for data security. Agencies often do not insist on contractual provisions that clarify ownership of electronic files or prohibit providers from using data for purposes other than fulfilling their duties under the contract. These are basic provisions that should be in all agreements. In addition, correctional administrators should scrutinize end-user terms of service and privacy policies and ensure that users’ personal information is protected from sale or transfer to third parties.

- Ensure adequate equipment. Electronic messaging systems can only realize their potential benefits if incarcerated users have meaningful access to the necessary computer hardware. In the case of shared computers, correctional administrators should research usage patterns and determine the optimum user-to-kiosk ratio and ensure that contracts reflect these needs.

- Require advance approval of rate increases. As stated in the previous section, electronic messaging should be free of charge to end users. Nonetheless, if a facility does use a fee-based service, the contract with the provider should spell out all applicable fees including any ancillary charges, and should give the facility absolute discretion to approve or disapprove any fee increases during the life of the contract.

- Interoperability. Facilities should not sign a contract with a provider without first determining that system data is in a standardized format that can be transferred to other providers in the future. Failure to ascertain this at the outset of a contract could make switching to a different provider much more difficult.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible thanks to the generosity of the Prison Policy Initiative’s individual donors who support strengthening the bonds between incarcerated people and their families. We are grateful to the Human Rights Defense Center/Prison Legal News for sharing their data and to Jacob Mitchell for sharing his expertise of email infrastructure. We thank Bob Machuga for designing the cover, Elydah Joyce for creating figures 1 and 2, and Leah Sakala for thinking of the creative title.

The author would also like to think Aleks Kajstura, Bernadette Rabuy, and Peter Wagner for their invaluable editorial support throughout the research and drafting process.

About the Author

Stephen Raher is a Pro Bono Legal Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative and works as an attorney in Portland, Oregon. Prior to practicing law, he was a public radio reporter, and helped to found the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, where he worked for several years as a policy analyst. Stephen holds a master of public administration from the University of Colorado and a juris doctor from Lewis & Clark Law School. His prior work for the Prison Policy Initiative includes comment letters on jail “release cards” and the Bureau of Prison’s proposal to weaken financial privacy protections.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to challenge over-criminalization and mass incarceration through research, advocacy, and organizing. We show how the United States’ excessive and unequal use of punishment and institutional control harms individuals and undermines our communities and national well-being through filling data gaps in the national movement for criminal justice reform and sparking targeted campaigns.

The Easthampton, Massachusetts-based organization is most famous for its work documenting how mass incarceration skews our democracy and how the prison and jail telephone industry punishes the families of incarcerated people. The organization’s groundbreaking reports on the prison and jail phone industry, and on video visitation, as well as its work with SumOfUs to collect 60,000 petitions for the Federal Communications Commission have been repeatedly cited throughout the FCC’s orders.

Footnotes

See In the Matter of Rates for Interstate Inmate Calling Services, WC Docket No. 12-375, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 28 FCC Rcd. 14107 (2013) [hereinafter “First R&O] (setting forth the need for reform, establishing interim rate caps for interstate calls, and establishing framework for just, reasonable, and fair ICS rates); Second Report and Order and Third Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 63 Commc’ns Reg. 1081 (2015) [hereinafter “Second R&O”] (adopting rate caps for inter- and intrastate calls, regulating ancillary fees, and requesting comments on advanced ICS technologies). ↩

Email is a distributed communication system with no central authority, much like international postal mail. Email users generally send, receive, and access messages via a mail user agent (MUA). Upon telling the MUA to send a message, data is packaged and relayed through a series of mail transfer agents (MTAs) until finally delivered to the recipient’s MUA. Email service providers all support this architecture, and interoperate seamlessly with other email service providers. All of this is built on openly available protocol standards, enabling a fluid market for competition among providers. See generally, Internet Mail Architecture (Network Working Group RFC 5598, Jul. 2009). In contrast, the proprietary portals upon which electronic messaging systems rely are not part of this standard architecture. ↩

The most notable exception to flat-fee pricing is the Federal Bureau of Prison’s TRULINCS system, which charges incarcerated users a per-minute fee for use of the system. See infra, text accompanying notes 35-36. ↩

JPay does have an app that allows non-incarcerated users to use messaging service on their mobile phones. JPay appears to be the only provider to offer such software at this time. ↩

For a detailed discussion of the benefits of, and challenges to, in-person visitation, see Bernadette Rabuy & Daniel Kopf, Separation by Bars & Miles: Visitation in State Prisons (Prison Policy Initiative, Oct. 20, 2015). ↩

See generally, Drew Kukorowski, The Price to Call Home: State-Sanctioned Monopolization in the Prison Phone Industry (Prison Policy Initiative, Sept. 11, 2012) and Drew Kukorowski, Peter Wagner & Leah Sakala, Please Deposit All of Your Money: Kickbacks, Rates & Hidden Fees in the Jail Phone Industry (Prison Policy Initiative, May 8, 2013). ↩

Id. ¶ 60. ↩

Id. ¶ 22. ↩

Id. ¶¶ 123-132. ↩

Id. ¶¶ 296-307. ↩

Indeed, the historical significance of written communication from prison long predates the founding of the United States. Theologian and professor of religious history W. Clark Gilpin has written extensively about letters from prison (many of which were smuggled out, past censors) and the role they play in the history of Christianity. See W. Clark Gilpin, “The Letter from Prison in Christian History and Theology” (Religion & Culture Web Forum, Jan. 2003). ↩

U.S. Postal Serv., Ofc. of Inspector General, “Management Alert—Substantial Increase in Delayed Mail” (Rpt. No. NO-MA-15-004, Aug. 13, 2015); U.S. Gov’t Accountability Ofc., “U.S. Postal Service: Actions Needed to Make Delivery Performance Information More Complete, Useful, and Transparent” (Rpt. GAO-15-756, Sept. 2015). ↩

See generally, Leah Sakala, Return to Sender: Postcard-Only Mail Policies in Jail (Prison Policy Initiative, Feb. 7, 2013). ↩

E.g., Prison Legal News v. Columbia County, 942 F.Supp.2d 1068, 1088 (D. Or. 2013) (“The postcard-only policy blocks one narrow avenue for the introduction of contraband—within envelopes—at too great an expense to the First Amendment rights of inmates and their correspondents.”); see also Sakala, supra note 15, at 8 (collecting cases). ↩

Santa Barbara County, California banned incoming letters and packages in March 2013, but repealed the policy several months later, after a similar ban in another county was struck down by a federal court. See Leah Sakala, “Victory: Santa Barbara County scraps harmful jail letter ban policy” (Oct. 3, 2014). Simultaneous with the adoption of the letter ban, Santa Barbara County added electronic messaging to its contract with Keefe Commissary Network, see infra note 59. Knox County, Tennessee also bans incoming mail other than postcards, although this policy is currently the subject of litigation. Alex Friedmann, “PLN challenges postcard-only policy at jail in Knoxville, TN,” Prison Legal News (Nov. 2015) at 58. Knox County has used electronic messaging since at least 2012. See Knox County Contract with PayTel, infra note 56. ↩

There are two notable exceptions to the dominant models. First, TurnKey (InmateCanteen.com) uses a system wherein a non-incarcerated user logs into the website and pays for a message. Upon receipt of payment, the system issues a unique single-use email address to the user, who then composes and sends the message to the single-use address. The message is then delivered to the incarcerated user (either on paper or electronically, depending on which type of system the facility uses). If the facility uses a two-way system, the incarcerated user can reply, but only if the free-world user has prepaid for a reply. TurnKey’s electronic messaging doesn’t appear to be among the industry leaders (in terms of number of users), but the company does have contracts with facilities in at least a dozen states. Second, VendEngine Dev’s “Inmate Email” program is “one way,” but only allows outgoing messages. See VendEngine Dev., “VendEngine Adds Inmate Email” (Aug. 9, 2013). Prison Policy Initiative was not able to determine how many facilities participate in VendEngine’s program. ↩

Bernadette Rabuy & Peter Wagner, Screening out Family Time: The For-Profit Video Visitation Industry in Prisons and Jails (Prison Policy Initiative, Jan. 2015) at 4. ↩

Derek Gilna, “Companies Pitch Tablets for Prisoners to Maintain Family Ties, Aid in Reentry…and Generate Profit,” Prison Legal News (Jul. 2015) at 42. ↩

U.S. Patent Application 13/842,031, “Inmate Network Priming” (filed Mar. 15, 2013 by Telmate, LLC) [Exhibit 1, at 84]; U.S. Patent Application 13/843,968, “Message Transmission Scheme in a Controlled Facility” (filed Mar. 15, 2013 by Telmate LLC) [Exhibit 1, at 110]. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has preliminarily rejected both of these patent applications; however, Telmate has amended the applications and asked for reconsideration. ↩

A Jailhouse Lawyer’s Manual 519 (Columbia Human Rights L. Rev., 9th ed. 2011). ↩

Titia A. Holtz, Note, Reaching out from behind Bars: The Constitutionality of Laws Barring Prisoners from the Internet, 67 Brook L. Rev. 855 (2001-02) (Arizona prohibits any person incarcerated in the state from directly or indirectly accessing the internet. Ohio law prohibits internet access, but does have an exception for educational programs); Jailhouse Lawyer, supra note 23, at 520 (stating that Minnesota, California, Kansas, and Wisconsin have also enacted similar statutes). ↩

The true number of firms in the market is now ten, because two of the companies listed in table 1 have been acquired by Securus and Global Tel*Link, see infra, notes 27 and 32. There are two additional companies that claim to provide electronic messaging in U.S. facilities, but Prison Policy Initiative was unable to verify these claims. First, UK-based company Core Systems (NI) Ltd. specializes in tablet-based prison technology, and offers a messaging service. The company has expressed a desire to expand to the United States, “the largest prison market in the world.” See http://www.coresystems.biz/core-systems-md-is-targeting-the-us/. In a 2014 publication targeting potential investors, Core Systems claimed to hold a “state-wide” contract in the U.S., serving “a prisoner population of over 22,000” [Exhibit 2], but Prison Policy Initiative has been unable to identify the jurisdiction. Second, a company called Connex Information Systems, Inc. claims to offer a service called “Mail My Inmate,” but does not reveal which facilities, if any, use the service. Connex appears to specialize in payment processing for jails. ↩

See Securus Technologies, et al. v. FCC, et al, D.C. Cir. Case No. 13-1280; Global Tel Link v. FCC, et al., D.C. Cir. Case No. 13-1281 (consolidated with Securus v. FCC). ↩

Press Release, “Global Tel*Link Announces Acquisition of Renovo Software” (Jun. 23, 2014). ↩

Securus Technologies, “Public Lender Presentation” (Apr. 15, 2015) [Exhibit 3] at 26. Along the same lines, Smart Communications sued a company (ATN, Inc.) in 2014, with which it had formed a partnership to market Smart Communications’ kiosk system to facilities. Smart Communications explained the genesis of the partnership as follows: ATN was an ICS provider specializing in telephone service, and Smart Communications alleged that ATN’s “desire to partner with [Smart Communications] was motivated by a need to find new revenue streams to replace revenues that it believed it would lose as a result of complying with the new FCC rules.” Smart Commc’ns US v. ATN, Inc., Case No. 8:14-cv-01630 (M.D. Fla.), Complaint ¶ 37. ↩

See In the Matter of Implementation of the Pay Telephone Reclasification and Compensation Provisions of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, CC Docket No. 96-128, Third Report and Order, and Order on Reconsideration of the Second Report and Order, 14 FCC Rcd. 2545 (1999) ¶ 56 (“[T]he vast majority of the costs of providing payphone service are fixed and common costs, and there is no one economically correct way to allocate such costs among the different types of calls that may be made from a payphone. Economic theory does suggest, however, that the costs of one service should not be cross-subsidized by another service… . In order to avoid a cross-subsidy between two such services that are provided over a common facility, each service must recover at least its incremental cost, and neither service should recover more than its stand-alone cost.” (footnotes omitted)). ↩

See generally, Tim Barker, “Prison services are profitable niche for Bridgeton company,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Feb. 15, 2015) (“In 2012 … Keefe Commissary Network, along with two other subsidiaries, recorded a robust $41 million net income on $375 million in sales.”). ↩

See generally, Stephen Raher, “Proposed Amendments to Regulation E: Curb exploitation of people release from custody” (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Docket No. CFPO-2014-0031, comment dated Mar. 18, 2015). ↩

Securus Technologies, Inc. to Acquire JPay Inc. (link no longer available),” press release (Apr. 15, 2015). ↩

Securus Technologies, Inc, Proposal for Inmate Communications and Management System (Knox County RFP No. 2189) (Jun. 18, 2015) [Exhibit 4], at 9 (“As we recognize the exceptional work currently done by Tech Friends at Knox County, Securus choose [sic] to partner with them to offer a combined solution that will meet and exceed all of the RFP requirements.”). ↩

Advanced Technologies Group, Frequently Asked Questions (accessed Jan. 2, 2016). ↩

Id. ↩

See “Inmate Agreement for Participation in TRULINCS Electronic Messaging Program,” (Fed. Bureau of Prisons Form BP-A0934, Rev. Jun. 2010). ↩

Other than the BOP’s TRULINCS system, which receives some funds from the BOP’s Inmate Trust Fund (see Fed. Bureau of Prisons, “TULINCS Topics: Funding” (accessed Jan. 16, 2016)), the only example that Prison Policy Initiative found of a correctional facility paying for service was in a contract that covers voice telephone, video visitation, electronic messaging, and release card service. See Inmate Telephone Services Agreement, between Inmate Calling Solutions, LLC and Champaign County (Oct. 3, 2013) [Exhibit 5] (requiring the county to pay a $75,000 “installation fee” for installation of forty phones, thirty-three communications kiosks, and two financial kiosks). ↩

Inmate Telecommunication Location Agreement, between Telmate, LLC and Oklahoma County Board of County Commissioners (Jan. 28, 2015) [Exhibit 6] at ¶ 6. The contract calls for an annual “technology grant” of $100,000 during the life of the contract, not to exceed a total of $500,000. The District Attorney who reviewed the contract for the Sheriff’s Office approved the agreement as to form, but expressed “concern” at the lack of guidelines on how the “grant” was to be used. ↩

Washoe County, Nevada provided an “Inmate Commissary Equipment and Accounting System Service Agreement” with JEMCOR, Inc. (Jan. 25, 2013) [Exhibit 7], which provides for 25 kiosks, and does mention electronic messaging service (and site commissions), but does not clarify Tech Friends’ role, although the county did provide a separate Tech Friends contract that covers money transfer services. Cowley County, Kansas provided an “Amendment to Food Service Contract between Cowley County Kansas and CBM Managed Services” (May 1, 2008) [Exhibit 8] and sent a helpful written explanation that in August 2013, the county allowed Tech Friends to offer messaging service through computer kiosks that are part of the CBM Managed Services contract. Shelby County, Alabama provided a “Service Agreement” with Kimble’s Commissary (Sept. 9, 2015) [Exhibit 9] that provides for 22 kiosks with “email” (apparently provided through Tech Friends). Wake County, North Carolina provided a “Services Agreement” with Oasis Management Systems, Inc. (Jul. 1, 2015) that provides for 16 kiosks, but does not mention electronic messaging. ↩

Lincoln County, Missouri provided a one-page “Automatic Debit or Credit Agreement Form” (Jun. 8, 2015). ↩

Prison Policy Initiative identified two instances of no-fee electronic messaging. First, the TRULINCS system in the federal Bureau of Prisons does not charge fees to free-world users, but incarcerated users do have to pay. See supra, note 35 and accompanying text. Second, Smart Communications (which is a relatively small provider, see supra, section II.A) provides incarcerated users two free messages per week, potentially funded by online advertising. See, e.g., Electronic Messaging System Agreement, between Smart Communications Collier, Inc. and Carroll County (AR) Sheriff’s Office (Jun. 16, 2015) [Exhibit 10] at § 2.6. ↩

As discussed in section I.B, some electronic messaging services are “one way,” only allowing non-incarcerated people to send inbound messages to people in jail. In these cases, all fees are paid by the non-incarcerated user. In the case of two-way messaging, systems often require all fees to be paid by the non-incarcerated party. Because the precise mechanism of payment is typically not addressed in the contract between the provider and the facility, it is unclear how many systems allow incarcerated persons to pay from their commissary accounts. Some systems do allow for incarcerated users to pay. E.g., Agreement for Inmate Electronic Messaging and Kiosk Services, between JPay Inc. and Kansas Dept. of Corr. (Jul. 1, 2013) [Exhibit 11] at ¶ IV(H)(3) (incarcerated users can pay for messaging, or non-incarcerated users to prepay for the cost of an incarcerated correspondent’s reply); Knox County Proposal, supra note 33, at 151 (“Tech Friends[‘] messaging system allows the inmate to purchase the message or to request that the receiving family member fund the message exchange.”). ↩

According to the user interface at JailATM.com (operated by TechFriends), messages to people at the jail in Buffalo County, Wyoming, are five cents each. This jurisdiction is a clear outlier, since per-message prices are rarely less than twenty cents. ↩

Master Services Agreement, between Securus Technologies, Inc. and Benewah County (Idaho) Sheriff’s Department (Mar. 29, 2013) [Exhibit 12] at 8. ↩

InmateCanteen.com, Purchase Screen [Exhibit 13 at 2]. ↩

InmateCanteen.com, Communications Disclosure [Exhibit 13 at 3]. ↩

Securus, Payment Screen [Exhibit 13 at 4]. ↩

At least one state prison system has attempted to take a closer look at provider costs, but was unsuccessful. See Sidebar: The High Cost of No-Cost Contracts. ↩

Am. Corr. Ass’n, “Public Correctional Policy on Adult/Juvenile Offender Access to Telephones (site not longer functional)” (Feb. 1, 2011). ↩

JPay, Inc, Best and Final Offer, RFP #08-IGWF-80, submitted to Pennsylvania Dept. of Corr. (Sept. 1, 2009) at 3 [see page 127 of Exhibit 14] (“Typically, JPay strives to price each message under that of a US postal stamp.”). ↩

JPay, Inc., Email Webpage (not dated). ↩

39 U.S.C. § 3622(c)(2). ↩

E.g., First R&O, supra note 1, ¶ 41 (“[A] former Commissioner on the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission, Jason Marks, has stated that the interstate ICS market is characterized by ‘reverse competition’ because of its ‘setting and security requirements.’ He further asserts that ‘reverse competitive markets are ones where the financial interests of the entity making the buying decision can be aligned with the seller, and not the buyer’ and that such competition ‘is at its most pernicious in the inmate phone service context because buyers not only do not have a choice of service providers, they also have strong reasons not to forego using the service entirely.’”). ↩

E.g., Knox County Contract with PayTel, infra note 57, at ¶ 2(f) (“Contractor and Vendor shall be responsible for the determination of transaction and service fees which are subject to review and approval by County. Approval of any increases will not be unreasonably withheld.”). ↩

E.g., Agreement for Inmate Electronic Messaging, supra note 43, Attch. C (messages cost 35 cents, with DOC receiving a five-cent commission per message; there is a thirty-five cent fee per attachment, and a thirty-five cent fee to print messages, with DOC receiving five cents of each such fee); Inmate Telephone Services Contract, between Inmate Calling Solutions, LLC and Williamson County (TX) (Aug. 12, 2014) [Exhibit 15], Exh. D (Messages cost sixty cents, with county receiving twenty-cent commission per message. This contract also covers voice telephone service, which is subject to a different commission system: the county receives a commission of 84.1% of gross telephone revenue, with a guaranteed minimum annual commission of $555,000. The amount of the guaranteed minimum commission suggests that kickbacks from electronic messaging are a comparatively minor revenue source for the county). ↩

The majority of percentage-based contracts that Prison Policy Initiative obtained call for commissions of 10% to 20%. The two notable outliers are Oklahoma County, Oklahoma (see Inmate Telecommunication Agreement, supra note 38, at ¶ 5(a) (Telmate pays a commission of 50% of gross revenue from video system; it appears that electronic messaging is considered part of the video system)) and Knox County, Tennessee (see Amendment to Contract No. 08-397, between Knox County (Tennessee) and Pay Tel Commc’ns, Inc. (Oct. 22, 2012) [Exhibit 16] (Under this contract, which has or is about to expire, Pay Tel provided general ICS and subcontracted with Tech Friends for electronic messaging. Pay Tel paid a 43.75% commission on “all billable revenue generated from the video visitation system,” and it appears that electronic messaging was considered part of the video system.). ↩

Praeses is a company that advertises itself as “providing rate validation and general consulting practices” to correctional facilities.” Comments of Praeses LLC (WCC Dkt. No. 12-375, Jan. 12, 2015) at 3. ↩

Praeses LLC, “Monthly Facility Summary Report” (Nov. 2013 through Feb. 2015) [Exhibit 17]. ↩

Santa Barbara County (CA) Bd. of Supervisors, Keefe Commissary Network Contract Amendment (Apr. 1, 2014) [Exhibit 18] at 3. ↩

Peter Wagner & Bernadette Rabuy, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2015 (Dec. 8, 2015). ↩

Peter Wagner, Aleks Kajstura & Lindsie Trego, “ICS Companies Seizing Unclaimed Funds as a Way to Fleece Families and Facilities ” (WCC Dkt. No. 12-375, Jan. 12, 2015). ↩

TW Vending, Inc., Services – Inmate E-mail (accessed Jan. 3, 2016). ↩

Smart Communications US, Inc., Postal Mail Elimination System (accessed Jan. 3, 2016). ↩

Id. Smart Communication’s website provides no details about the alleged patent application. Searches of U.S. Patent and Trademark Office applications and issued patents using Smart Communications or relevant keywords (“postal mail,” “elimination,” “secure facility”) revealed no such application. ↩

Telmate, LLC, Response to Allegan County (MI) RFP #10151: Inmate Phone & Video Visitation System (Aug. 29, 2013) [Exhibit 19], Attch. A, at 45. ↩

Id., Attch. A, at 19 (Telmate says that its messaging system can help “[p]revent contraband, such as methamphetamine laced ink, from reaching your inmates through traditional mail.” A search of news databases does not reveal any coverage of such ink, and the only responsive result in a general internet search is Telmate’s own webpage. Even if drug-infused ink does exist, it is not clear how frequent of a problem it is for correctional facility mailrooms). ↩

See generally, Saneta deVuono-Powell, et al., Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families (Sept. 2015). ↩

Peter Wagner, “The demographics of computer ownership and high-speed internet access” (Mar. 17, 2015). ↩

See generally, Jailhouse Lawyer, supra note 23, at 507-519. ↩

Ironically, Smart Communications sometimes makes facilities contractually agree that users will have equal access to phone and messaging. See Electronic Messaging System Agreement, supra note 42, § 6.1. This is in Smart Communications’ financial interest, because the company provides messaging, but not phone service. Because incarcerated users do not have the negotiating leverage that ICS providers do, they cannot negotiate for similar parity provisions to protect their ability to communicate. ↩

18 U.S.C. § 1708; 39 U.S.C. § 404(c). ↩

Jordan Smith & Micah Lee, “Not So Securus,” The Intercept (Nov. 11, 2015). ↩

See generally, Postal Regulatory Comm’n, Report on Universal Service and the Postal Monopoly (Dec. 19, 2008). ↩

Companies that require users to be at least thirteen probably pick this age because of the collection of information about children under thirteen is regulated under the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, 15 U.S.C. § 6501, et seq. Rather than burying a restriction in terms of service that—given the demographics of the user base—will often be ignored, messaging providers should instead take the necessary steps to comply with this law. ↩

Global Tel*Link, Privacy Statement (Mar. 30, 2015) ¶ 5(D) [Exhibit 21A]. ↩

Securus Technologies, Privacy Policy (not dated) ¶ B(1) [Exhibit 21N]. ↩

Securus Technologies, Secure Instant Messaging Terms & Conditions (not dated) §§ 11.2 & 14 [Exhibit 21O]. ↩

Smart Communications, Privacy Policy (Jan. 7, 2014) [Exhibit 21R]. ↩

Amendment #2 to Electronic Letter Service Agreement, between JPay, Inc. and Colo. Dept. of Corr. (Feb. 4, 2011) [Exhibit 20] ¶ 6(b). ↩

Electronic Letter Service Agreement, between JPay, Inc. and Colo. Dept. of Corr. (Feb. 26, 2010) [Exhibit 20] ¶¶ 2 and 8 ↩

Id. ¶ 6. ↩

Id. ↩

E.g., Jail Service Agreement, between TurnKey Corrections and Cherokee County (KS) Sheriff (Jul. 14, 2015) [Exhibit 22] at 4. ↩

Securus Technologies, Secure Instant Messaging Terms & Conditions, supra note 78 at ¶ 12(b). ↩

Smart Communications, Terms of Service (Apr. 11, 2012) § 18 [Exhibit 21S]; Tech Friends, Terms of Agreement (no date) at 3 [Exhibit 21I]. ↩

Telmate, Terms of Service (no date) ¶¶ 87-88 [Exhibit 21U]. ↩

Justin Jouvenal, “The new way police are surveilling you: Calculating your threat ‘score,’” Wash. Post, Jan. 10, 2016. ↩

U.S. Patent 9,117,171, “Determining a Threat Level for One or More Individuals” (Aug. 25, 2015) [Exhibit 1 at 2]. ↩

Walter L. Perry, et al., Predictive Policing: The Role of Crime Forecasting in Law Enforcement Operations (RAND Corp. 2013) 89 (“When dealing with information about people—which are especially likely to be noisy and conflicting—law enforcement agencies might benefit from a formal process to address data noise and confusion. We have found little evidence of such processes in the law enforcement community, however.”). ↩

18 U.S.C. § 2701-2711 (sometimes referred to as the Electronic Communications Privacy Act). ↩

See generally Orin S. Kerr, A User’s Guide to the Stored Communications Act, and a Legislator’s Guide to Amending It, 72 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1208 (2004). ↩

See Jeffrey M. Heggelund, Prisoner Interception: A Costly Turnover?, 7 Loy. J. Pub. Int. Law 57 (2005) (The author, an attorney and former undercover narcotics officer, argues that that unlawful disclosure of prison telephone recordings can endanger public safety because it could complicate prosecution of related crimes.). ↩