Research confirms that prison food is not just gross; it is often nutritionally inadequate. A recent report from Washington provides new evidence and our policy analyst examines the public health costs.

by Wendy Sawyer,

March 3, 2017

This past fall, a new report from Prison Voice Washington detailed the decline in food quality served in the state’s correctional facilities. While incarcerated people often voice complaints about (very real) quality-of-life issues related to food service, there is a broader public health concern here: the long-term health consequences of forcing incarcerated people to consume unhealthy food.

This past fall, a new report from Prison Voice Washington detailed the decline in food quality served in the state’s correctional facilities. While incarcerated people often voice complaints about (very real) quality-of-life issues related to food service, there is a broader public health concern here: the long-term health consequences of forcing incarcerated people to consume unhealthy food.

The Prison Voice Washington report

The report from Prison Voice Washington reveals how changes in food service at the Washington Department of Corrections violate the state’s own Healthy Nutrition Guidelines. Since turning over food service to the Department’s business arm, Correctional Industries, the quality of food has deteriorated and culinary job opportunities that require actual cooking skills have dried up. People incarcerated in Washington are now being forced to eat unhealthy, processed food from its central food factory.

The downturn in prison food quality can be blamed on larger trends toward industrialization and privatization. Industrialization, as exemplified by Washington state prisons, replaces cooking from scratch with processed foods that may only require reheating before serving. “When the Department of Corrections turned over responsibility for food services to Correctional Industries…, it substituted 95% industrialized, plastic-wrapped, sugar-filled ‘food products’ for locally prepared healthy food.”

Highly processed and hastily prepared food is typical of privatized food service as well. Nationally, much of prison food is outsourced to two large private corporations, Aramark Correctional Services and Trinity Services Group, the targets of increasing numbers of inmate grievances and embarrassing lawsuits. While under contract with Aramark, for example, kitchens in Michigan and Ohio prisons reportedly “served food tainted by maggots… rotten meat… food pulled from the garbage…[and] food on which rats nibbled.”

What’s especially disheartening about the state of food in Washington’s prisons is that not long ago, incarcerated people in each facility were preparing food fresh from scratch, using ingredients grown at the prisons or bought from local farmers. According to Prison Voice Washington, “Prisons grew their own food, maintained dairies and bakeries, and the food… was cooked locally.” Today, there is just one massive farm, which Correctional Industries touts as part of its “closed-loop grain-to-baker-to-prison food chain.” The most recent harvest it reports online is 200 acres’ worth of dry peas. There are still gardening programs at some facilities, but according to Prison Voice Washington, “a few small gardens… [present] a rosy veneer of sustainability and fresh produce to circumvent any real scrutiny of the bleak food reality.”

Their point? The Department is capable of doing a better job, and had done so as recently as 2009. Short-sighted administrators looking to save a few cents per meal have made a bad deal with Correctional Industries, trading a fresh, healthy food service program for highly processed foods that make incarcerated people sick.

To make their case, the authors of the Prison Voice Washington report include an incredible amount of evidence including invoices, nutrition labels, and four appendices of order forms and menus. They show that:

- Incarcerated people in Washington do not receive minimum requirements for fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, or milk.

- Incarcerated people are fed more than the recommended amounts of refined starches, added sugars and sodium.

- The DOC is fully aware of the nutritional shortcomings of its menu, so it supplements meals with fortified drink powders. These are often left untouched, so even those supplements do little to make up for the lack of nutrients in the actual food served.

- Besides the prison menu, the only other choices incarcerated people have are the products available through the commissary, where more than 90% of available products “are very unhealthy, and are categorized as ‘Avoid’ in the [State’s] Healthy Nutrition Guidelines for Vending Machines.” Even the instant oatmeal is the highly sweetened, low fiber variety on the “not recommended” list.

Again, this is all at odds with Washington’s ostensible commitment to improving nutrition. In most states, correctional agencies follow federal guidelines (or attempt to), without so much as lip-service to providing anything above a minimum standard. Washington, however, has the most comprehensive food standards of any state, although many other cities and states have adopted their own standards for food served or sold at other public agencies. The only other state with nutritional standards that apply to correctional facilities is Massachusetts; New York City and Philadelphia have sweeping city-wide nutritional standards that apply to correctional facilities as well. The Prison Voice Washington report should serve as a model to hold other agencies accountable and ensure healthy foods are available to people in correctional facilities.

Other studies of prison food show that Washington’s failings are not unique

Washington’s DOC is certainly not unique; prisons and jails are notorious for serving terrible food. Prison meals are a favorite subject for colorful photo projects and personal experiments — even Buzzfeed has made one of their trademark videos about it. And research confirms that prison food is not just gross; it is often nutritionally inadequate:

- A menu analysis from a large county jail in Georgia found incarcerated people there were served a diet too high in cholesterol, saturated fat, and sodium, and too low in fiber and several micronutrients — all factors linked to an increased risk of heart disease.

- An analysis in South Carolina found similar deficiencies, and like the Washington study, found the menu too stingy in fruits, vegetables, and milk, and too reliant on starches.

- In a Michigan report, correctional officers reported frequent deviations from the menu, especially watering down recipes and serving small portions, making it impossible for people to get the nutrients agreed upon by contract.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that sodium is off the charts in U.S. prisons: in 1989 (the most recent year of available data) federal prisons were serving a diet with 10,000 mg of sodium per day; by 1995, their goal was to reduce it to 6,520 mg per day — still almost three times the recommended upper limit.

So yes, prison food tastes bad. But more importantly, it’s really bad for you.

The links between chronic disease and nutrition mean that prison nutrition matters

Incarcerated people are at increased risk of chronic diseases, but rather than using Food Services to help control both health problems and the costs of medical treatment, prisons exacerbate illnesses by serving and selling unhealthy foods. Half of all incarcerated people in state and federal prisons report having had a chronic illness and are “potentially at risk for future medical problems.” Nearly as many — 40% — report a current chronic condition. Considering 1) the prevalence of chronic illness in prisons, 2) the documented impact of diet on these diseases, and 3) the much lower cost of food compared to medical treatment, it is irresponsible and shortsighted of correctional agencies to prioritize cost-cutting over nutrition.

The most problematic correlations between prison food and health include:

- Weight: The most obvious link between food services and health is weight. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that three quarters of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons are overweight or obese. Other researchers have found that each period of incarceration increases an individual’s Body Mass Index, which is a measure of overweight and obesity. Prison food is part of the reason why: as we’ve seen, menu analyses have found that prisons and jails serve highly processed, unwholesome food, and offer primarily high-fat and sugary options for purchase. Even when the menu fits nutritional guidelines on paper, it is often prepared in ways that make it less healthy: Prison Voice Washington reports that food service workers “attempt to fry” ingredients, so entrees like meatloaf end up “literally soaked in oil and margarine.”

- Chronic diseases: In addition to excess weight, incarcerated people suffer disproportionately from chronic health conditions. 30% of incarcerated people have hypertension, 10% heart problems, and 9% diabetes — all higher rates than the general population. As the American Heart Association’s diets for heart disease and hypertension make clear, conditions like these can be prevented or even reversed to some extent by a nutritious diet. Instead, they are made worse by menus with too much sodium and fat and not enough fiber and essential nutrients from fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Racial health disparities: African Americans are more likely to suffer from hypertension and diabetes, and research points to disproportionate incarceration of African American men as a cause of these health disparities. “Incarceration may help structure obesity disparities,” according to one study, and “part of the reason African American men suffer worse health is that they spend more time on average in prison, a place that undermines health,” concludes another. By ignoring the negative effects of the unhealthy prison diet on this vulnerable population, states are willingly putting them at greater risk for premature death. Each year of incarceration reduces life expectancy by two years, and this is especially true for black men.

To be sure, prisons do provide “therapeutic” or “medical” diets, prescribed by health services staff. Unfortunately, the Washington study reveals that even the “lighter fare” diet would do little to help someone with a chronic illness; it includes an extra serving of vegetables, but even less protein. In any case, when half of the incarcerated population has a chronic illness, it would make sense for a nutritious, health-services-approved diet to be the norm, not the exception. (Thankfully, some agencies have figured this out for themselves: Pennsylvania uses the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ diabetic diet for its regular menu standards, and Massachusetts has created a healthier menu to minimize the number of special dietary menus needed.)

The budget is no excuse

The fact is, serving decent food is cheaper than serving unhealthy and unappetizing food in the long run. Considering the additional costs associated with poor food quality, the cost-cutting measures correctional agencies have taken around food services are fiscally short-sighted. For one thing, deteriorating food quality causes frequent security problems: when incarcerated people see that they are getting worse — or less — food than before, they protest in various ways — from dumping bad potatoes on the floor to strikes. Additional guards may be required to manage food service, not to mention the risks associated with large-scale protests like the coordinated prison strikes in the fall of 2016.

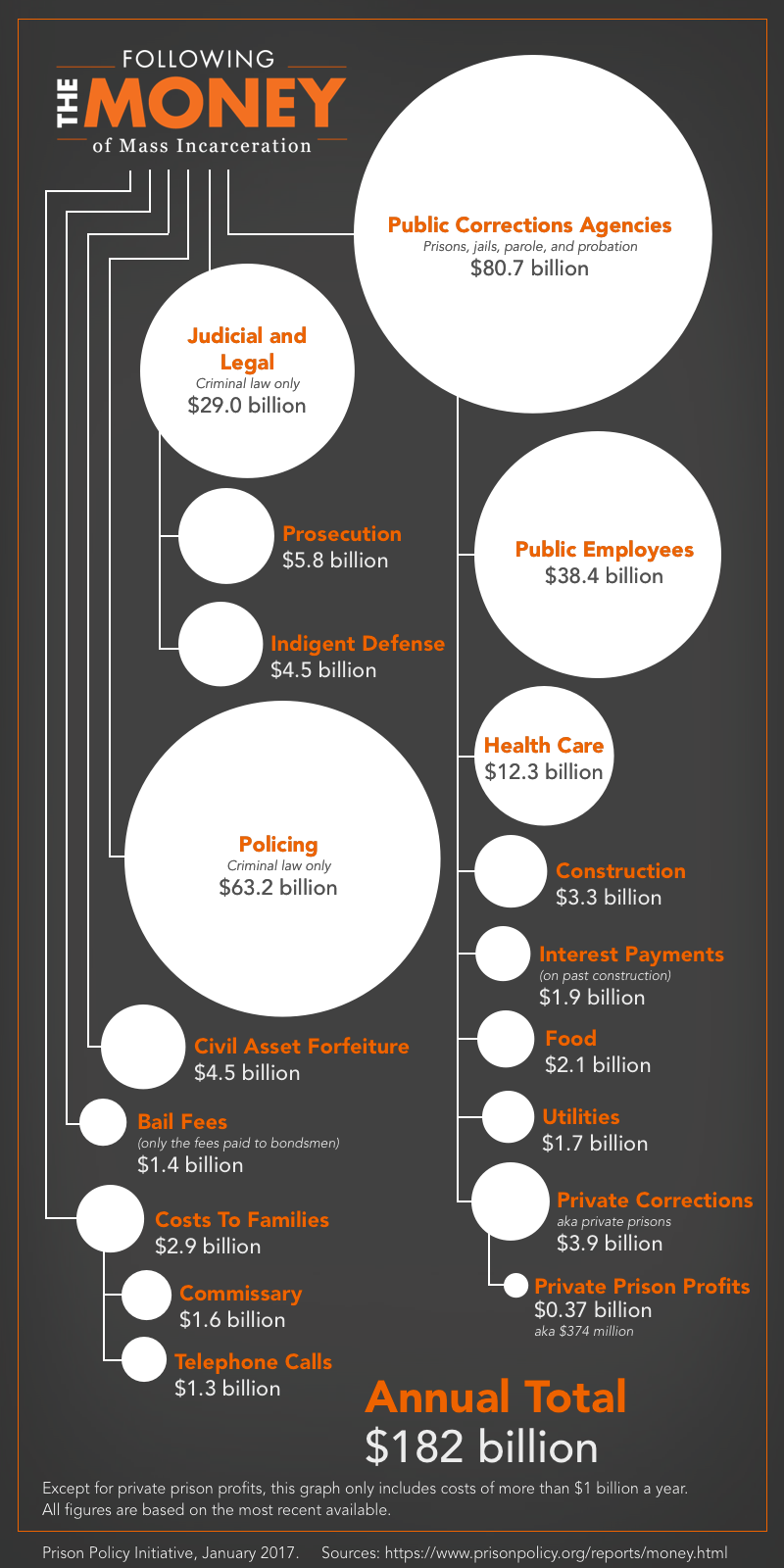

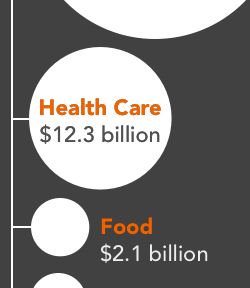

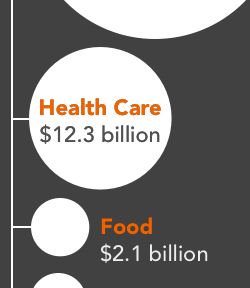

Food costs are also dwarfed by healthcare costs in prisons, so improving the nutritional quality of prison food would be a cost-effective way to improve inmate health. In our recent analysis of criminal justice costs, we found that correctional agencies spend almost six times more on health care than on food. Prison Voice Washington found that food costs make up less than 4% of the daily cost of incarcerating a prisoner — compared with healthcare, which accounts for 19% of the cost.

Food costs are also dwarfed by healthcare costs in prisons, so improving the nutritional quality of prison food would be a cost-effective way to improve inmate health. In our recent analysis of criminal justice costs, we found that correctional agencies spend almost six times more on health care than on food. Prison Voice Washington found that food costs make up less than 4% of the daily cost of incarcerating a prisoner — compared with healthcare, which accounts for 19% of the cost.

As the Washington authors note, even doubling the state food budget wouldn’t cost very much for the total budget and would be well worth it considering the additional healthcare costs related to chronic illness. The American Diabetes Association, for example, estimates that healthcare costs are 2.3 times higher for incarcerated people with diabetes. And overall, 86% of healthcare spending is for people with at least one chronic condition. As Prison Voice Washington concludes, “In the short run, healthy food does cost a little more — but unhealthy people cost a great deal more.”

Moreover, some states have begun to recognize that even “cost saving” moves toward industrialization and privatization aren’t worth the problems with food quality, security, and long-term health consequences. An audit of Florida’s Aramark contract found that its food costs were lower, quality was better, and more inmates actually ate the food when the Department operated its own food services program. And after struggling with a private contractor, Minnesota decided to return food services to in-house control in 2015, “providing real food for inmates even if it costs more money.”

Before long, incarcerated people’s health problems become community health problems

People who believe prison should be as punishing as possible may see little reason for facilities to serve much more than bread and water. But there is a practical reason to care about the food served in prisons: people incarcerated in state prison return to our communities sooner than you might think. As we found in an analysis last year, the median time served in state prison is 16 months and the average is 29 months. That’s more than enough time for a poor diet to cause long-term health effects. Research shows just four weeks of eating an unhealthy, high-calorie diet can lead to long-term increases in cholesterol and body fat.

When people are released from prison, their health problems become community health problems — and a financial burden on the local public health system. Preventing and helping treat chronic illnesses by serving nutritious food is cheaper than medical treatment, both during incarceration and after release.

As the Washington report demonstrates, prison food has managed to get even worse over time — and more and more people have been forced to subsist on it as the prison populations have exploded. And now, states and communities must face the long-term health consequences — and resulting healthcare costs — of feeding large numbers of incarcerated people unhealthy food. Far from a frivolous complaint, unhealthy prison food is actually a public health concern likely costing states and taxpayers far more than it saves.

We explain what's next and what the families can expect on telephone justice.

by Peter Wagner,

February 8, 2017

On Monday, arguments were heard in a federal court case challenging the Federal Communications Commission’s regulations of the prison and jail telephone industry. A decision is not expected for several months, but there are a few updates to share nevertheless.

Centurylink, Global Tel*Link, Pay Tel, Securus Technologies, and Telmate sued the FCC when it started regulating the industry. Shortly thereafter, the Prison Policy Initiative joined with the D.C. Prisoners’ Legal Services Project, Citizens United for Rehabilitation of Errants (CURE), The Campaign for Prison Phone Justice, and the Office of Communication, Inc. of the United Church of Christ as intervenors in support of the government respondents in the case, and we were all represented by the Institute for Public Representation at the Georgetown University Law Center. By joining the case, we could help the FCC defend its orders, and ensure that the unique interests of the families and other stakeholders were represented in the case. The recent presidential election made our 2013 decision to intervene especially important.

The presidential election reshuffled the seats at the FCC. Ajit Pai, a commissioner since 2012 was made Chairman, and even though Pai had previously condemned the market failure caused by the corrupt commission system, he ultimately voted against the FCC’s regulations of the industry. And on January 31, the FCC told the Court that it was not going to defend two aspects of the regulations. Even as the FCC refused to support its own regulations, our attorney, Andrew Schwartzman, was able to defend the FCC’s work before the Court. We’re glad we intervened.

We don’t know what the Court is going to decide, and we don’t yet know how or whether Chairman Pai wants the FCC to address what he saw as “market failure” in the prison and jail telephone market.

All of this will become clearer over the next few months, but that leaves us with the immediate question of what families with loved ones behind bars can expect to pay. That too is complicated, in part because the Court stayed part of the FCC’s regulations.

Some states like Alabama have stricter regulations, and some prisons and jails have negotiated better deals for the families, but under the currently-enforceable federal rules:

- For both prisons and jails, inter-state calls will continue to be capped at a maximum of $0.21-$0.25/minute for debit/prepaid or collect, respectively. (These are the rate caps that went into effect in February 2014. For now, in-state calls are not subject to rate caps.)

In addition, the abusive hidden fees for both inter-state and in-state calls, which our report Please Deposit All of Your Money: Kickbacks, Rates, and Hidden Fees in the Jail Phone Industry found can easily double the price of a call, are now capped at:

- Payment by phone or website: $3 (previously up to $10)

- Payment via live operator: $5.95 (previously up to $10)

- Paper bills: $2 (previously up to $3.49)

- Markups and hidden fees embedded within Western Union and MoneyGram payments: $0 (previously up to $6.95)

- Markups and hidden profits on mandatory taxes and regulatory fees: $0 (We’ve seen these markups and hidden profits on “mandatory” taxes be 25% of the cost of the call)

- All other ancillary fees: $0. (There are many of these charges. Some of the most egregious ones are $10 fees for refunds, $2.50/month for “network infrastructure” and a 4% charge for “validation”.)

Later, if we are successful in Court and nothing else happens:

- In-state calls will be capped at $0.21-$0.25/minute, just like interstate calls. (This is particularly important because 92% of calls from prisons and jails are in-state, and because in the absence of regulation, jails are increasing the cost of these calls to up to an exploitative $1.50 a minute.

- The companies will be prohibited from defying the FCC’s rate caps by steering families to abusive “single call” products like Text2Connect™ and PayNow™ that charge $9.99-$14.99 for a single call.

Stay tuned.

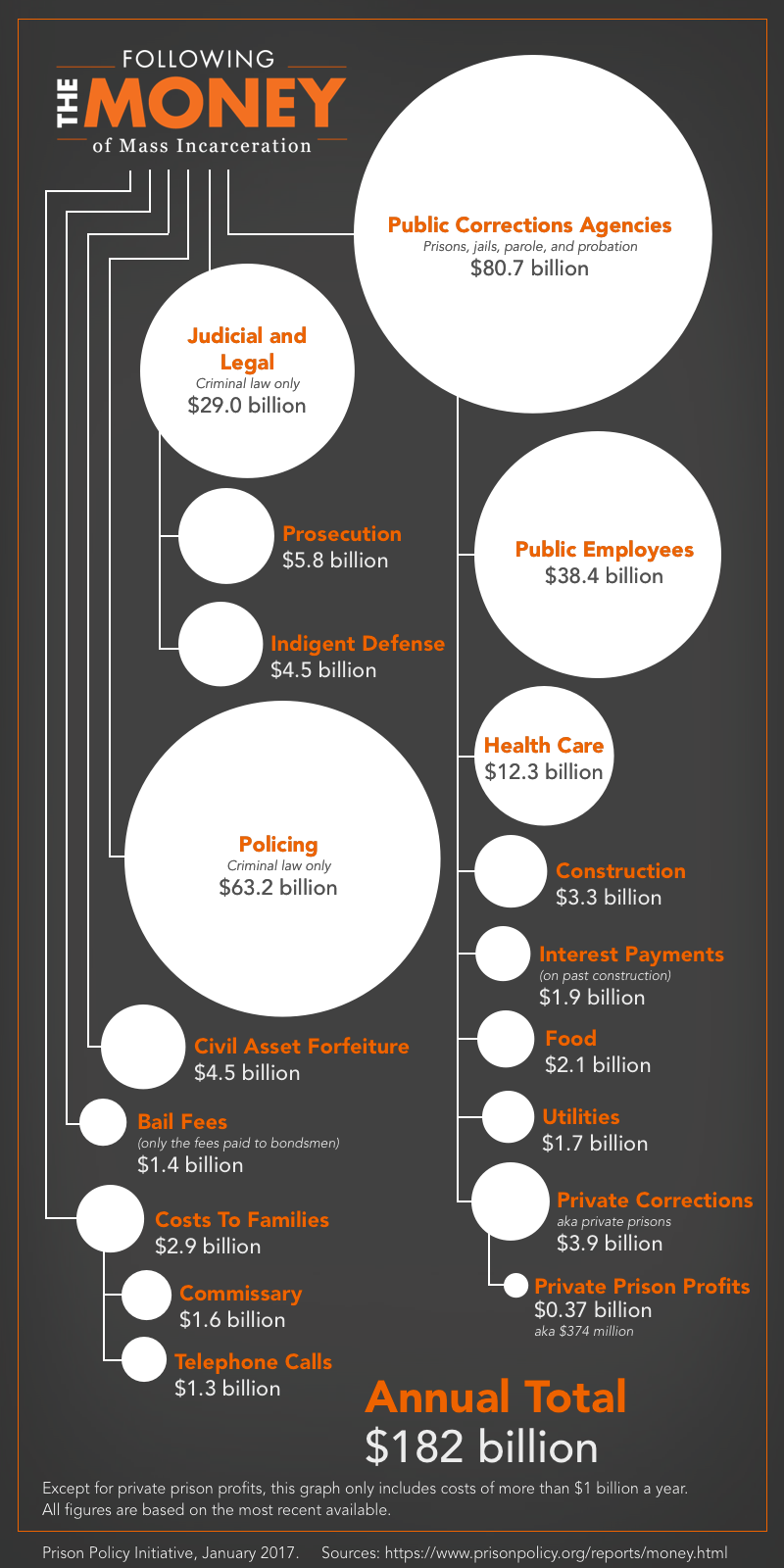

Our new report looks at the big picture to find that mass incarceration costs $182 billion per year; and we also calculate the cost of locking people up before trial.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

February 7, 2017

Our new report Following the Money of Mass Incarceration looks at the big picture and concludes that the government and families of justice-involved people spend $182 billion each year on mass incarceration and over-criminalization. But for this report we also calculate an important cost hidden within this figure: the cost of locking people up before trial.

This population which has recently grown to be the majority of people in jails, has not been convicted and is legally innocent. Some people were arrested a few hours or days ago and have not been brought before a judge, and others are too poor to afford money bail and must wait for trial.

On any given day, this country has 451,000 people behind bars who are being detained pretrial. In Following the Money of Mass Incarceration, we put a price tag on how much it costs local governments nationwide: $13.6 billion.

Jail policies matter. There are lots of strategies that individual jurisidictions can adopt to reduce their jail populations. Check out the MacArthur Foundation Safety and Justice Challenge to see community solutions aimed at reducing use of jails and high rates of pretrial detention. And for more on how the poverty of people detained pretrial makes money bail unaffordable and spurs pretrial detention, check out our 2016 report, Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates and endless cycle of poverty and jail time.

From state and federal legislation to the press, support for in-person visits continues to grow.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

February 1, 2017

In a January 2015 report, we discovered that 74% of jails that adopt video visitation go on to ban in-person visits. Fortunately, the movement to protect in-person visits from video technology has continued to grow. Here are some recent developments we wanted to share:

Welcome Lucius Couloute, our new Policy & Communications Associate!

by Wendy Sawyer,

January 31, 2017

Please welcome our new Policy & Communications Associate, Lucius Couloute.

Please welcome our new Policy & Communications Associate, Lucius Couloute.

Lucius is currently a doctoral student at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in the Sociology department; previously, he earned his Bachelor’s degree from UMass in Economics. His dissertation examines the role of race and insecure employment experiences during prisoner reentry. Lucius is from Hartford, where he also serves as a member of the Greater Hartford Reentry Council.

Welcome, Lucius!

In a first-of-its-kind report, the Prison Policy Initiative aggregates economic data to offer a big picture view of who pays for and who benefits from mass incarceration.

January 25, 2017

In a first-of-its-kind report, the Prison Policy Initiative aggregates economic data to offer a big picture view of who pays for and who benefits from mass incarceration.

The report, Following the Money of Mass Incarceration, and infographic are a first step toward better understanding who benefits from mass incarceration and who might be resistant to reform.

In the report, the Prison Policy Initiative:

- provides the significant costs of our globally unprecedented system of mass incarceration and over-criminalization,

- gives the relative importance of the various parts,

- highlights some of the under-discussed yet costly parts of the system, and then

- shares all of its sources so that journalists and advocates can build upon its work.

Following the Money of Mass Incarceration establishes that:

- Almost half of the money spent on running the correctional system goes to paying staff. This group is an influential lobby that sometimes prevents reform and whose influence is often protected even when prison populations drop.

- Private companies that supply goods to the prison commissary or provide telephone service for correctional facilities bring in almost as much money ($2.9 billion) as governments pay private companies ($3.9 billion) to operate private prisons.

- Commissary vendors that sell goods to incarcerated people — who rely largely on money sent by loved ones — is itself a large industry that brings in $1.6 billion a year.

“Following the Money of Mass Incarceration finds that mass incarceration and over-criminalization are deeply embedded in our economy,” said report co-author and Prison Policy Initiative Executive Director Peter Wagner. “Changing our nation’s criminal justice priorities is going to require challenging a lot of entrenched but often hidden interests.”

The report is available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/money.html.

The first ever national survey of in-state jail phone rates finds some jails charge more than $1.50 a minute.

by Aleks Kajstura,

January 19, 2017

Two recent submissions to the FCC shed new light on the high cost of in-state phone calls from jails. While the campaign to make phone calls from prison and jail more affordable for family and friends of incarcerated people has made significant progress, the new filings underscore how private companies continue to avoid regulation while charging unconscionable rates.

These submissions present new research which reveals that some in-state calls cost over $1.50 a minute, and finds pricing structures that “bear a remarkable similarity” to practices prohibited by the FCC.

In order to “highlight the current ICS [Inmate Calling Service] landscape” for the FCC, Lee Petro, counsel for the Wright Petitioners, and the Prison Policy Initiative (thanks to members of our Young Professionals Network) conducted a survey of jails served by the major ICS providers.

The most significant discovery made from reviewing the current pricing policies of the ICS providers was that several ICS providers have imposed a rate structure for intrastate ICS calls that bear a remarkable similarity to the now-prohibited “connection fee” which was prohibited in the 2015 Second Report and Order, and memorialized in Section 64.6080 of the Commission’s rules.

These pricing schemes have resulted in 15 minute calls that would cost $24.95 from the Arkansas County Jail via Securus and $17.77 from the Douglas County jail in Oregon via Global Tel*Link.

You can find the summary of the Comments submission findings in the Ex-Parte submission, and the rates for all of the jails surveyed in exhibits B and C of the Comments submission (starting on page 82), and exhibits A and D in an updated filing reflecting Legacy’s correction of their advertised rates.

Private companies amassing monopoly contracts, creating potential to rake in $172 million from friends and family sending money to incarcerated loved ones.

by Stephen Raher,

January 18, 2017

As with many areas of government, prisons and jails are increasingly shifting costs to those who can least afford it: incarcerated people and their families. In correctional facilities, this often takes the form of copays for medical care, forcing incarcerated people to purchase clothing or hygiene items, and cutting food service in favor of for-profit “canteens.” Because most incarcerated people lack money to cover such expenses, this means that family members must frequently transfer money to “inmate trust accounts.”

Historically, families could send money to an incarcerated relative’s account by simply mailing a money order. But private companies saw an opportunity to use these accounts as a potential source of profits. For an upcoming report, we set out to find the answer to a seemingly straightforward question: How much do these companies earn off of money transfers? It’s hard to say, because there is no publicly-available data that gives a complete picture; however, certain limited data can be used to arrive at a rough estimate.

Four states have published data on the volume of money transfers in their state prison systems. This data covers Nevada, Ohio, and Wyoming (all calendar year 2011), and Pennsylvania (2014). Dividing the total amount of transferred funds by the states’ respective prison populations yields average annual transfers of $737 per incarcerated person. Multiplying this average amount by the total population of all state prisons (in 2016) would yield annual transfers of $995 million.

But the amount of money transferred doesn’t tell us how much money the companies make on the process. The difficulty in estimating fee revenue comes from the fact that the amount of the transaction fee varies among jurisdictions. In addition, some jurisdictions may still allow family members to send funds for no fee through the mail; while other states may charge a fee for payments by mail, or simply prohibit no-fee options.

Direct evidence of fee revenue is available for JPay, Inc., one of the largest payment processors for prisons and jails. JPay is currently a subsidiary of telecommunications firm Securus Technologies, which is owned by private equity firm Abry Partners. In an April 2015 presentation to potential lenders, Securus stated that in 2014, JPay made $53 million in fees (page 49) on transfers of $525 million (page 38). This suggests an average fee of 10% (i.e., $53 million ÷ $525 million = .10).

If, as stated above, the total amount of state-prison money transfers is $995 million per year, then with fees at 10%, payment processors could potentially make up to $99 million in fees, assuming every prison system in the country privatized money transfer services and eliminated no-fee options. This aligns precisely with the Securus/JPay investor presentation, which estimates the total market for money transfers in state prisons to be worth $99.2 million in corporate revenue (page 45).

My discussion so far has not mentioned county jails and the federal prison system, because information about money transfers in these settings is even more difficult to find. In fact, some of the only information available at this time is Securus’s estimate of the total potential market. In 2015, Securus told potential investors that the total potential fee revenue from county jails and federal prisons was $58 million and $15 million respectively.

Notably, the most lucrative money transfer market may not even involve correctional facilities. Among the proliferation of user fees being imposed on the poor are fees levied on people serving time on probation or parole. Processing those payments means lots of money for companies like Securus/JPay. In fact, Securus believes that it if it obtained contracts for every state, federal, and local prison/jail in the country, it would be able to earn up to $172 million in fees. In contrast, the company believes that the total market for probation- and parole-related payments is worth nearly $300 million in fees.

Governments process hundreds of millions of dollars of payments every day. In the context of tax payments, court filings, license applications, and other types of user fees, agencies have created innovative no-cost options (including electronic payments) that facilitate quick, efficient transfers. But in the correctional setting, administrators have largely ignored these innovations, instead opting to outsource this function to private companies seeking to profit. As a result, money transfers are yet another way in which private companies profit off of families and friends seeking to support their incarcerated loved ones.

Money bail. Pretrial detention. Fines and fees. Race. Poverty. Vera connects the dots in a new report on user-funded justice in New Orleans.

by Wendy Sawyer,

January 10, 2017

Money bail. Pretrial detention. Fines and fees. Race. Poverty.

Vera connects those dots today in Past Due: Examining the Costs and Consequences of Charging for Justice in New Orleans. The report provides new evidence that there are few winners in a system that punishes defendants who can’t afford to pay bail, fines and fees — and then charges taxpayers for the cost of jailing them when they can’t pay.

Like many local and state criminal justice systems, New Orleans uses bail, fines, and fees to compel the “users” of the system to pay for some of the cost of policing, prosecuting, and jailing them. In theory, these costs are meant to enhance accountability; for example, money bail is intended to ensure appearance in court, when the defendant can get his or her money back. And the fees charged to defendants at sentencing — such as court costs or probation fees — are seen as cost saving measures for services brought on by defendants themselves.

But Vera’s report lays out the deep dysfunction of the system in New Orleans. Importantly, it gives us a clear picture of who is burdened most: black residents make up 59% of the population, but paid 84% of bail bond premiums and 69% of fines and fees. And in New Orleans, black households earn less than half what white households do. These racial and economic disparities should make a user-funded scheme seem like a bad idea from the outset. In practice, Past Due shows, it’s even worse.

First, Vera’s researchers tackled bail, which they found was a requirement for most booked defendants. As we have shown before, bail is set too high for many poor defendants to pay. In New Orleans, people were detained an extra 51 days on average because, even with bail amounts as low as $100, it was hard or impossible for them to pay. On any given day, nearly one-third of the New Orleans jail is occupied by people who are there simply because they can’t afford bail.

Besides those who can’t pay bail, New Orleans must also set aside a few beds in jail for those who can’t afford the fines and fees levied upon them at sentencing. Vera found that 536 people were arrested for non-payment of criminal fines and fees in 2015, almost all for municipal cases where the average amount imposed was just $228. People interviewed and surveyed by Vera were confounded by the expectation to pay court debts when their criminal justice involvement made their financial outlook bleaker than ever. As one person said, “I understand I gotta pay the money, but how can I pay the money if I’m a convicted felon and can’t get a job?”

While Past Due confirms much of what we know about the problems with bail, fines, and fees, its value to policymakers with an eye on the bottom line is the cost-benefit analysis it provides. Vera compared how much the city of New Orleans collected from bail, fines, and fees to how much it cost to jail people who could not afford to pay, and found that the city spent $1.9 million more than it brought in. This report makes clear that reforming the systems of bail and criminal justice fines and fees is not only a moral imperative, but also financially prudent.

The potential savings from reducing the jail population “pale[s]s in comparison to the potential to reduce the human toll of jail.” In a technical report accompanying Past Due, researchers estimated the taxpayer savings of $31 per day for every person kept out of jail — compare this with the $380 daily cost of jail borne by each incarcerated person, which accounts for the risk of violence, loss of liberty, lost wages, child care, and jail fees. This is to say nothing of the net effect on the families and communities of people who are jailed.

Vera’s report urges us to question user-funded systems that transfer millions from “historically disadvantaged black communities with the least money to spare” and then lock people up when they can’t pay.

President Obama's article speaks to some of the most important lessons we've learned in our work to end mass incarceration.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

January 10, 2017

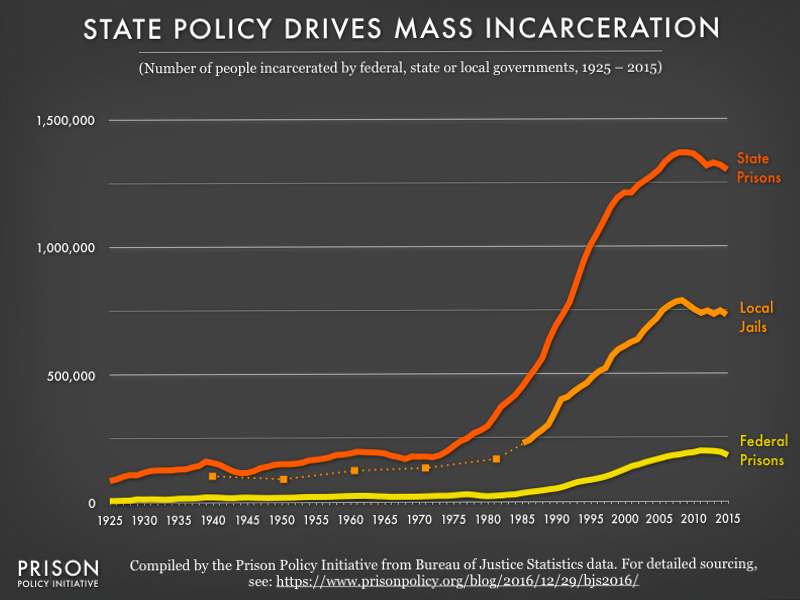

Last week, President Obama surprised criminal justice reformers with an article in the Harvard Law Review on The President’s Role in Advancing Criminal Justice Reform. While the President spends more of the article summarizing his efforts to reform the criminal justice system than sharing an analysis of the challenges he faced trying to make our criminal justice system more just, President Obama’s article speaks to some of the most important lessons we’ve learned in our work to end mass incarceration. We believe that understanding the following points is key to meaningful justice reform:

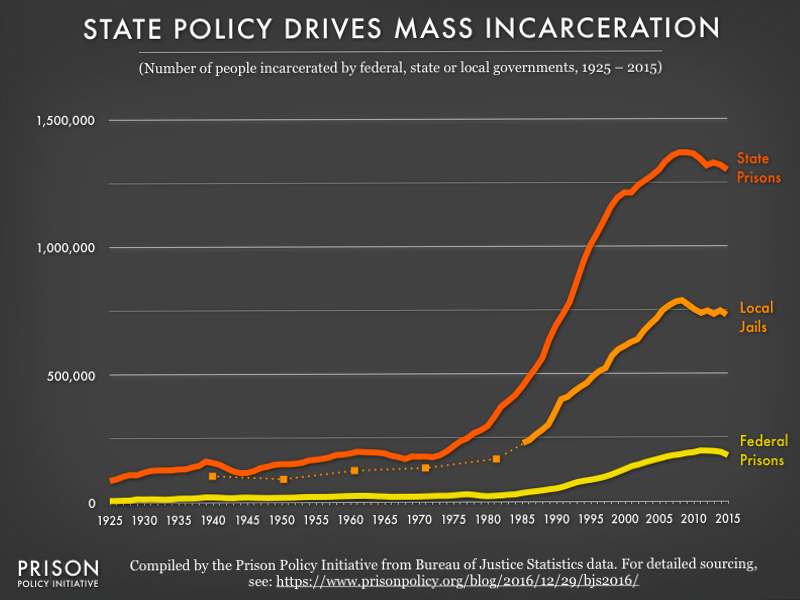

- State and local policies drive mass incarceration. Citing our report, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, Obama explains that, “State and local officials are responsible for most policing issues, and they are in charge of facilities that hold more than 90% of the prison population and the entire jail population.” President Obama’s reminder should spark hope among advocates. While criminal justice reform is likely to be more challenging at the federal level during the Trump administration, Americans should not forget how impactful state and local reforms can be in reducing the incarcerated population.

- Mass incarceration is bad for all Americans. President Obama reminds readers that “It would be a tragic mistake to treat criminal justice reform as an agenda limited to certain communities. All Americans have an interest in living in safe and vibrant neighborhoods…” The sheer scale of our criminal justice system means both that mass incarceration has harmed the lives of many Americans and that government resources that could be used for other social services are instead spent on locking people up. For these reasons, even Americans who have never come into contact with the criminal justice system or don’t have a loved one behind bars have an interest in the country reducing its unprecedented use of incarceration.

- The true reach of our criminal justice system goes beyond those behind bars. President Obama cites our blog to explain that beyond the incarcerated, there are the many Americans with criminal records, the people released from prisons each year, and the 11 million people who cycle through local jails. In our view, keeping the true scope of the system in mind will make it that much easier for advocates to steer clear of reforms that simply transfer people from one piece of the correctional control pie to another and think more expansively about what reducing incarceration rates means for correctional supervision like probation and parole.

President Obama’s article is further evidence of how far our country has moved away from the tough on crime narrative that used to be overwhelmingly popular with Democrats and Republicans alike. At this time when hateful rhetoric is becoming more normalized, we hope that more people can take a cue from Obama who speaks about those who have committed crimes as people who have made mistakes.

For more reactions to President Obama’s article, we recommend:

- Jonathan Blanks, Obama praises himself on criminal justice reform but he could have done so much more, Rare

This article points out that Obama fails to mention in his law review article how the federal government has responded to states’ growing liberalization of state marijuana laws and explains why that omission may have been intentional.

- Radley Balko, When Obama wouldn’t fight for science, The Washington Post

Radley Balko explains how the Department of Justice denounced a report by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology about forensic science and what the ramifications of the Department of Justice’s refusal to assess forensics might be.

- Mark Joseph Stern, The George W. Bush Advice Obama Should Have Taken, Slate

Slate published a new interview with Margaret Colgate Love, who served as United States pardon attorney from 1990 to 1997. Love explains that Obama could have had a more meaningful clemency legacy if he had used his pardon power more or created a clemency commission like President Ford.

This past fall, a new report from Prison Voice Washington detailed the decline in food quality served in the state’s correctional facilities. While incarcerated people often voice complaints about (very real) quality-of-life issues related to food service, there is a broader public health concern here: the long-term health consequences of forcing incarcerated people to consume unhealthy food.

This past fall, a new report from Prison Voice Washington detailed the decline in food quality served in the state’s correctional facilities. While incarcerated people often voice complaints about (very real) quality-of-life issues related to food service, there is a broader public health concern here: the long-term health consequences of forcing incarcerated people to consume unhealthy food. Food costs are also dwarfed by healthcare costs in prisons, so improving the nutritional quality of prison food would be a cost-effective way to improve inmate health. In our recent analysis of criminal justice costs, we found that correctional agencies spend almost six times more on health care than on food. Prison Voice Washington found that food costs make up less than 4% of the daily cost of incarcerating a prisoner — compared with healthcare, which accounts for 19% of the cost.

Food costs are also dwarfed by healthcare costs in prisons, so improving the nutritional quality of prison food would be a cost-effective way to improve inmate health. In our recent analysis of criminal justice costs, we found that correctional agencies spend almost six times more on health care than on food. Prison Voice Washington found that food costs make up less than 4% of the daily cost of incarcerating a prisoner — compared with healthcare, which accounts for 19% of the cost.

Please welcome our new Policy & Communications Associate, Lucius Couloute.

Please welcome our new Policy & Communications Associate, Lucius Couloute.