Prisons are a daily environmental injustice

On Earth Day, many people contemplate past and future demands for clean air, clean water, and protected landscapes. But society’s calls for a healthier environment rarely extend to incarcerated people, many of whom are confined in toxic detention facilities. We recap some aspects of how prisons leave both people and planet worse off.

by Leah Wang, April 20, 2022

No one is spared from reckoning with human-induced environmental change, like pollution from industrial emitters and increasingly severe natural disasters. Yet in correctional facilities, incarcerated people have no agency over almost any aspect of their lives, including their exposure to harmful and even potentially lethal conditions. Prisons fail to provide a basic standard of livability, while climate change and extreme weather test the ability of prison administrations to carry out contingency plans for the hundreds of thousands of people in their care. The ways in which environmental hazard and risk maps onto other unsafe conditions of confinement amounts to a human rights crisis that has persisted for decades.

Prisons are sited on uninhabitable, toxic wastelands

The rural geography of many of our nation’s prisons isn’t just unfortunate for those having to travel far from home to visit; prisons are too often built near (or directly on) abandoned industrial sites, places deemed fit only for dumping toxic materials. One-third (32%) of state and federal prisons are located within 3 miles of federal Superfund sites, the most serious contaminated places requiring extensive cleanup. Research warns against living, working, or going to school near Superfund sites, as this proximity is linked to lower life expectancy and a litany of terrible illnesses.

As a result of being on or near wastelands, prisons constantly expose those inside to serious environmental hazards, from tainted water to harmful air pollutants. These conditions manifest in health conditions and deaths that are unmistakably linked to those hazards.

In western Pennsylvania, for example, a state prison located on top of a coal waste deposit has done permanent damage, causing skin rashes, sores, cysts, gastrointestinal problems, and cancer, with symptoms often appearing soon after arrival. A scathing report from 2014 exposed these patterns of illness and neglect, but the prison — SCI Fayette — remains open.

And the devastating health outcomes at one prison in Louisiana was a smoking gun for environmental injustice — or a smoking tire, in this case. Laborde Correctional Center‘s neighbor, an abandoned tire landfill, caught fire and burned for four days before the prison decided to evacuate. The state’s environmental agency and the tire company are on the hook for failing to address compliance issues, but the damage had already been done to the health of the people trapped inside the prison’s walls.

Indeed, no region is more of a poster child for harmful prison siting than Appalachia, where new prisons have served as a failed economic replacement for the waning coal industry. For example, devastating mining and mountaintop removal activity in Kentucky has left residents — and now, many incarcerated people — with high rates of cancer and warnings against drinking or bathing in the tap water. With these day-to-day health hazards in mind, the promise of stable prison jobs and related economic development in Appalachia is hampered by its appalling environmental legacy.

This is not just a rural phenomenon. The Rikers jail complex in New York City is sited squarely on a landfill, making it a particularly cruel metaphor; the leaching of toxic fumes from poorly decomposing trash has caused anguish to the point where correctional officers have sued the city. It’s clear that those who set out to build these prisons care no more about the people inside than they do about garbage.

Bad water and bad air: Incarcerated people are forced to drink and breathe contaminants

Whether the result of terrible prison siting or run-down infrastructure, poor water quality plagues prisons nationwide, but little has been done. At one of the older state prisons in Massachusetts, incarcerated people fear for their health because their water has been “dark in color,” bad-smelling, and clogging filters with sediment for years. Testing showed dangerous levels of manganese, which can lead to neurological disorders. Meanwhile, a Texas facility was providing water with elevated levels of arsenic for ten years before the courts got involved, and an Arizona prison’s water, smelling foul and causing rashes, tested positive for a “petroleum product.” The list truly goes on and on, with a wide range of toxic substances swirling around the water supply of prisons.1

In addition to heavy metal and oil, water with unacceptable levels of bacteria has caused outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease — a potentially fatal type of pneumonia — at prisons in California, Illinois, New York and other states. Not only are prison administrations hesitant to replace the aging, corroded pipes that may have contributed to this horrendous bacterial growth, but staff enjoy free bottled water or bring in their own to avoid illness, leaving incarcerated people’s concerns largely unheard and unaddressed.

In the 1970s and 80s, the U.S. government took a firm stance against radon, an invisible, odorless gas known to cause lung cancer in indoor environments, launching an all-out eradication initiative in homes across the country. Yet in prisons, testing for and mitigation of radon has not been a priority. In 2018, a court found that a Connecticut prison was “knowingly and recklessly” exposing its incarcerated population to alarming levels of radon,2 in violation of the Constitutional right to an environment free from toxic substances.3 Incarcerated people have the right to clean air and water no less than anyone else, yet these and other basic necessities are routinely denied to them.

Over 1 million people are locked up in prisons, environments almost guaranteed to make them sick, while medical copays in many prisons only disincentivize treatment, making illness worse and in some cases more likely to spread.4 Often, correctional staff are also exposed to dangerous levels of pollutants, and concerns about health and safety are ignored by prison officials. This glaring cruelty of confinement makes it hard to believe that these “correctional” facilities make anyone better off.

Eleven miles of sewers: New prison and jail construction threatens human and environmental health

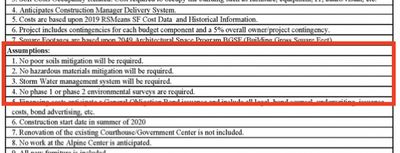

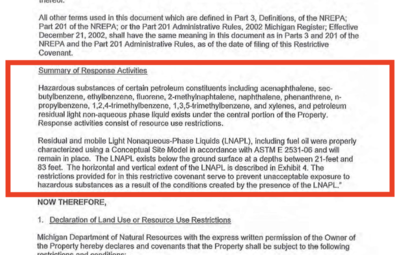

The plan to build a new jail in Otsego County, Michigan, would have been on an undeveloped site. According to a a public document from 2016 (top), the site had contaminated soils that would have required extensive clean-up before any digging and construction could take place. That fact was conveniently ignored by Otsego County public safety officials, who made an assumption of “no hazardous materials mitigation,” in their 2020 feasibility study (bottom) , creating the illusion of an environmentally and financially viable location.

Over the years, we’ve offered several reasons not to build or expand prisons and jails, but siting new correctional facilities brings up questions of ecological and health impacts. For example, when residents of Otsego County, Michigan voted against building a new county jail in late 2021, they prevented more than just a fiscally wasteful campaign to over-incarcerate people. The budget in the county and engineering firm’s feasibility study made an assumption that the site would require “no hazardous material mitigation,” even though government documents from four years prior declared the very same site to “contain hazardous substances,” in this case petroleum. Either the proposed “justice complex” would have required millions of dollars in soil remediation, or the damning document could have been rescinded or even ignored, allowing the county to do what too many other jurisdictions have done — knowingly incarcerate people on toxic land.

And next to Great Salt Lake in Utah, a massive new prison is under construction, despite great concern about its decidedly bad location and environmental impact. An engineering industry magazine even admitted it: The forthcoming Utah State Prison and its outbuildings, sited on a “remote wetland area” in a “sensitive environment,” is more like “a small city [of] 7,000 people,” more than half of those incarcerated. The city-sized project, requiring six miles of new roads and 11 miles of new sewer lines, is built upon soils that are known to “liquefy” when rattled by an earthquake (which would not be unusual, as this region sits upon on a network of geological fault lines). Plus, the new facility is located next to a closed, unregulated landfill; how long will it be before the untreated medical issues in Utah’s prisons are exacerbated by toxic landfill fumes?

Prisons refuse to respond to climate change-related emergencies

With their unwillingness to prepare for disasters due to global climate change, prisons (and other parts of the criminal legal system) stand to endanger or delay justice for people charged with a crime. For example, when Hurricane Harvey tore through the greater Houston area in Texas in 2017, several thousand incarcerated people were evacuated, but just as many were forced to wait out the storm in their facilities, with no plumbing and dwindling supplies. Not far away, Harvey caused flooding that put courtrooms out of commission and forced people detained pretrial to wait in jail longer for their day in court.

And in Louisiana, a state known both for its high incarceration rate and for its vulnerability to storms, hurricanes Katrina and Ida exposed serious shortcomings in disaster planning for its prison and jail populations. Trapped in dilapidated, flooding buildings and cut off from communication with loved ones, incarcerated people in Louisiana were simply left behind when evacuation was ordered for parish residents. In California, where wildfires are the primary environmental threat, evacuation plans are rare and unpracticed; the large populations in many prisons present a logistical nightmare — a disincentive to move incarcerated people out of harm’s way. In the words of Loyola University professor Andrea Armstrong, incarcerated people unwillingly stand “on the front lines of climate change.”

In many regions, scorching temperatures spurred on by global climate change are an active threat to incarcerated people with no access to relief. While the prevalence of air-conditioned homes in U.S. cities has skyrocketed, according to recent Census data, prisons have been slow or downright unwilling to respond to increasingly unbearable conditions, as we found in a 2019 investigation of the hottest parts of the country. Intolerably hot environments are worse for people on certain medications or with medical conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure, which incarcerated people tend to have at higher rates than the general population.

Experts have already warned that climate change will impact the criminal legal system in profound ways beyond adapting correctional facilities to a warming world. An entire generation of climate migrants, people forced to flee where they live due to extreme weather, may ironically become ensnared in the U.S. “crimmigration” system, finding themselves locked up and even more defenseless in the face of disaster. As the climate changes, so must prisons and other confinement facilities — and not in ways that expand the massive footprint of the criminal legal system.

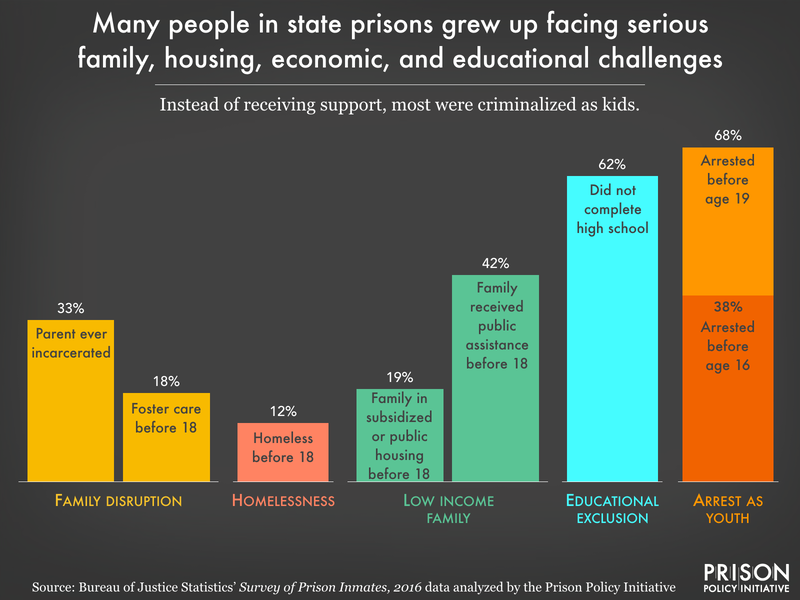

As research overwhelmingly shows, people in prison tend to come from disadvantaged, criminalized communities — the same communities bearing the burdens of environmental injustice. Moving people from the environmental hazards deliberately imposed where they live, to similar or more extreme hazards in prison through the criminal legal system, is an inane practice with enormous moral and fiscal costs. Decarceration efforts (like changing sentencing laws and accelerating compassionate release) will move people out of these death traps back into their home communities, where funding saved can be directed to where it should have gone all along.

Footnotes

-

Unfortunately, even when corrections officials do appear to take action on poor water quality, it’s likely to fall short of adequate. In a South Carolina jail, incarcerated people were in fact provided with bottled water after a chemical spill contaminated the municipal water supply. But they were given so little water — usually between two and three glasses per person per day — that the population was forced to bathe in and drink the “sweet-tasting,” chemically-tainted water. ↩

-

True relief still awaits incarcerated people (and correctional officers) suffering from radon exposure in Connecticut prisons, as litigation makes its way through the courts. ↩

-

Advocates often point to the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution to argue that prison conditions amount to “cruel and unusual punishment,” and numerous lawsuits have made the claim that exposure to environmental toxins fits the same criteria. In 1993, The Supreme Court helped expand the punishment concept to the risk of future harm and the failure of prison administrations to take measures to mitigate such harms, such as from secondhand smoke or asbestos. A lower court, upholding this landmark decision in 2005, insisted that “right to adequate and healthy ventilation” in confinement is clearly established. Despite these apparent wins, people in prison are still on the losing end: Because court cases can drag out for years, and because incarcerated people are systemically denied access to legal proceedings relating to their conditions of confinement, any finding of wrongdoing is too little, too late for many. In fact, the lawsuit at Garner Correctional Institute in Connecticut described here is still unresolved in the courts. ↩

-

Our roundup and supporting research have largely focused on prisons, but the 760,000 people locked up in local jails, youth and immigrant detention, and other such facilities brings the total confined population closer to 2 million people, and other confinement facilities are no less likely than prisons to be sited in places with similar environmental problems. ↩