Prisons and jails will separate millions of mothers from their children in 2022

58% of all women in U.S. prisons are mothers, and other important facts to know this Mother’s Day.

by Wendy Sawyer and Wanda Bertram, May 4, 2022

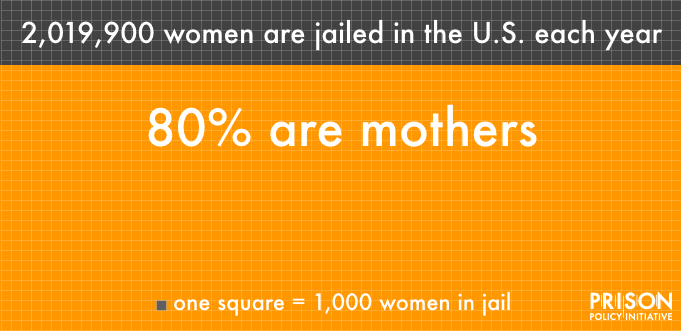

This Mother’s Day — as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to put people behind bars at risk — nearly 150,000 incarcerated mothers will spend the day apart from their children.1 Over half (58%) of all women in U.S. prisons are mothers, as are 80% of women in jails, including many who are incarcerated awaiting trial simply because they can’t afford bail.

Most of these women are incarcerated for drug and property offenses, often stemming from poverty and/or substance use disorders. Most are also the primary caretakers of their children, meaning that punishing them with incarceration tears their children away from a vital source of support. And these numbers don’t cover the many women preparing to become mothers while locked up this year: An estimated 58,000 people every year are pregnant when they enter local jails or prisons.2

150,000 mothers separated from their children this Mother’s Day is atrocious in and of itself – but that’s just one day. How many people in the U.S. have experienced separation from their mothers due to incarceration over the years? Unfortunately, these specific data are not collected, but we calculated some rough estimates based on other research to attempt to answer this question:3

- Roughly 570,000 women living in the U.S. had ever been separated from their minor children by a period of imprisonment as of 2010.

- An estimated 1.3 million people living in the U.S. had been separated from their mothers before their 18th birthdays due to their mothers’ imprisonment, also as of 2010.4

The scale of maternal incarceration – and its related harms – is monumental. But to be clear, these are estimates of how many children there were among the roughly 1 million women alive in 2010 who had ever been to prison, and only includes children who were minors when their mothers were in prison. These estimates are therefore very conservative, as they do not include the many, many more women who have ever been booked into a local jail.

Most incarcerated mothers are locked up in local jails

Women incarcerated in the U.S. are disproportionately in jails rather than prisons. As we’ve written before, even a short jail stay can be devastating, especially when it separates a mother from children who depend on her.

Estimates have been rounded for this graphic. Sources: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime Data Explorer (2019 table “Female Arrests by Age”) and Vera Institute of Justice, Overlooked: Women in Jails in an Era of Reform.

Estimates have been rounded for this graphic. Sources: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime Data Explorer (2019 table “Female Arrests by Age”) and Vera Institute of Justice, Overlooked: Women in Jails in an Era of Reform.

80% of the women who will go to jail this year are mothers — including 55,000 women who are pregnant when they are admitted. Beyond having to leave their children in someone else’s care, these women will be impacted by the brutal side effects of going to jail: Aggravation of mental health problems, a greater risk of suicide, and a much higher likelihood of ending up homeless or deprived of essential financial benefits.

How incarceration — and life after incarceration — hurts mothers and their children

Women who are pregnant when they are locked up have to contend with a healthcare system that frequently neglects and abuses patients. In a 50-state survey of state prison systems’ healthcare policies, we found that many states fail to meet even basic standards of care for expectant mothers, like providing screening and treatment for high-risk pregnancies. In local jails, where tens of thousands of pregnant women will spend time this year, healthcare is often even worse (across the board) than in state or federal prisons.

More challenges await incarcerated mothers and pregnant women when they are released from jail or prison. Formerly incarcerated women experience extremely high rates of food insecurity, according to a 2019 study. And as we previously reported, the 1.9 million women released from prisons and jails every year have high rates of poverty, unemployment, and homelessness, confirming what many advocates already knew: that there is a shortage of agencies and organizations able and willing to help formerly incarcerated women restart their lives.

It’s time we recognized that when we put women in jail, we inflict potentially irreparable damage to their families. Most women who are incarcerated would be better served though alternatives in their communities.

So would their kids. Keeping parents out of jail and prison is critical to protect children from the known harms of parental incarceration, including:

- Traumatic loss marked with feelings of social stigma and shame and trauma-related stress

- More mental health problems and elevated levels of anxiety, fear, loneliness, anger, and depression

- Less stability and greater likelihood of living with grandparents, family friends, or in foster care

- Difficulty meeting basic needs for families with a member in prison or jail

- Lower educational achievement, impaired teacher-student relationships, and more problems with behavior, attention deficits, speech and language, and learning disabilities

- Problems getting enough sleep and maintaining a healthy diet

- More mental and physical health problems later in life

Incarceration punishes more than just individuals; entire families suffer the effects long after a sentence ends. Mother’s Day reminds us again that people behind bars are not nameless “offenders,” but beloved family members and friends whose presence — and absence — matters.

Footnotes

-

Based on the most recent (2016) Survey of Prison Inmates, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) estimates 57,700 women in state and federal prisons are parents of minor children. We calculated approximately 55,142 mothers of minor children in local jails based on the Vera Institute of Justice report’s estimate that 80% of women in jail are mothers, and the BJS estimate of 110,500 women in local jails at mid-year 2019 (80% of 110,500 is 88,400). While jail populations dropped quite dramatically in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, we opted to use the more typical 2019 jail population for our estimate because other data sources show that jail populations have largely rebounded since mid-2020, but national 2021 data from BJS are not yet available. ↩

-

These estimates are based on the following percentages, reported in the linked sources: 4% of women admitted to state and federal prisons annually, and 3% of women admitted to local jails, are pregnant at the time of admission. The estimated 55,000 women admitted to jails while pregnant each year is based on the number of women over age 18 arrested in 2017 (over 1.7 million women), as reported in the original source. The estimated number of pregnant women admitted to state and federal prisons in a year is based on the total number of female admissions in 2019 (73,586) as reported by the Bureau of Justice Statistics CSAT — Prisoners tool (4% of 73,586 is 2,943.) While prison populations – especially admissions – dropped quite dramatically in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we chose to use the more typical 2019 prison data because other sources show that prison populations have since started to tick back up, but national 2021 data are not yet available. In contrast to the annual admission numbers, the share of women in prison who are pregnant on any given day (the “one-day prevalence” of pregnancy) was 0.6% in prisons and 3.5% in local jails as of the end of 2016. ↩

-

Both of these estimates are based on Shannon, et al.’ s estimates of the number of living U.S. residents who have been in prison at some point, as of 2010. We combine their findings with the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics about parents in prison and their children. But to do so, we have to make some assumptions – namely, that the percentage of women in prison who are mothers of minor children has remained more or less constant over the years, and that the average number of minor children per woman in prison has also remained constant over the years. To see how much these measures have changed over time, we reviewed Bureau of Justice Statistics reports about parents in prison and their children dating back to 1991, and found that between 1991 and 2016, the percentage of women prison who are mothers of minor children fell from 67% to 58% in state prisons and from 61% to 58% in federal prisons. At the same time, the average number of minor children per incarcerated mother has increased slightly from about 2.16 children in 1991 to 2.28 in 2016. These changes over time are not dramatic, but our resulting estimates should still be viewed as very rough estimates. ↩

-

Here’s the math behind our estimates: Shannon, et al. (2017) estimated 7,304,910 (or 3.11%) adults alive in the U.S. in 2010 had ever been in prison or on parole (whether still in prison or after release). They also estimated that 5.55% of the adult male population in 2010 had ever been in prison or on parole (they did not publish an estimated percentage of the adult female population that had been imprisoned). Based on Census data, we calculated an estimated 6,317,909 living adult males who had ever been in prison as of 2010 from that percentage. We then subtracted the number of adult males who had ever been in prison from the total number of adults who had ever been in prison; the difference – about 987,000 – is the number of adult women who had ever been in prison. Then, we took 57.7% of that total (0.577 * 987,000) to estimate that 569,500 (or roughly 570,000) of those women had been mothers of minor children while incarcerated (in 2016, 57.7% of women in prison had minor children). Finally, to estimate the number of people in 2010 who were minor children when their mothers were in prison, we multiplied the average number of minor children per woman with minor children in prison in 2016, 2.28 children, by our estimate of the number of women alive in 2010 who had been incarcerated when they had minor children (569,500) – 1,301,182 people. ↩