Racial disparities in diversion: A research roundup

Research shows diversion “works,” reducing harmful outcomes and increasing access to social services. However, studies also suggest diversion is routinely denied to people of color, sending them deeper into the criminal legal system. We review the research and remind practitioners that most diversion programs aren’t designed around racial equity — but should be.

by Leah Wang, March 7, 2023

As the costs and impacts of mass incarceration continue to grow, along with increased public outrage on the issue, counties and municipalities are adopting a wide range of programs that divert people out of the criminal legal system before they can be convicted or incarcerated. Diversion programs exist to move people away from overburdened court dockets and overcrowded jails, while offering to connect them with treatment, and saving money in the process.1 This practice sounds like a win-win for communities — and it’s successful by many metrics — but as we explain in our 2021 report about diversion programs, their design and implementation greatly impact the outcomes for defendants. That report focuses on the stage of the criminal legal process at which diversion occurs, with the earliest diversions (i.e., pre-arrest) offering the most benefits.

This briefing builds on our previous work by examining how — like every other part of the criminal legal system — diversion programs are often structured in ways that perpetuate racial disparities. Here, we review key studies showing how people of color who are facing criminal legal system involvement are systematically denied or excluded from diversion opportunities. This inequity has a ripple effect, contributing to the troubling racial disparities we see elsewhere, in pretrial detention, sentencing, and post-release issues like homelessness and unemployment. We conclude that policymakers and practitioners involved in diversion programming must address the cost, eligibility requirements, and discretionary decision-making to offer these vital opportunities in a racially equitable way.

Please note that because existing research is largely centered around prosecutor-led diversion programs, this briefing and its recommendations are, too.2 Prosecutors hold immense power in their decisions to file or dismiss charges, release pretrial defendants, and recommend sentences; in this way prosecutors are arbiters of racial fairness in the criminal legal system, in part through diversion.

Cost: “Pay-to-play” diversion programs leave low-income Black and Hispanic people unable to participate

More often than not, diversion levies exorbitant fees on its participants. Indeed, many prosecutor-led diversion programs are funded by users (i.e., participants) themselves, creating a two-tiered system where those who can pay will receive the benefits of diversion. Desperate for an option that avoids prison time, others may enroll in diversion only to be kicked out when they can’t afford fees for participation, treatment, drug testing, or something else.

Across the country, prosecutors’ offices have pitched user-funded diversion as a virtuous and fiscally responsible approach to reducing mass incarceration.3 But the indisputable relationship between income, race, and ethnicity means that fee-based diversion remains out of reach for people of color, the same way that bail and other fines and fees disproportionately burden Black and Hispanic people.

A groundbreaking report from the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice highlights the bleak financial landscape of diversion. Their survey of nearly 1,000 people involved in diversion programs in Alabama revealed that low-income people resort to extreme measures to pay their fees: The majority of respondents (82%) gave up one or more basic necessities like rent, medical bills, or car payments in order to pay various fees. Unsurprisingly, more than half of a subset of survey-takers (55%) made less than $15,000 per year, and 70% had been found indigent. Despite this high level of need, only 10% were ever offered a reduced fee or a fee waiver for a diversion program.

Even though that survey’s respondents were about equally white (45%) and Black (47%) and the survey responses were not broken out by race, the report’s authors assert that the Black-white wealth gap in Alabama “could be a major reason” that Black Alabamians are disproportionately excluded from diversion opportunities.

Fee waivers are clearly the exception, rather than the rule: In 2016, The New York Times reviewed diversion guidelines issued by 13 of South Carolina’s 16 state prosecutors, and found that only two documents mentioned the possibility of a fee waiver for indigent people. When we know so much about how poverty is criminalized and racialized, diversion programs designed this way seem particularly cruel.

Eligibility: Diversion programs have narrow eligibility criteria, excluding people with prior “system” contact — who are disproportionately people of color

In a world where not every individual can be diverted, someone must decide who (or what type of charge) is eligible for diversion. The “seemingly neutral constraints” on diversion programs often prioritize people with little to no criminal history, with often arbitrary rules. Criminal history is also built into risk assessment tools, which quantitatively express a person’s public safety or “flight” risk.4 These tools are favored by courts nationwide because they appear accurate and objective, when in fact they’re built on racially-biased data.

Right away, these eligibility criteria disproportionately exclude Black people, who are arrested as youth, stopped by police generally, and jailed and imprisoned at higher rates than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States. For example, a recent study found that a Jacksonville, Fla. diversion program required a third degree, “nonviolent” felony charge and no more than one prior conviction for a “nonviolent” misdemeanor: In other words, a random and nearly impossible standard to meet. Unsurprisingly, only 16% of Black felony defendants were eligible for this program, compared to 23% of white and 28% of Hispanic defendants. Rules that unnecessarily limit diversion to “first-timers” only serve to keep criminalized, marginalized groups trapped in the carceral system.

Another vexing but all-too-common feature of post-filing5 prosecutor-led diversion programs is that they often require a guilty plea in order to participate. In pleading guilty, an individual signs away their right to any further due process, and faces immediate sentencing if they’re terminated from their diversion program. While these “post-plea” diversions (also called deferred adjudications) may be convenient for a prosecutor, who wouldn’t have to take further action on that person’s case, it’s unjust to force someone into this high-stakes situation just to receive social services.

Research also finds that some diversion programs require that participants have a specific family structure at home. According to the Sentencing Project, Black youth are more likely to live in single-parent, multi-generational, or blended households that do not meet these criteria, leading to a baseless finding of ineligibility. A 2018 study found that a youth’s family structure had no effect on whether or not they completed diversion; neither did race. Youth diversion programs also often require an admission of guilt, as explained above; research illustrates that Black and Native youth, likely due to greater mistrust of the criminal legal system, are less likely than white youth to admit guilt. This reality keeps youth of color from accessing diversion, which hurts their future prospects through the mark of a juvenile adjudication.

But eligibility is not always enough: A 2021 multi-site study found that in Tampa, Fla., qualified white defendants were more likely (29%) to be diverted to their drug pretrial diversion program, compared to qualified Black (22%) or Hispanic (18%) defendants. In Chicago and Milwaukee, racial and ethnic disparities in felony diversion rates were large, too, favoring white defendants; updated data from Chicago show that the disparity is shrinking, but still present.6

Discretion: Prosecutors decide who they think is capable or worthy of diversion; biases can leave racial minorities behind

Diversion decisions are often highly subjective, leaving candidates vulnerable to the racial biases held by police, prosecutors, judges, or other decisionmakers. Even when an individual qualifies based on their charge, criminal record, or need for treatment, they must ultimately be offered diversion. Unfortunately, research has shown that prosecutors offer diversion to Black defendants much less often than white defendants with similar legal circumstances.

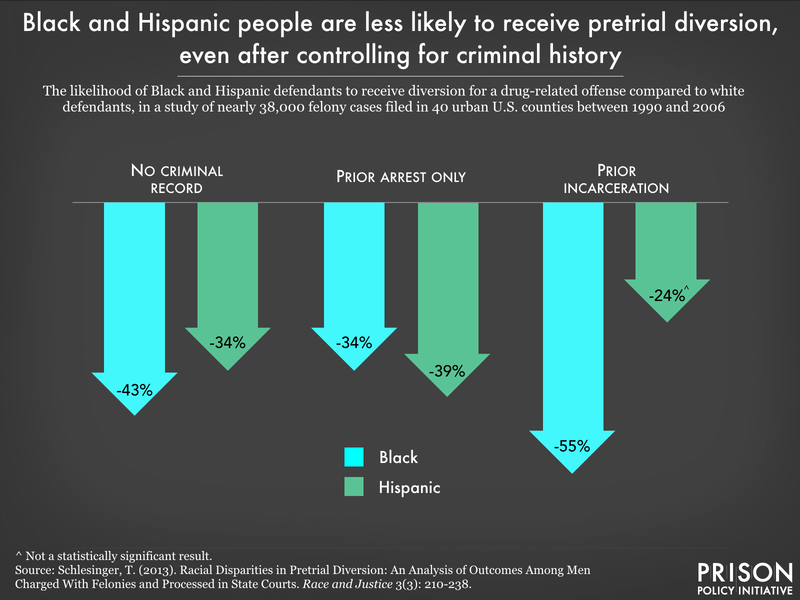

A 2013 study found that Black, Hispanic, Asian and Native American (the last two grouped as “Other race”) male defendants were always less likely to receive pretrial diversion compared to similarly situated white defendants in 40 large jurisdictions in the U.S. The study’s author found that additional charges, or more than one felony charge, lowered the odds of pretrial diversion by as much as 35 percent. Since prosecutors tend to bring more charges, and more punitive plea offers, against Black and/or Hispanic defendants, factoring in the number of charges can hardly be considered racially neutral.

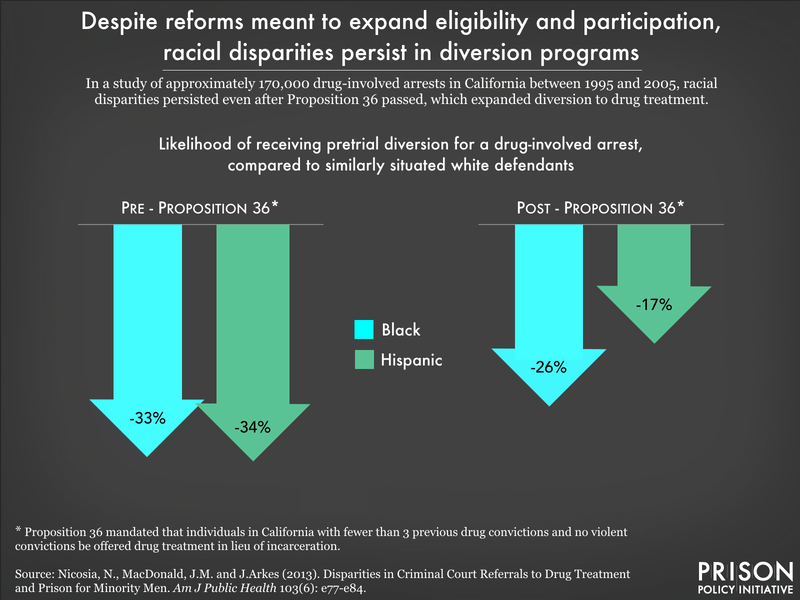

Similarly, in 2014, a group of researchers looked at people diverted to drug treatment in California, finding that differences in how Black and white people were diverted could not be explained by case-level details or by the state’s law implementing mandatory diversion for eligible drug offenses. In the end, they concluded that “diversion to treatment appears to be driven by the discretion of court officials” rather than any other factor.

Sadly, evidence also points to discretion working against Black youth and their families when it comes to diversion. A 2013 review of racial and juvenile justice mentions dangerous stereotyping of Black parents “unwilling to control” or supervise their child, leading to a subjective decision of ineligibility for diversion.

It’s difficult to pin down whether cost, eligibility, discretion, or some other mechanism is the most insidious when it comes to racial disparities in diversion. They all appear to burden Black families the most, even when accounting for other factors.

Diversion programs can address racial disparities by increasing access and eliminating collateral consequences

The research is clear: Diversion alone isn’t enough to address the harms of racialized mass criminalization. Left to their own devices, people who design diversion programs and policies have built in restrictions and subjectivity that disproportionately thwart people of color, forcing them further down the road to incarceration. Existing or proposed programs must take steps to ensure that post-arrest diversion programs are equitable and accessible by all, particularly communities that are overrepresented in the criminal legal system. These steps include (but are not limited to):

- Vastly expanding eligibility criteria to address the reality that Black and Hispanic people have more frequent contact with police, jails, and courtrooms that can lead to exclusion from diversion programs. With so many more qualified participants, prosecutors or other decisionmakers may rely less on discretion and more on presumptive eligibility to move people off overwhelmed court dockets (or prevent them from formal “system” involvement in the first place).

- Making diversion financially accessible to all participants, especially low-income people who may resort to extreme measures in order to stay in compliance. The status quo of user-funded diversion is out of touch with its purported goal of keeping people on pathways to health and success in their communities. Fee waivers should be automatic for those who have already shown indigency.

- Mitigating collateral consequences of a conviction. The requirement to plead guilty in order to participate in diversion is illogical and overly burdens defendants of color who, once they have a conviction record, are likely to struggle finding employment, housing, or a future diversion opportunity. People who successfully complete diversion should have any relevant records expunged, preventing collateral consequences. Practices like leaving charges pending during a program or simply dismissing charges at the end often isn’t enough, as that activity may still appear in a background check.

Finally, research specifically about how race or ethnicity impact access to, or success with, diversion programs remains somewhat sparse.7 Individual program evaluations often show that diversion “works” and is cost-effective, but they typically don’t consider race or ethnicity, cost to participants, or apples-to-apples comparisons to other programs. Data collection on racial and ethnic groups in diversion must extend beyond Black and Hispanic groups, and should also include sex and gender identity. Failure to acknowledge and address inequities can exacerbate existing racial divides — saving the harshest aspects of the system for people of color while providing easier pathways for white people entangled in the criminal legal system.

Ultimately, leaders should keep in mind that even if these pretrial diversion programs are administered perfectly, they still come with a host of collateral consequences that can last for years or the rest of their lives. The best diversion programs are actually investments in social services and non-law enforcement responses to community needs, keeping people out of the criminal legal system entirely. These investments prioritize community well-being and public safety over punishment and can reduce the footprint of mass criminalization in America.

Footnotes

-

For an explanation of different types of diversion programs, see our comprehensive report, Building exits off the highway to mass incarceration. ↩

-

It’s also worth mentioning that we include diversion research in both adult and youth populations, even though our diversion report assumed an adult’s experience. Diversion actually originated in the juvenile justice system, and academic research has remained focused on outcomes of youth diversion programs. ↩

-

Not all fee-based diversion programs make headlines, but a marijuana diversion program in Arizona faced scrutiny in 2018 when advocates discovered that Maricopa county and its attorney raked in $2 million annually from the program, which is available to those who can afford the $1,000 fee. And a quick Google search for “program diversion fees” leads to similarly harsh fee structures, like a Broome County, N.Y. traffic diversion program charging $200 or $400 per ticket, or this Lee County, Ala. program extracting a $100 application fee, plus administrative fees ranging from $10 to $1,000 depending on the offense. ↩

-

Risk assessment tools are often mentioned with respect to pretrial decision-making, when a judge must determine if someone in jail should remain there with or without bail, or be allowed to await trial at home. However, risk assessments are frequently used in other parts of the criminal legal system, like in diversion, in correctional institutions, and for reentry and supervision purposes, with similar frameworks. ↩

-

Prosecutor-led diversion can occur at one of two stages in the evolution of a criminal case: pre-filing, or before the prosecutor files formal charges, or post-filing, after the court process has begun but before a final case disposition. Completion of post-filing diversion program leads to the initial charges being dismissed without a trial. But while charges are pending, or even after they’re dismissed, they can show up in a background check, harming employment, housing, and other prospects. ↩

-

According to analysis from Prosecutorial Performance Indicators (see “PPI 7.5, Diversion Differences by Defendant Race/Ethnicity”), the diversion rate for Black felony defendants in Cook County, Ill. (Chicago) was over 15 percentage points lower than the diversion rate for white felony defendants; in the first few months of 2020, this difference hovered around 6 percent. ↩

-

This may be because diversion programs are “local creations,” formulated by agencies and offices with their own rules and measures of success, making them hard to analyze and compare. ↩

I was disgusted but unsurprised by the description of fees being levied on diversion programmes. Here in the UK, so far as I am aware and including my personal experience, no such programmes charge any fees to the users. Of course, the very basis of American culture is ‘personal responsibility’, most rigidly for the working class and the poor, so it would be strange were US diversion programmes free at the point of delivery. From the perspective of the UK, the request to make diversion financially accessible to all participants looks far too small. Why not have no user fees for anyone? Indeed, further: here, such programmes provide travel costs as well, ensuring that no-one has an excuse for not attending.

For people who have mental health, learning disability, substance misuse or other vulnerabilities when they first come into contact with the criminal justice system, the National Health Service is piloting its own Liaison and Diversion programme. Again, this is free of charge.

I first became aware of the absurd injustice of charging people for their own diversion in the 2007 film Disturbia, in which the character played by Shia LeBeouf is a teenager whose mother is forced to pay a substantial monthly rental for the electronic tag her son must wear. That would not be the case here in the UK.