New research links medical copays to reduced healthcare access in prisons

Using our prior research on prison wages and medical copays, researchers found that higher copays obstruct access to necessary healthcare behind bars, even as prison populations face increasing rates of physical and mental health conditions.

by Emily Widra, August 29, 2024

In most states, people incarcerated in prisons must pay medical copays1 and fees for physician visits, medications, dental treatment, and other health services. While these copays may be as little as two or five dollars, they still represent massive barriers to healthcare. This is because incarcerated people are disproportionately poor to start with, and those who work typically earn less than a dollar an hour and many don’t work at all. A new report by Dr. Emily Lupez et. al, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, builds on our analyses of prison copay and wage policies across all state prison systems and the findings are clear: medical copays in prisons are associated with worse access to healthcare behind bars. These unaffordable fees are particularly devastating because they deter necessary care among an incarcerated population that faces many medical conditions — often at higher rates than national averages — and routinely faces inadequate health services behind bars.

In their recent publication, Dr. Lupez and her fellow researchers analyzed nationally representative data from state and federal prison populations published in the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016.2 While we previously published our own analysis of the same dataset in 2021, this new research goes further by analyzing changes from the 2004 data and mapping our copays and wages data onto health data from people in prison. The researchers compared the 2004 and 2016 iterations of the Survey and found that, overall, people in prison are facing more chronic physical and mental health conditions than they were in 2004.

Additionally, Dr. Lupez and her colleagues measured the effect of prison medical copays on access to specific healthcare services (including pregnancy-related care), access to clinicians for people with chronic physical conditions, and the continuation of medications for mental health. For each state,3 they used our 2017 copay and wage data to categorize each survey participant into one of three categories: no copays, copay amounts less than or equal to one week’s prison wage, and copay amounts greater than one week’s prison wage.4 Their results provide further evidence that medical copays limit access to care among the most vulnerable people in the system.

Many people in prison do not receive even the most basic, necessary healthcare

We already know that prison healthcare regularly falls short of the constitutional duty to care for those in custody. While most people in state prison report having seen a healthcare provider at least once since admission, nearly 1 in 5 have gone without a single health-related visit since entering state prison. Accordingly, the authors first examined general access to healthcare among three groups of people in state and federal prisons: people who were pregnant when admitted to prison, people with chronic physical conditions, and people with mental health conditions. They found that even the most basic care — like obstetric exams for pregnant people or any visit with a healthcare provider for people with chronic conditions — is not provided to surprisingly large portions of the affected population.

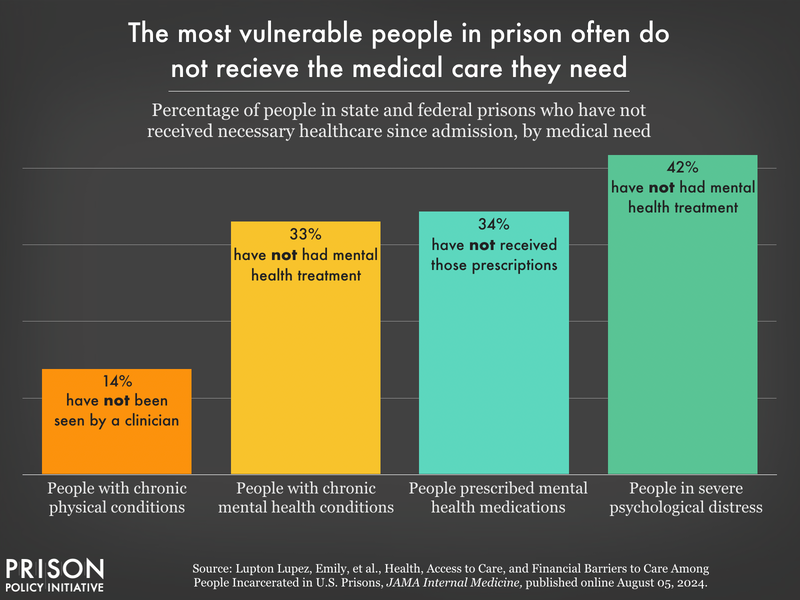

Treatment for chronic physical conditions. More than 1 in 10 people (14%) with at least one chronic condition in state and federal prisons had not been seen by a clinician since they were incarcerated. Within their first year of imprisonment, more than a fifth of people with chronic conditions (22%) had not yet been seen by a healthcare provider. Chronic diseases — by definition — require ongoing medical attention, and for the 62% people in state and federal prisons5 who have them, the lack of consistent, adequate medical treatment can have disastrous and fatal consequences.

Mental healthcare. Among the almost 400,000 people in state and federal prisons with chronic mental health conditions,6 one third (33%) had not received any clinical mental health treatment since entering prison. Again, those who were within their first year of incarceration were even more likely to report no treatment: 39% had not yet received any mental health treatment compared to 29% of people incarcerated for more than one year. Similarly, more than 41% of people experiencing severe psychological distress7 in state and federal prisons had not received mental health treatment.8 And more than one third (34%) of people who had been taking prescription medication for a mental health condition at the time of their offense had not received their medication since entering prison.9

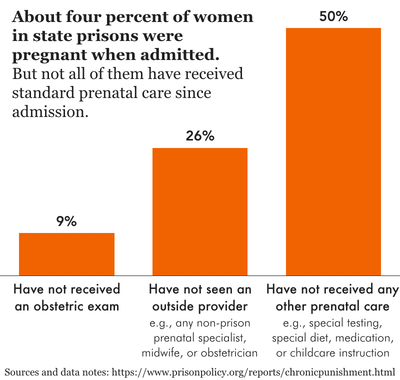

Pregnancy-related healthcare. Standard prenatal healthcare for pregnant people involves monthly doctor’s appointments at minimum, as well as screenings, tests, vaccinations, and patient education usually conducted by a perinatal specialist. But a shocking proportion of pregnant people in state prisons did not receive so much as an obstetric examination (9%), see any outside providers or specialists (26%), or any pregnancy-education from a healthcare provider (50%) after entering prison.

Medical copays and fees block access to necessary healthcare

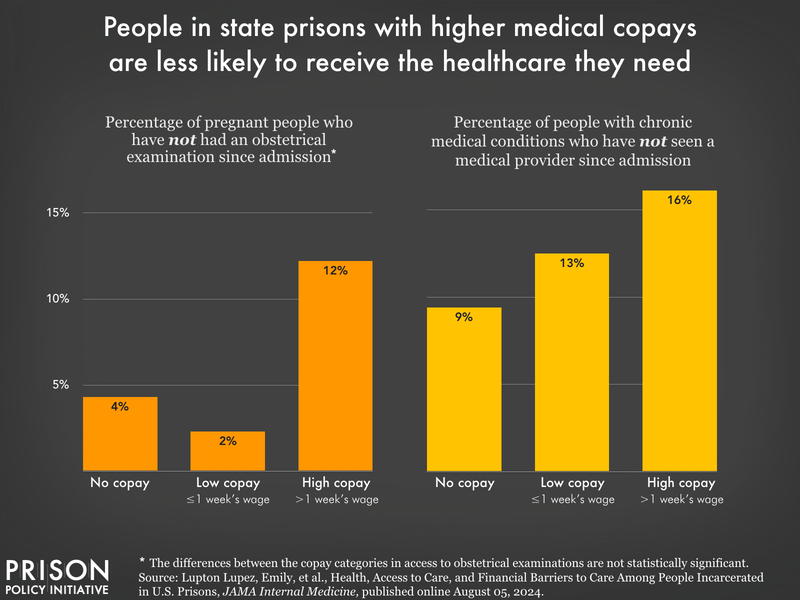

When healthcare needs come up against an arduous and expensive sick call process, people are forced to jump through arbitrary hoops just to see a doctor — or delay or forgo medical care altogether — as their health deteriorates. The researchers found that prison systems with more expensive medical copays (relative to prison wages) limit access to necessary healthcare for incarcerated pregnant people and those with chronic conditions more than prisons with no copays or copays equivalent to or less than one week’s prison wage.

Healthcare in prisons is subpar for almost any medical condition, and chronic physical conditions are often more prevalent behind bars than in the general population. The researchers found that medical copays clearly impact access to healthcare for the more than 500,000 people incarcerated in state and federal prisons who have conditions like heart disease, asthma, kidney disease, and hepatitis C. This is particularly alarming considering many of these conditions require regular medical management or can even be cured.

People with chronic conditions in state prisons where copays exceed a week’s wage are less likely to have seen a healthcare clinician while incarcerated than those in prisons that charge no copays or lower copay amounts. Among people with chronic physical conditions who have been incarcerated for more than one year, 12% of incarcerated people who face more unaffordable copays have not seen a clinician. Meanwhile, in prisons with relatively lower copays or no copays, less than 8% of people with chronic physical conditions have not yet seen a clinician after being incarcerated for more than one year.

Similarly, pregnant people in state prisons do not receive standard prenatal care and medical copays make this situation worse. Pregnant people in state prisons without medical copays or with lower copays relative to their wages were more likely to have received an obstetrical examination and clinical pregnancy education than those in prisons with copay amounts more than a week’s prison wage.10

Copay waivers and exemptions. Researchers also identified prison policies granting copay exemptions for some healthcare services for some people: at least 25 state departments of corrections and the federal prison system have copay waivers for chronic conditions, while 13 states have waivers for pregnancy-related care. However, as correctional health expert Dr. Homer Venters explains: “many chronic care problems aren’t detected when a person arrives [at the jail or prison], so to get treatment… requires the sick call process… Many systems have a practice of requiring two or three nursing sick call encounters before a person sees a doctor.”11 In other words, someone who meets the exemption criteria likely will still need to pay copays for the initial two or three nursing sick call visits before clinicians identify them as someone who should be exempt from copays.

It’s worth noting that the researchers repeated their analysis of how copays impact access to healthcare services among people without any reported chronic conditions in state prisons. If the chronic care waivers were working as intended, they reasoned, people who do not have chronic conditions would experience even lower rates of healthcare access compared to people with chronic conditions who have their copays waived. Instead, they found people who do not have chronic conditions appear to face similar rates of healthcare access as those who do, suggesting that these waivers are not routinely and consistently applied in a way that actually promotes healthcare access for the most vulnerable people in prison.

From 2004 to 2016, rates of chronic illness and mental illness increased in state and federal prisons

In addition to finding that higher copays restrict healthcare access, the researchers delved into demographic and health-related changes among the prison population between 2004 and 2016.

Demographics. People in prison in 2016 were more likely to be older; identify as Hispanic, multiracial, or some race other than white or Black;12 and to have been incarcerated multiple times compared to those incarcerated in 2004. These are groups of people that already face significant barriers to healthcare and often have poor health outcomes, even outside of prison. Older adults are more likely to have more medical conditions, which are already more prevalent behind bars. Outside of prison, Hispanic adults report less access to regular medical care and higher rates of uninsurance, while Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native people are less likely to receive necessary mental healthcare and have faced larger declines in life expectancy than their white counterparts. Ultimately, multiple periods of incarceration can negatively affect health status, and experiencing years of limited resources, inaccessibility, and understaffing in prison healthcare creates a situation in which each year spent in prison takes two years off of an individual’s life expectancy.

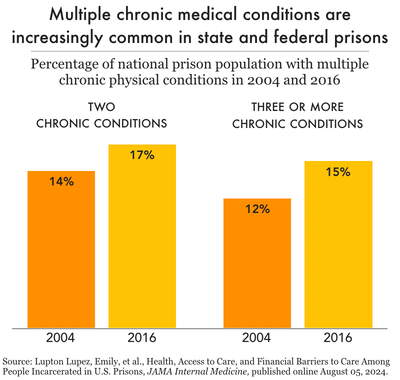

Chronic physical conditions. As we discussed in our 2021 report, Chronic Punishment: The unmet health needs of people in state prisons, chronic physical conditions and infectious diseases are more prevalent in prisons than among the nation at large. This newest analysis from Dr. Lupez and her colleagues reveals that these chronic conditions are more common in state and federal prisons than they were in 2004. For example, the percentage of the prison population facing at least one chronic condition increased from 56% in 2004 to 62% in 2016, and the percentage facing three or more chronic conditions increased from 12% to 15%. In other words, a larger portion of the prison population is facing chronic illness, and in many cases multiple chronic illnesses.

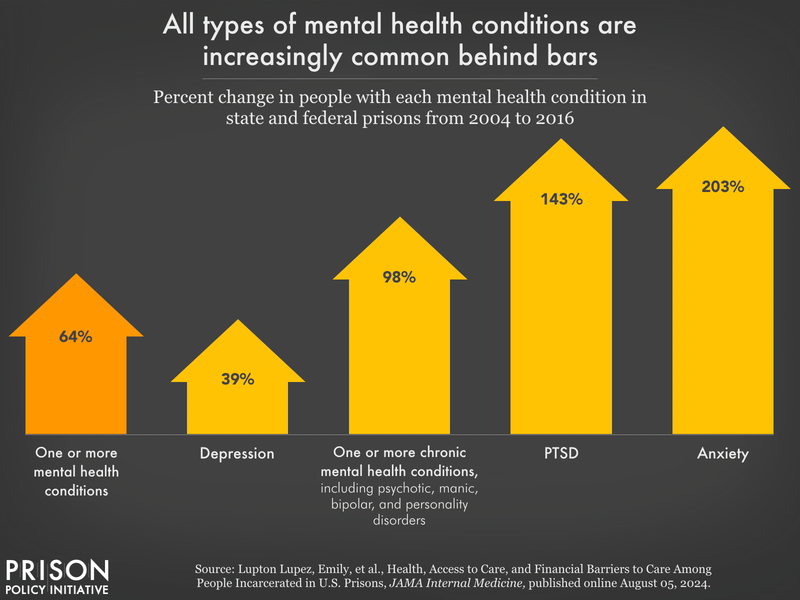

Mental health conditions. The researchers also found that mental health conditions were more common in 2016 than in 2004. The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey offers data on the proportion of the state and federal prison population who have ever had depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders, manic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and personality disorders. The prevalence of every one of these conditions increased in the prison population between 2004 and 2016: in 2004, nearly a quarter of the prison population reported one mental health condition and by 2016, this had increased to more than 40% of people in prison.13 Not only are mental health conditions more common, but more people are facing chronic mental health conditions in particular: the proportion of people in prison with chronic mental health conditions practically doubled from 2004 to 2016 (14% to 27%).

This study ultimately underscores the urgency of ending medical copays and healthcare fees in prisons and jails, and provides evidence that unaffordable copays put necessary medical care out of reach for far too many incarcerated people. Generally speaking, this study shows that incarcerated people are sicker than ever, the healthcare options available to them are grossly inadequate, and people are not getting the constitutionally-guaranteed care that they need — regardless of whether prisons charge copays or not.

As a final note, we are gratified whenever our work is repurposed by other researchers like this — it’s why we publish our detailed appendix tables and other data collections, many of which can be found in our Data Toolbox. If you are a researcher using our data, we encourage you to reach out with any questions and to let us know how you are using our work.

Footnotes

-

Unlike non-incarcerated people, people in prison do not have a choice about their medical coverage, nor how “cost sharing” applies to them. There is no “insurance” system that covers them, so the term “copay” is a misnomer for the fee they are charged to request a medical appointment or to obtain a prescription. As the organization Voice of the Experienced argues, the use of this term legitimizes these unaffordable fees, which deter people from seeking needed medical care. They suggest more descriptive terms such as “medical request fees” or “sick call fees.” ↩

-

The most recent iteration of the Survey was administered in 2016 and the data were published in 2021. While the data reflect the prison population in 2016, this study is still the most recent source for the information used in this study. ↩

-

The data from the Survey of Prison Inmates is not broken down by the state in which individual respondents are incarcerated, but the researchers used the respondent’s state of residence before incarceration as a proxy for state of incarceration. They excluded states from the sample that did not have a known prison minimum wage or copay amount, including Delaware, Maine, Nevada, and Washington. Because three states — California, Virginia, and Illinois — eliminated copays after the 2016 administration of the Survey, they are still included in this sample, although they no longer charge medical copays. ↩

-

For the purposes of calculating an average week’s wage in prison, the authors used our estimate of a 31.75 hour work week (an average workday of 6.35 hours). Not everyone in prison works, but for those that do, incarcerated workers in regular, non-industry prison jobs (i.e., jobs that are directed by the Department of Corrections and support the prison facility) had an average minimum daily wage of 86 cents in our 2017 analysis. Incarcerated people assigned to work for state-owned businesses (i.e., “industry” jobs that produce goods and provide services that are sold to government agencies) earned between 33 cents and $1.41 per hour on average — roughly twice as much as people assigned to regular prison jobs. For state-specific information on prison wages, an explanation of different types of prison work assignments, and more detail on the methodology behind these calculations, see our 2017 publication, How much do incarcerated people earn in each state? ↩

-

This study utilized a definition of chronic conditions that included ever having hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, stroke, asthma, cirrhosis, HIV, or cancer or currently having kidney disease, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or joint disease. The Bureau of Justice Statistics, in their report on health of people in prison based on the 2016 Survey, estimated that 504,000 people in state prisons and 57,700 people in federal prisons currently had at least one chronic physical condition (including cancer, high blood pressure, hypertension, stroke-related problems, diabetes, high blood sugar, heart-related problems, kidney-related problems, arthritis, asthma, or liver cirrhosis). The estimated number of incarcerated people who have ever had a chronic physical condition was upwards of 715,000. ↩

-

The researchers categorized psychotic disorders, bipolar/manic disorders, and personality disorders as “chronic” mental health conditions. ↩

-

Severe psychological distress was calculated using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) that was included in the 2016 Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey. The K6 scale is composed of six survey questions regarding one’s mental state in the past 30 days and a composite score of 13 or higher reflects “severe psychological distress.” ↩

-

Research has found a robust association between psychological distress and mortality, and higher levels of psychological distress are associated with suicide, which continues to be a growing cause of death in prisons and jails. ↩

-

It is widely understood that inconsistent use of prescription medications (often called “medication non-adherence” in medical research) for mental health conditions is associated with poorer outcomes, including diminished treatment efficacy, worsened symptoms, and reduced responsiveness to future treatments. ↩

-

The statistical analysis of the effects of copays on access to pregnancy-related healthcare were not statistically significant, likely due — in part — to a small sample size (only 178 pregnant people were in prisons without co-pays). ↩

-

This quotation is published in the study’s appendix. Dr. Homer Venters previously served as chief medical officer of the New York City jail system and currently serves as a Federal Court Monitor of health services in jail and prison settings. ↩

-

Because of the small sample size, the researchers combined the Survey of Prison Inmates’ non-Hispanic racial categories of American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and “other” race (i.e., a different racial identity that does not fit in the racial categories the Bureau of Justice Statistics uses). ↩

-

This increase is not due to a change in definitions between 2004 and 2016, as the authors used the same list of mental health conditions in the 2004 and 2016 iterations of the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Survey of Prison Inmates: depression, anxiety, psychotic disorders, manic disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and personality disorder. In 2016, the Bureau of Justice Statistics added an additional mental health measure — severe psychological distress — but since this was not used in the 2004 iteration, it is not included in the change in the number of people reporting mental health conditions. ↩