Massachusetts women do not need a new jail

The Mass. Senate is considering building a new women's jail. We offer a number of reasons why this is a bad idea.

by Wendy Sawyer, March 29, 2019

The Massachusetts Senate is once again considering construction of a new jail for women in Middlesex County. But I would caution against any expansion of correctional facilities without first reckoning with the inherent harms of jail incarceration and exploring better alternatives.

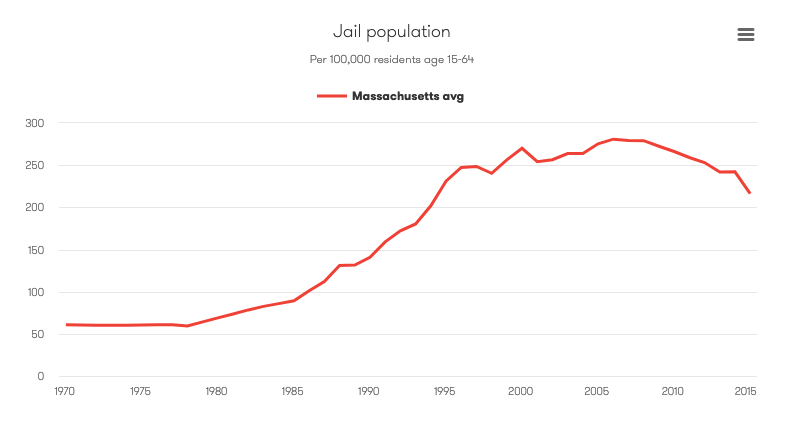

The proposal – Senate 1851 – would “establish a commission to identify a suitable location for a justice complex” in Middlesex County. I find it interesting that the commission is to identify a location, rather than consider whether a jail is needed at all. According to the text of the bill, this proposal is in line with a law passed in 2008 to expand jail capacity. But that law was passed in the wake of the state’s highest-ever rate of jail incarceration; since then, the state’s jail rate has seen a steady decline. This begs the question: why would the state need more capacity, when jail rates are down?

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that jail incarceration rates in Massachusetts have fallen over the past decade.

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that jail incarceration rates in Massachusetts have fallen over the past decade.

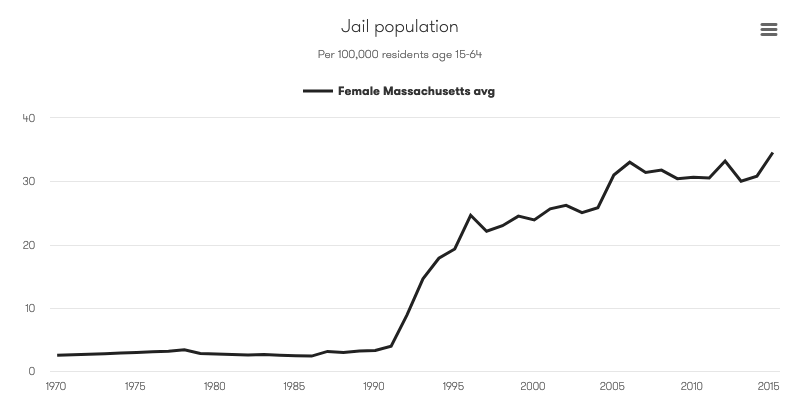

Despite the overall downward trend in the state’s jail rate, two groups have been jailed at steady or increasing rates: women and people being detained pretrial – and these are the two populations being used to justify the “need” for a new jail.

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that the female jail rate in Massachusetts has risen steadily since the early 1990s.

The Vera Institute of Justice’s Incarceration Trends tool shows that the female jail rate in Massachusetts has risen steadily since the early 1990s.

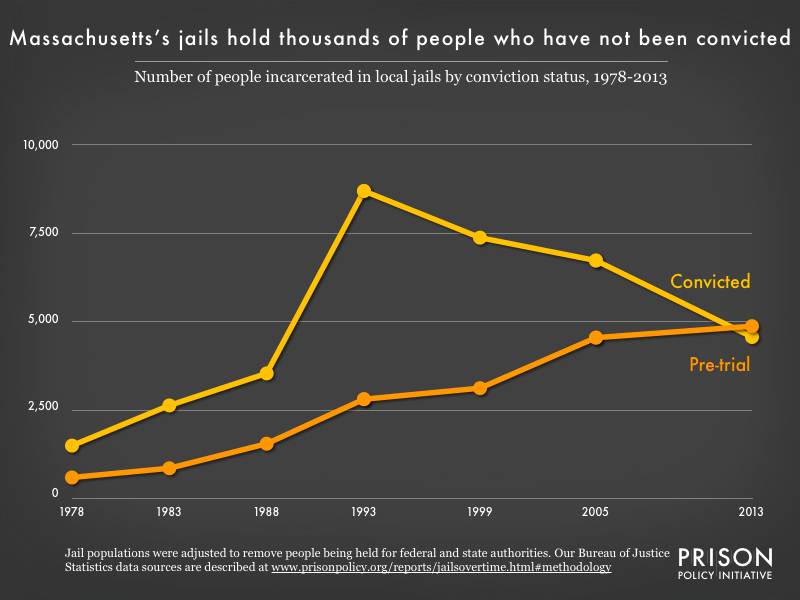

The pretrial population in Massachusetts jails has increased for decades, while the number of people serving sentences there has fallen dramatically since 1993.

The pretrial population in Massachusetts jails has increased for decades, while the number of people serving sentences there has fallen dramatically since 1993.

But despite the growth in the female and pretrial jail populations, there are some important arguments against building a new jail to hold these groups.

First, jails are uniquely harmful to women, and their needs are better met by community-based programs and services. Women in jails have higher rates of mental health and substance use disorders, and often have a history of abuse or other trauma; incarceration more often exacerbates these problems than alleviates them (for more information, see the “Context” sidebar in our 2018 report). As of December 2018, the Massachusetts Department of Corrections (DOC) reported that “74% [of women held by the DOC] were open mental health cases, 15% had a serious mental illness (SMI), and 56% were on psychotropic medication” – all rates roughly double those of the male population. Women in jails (especially women of color) are also poorer, on average, than their male counterparts, and therefore often are detained pretrial because they can’t afford even low bail amounts. Furthermore, separation from children leads many women to accept plea deals just to get out of jail sooner, which in turn leaves them with criminal records that may not reflect actual guilt or innocence.

Second, pretrial detention leads to worse outcomes, from high risk of suicide to increased likelihood of conviction, longer sentences, and reoffending. Yet pretrial detention has driven all of the jail growth in the U.S. over the last 20 years, which means that jails – like the one being proposed – are being built because more people who have not been convicted and are legally presumed innocent are being locked up. This trend reflects an increasing reliance on money bail – essentially, wealth-based release decisions – rather than an increase in “dangerousness” or flight risk. According to DOC data, the female pretrial population held by the DOC has increased 18% since 2010. If Massachusetts wants to relieve jail overcrowding, it should start by minimizing the number of people held pretrial, especially those who are there because they can’t afford bail.

Another problem that should be addressed before expanding jail capacity is the racial disparity evident in the state’s female pretrial population. As of Jan. 1, 2018, nearly a third (32%) of the women held by the DOC (in Framingham) were being detained pretrial. However, this proportion varied by race and ethnicity. 44% of Hispanic women and 35% of Black women held by the DOC, versus 31% of “Other” and 29% of white women, were held pretrial.

The idea to build a new women’s jail is not a new one. For years, a handful of Massachusetts counties have sent women detained pretrial to the women’s prison, MCI-Framingham, because they didn’t have separate jail space for women in the county jails. And for years, MCI-Framingham was overcrowded for precisely that reason. In 2007, the state opened a new jail for women farther west, and sent women from counties without separate women’s facilities that were west of Worcester to the new jail to await trial or serve their sentences. The result? Women jailed there were farther from crucial contacts, including their families and children, and their lawyers – which in turn made it harder to prepare their defense. Now, lawmakers want to build again, this time near the existing Framingham facility in southern Middlesex County.

The legislators behind the new jail project undoubtedly see a new jail as an “upgrade” for the state’s incarcerated women, since it would alleviate crowding and would be more updated housing than the nearly 150-year-old prison. But the real solution for women in jails would be to return to their communities. They would be better served awaiting trial at home, participating in diversion programs, and getting needed treatment and support for underlying problems through community-based programs. If legislators care about improving conditions for justice-involved women, they should focus on investing in community services and alternatives to incarceration that interrupt women’s distinct pathways to prison – not just building them newer, bigger, jails.

What you are failing to take into consideration is that MCI-Framingham is very old and becoming unsafe to house inmates. A new prison would be beneficial for not only the inmates, but also the staff that are working there. Also, new programs are being instituted (Medication Assisted Treatment) and it is very challenging due to a lack of space to safely carry out the program without disruption to the entire facility.

Fair, but we’re not arguing that the old jail is fine – we’re arguing that rather than building a new jail, counties should look for ways to reduce the number of women who go to jail at all. (For instance, through pretrial reform, which would reduce the number of legally innocent women in jail.)