Research roundup: The positive impacts of family contact for incarcerated people and their families

The research is clear: visitation, mail, phone, and other forms of contact between incarcerated people and their families have positive impacts for everyone — including better health, reduced recidivism, and improvement in school. Here’s a roundup of over 50 years of empirical study, and a reminder that prisons and jails often pay little more than lip service to the benefits of family contact.

by Leah Wang, December 21, 2021

To incarcerated people and their families, it’s glaringly obvious that staying in touch by any means necessary — primarily through visits, phone calls, and mail — is tremendously important and beneficial to everyone involved. Yet prisons and jails are notorious for making communication difficult or impossible. People are incarcerated far from home and visitation access is limited, phone calls are expensive and sometimes taken away as punishment, mail is censored and delayed, and video calls and emerging technologies are all too often used as an expensive (and inferior) replacement for in-person visits.

Prison- and jail-imposed barriers to family contact fly in the face of decades of social science research showing associations between family contact and outcomes including in-prison behavior, measures of health, and reconviction after release. Advocates and families fighting for better, easier communication behind bars can turn to this research, which demonstrates that encouraging family contact is not only humane, but contributes to public safety.

In-person visitation is incredibly beneficial, reducing recidivism and improving health and behavior

The positive effects of visitation have been well-known for decades — particularly when it comes to reducing recidivism. A 1972 study on visitation that followed 843 people on parole from California prisons found that those who had no visitors during their incarceration were six times more likely to be reincarcerated than people with three or more visitors. A few years later, researchers found similar results in a study of people paroled from Hawaii State Prison.

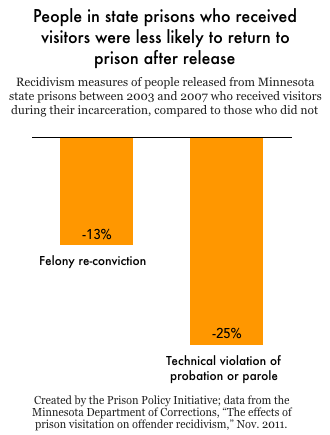

Since the 1970s, the body of evidence in favor of prison visitation has only grown. In 2008, researchers found that among 7,000 people released from state prisons in Florida, each additional visit received during incarceration lowered the odds of two-year recidivism by 3.8 percent (in this study, recidivism was defined as reconviction). Findings out of Minnesota a few years later were similar: Receiving one visit per month was associated with a 0.9 percent decrease in someone’s risk of reincarceration; better yet, each unique visitor to an incarcerated person reduced the risk of re-conviction by a notable 3 percent.1 Among people who received visits during their incarceration, felony re-convictions were 13 percent lower and revocations for technical violations of parole were 25 percent lower compared to people who did not receive visits.

Visitation is also correlated with adherence to prison rules. In 2019, an Iowa researcher found that in-prison misconduct (as measured by official citations) was reduced in people who received visits at Iowa state prisons. Based on these results, one additional visit per month would reduce misconduct by a further 14 percent. “Probably as a direct result of the reduced misconducts,” the study’s author notes, “a similar increase in visitation would also reduce time served by 11 percent.”

These findings add to other recent studies linking visitation and reduced prison misconduct. The timing of visits may matter, as visiting “privileges” can swiftly be taken away as a cruel punishment: According to one study, misconduct tended to decrease in the three weeks before a visit. This may explain why more frequent visits lead to more consistent good behavior, better overall outcomes and post-release success. Families who visit, concluded Holt and Miller in the California study, are a “prime treatment agent” for incarcerated people.2

Research has also found that visitation is linked to better mental health, including reduced depressive symptoms — an important intervention for the isolated, stressful experience of incarceration. Yet even before the pandemic halted visitation, and despite these known benefits, correctional facilities have made visitation hard due to remote locations, harsh policies, and the financial incentives to replace visits with inferior video calls.

Consistent phone calls to family improve relationships

Phone calls tend to be more common than in-person visitation, as they involve fewer logistical barriers. In fact, the key studies we found reveal that 80 percent or more respondents used phone calls to contact family, far more than the number receiving visits, and sometimes more than those using mail to keep in contact.3 As with visitation, family phone calls are shown to reduce the likelihood of recidivism; more consistent and/or frequent phone calls were linked to the lowest odds of returning to prison.

A 2014 study of incarcerated women found that those who had any phone contact with a family member were less likely to be reincarcerated within the five years after their release. In fact, phone contact had a stronger effect on recidivism compared to visitation, which the study also examined.

Of course, reduced recidivism is not the only benefit. A 2020 survey of incarcerated parents showed that parent-child relationships improved when they had frequent (weekly) phone calls.

These positive findings have not gone unnoticed by senior policy makers: “Meaningful communication beyond prison walls helps to promote rehabilitation and reduce recidivism,” explained Mignon Clyburn of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in a 2015 statement on the high cost of phone calls. “In a nation as great as ours, there is no legitimate reason why anyone else should ever again be forced to make these levels of sacrifices, to stay connected.”4

Given the frequency and importance of phone calls from prisons and jails, their prohibitive cost in many jurisdictions and the loss of phone “privileges” as a punishment are both inhumane and counterproductive.

Mail correspondence is a lifeline, and taking it away only hurts families

Mail is widely understood as a major lifeline for incarcerated people, with some literature finding that it’s the most common form of family contact.The fulfilling feeling of receiving personal mail, the ability to write and read (and reread) mail at one’s own pace, and the relatively low cost of a letter mean that it’s a highly practical and cherished mode of communication, universal to people both inside and outside of prison. And while prison mail hasn’t taken center stage in academic literature, some of the studies mentioned earlier did examine mail contact as part of their methods, finding that it contributes to parent-child attachment and relationship quality.

Yet mail is another example of a service whose benefits become obvious once it’s under attack. In 2007, notoriously cruel Maricopa County, Arizona, sheriff Joe Arpaio instituted a postcard-only policy in the county jail, with sheriffs in at least 14 states following suit. These postcard-only policies severely limit parents’ and children’s ability to stay in touch. A study of incarcerated parents in Arizona cited mail as the most common mode of communication with their children, and those who used mail contact reported improved relationships with their children as compared to the year before their incarceration. Postcards also change the economic argument for mail correspondence: With their tiny physical space available for writing, we found that relaying information on a postcard is about 34 times as expensive as in a letter.

In recent years, other correctional systems have embraced another mail-restriction policy that advocates know is harmful: The telecom company Smart Communications has created “MailGuard,” a mail digitization service marketed as a response to (exaggerated) claims of contraband entering prisons through the mail. MailGuard’s scans of letters and photographs tend to be low-quality, and privacy is clearly violated as one’s mail is opened and scanned. We’ve criticized this practice and maintain that mail scanning is a poor substitute for true mail correspondence.5

Video calling and emerging technologies could enhance carceral contact if they weren’t prohibitively expensive

Sometimes billed as “video visitation,” video calling from prisons and jails allows families to connect virtually. Used effectively as a supplement, video calls could help eliminate many of the barriers that in-person visitation presents. However, we’ve argued time and time again that these calls fail to replicate the psychological experience — and therefore benefits — of in-person visitation, and should never be used as a replacement. A 2014 survey found incarcerated people in Washington State were pleased when video calling allowed family to see them, but extremely frustrated by the cost and significant technical challenges of the software. Video calling is a “double-edged sword” providing a mediocre service while lining the pockets of private corporations.

Most advocates and groups (including the American Correctional Association) agree that video calling should only supplement in-person visitation, not replace it entirely. But anecdotally, some corrections officials offer video calling only, and promote it as a safer and more efficient option to visitation. (In terms of safety, the argument that most contraband is introduced into prisons through visitation is a myth we’ve busted.)

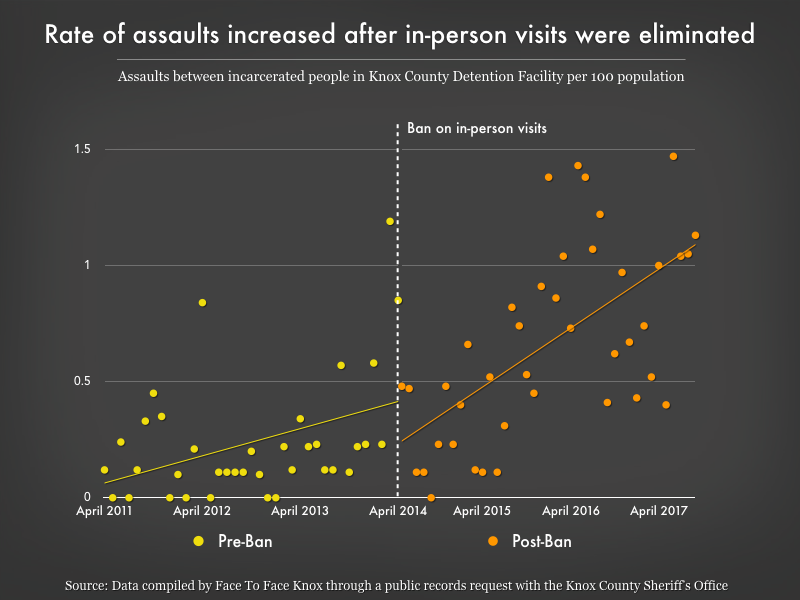

In fact, taking away visitation can make prisons and jails less safe. For example, when in-person visits were banned at the jail in Knox County, Tennessee, in favor of video-only visitation, incarcerated people lost the opportunity to maintain healthy social connections. As a result, assaults between incarcerated people and assaults on staff increased in the months after the ban on visits was implemented. Data also show that, similar to the Iowa study mentioned earlier, disciplinary infractions in the jail increased after the ban.

The Knox County research wasn’t an isolated finding: In Travis County, Texas, there was an escalation of violence and contraband after that jail switched from offering both video calls and visitation for a few years, to banning in-person visitation altogether. The change also reduced overall family contact: The number of video calls dropped dramatically compared to the average number of in-person visits that had happened at the jail before the policy change. As it turns out, the availability of both in-person visitation and video calling actually increased the average number of in-person monthly visits. And unsurprisingly, visitors who were surveyed overwhelmingly preferred in-person visitation to video calling. In 2015, the Travis County Sheriff’s Office reinstated in-person visits.

Technologies like video calling (and electronic messaging) have the potential to improve quality of life for incarcerated people and help correctional administrators run safer and more humane facilities. New research suggests that video calls may even help reduce recidivism (but only when they supplement in-person visits). Sadly, the promise of these new services is often tempered by a relentless focus on turning incarcerated people and their families into revenue streams.

Families endure tremendous hardship due to incarceration, but staying in touch can mitigate negative impacts

Many of the studies discussed here focused on the benefits of family contact for incarcerated people. But what about their families — do they gain from the time spent visiting, writing, or calling? Research says yes, family contact also provides relief to the family of an incarcerated person. This is important, because simply having an incarcerated loved one indicates poorer health and a shorter lifespan. In particular, children — the “hidden victims” of incarceration — are at increased risk for mental health problems and substance use disorders, and face worse intellectual outcomes compared to children without an incarcerated family member. (Youth can themselves be confined in detention facilities, turning parents into visitors; similar to the research explored earlier, visitation of confined youth was remarkably beneficial.6)

Research suggests that families who visited during a loved one’s incarceration show improved mental health measures and have a higher probability of remaining together after release. And a 1977 study, explained in a larger review of family contact research, found that children who had displayed concerning behavior upon their fathers’ incarceration showed improved behavior after visiting with their fathers.

The R Street Institute sums it up nicely: Supportive family relationships can promote psychological and physiological health for incarcerated people and their loved ones, at a time when everyone’s health is otherwise deteriorating. When done well, visitation can ease anxiety in children and mitigate some of the impacts on strained interpersonal relationships. Serving families at this most critical period simply makes communities healthier.

Making family contact readily available should be a no-brainer for prisons and jails

Of course, staying in touch with an incarcerated person is almost never easy. There can be great distress and tension as a family navigates its role, and the inconsistent timing and frequency of contact can be unsettling to someone whose incarceration is overly predictable and tedious, while life outside can be anything but.

Still, academic research is unified in its message that family contact during incarceration provides immense benefits, both during incarceration and the reentry period. Prisons and jails should make all types of family contact safely and equitably available, and end the practice of taking contact away as a punishment for rule violations. And with no certain access to visitation as the pandemic wears on, families and incarcerated people should receive more phone and video time, fewer fees, and better mail options in order to preserve family ties and the critical benefits that result from family contact.

Below, we’ve compiled all of the research discussed and linked above as a bibliography for our readers. And for further reading on the harmful restrictions on communication between incarcerated people and their loved ones, see our resources on visitation and our campaigns fighting for phone, mail, and visitation justice.

Bibliography

Adams, D. & J. Fischer (1976). The effects of prison residents’ community contacts on recidivism rates Paywall :(. Corrective & Social Psychiatry & Journal of Behavior Technology, Methods & Therapy, 22(4): 21-27.

Agudelo, S.V. (2013). The Impact of Family Visitation on Incarcerated

Youth’s Behavior and School Performance: Findings from the Families as Partners Project. Vera Institute of Justice Family Justice Program.

Bales, W. D. & D. P. Mears (2008). Inmate Social Ties and the Transition to Society: Does Visitation Reduce Recidivism? Paywall :( Journal of Research in Crime and Deliquency 45(3): 287-321.

Barrick, K. Lattimore, P. K., & Visher, C. A. (2014). Reentering Women: The Impact of Social Ties on Long-Term Recidivism. The Prison Journal 94(3): 279-304.

Bertram, W. (2021). The Biden Administration must walk back the MailGuard program banning mail from home in federal prisons. Blog post. Prison Policy Initiative.

Cochran, J. C. (2012). The ties that bind or the ties that break: Examining the relationship between visitation and prisoner misconduct Paywall :(. Journal of Criminal Justice 40(5): 433-440.

Clyburn, M. (2013). Statement re: Rates for Interstate Inmate Calling Services, WC Docket 12-375. Federal Communications Commission.

De Claire, K. & L. Dixon (2015). The Effects of Prison Visits From Family Members on Prisoners’ Well-Being, Prison Rule Breaking, and Recidivism: A Review of Research Since 1991. Trauma Violence & Abuse 18(2): 1-15.

Digard, L., J. LaChance, & J. Hill (2017). Closing the Distance: The Impact of Video Visits in Washington State. Vera Institute of Justice.

Duwe, G. & V. Clark (2011). The Effects of Prisoner Visitation on Offender Recidivism. Criminal Justice Policy Review 24(3): 271-296.

Duwe, G. & S. McNeeley (2020). Just as Good as the Real Thing? The Effects of Prison Video Visitation on Recidivism. Crime & Delinquency 67(2): 1-23.

Fulcher, P. A. (2013). The Double-Edged Sword of Prison Video Visitation: Claiming to Keep Families Together While Furthering the Aims of the Prison Industrial Complex. Florida A&M Law Review 9 (1): 83-112.

Hairston, C.F. (1991). Family Ties During Imprisonment: Important to Whom and For What? Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 18(1): 87-104.

Haverkate, D. L. & Wright, K. A. (2020). The differential effects of prison contact on parent-child relationship quality and child behavioral changes. Corrections: Policy, Practice, & Research 5: 222-244.

Holt, N. & D. Miller (1972). Explorations in Inmate-Family Relationships. Sacramento, Calif.: California Department of Corrections Research Division.

Lee, L. M. (2019). Far From Home and All Alone: The Impact of Prison Visitation on Recidivism. American Law and Economics Review 21(2): 431-481.

Mooney, E. & N. Bila (2018). The importance of supporting family connections to ensure successful re-entry. R Street Institute.

Poehlmann, J. (2005). Children’s Family Environments and Intellectual Outcomes During Maternal Incarceration Paywall :(. Journal of Marriage and Family 67(5): 1275-1285.

Renaud, J. (2014). Video Visitation: How private companies push for visits by video and families pay the price. Grassroots Leadership and Texas Criminal Justice Coalition.

Renaud, J. (2018). Who’s really bringing contraband into jails? Our 2018 survey confirms it’s staff, not visitors. Prison Policy Initiative.

Sakala, L. (2013). Return to Sender: Postcard-Only Mail Policies. Prison Policy Initiative.

Siennick, S. E. et al (2012). Here and Gone: Anticipation and Separation Effects of Prison Visits on Inmate Infractions Paywall :(. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 50(3): 417-444.

Tahamont, S. (2011). The Effect of Visitation on Prison Misconduct [poster presentation]. IGERT Program in Politics, Economics and Psychology at University of California, Berkeley.

Wagner, P. & A. Jones (2019). State of Phone Justice. Prison Policy Initiative.

Widra, E. (2016). Travis County, Texas: A Case Study on Video Visitation. Prison Policy Initiative,

Widra, E. (2021). New data: People with incarcerated loved ones have shorter life expectancies and poorer health. Prison Policy Initiative.

Footnotes

-

In this study, both family members and non-family members like mentors and clergy were connected to this reduced risk of recidivism. ↩

-

More importantly, Holt and Miller assert that “correctional systems can no longer afford to incarcerate inmates in areas so remote from their home communities as to make visiting virtually impossible.” Located in inconvenient areas for many, prisons are getting in their own way when it comes to treatment and rehabilitation. ↩

-

For example, in a 2020 study examining contact between children and their incarcerated female parents, researchers found that when children communicated with their parents in prison, 76% of those who used phone contact did so weekly, 45% who used mail did so weekly, and 31% who visited did so weekly. ↩

-

The FCC, which regulates the cost of phone calls in the United States, has made strides in capping prison and jail phone rates and shutting down abusive practices by telecom companies. (We have successfully fought for some of these changes.) ↩

-

While there are still many harmful policies in place, some prisons and jails have backed down when families and the courts call out these attacks on mail, such as in Portland, Oregon, in 2012 and in Santa Clara County, California, in 2015. ↩

-

A study of family visitation frequency in Ohio juvenile facilities found that youth who were visited by family regularly (defined as weekly) had a grade point average that was 2.1 points higher than youth who were infrequently or never visited. Additionally, behavioral incidents decreased as the overall frequency of visitation increased among the families of confined youth. The researchers note that white youth in this study had higher GPAs than nonwhite youth, and that factors beyond their control could be contributing to the calculation of GPAs of youths of different races, so they suggest that the results merit further exploration. Still, frequent family visitation did improve GPAs after controlling for race and other variables. ↩