All profit, no risk: How the bail industry exploits the legal system

By Wendy Sawyer

October 2022

Press release

Reporter guide

- Table of Contents

- Why forfeitures matter

- Millions in unpaid forfeitures

- Strategies to avoid paying

- Lobbying for loopholes

- Complicated process

- Grace periods

- Piggybacking off pretrial services agencies

- Strict deadlines and requirements

- Bond agents can get money back

- Failure to penalize for default

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Appendix tables

The image of the bail bondsman who brings fugitives to justice is a familiar and powerful one; unfortunately, it’s more fiction than fact. In this report, we explain why the central tenet of the industry — that “it provides a public service at no cost to the taxpayer”1 — is a lie that the industry uses to defend its profitable position in the American criminal legal system. In reality, bail bond companies and their deep-pocketed insurance underwriters are almost always able to avoid accountability when they fail to do their one job - to ensure their clients’ appearance in court. The result? They get richer, defendants get poorer, and local law enforcement does their job for them, returning defendants to court on the taxpayer’s dime.

When their clients do not appear in court, bail companies are supposed to fulfill their obligations and pay the “forfeited” bail bonds. But journalists and local government officials around the country have independently discovered that their particular city or county is owed thousands or even millions from bond agents for unpaid bail bonds that have been ordered forfeit. Many of these jurisdictions have yet to put together that this is not simply a local problem, but a systemic problem with commercial money bail — and one that has been intentionally created by the bail industry to protect its profits.

This report brings together evidence from jurisdictions around the country, as well as from previous research, to show that the system is dysfunctional by design, benefitting the commercial bail bond industry far more than its clients or the public. Every bail company’s primary goal is to maximize their own returns, and paying a client’s bond when he or she fails to appear in court runs contrary to that goal. As this report shows, bail companies will not pay forfeitures unless they are forced, and forcing these well-resourced companies to pay what they owe costs counties a great deal of time and money — especially when the bail industry continues to lobby for and defend the legal loopholes that allow them to avoid accountability.

This report presents and explains:

- The six major practical, legal, and procedural loopholes that the industry exploits and works to expand, which keep them from having to pay up when defendants don’t appear in court;

- A compilation of previously isolated examples of investigatory research, news stories, and illuminating statements from government and industry actors, which together show a pattern of problems with commercial bail systems avoiding accountability across at least 28 states; and

- An argument that these problems are likely to exist in every state that allows commercial bail companies to post bonds, and details suggesting where concerned citizens and officials might look for problems in their own jurisdictions.

While this report details the many legal advantages bail companies have secured for themselves, we conclude that “fixing” the system is not a viable option. Rolling back all of the laws the industry has lobbied for would be nearly impossible, especially in the face of its immense political influence. Instead of trying to “fix” a broken money bail system, or continuing to subsidize private bail companies, counties should implement alternatives to money bail that have been shown to work.

By now, it should go without saying that the criticisms of the bail industry are many, and its exploitation of the courts isn’t even the most important one. Exposes of the industry’s abuses and corruption abound, and researchers have shown time and again how the harms of money bail disproportionately impact the poor and communities of color, and that the system undermines justice and public safety. But with this report, we hope to show that the industry’s one major argument in its own defense is, in fact, built on a lie.

Why bail forfeitures matter

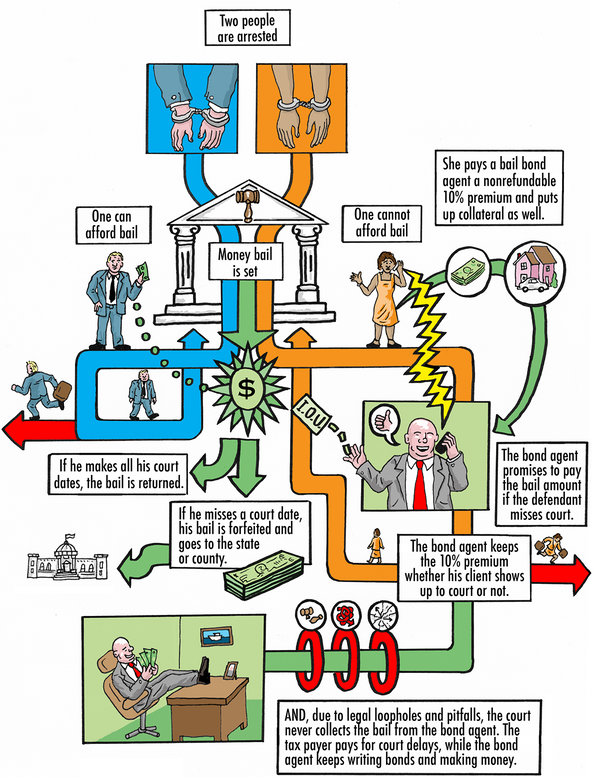

Bail bond companies “bond” out jailed people who cannot afford bail in exchange for a nonrefundable fee, and promise to “forfeit” (pay) the full bail amount to the courts if their client fails to appear in court.

The bail forfeiture process — in which localities collect the money that bail bond companies owe them — is the only part of the process that holds commercial bail bond companies accountable. Yet, throughout the country, courts fail to actually extract this money owed. In a 2015 report, a Utah State Courts committee found:

“At present, the supposedly powerful incentive that commercial bail bonds create to ensure court appearance does not exist. If commercial bail bonds are to have any utility, the forfeiture process must be simplified and improved… Unless and until these steps are taken, these bonds truly are not worth the paper they are written on.”

A defendant’s “failure to appear” initiates a slow, convoluted bail forfeiture process: one with countless loopholes that favor bond companies, and that very rarely actually results in the bond company paying the court.10 A former County Prosecutor in New Jersey suggests “’the public would be appalled’ if it knew how little of the forfeited bail owed was turned over.”

Most of the time, when a defendant misses a court date, he or she will appear on their own shortly after;11 they haven’t “fled” but more often cite forgetfulness or logistical reasons for their absence. Even when they don’t return on their own, local law enforcement picks up the slack, returning more defendants to custody than bond agents do. The law gives bail bond companies a wide grace period in which the defendant tends to return either on their own or after being stopped by law enforcement.

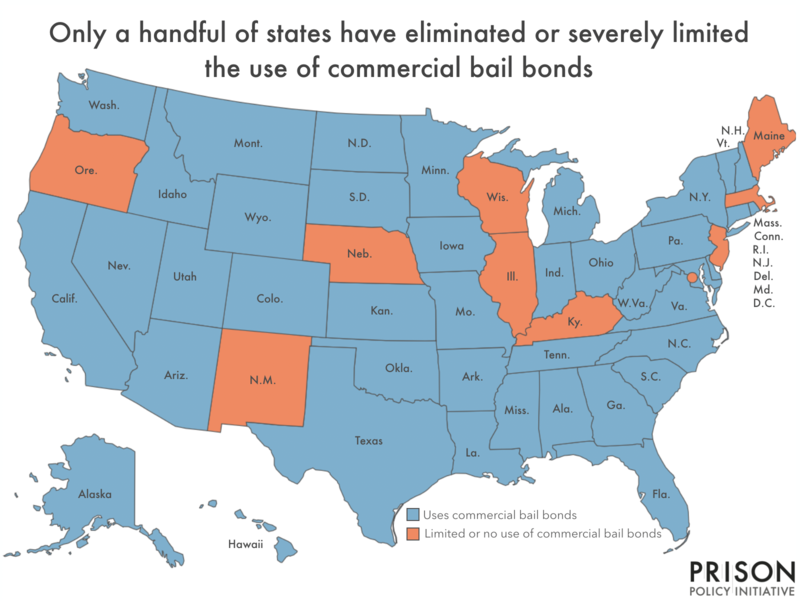

Despite this broken system (in which bail bond companies extract money from defendants and waste court resources without providing meaningful services in exchange), commercial bail bond agents are allowed and regularly operate in over 40 states. The money bail system is changing rapidly, with Illinois becoming the first state to eliminate all forms of money bail in 2021. But the commercial bail industry remains firmly entrenched across most of the U.S., despite the harms it causes.

Bail companies owe counties millions in unpaid forfeitures

Over the past twenty years, journalists and government agencies have discovered that many forfeited bonds in their local jurisdictions go unpaid or otherwise fall through the cracks. Our survey of these reports found that in at least 28 states, jurisdictions have reported serious problems with bond forfeitures, including: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, and West Virginia.12 Some of these states, of course, have since reformed or largely abandoned their money bail systems, but their experiences with the commercial bail industry are nevertheless useful in illuminating this widespread problem.13

The audits and investigative reports we compiled describe loopholes in the bail forfeiture process that bond agents and surety companies exploit to avoid paying huge sums owed to the courts — ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars. For example:

- California: Estimates of the amount bond companies owe the state each year are well into the millions. In Los Angeles County, where over 99% of bonds are surety bonds, $1.1 million in forfeited bonds went unpaid in 2016-17. In San Francisco, too, officials estimate that bond agents successfully avoid paying “millions” of dollars owed to the court each year.14

- Louisiana: One company alone owed Orleans Parish (New Orleans) nearly $1 million; officials in East Baton Rouge reported that bond agents owed them another $1 million.

- Mississippi: As of 2016, private bail agents and companies owed an estimated $1.8 million in unpaid forfeitures. $372,000 was owed to Rankin County alone.

- New York City: In 2011, bond agents and sureties owed over $2 million for 150 cases in which judges ordered bail bonds forfeited.

- Pennsylvania: Northampton and Lehigh counties, both in the Allentown area, found that bail bond agents owed over $1.5 million and $350,000, respectively, in unpaid forfeitures.15

- Texas: Bond agents and sureties in Harris County (Houston) owed an estimated $26 million in unpaid forfeitures, with some cases decades old. Similarly, investigative reporters found agents and sureties owed over $35 million to Dallas County in forfeitures going back decades. And despite an uptick in felony cases, the amount of forfeited bonds collected fell 80% between 2002 and 2011. Finally, agents and sureties in Tarrant County (near Fort Worth) paid less than $1 million of $5 million owed in forfeited bonds between 2009-2012.

- For a list of more examples, see the Appendix table.

To date, almost all of these audits and investigative reports are framed as local scandals with a kind of banal bureaucratic dysfunction at their core; they lay the blame on inept government agencies failing to track, pursue, and collect forfeitures. One of the goals of this report is to demonstrate that these stories are not isolated, but part of a much larger structural problem: the bail industry intentionally and systematically avoids making good on its promises.

These local investigations may have missed the larger, structural pattern that allows the bail industry to consistently avoid financial responsibility, but a few skeptical journalists and advocacy groups have caught on. They observe that the insurance companies that back bail bond companies almost never take losses on bail bonds — unlike similar companies who underwrite surety bonds in other industries. When Mother Jones investigated the financial records of 32 surety companies that underwrite bail bonds, they found that these companies paid less than 1% in bail losses. In comparison, Color of Change and the ACLU report that insurers who underwrite surety bonds for other industries report average losses of about 13%. According to their report, for major bail bond insurer Lexington National, even its negligible reported losses on bail bonds “are mostly a timing issue and are usually recouped.” Another goal of this report, then, is to explain exactly how bail bond companies and their insurers manage to avoid paying any losses with so few regulators and policymakers catching on.

Bail bond companies employ various strategies to avoid paying what they owe

So how, exactly, do bail bond agents and their insurers report losses rounding to zero, when defendants’ “failure to appear” (FTA) rates are typically between 15-30%,16 including about 18% for felony defendants released on surety bail bonds?17 After all, each bonded defendant who misses their court date should, in theory, result in a bond forfeiture.

Our analysis revealed four major strategies bail bond companies routinely employ to avoid forfeitures:

- Bail bond agents consider financial risk, not risk of nonappearance in court, when deciding who to write bonds for. They routinely refuse to write bonds for people they think are too poor to cover any potential losses, no matter how likely a defendant is to appear in court.. Unlike pretrial services agencies, which have to work with all pretrial releasees assigned to them, bail bond companies get to pick and choose their clients. Although the industry likes to present itself as part of the law enforcement sphere, in this way these companies actually act more like lenders than part of the criminal legal system. For example, one New York-based agent profiled by The New Yorker “turn[s] away potential customers if he thinks… the family won’t be able to cover his costs if the defendant disappears.” He reported only one default in two years.

- Bail bond companies pass the risk along to defendants and their loved ones by collecting collateral. Even in the rare cases when bail bond companies actually pay forfeitures, the costs and risk are passed on to the defendants and their co-signers on the bond (typically family). Bond agents generally require collateral in addition to the typical 10% nonrefundable fee — meaning that families are at risk of losing their homes and property to repay the bond company.18

- Bail companies aggressively fight forfeitures in court. Despite the bail industry’s stated purpose to assume responsibility for their clients’ appearance in court,19 the industry quite openly avoids accountability when bonded defendants miss their court dates. Agents, backed by surety companies with deep pockets, fight forfeitures in court and are usually successful. In San Francisco, for example, “bail bond agencies challenge approximately five forfeitures per month. An estimated 75% of these challenges are granted without contest….” A surety company agent in Oklahoma explained why his company paid so little in forfeitures: “We’re more aggressive with our attorneys.”

- And most importantly, the bail industry lobbies for legislation that makes it easier to avoid paying forfeitures. This fourth strategy is the most powerful. The industry has directed its vast resources — $2 billion per year in premiums from defendants and families — to influence policies that shield themselves from risk and protect their profits. A 2016 report by Color of Change and the ACLU Campaign for Smart Justice details many of the industry’s lobbying efforts over the years.20 The next section of this report outlines many of the specific policies the bail industry has passed through its extensive lobbying efforts.

Bond agents have successfully lobbied for policy “loopholes” and “cracks” in the system that allow them to avoid accountability

Bail industry lobbying is at the root of the dysfunctional money bail system. The bail bond lobbying industry is organized, powerful, rich, and has a track record of killing bail reform.21

The industry has worked hand-in-hand with ALEC, the pro-privatization lobby, for decades to block reforms that would hurt their bottom line, and to write and pass laws in their favor throughout the country.22 It has created an array of policies and bureaucratic processes that appear designed to provide bail bond companies every opportunity to avoid paying when their clients miss court dates. Bail companies rely on these procedural loopholes — as well as the tendency of county officials to let forfeitures fall through the cracks — to reap profits while taking on little risk and providing little service to the public.

In the following section, we outline six of these key loopholes, which occur chronologically at each step of the bail forfeiture process. Each of the six help bond companies avoid forfeiting the money they owe. “Fixing” the system — so that courts can collect a large enough share of forfeitures to motivate bond agents to personally ensure court appearance — would require closing these many loopholes. Counties and states undertaking such an effort should anticipate fierce opposition from the well-resourced and litigious bail industry, and should consider whether abandoning commercial bail bonds entirely would be more effective for the court and the taxpayer.23

1. The overly-complicated process means local officials often fail to pursue forfeitures

The failure of local officials to pursue bail forfeitures is a common theme in the audits and reports we reviewed from around the country. Because so many government actors are involved in bond forfeiture cases, the actions — or inaction — of any one official can lead to lost forfeitures. Typically, it’s up to judges to initiate forfeiture proceedings; up to court clerks to notify bond agents and surety companies; up to district attorneys to prosecute agents and companies who default on forfeiture judgments; up to state insurance regulators to suspend or revoke their authority for nonpayment; and up to sheriffs or others who accept bonds to refuse further bonds from those companies. Each of these officials must balance their role in the bail forfeiture process with their other time-sensitive, resource-intensive duties — many of which have higher immediate stakes. Enforcing bail forfeitures often takes a backseat to more urgent court matters.

The process of prosecuting forfeitures is not only competing with more urgent court matters, it is also costly. According to a 2017 report by the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Bail Reform in California, “Courts do not have the infrastructure to follow-up and file lawsuits, and because the bail industry is a for-profit industry, they do not pay expenditures they are not forced to pay. Counties are required to essentially sue the bail companies to receive forfeitures; this court process is lengthy and costly to taxpayers.”

The ultimate result of this division of labor (and financial cost) is that courts often let bail bond agents and sureties fall through the cracks when they fail to produce clients for scheduled appearances. And bond agents rely on this fact: In Pennington County, S.D., “Bail bondsmen… operate virtually risk free under a more than 30-year-old understanding that the courts will not demand payment of a bond when a defendant skips town.” Journalists in that county found 104 cases from 2016 to 2018 in which bond was revoked for failure to appear, yet the court didn’t initiate forfeiture proceedings for a single one.24

Pennington County is not alone: reports we reviewed blamed unpaid forfeitures on the failures of judges, prosecutors, clerks, and other officials in Dallas County, Ala.; Pinellas County, Fla.; Orleans Parish, La.; Albuquerque, N.M.; Oklahoma County, Okla.; Lehigh County, Pa.; Spartanburg County, S.C.; Tarrant, Dallas, and Harris counties in Texas; and the states of Maryland, New Jersey, and Utah.

Instead of individual jurisdictions pointing fingers at the weak links in their own bureaucratic forfeiture process, policymakers should understand that, broadly, the process, and the law itself, is designed to favor bond agents and surety companies.

2. Even when localities pursue forfeitures, bond agents and insurers enjoy long “grace periods” before forfeitures are final

Laws in 38 states grant bond agents a window of time after the missed court date. If the client returns to court in that window, the agent does not need to pay the forfeited bail. These “grace periods” are often quite long — in 10 states, they have at least 6 months25 — and courts often grant extensions. During the grace period, the defendant is often returned to court not by the bond agent, but rather returns voluntarily. People usually do not miss court dates intentionally: A 2019 article in The Appeal points out that failure-to-appear rates in criminal court are similar to no-show rates for medical appointments, which range from 15 to 30%.

Even when defendants don’t return on their own, local law enforcement returns more defendants to custody than bond agents do. For example, in Jefferson County, Colo., commercial bond agents notified law enforcement of defendants’ locations in less than 1% of adult arrests, and brought them to the jail for booking in less than 0.5% of all bookings. “Thus,” according to the county’s Criminal Justice Planning Unit, “almost all defendants with warrants for failure to appear are located, arrested, and booked” by publicly funded law enforcement, not bail agents.26

Similarly, in Salt Lake County, Utah, commercial bond agents in 2015 returned only 13% of the 928 defendants who were released on surety bonds and then missed their court dates. Law enforcement agencies returned the other 87% to court.27 And a recent Michigan report found that “failure to appear” was the most common reason for arrest by police. Since courts typically issue warrants when defendants miss their court date, something as simple as a traffic stop can lead the police to bring a defendant back into custody. And the longer the grace period, the more likely it is that the bond agent can avoid paying the forfeiture with no extra effort on their part. As an assistant District Attorney (“DA”) in North Carolina put it, “If you don’t show up for court, the bondsman sits back and waits because they know the sheriff is going to bring them back.”

3. Bail bond agents can piggyback off of public pretrial services agencies

An even more egregious example of the local legal system subsidizing the bail industry is a practice sometimes called “double-supervising” or “doubling-up,” in which defendants are released by the court under both the surety bond and pretrial services supervision. A Colorado study found that in 8 out of 10 large counties that have professional pretrial services agencies, courts regularly require both financial conditions (usually a commercial bail bond) and supervision by a publicly-funded pretrial service agency. According to the National Association of Pretrial Services Agencies (NAPSA):

“The effect is to make the pretrial services agency a kind of guarantor for the bail bondsman, in effect subsidizing the commercial bail industry by helping to reduce the risk that a defendant released on money bail will not return for scheduled court appearances.”28

Not only does “doubling-up” relieve bond agents from having to monitor their clients, it also burdens pretrial services agencies’ resources, which should be reserved for defendants for whom they have sole responsibility.

4. Courts have to adhere to strict requirements and deadlines to pursue forfeitures

While state laws and judicial discretion allow bond agents months of extra “grace period” time to avoid forfeiture, the court itself must adhere to strict deadlines in the bureaucratic forfeiture processes, or the bond agent and their insurer can have the forfeiture “set aside” (forgiven).29 In Utah, for example, the clerk is required, within 30 days of the missed court date, to: mail notice of the defendant’s nonappearance via certified mail with return receipt requested; notify the surety of the name, address, and phone number of the prosecutor; deliver a copy of the notice to the prosecutor at the same time notice is sent to the surety; and ensure that the name, address, email address, and phone number of the surety or agent listed on the bond is stated on the bench warrant. And they must do all of this for both the agent and the surety insurance company. Failure to meet any statutory requirement relieves the bail bond agent and insurer of their financial obligation to pay the forfeiture.

State laws often favor “setting aside” forfeitures unless the judge or prosecutor actively pursues judgment. In North Carolina, for example, the bond agent whose client fails to appear can file a motion to set the forfeiture aside during the grace period. They are supposed to attach the reason and evidence for the for motion, but unless the district attorney or other stakeholder objects to the motion within 20 days, the forfeiture is set aside regardless of the reason, evidence, or the absence of either one. In other words, if the DA doesn’t act fast, the bond agent can have a forfeiture set aside just by filing a motion, even if they have no excuse for their client’s failure to appear in court.

In some states, there is also a statute of limitations that dictates how much time the court has to initiate or finalize the forfeiture process after the missed court date. In Kansas, for example, the court must enter judgment within two years of the missed court date; in Texas, it’s four years.

5. Bond agents can get forfeited money back even after they’ve paid it

Even when a county manages to collect the value of a forfeited bail bond from the agent or insurer, many states allow agents and surety companies to seek “remission” (return) of some or all of the money. Typically — at least on paper — only agents who have paid the forfeited amount on time (that is, by the end of the grace period or upon final judgment) are eligible for remission. And generally, the forfeited money is only remitted when the agent either returns the defendant to court or can prove that they had a reason for not producing their client, such as incarceration in another state.30 However, forfeited funds are often returned to bond agents and insurers even when they don’t follow the law. A Florida audit of five counties found that in 23 out of 25 sampled cases where the bond agent failed to pay the bail forfeiture within the grace period, they were granted remission anyway.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), at least 16 states have statutes limiting the period in which agents can ask the court for remission, but these timeframes are generally long, ranging from 6 months in Alabama to 10 years in Maryland. Many other states don’t set any time limits on remission, and leave it to the court to decide. This wide window of opportunity to recoup paid forfeitures is a generous gift to bail bond agents and surety companies at the expense of the counties. When a county spends its scarce resources to pursue a bail forfeiture and is successful, that victory is all too often temporary, as the bond agents can and do ask for their funds back. This practice is among the many reasons why courts often do not even attempt to seek a bail forfeiture.

6. Counties and states fail to penalize bond agents and insurers when they default

Whether intentionally or not, counties and states have been complicit in allowing this industry to operate with little oversight or accountability. In many states with money bail, the only way to enforce bail forfeiture payment is for the government to suspend bail agents’ and surety companies’ authority to write more bail bonds — essentially, to cut off their revenue stream until they pay what they owe. According to the NCSL, at least 23 states have laws allowing officials to take such action. Often, a state’s Insurance Department oversees this aspect of the bail bond industry,31 and it is up to local judges, court clerks, and/or sheriffs to enforce these restrictions (that is, to reject any further bail bonds from the agents or companies in default).32

Several audits and reports we reviewed, however, found that agents and surety companies were able to continue business as usual even when they owed vast sums in forfeited bail. In Dallas County, Texas, journalists found that bail bond agents owed at least $35 million in unpaid forfeitures, yet the county Bail Bond Board “[had] not revoked any bail bondsman’s license for nonpayment in recent years.” In Pinellas County, Fla., auditors found that three surety companies were able to execute over 7,000 new bonds, worth $24 million, when they had outstanding forfeiture judgments and, according to state law, should not have been able to write any. While the regulatory agency responsible for suspending bail bonding activities varies from place to place, it seems that many are unable to track bond forfeitures or follow through with statutory penalties. “Part of the problem,” regulatory agencies explained to The New York Times, “is that they are outmatched and do not have the resources to investigate abuses.”

Even when a bail bond company or agent is cut off from writing further bonds, they often get around the blacklist by simply changing their trade name. Even the Mississippi Bail Agents Association acknowledges that “An old trick in the bonding business when an agent gets cut off or is about to be cut off because of forfeitures is to change agency names.” A 2017 report confirms this practice; an investigation in New York City identified six bail bond companies using fake trade names or aliases that appeared to be unlicensed.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The bail forfeiture process is clearly designed to favor bail bond companies, as evidenced by policies that guarantee:

- The forfeiture process only works if every actor performs perfectly;

- Any procedural error absolves bond companies and insurers of responsibility; and

- Bond agents are credited with the return of the client to court — even years later and regardless of whether they had anything to do with it.

Critically, the policies and practices that allow bail bond agents to escape accountability are typically not available to individuals who are able to pay their own bail. Together, these loopholes amount to a structural bias in favor of commercial bail bond agents that give them more powers and protections, and subject them to fewer penalties, than ordinary people who pay their bail directly instead of paying a fee to a bail company to secure their freedom. These differences affect each stage of the bail process, from access to bond money to the ability to dispute and recoup bail forfeitures.

It’s possible that policymakers conceded to these various procedural and legal loopholes because of the presumed value of surety bonds to the criminal legal system. But the loopholes have chipped away at the forfeiture system so completely that it is now obvious that surety bonds benefit the bail bond industry far more than the legal system or the public.34

So, what can be done to bring more reason and justice to the bail system? Readers might be wondering whether the forfeiture system can be repaired, but we conclude that it would be impossible at this point for localities to go up against the powerful lobbying of the industry and carefully unwind each of the unfair legal advantages it has won for itself. Some scholars and advocates have suggested a strategy of targeting the role of insurance companies that back bail bond companies. Others, including the American Bar Association, have suggested abolishing the use of commercial bail bonds in pretrial release systems, as a handful of states have already done. Finally, many jurisdictions have attempted to reduce the use of money bail by implementing a system that relies on supposedly-objective “risk assessments” to inform pretrial decisions, but experts on these tools cite “grave concerns” about their reliability and neutrality, particularly when it comes to race and ethnicity, and recommend against such reforms. As we have discussed, all bail reform efforts face enormous resistance from the bail industry, which has successfully blocked popular and practical bail reform efforts across the country. As we have discussed, all reform efforts to reduce the use of money bail face enormous resistance from the bail industry, which has successfully blocked popular bail reform efforts across the country.

Instead, it makes more sense for states and localities to end the use of money bail entirely. This, too, would face fierce opposition from the industry,35 but a major fight to end cash bail is more feasible than rolling back dozens of separate procedural advantages across 41 states and thousands of counties. And given the many other, even more harmful problems caused by money bail than the industry’s financial exploitation (as evidenced by previous research), this broader solution would be far more impactful than focusing on commercial bail alone. Illinois has proven that ending money bail at the state level is politically and practically feasible, laying the groundwork for other states to make this major change to their bail systems.

In the interim, until money bail is eliminated, states and local governments should:

- Release most defendants pretrial without monetary conditions36 and without any restrictive conditions, such as by expanding the use of release on personal recognizance, providing all released individuals with voluntary pretrial supports that will facilitate attendance in court (such as court date notification systems), and requiring that judges explicitly assess whether release with voluntary supports would be sufficient to assure court attendance.

- When the court chooses to use monetary conditions to ensure appearance in court, require a determination of the defendant’s ability to pay before setting a bail amount, and rely on other forms of money bail that don’t involve profit motives, such as unsecured bonds or partially-secured bonds (e.g., “percentage” or “deposit” bonds paid directly to the court).37

- To prevent commercial bail companies from profiting from publicly-funded pretrial services through “doubling up,” pretrial services agencies should decline to provide supervision (but not voluntary supports) in cases where money bail is also posted, unless addition of pretrial supervision will clear the defendant’s obligations on the bail bond.38

- As long as commercial bonds are accepted by courts, ensure that all agents, companies, and insurers operate in compliance with consumer protection laws, at a minimum. In addition, consider requiring bond companies to operate in cash, as defendants must, instead of relying on the surety insurance system.

Footnotes

For example, Jeff Kirkpatrick, a Michigan bail bondsman and executive vice president of the Professional Bail Agents of the United States (PBUS) trade association, told The Baltimore Sun, “The bail agents do all the work they do at no cost to the taxpayer. It’s one of those public-private partnerships that work really well.” In another example Dennis Bartlett, Executive Director of the American Bail Coalition repeatedly emphasizes that the industry offers its services “at no cost to taxpayers,” “costs taxpayers $0,” and “the cost of this service is borne solely by the commercial bail industry,” etc., in his paper The War on Public Safety: A Critical Analysis of The Justice Policy Institute’s Proposals for Bail Reform. ↩

While courts in some other countries can impose financial conditions, such as a deposit, for pretrial release from custody, only in the U.S. and the Philippines is “money bail” dominated by for-profit bail bond companies. According to The New York Times (“Illegal Globally, Bail for Profit Remains in U.S.”), “In England, Canada and other countries, agreeing to pay a defendant’s bond in exchange for money is a crime akin to witness tampering or bribing a juror a form of obstruction of justice.” ↩

In a 2016 opinion in a case about the use of phone calls in pretrial processes, Judge Jenny Rivera acknowledged the difficulty of preparing a defense while detained, writing: “Pretrial detention hampers a defendant’s preparation of his defense by limiting ‘his ability to gather evidence [and] contact witnesses’ during the most critical period of the proceedings…. The detained suspect… lacks a similar ability [to a defendant free on bail or their own recognizance] to contact witnesses and gather evidence.” The barriers presented by pretrial detention also makes it harder for defense attorneys to coordinate with the defendant and their family to build mitigation cases or track down witnesses. As a result, people detained pretrial often present a weaker defense than they would have if they had been able to coordinate their defense freely. Indeed, people detained pretrial are more likely to plead guilty just to get out of jail, more likely to be convicted, and more likely to get longer sentences than those released pretrial. ↩

Two reports from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reveal that the percentage of felony defendants in large urban counties who were released pretrial on financial conditions (i.e., money bond) by state courts has grown dramatically since the early 1990s. In the 2007 report, BJS authors write “From 1990 to 1998, the percentage of released defendants under financial conditions rose from 24% to 36%, while non-financial releases dropped from 40% to 28%.” According to the 2013 report, by 2009, 61% of pretrial releases involved financial conditions, and “Nearly all of this increase was due to a rise in the use of surety bonds, which accounted for nearly twice the percentage of releases in 2009 (49%) as in 1990 (24%).” ↩

According to bail expert Timothy R. Schnacke, who authored Fundamentals of Bail: A Resource Guide for Pretrial Practitioners and a Framework for American Pretrial Reform, published by the National Institute of Corrections in 2014, “[E]ver since 1968, when the American Bar Association openly questioned the basic premise that money serves as a motivator for court appearance, no valid study has been conducted to refute that uncertainty. Instead, the best research to date suggests … secured money does not matter when it comes to either public safety or court appearance, but it is directly related to pretrial detention.” ↩

Because of these premiums, the use of commercial bonds — often the only option for people with fewer financial resources — is more expensive in the long run than paying the court directly. A defendant who pays the court out-of-pocket is later refunded the bond amount if they make all required court appearances. But a defendant that uses a commercial bond agent will not be refunded the premium, regardless of court appearance, and will owe the full bond amount (not just the remaining 90%) to the bond agent if the bond is forfeited. ↩

The insurance companies make clear in their contracts that they are only liable for forfeited bonds as a last resort. Contractually, the agent is liable for the bond, but the surety company also builds in an additional layer of protection, just in case the agent is unable to pay and the court attempts to collect forfeited bail from the surety. Bond surety companies require bond agents to pay a portion of each bond premium (typically 10%) to a “Build-Up Fund,” which is essentially an escrow account held by the surety company. The company can then use the money in the agent’s “Build-Up Fund” first, rather than paying forfeited bail with its own funds. See the Color of Change and ACLU report Selling off Our Freedom: How insurance corporations have taken over our bail system. ↩

This explanation simplifies the conditions under which bail bond companies are allowed to post bonds instead of cash or property. The court trusts that the bond agent is good for the full bond amount because they must be licensed and the companies they work for must register with the state’s Department of Insurance (or similar agency), including by depositing a certain amount of cash that varies by state. (To get an idea of how much these requirements vary, see the section “How many bonds can a personal surety agency write, backed by the minimum deposit?” in The Marshall Project’s Petty Charges, Princely Profits.) This deposit acts as a reserve in case the surety company fails to pay a forfeiture. Localities may also have rules that bond companies must abide by if they want to do business with their courts: In 2014, the Lehigh County (Penn.) Court created rules requiring bond agents to deposit one dollar for every six dollars of bail bonds they post in an escrow account, among other requirements. Predictably, local bond agents sued to stop these rules from going into effect. ↩

Doyle, Bains, and Hopkins (2019) explain that “American taxpayers spend approximately $38 million a day — or $14 billion a year — on pretrial detention. … Los Angeles County has determined that pretrial detention costs the county $177 per day per person, but release and conditional release cost the county between $0 and $26 dollars per day per person.” As for costs of missed court dates, Clipper, Morris, and Russell-Kaplan (2017) cite an estimated cost of a single “failure to appear” of $1,700 (in 2013 dollars). ↩

Some of courts’ unwillingness to separate bail bond companies from their money stems from a basic legal maxim: “equity abhors a forfeiture.” As a principle, the courts do not want to force a person or entity to take a total loss because they failed to do something; for example, some courts require creditors to complete extra procedural steps before making a co-signer actually pay the full amount of a loan. Against this backdrop, it is not entirely surprising that bond companies benefit from so many built-in legal protections that keep them from losing money. For example, in cases related to bail forfeiture in California, courts have for decades asserted that the relevant Penal Code sections (1305 and 1306) “must be strictly construed in favor of the surety to avoid the harsh results of a forfeiture” (People v. Wilshire Insurance Co. (1975)).

However, it is clear that the bail bond industry has secured protections and advantages for itself beyond what is typical in the surety bond industry, which can be seen by the practically zero losses sustained by the insurance companies backing bail bond companies. As the ACLU found, backers of surety bonds in other industries have losses averaging a much higher rate of about 13%.

Not only is there a double standard between bail bond companies and other sureties, but there is also a double standard between bail bond companies and individual defendants who post their own bail. A person who bails a loved one out of jail directly is much more likely than a bail bond company to pay the full amount if the defendant fails to appear. Interestingly, one California court seemed to suggest that its reluctance to extract owed forfeitures from corporate bail bond companies stems from a desire to protect the individual co-signers who paid collateral with the bond agents: That court noted that “The standard of review… compels us to protect the surety, and more importantly the individual citizens who pledge to the surety their property on behalf of persons seeking release from custody, in order to obtain the corporate bond.” (County of Los Angeles v. Surety Insurance Co. (1984), emphasis added.) Bond companies and their insurers, however, are the clear winners when the law “disfavors” forfeitures.

Looking at the criminal legal system more broadly, civil asset forfeiture is another practice where individuals’ property is regularly seized by law enforcement and forfeited by the government. Police have wide discretion to seize cash and other assets from people, based on suspicions that the property was connected to criminal activity, often even if no charges are filed. The courts then decide whether the government can keep the property. ↩According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics report “Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2009,” 83% of released felony defendants made all court appearances in 2009 (see Table 18). Of the 17% who missed a scheduled appearance, 13% returned within the year, and just 3% had still not returned to court after one year. The BJS analysis does not include whether or not defendants returned voluntarily. ↩

It is entirely likely that similar problems exist, but have not yet been investigated, in other states that use commercial bail bond agents. For example, although we found no reports specifically about unpaid bond forfeitures in Nevada, we found that the state has documented many related problems with its commercial bail system. ↩

Problems with bail forfeitures date back much further, of course. A 1967 Research Bulletin by the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau on Pretrial Release Practices offers a number of historical examples of forfeited but uncollected bail bonds, both personal and commercial: “Courts have often been found quite lax in requiring the bondsmen to pay the forfeited bonds. In the 3-year period from 1956-59, the Municipal Court of Chicago recorded only one forfeited payment of $5,955. A 1960 investigation disclosed that $300,000 in forfeitures had been set aside by one judge. Their reinstatement caused 5 bonding companies to go out of business. A 1962 investigation in Cleveland disclosed an estimated loss to the city of $25,000 from failure to collect personal bonds. Milwaukee discovered an $18,000 loss. Bond collection may also be thwarted by companies inadequately financed to pay when the time comes. North Carolina has lost an estimated $10,000,000 in uncollected forfeitures over the last 10 years from small surety companies that have gone bankrupt. Philadelphia’s collection rate in 1950 was only 20 per cent on forfeited and unremitted bonds. A recent crackdown in Houston produced $70,000 on “bad bonds” in less than one year.” ↩

For more details and other examples from California, see the state’s Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup’s 2017 report, Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice. ↩

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported in 2009 that Philadelphia was owed over $1 billion in forfeited bail from the city’s public - not commercial/private — bail system, from cases dating back as far as the 1970s. The clerk of quarter sessions’ office was blamed, having failed to collect 90 percent of the bail judges had ordered forfeited, and then it was abolished, with judges taking over the bail system. The other Pennsylvania examples cited above involve commercial bail bonds. ↩

According to Bornstein, et al. in “Reducing Courts’ Failure-to-Appear Rate by Written Reminders” (2013), “FTA rates vary depending on jurisdiction and offense type, ranging from less than 10%… to as high as 25-30%….” The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reports an average FTA rate of 17% in its most recent analysis of Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, which uses State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS) data from 2009 (see Table 31). While that BJS report does not list the FTA rates for each county included in the analysis, the previous report in the series does: In 2006, FTA rates among felony defendants in a sample of 39 of the 75 most populous counties in the U.S. ranged as high as 39% in Orange County, Calif., with a median FTA rate of 19% (see Appendix Table 20). ↩

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), in the most recent analysis of its kind, reports that in 2004, felony defendants in large urban counties who were released on commercial bail bonds had an 18% FTA rate, with 3% failing to return to court within a 1-year study period (see page 6 of “Pretrial Release of Felony Defendants in State Courts” (2007)). ↩

As Clipper et. al explain in “The link between bond forfeiture and pretrial release mechanism: The case of Dallas County, Texas” (2017), “the co-signer(s) would be liable to the bond company for the remainder of the bail amount if the defendant remains unavailable. Interestingly, co-signers may have also had liens put in place on their property in order to obtain the bail bond… (e.g., real estate, an auto title, etc.). … At [the time of the final forfeiture hearing], the cosigner(s) becomes civilly liable for the forfeited bond, court costs, and interest.” In an article for AboutBail.com’s CollateralMagazine (an “industry magazine written specifically for bail agents”), Jason Pollack, the “former owner of a bail bond company that never paid a single summary judgment to any court,” explains the purpose of collateral from the bail company’s perspective: “Securing collateral is a protective measure specifically geared towards preventing bail bond companies from suffering financial losses… from forfeitures and summary judgments.” ↩

The American Bail Coalition, which describes itself as “a trade association made up of national bail insurance companies… [that] also includes affiliate bail agent members” explains on its website, “The bail agent… plays an essential role to both the defendant and court by guaranteeing that the defendant shows up for court. If the defendant fails to appear, the bail agent is responsible for either retrieving the defendant and bringing them back to court or paying the full amount of the bond to the court.” (Accessed January 7, 2020.) ↩

The American Friends Service Committee’s Investigate project offers a concise summary of the bail industry’s relationship with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which the American Bail Coalition has called its “life preserver.” In addition to this and the Color of Change/ACLU report, many state and local officials and journalists point to the influence of the bail industry lobby in thwarting reforms and regulations. North Carolina Policy Watch, for example, reported that “[t]he bail industry made more than $300,000 in political contributions to state lawmakers between 2002 and 2016. During that period, the North Carolina Bail Agents Association took credit for helping to pass 60 laws ‘helping N.C. bondsmen make and save more money and protect their livelihood.’” In 2010, the American Surety Company reported that the Indiana Surety Bail Agents Association (ISBAA) and its lobbyists were able to get a bill passed that made it harder for courts to forfeit bonds, the Georgia Association of Professional Bondsmen had passed a bill requiring bail bonds for certain offenses, and Americans for the Preservation of Bail had managed to reduce the amount of money budgeted to Pretrial Services of Virginia, “which will severely diminish their ability to continue operating.” More recently, the New York Times reported, “The California insurance commissioner, Dave Jones, said he had twice tried to get a law passed to pay for bail investigations, but both times it was defeated after lobbying by the bond industry.” And in another example, Porter, Indiana Superior Court Judge David Chidester described the surety bail bond system as “a ruse obtained by bail agents through a strong and influential lobby who cozy up to legislators.” ↩

A Governing.com article, “States Struggle to Regulate the Bond Industry,” describes how states have been outmatched by the bail industry’s resources. In Connecticut, writer Russell Nichols explains, former state Rep. Michael Lawlor “pushed numerous bills to regulate the bail bond business. But, he says, his efforts were no match for the bail industry lobbyists. ‘These bills dealt with setting up a system for overseeing the industry, getting them to play by the rules they were supposed to play by,’ he says. ‘They got derailed each and every year.’” The same article describes how bail bond agents in Broward County (Fort Lauderdale), Florida, successfully lobbied the county commissioners to gut the sheriff’s successful pretrial services program and strictly limit pretrial releases — even after the program had reduced pretrial detention enough to close a wing of the county jail, saving taxpayers $20 million and allowing the county to avoid building a planned $70 million detention center. Another Governing article, “The Fight to Fix America’s Broken Bail System” outlines how the industry killed bipartisan bail reform in Texas that would have caused a hit to industry profits. ↩

To be clear, the bail industry’s lobbying efforts are not limited to the past, nor to its work with ALEC. For a recent example that shows exactly how detailed the industry’s input is when it comes to proposed changes to bail laws, and how much of its input is accepted into legislative language, see “Industry Comments to S.B. 18” (starting on page 19 of the PDF) of this “exhibit document” produced for the Nevada Legislature. And as an indication of how much money the industry pours into anti-reform lobbying, data published by the California Secretary of State shows that two ballot measure committees formed to fight Prop 25 (one sponsored by the American Bail Association and one sponsored by two industry-affiliated companies) spent over $10 million fighting the ballot measure which would have ended money bail in the state. (A breakdown of their expenditures is also available.) ↩

The American Bar Association, in its 2007 ABA Standards for Criminal Justice: Pretrial Release, recommended the “abolition of compensated sureties” (eliminating commercial bail bonds), citing “at least four strong reasons”: (1) The defendant’s ability to post bail through a bail bond agent is unrelated to any potential public safety risk; (2) bond agents are not obligated to prevent criminal behavior by their clients; (3) bond agents’ decisions about what conditions to set for each client are not transparent; and (4) the commercial bail system “discriminates against poor- and middle-class defendants” who can’t afford their premiums or don’t have collateral to put up, so they are stuck in jail even if they post no risk. ↩

The article explains that in Pennington County, this unofficial policy of not pursuing forfeitures is a relic of the 1980s, when the county jail was overcrowded and the county relied on bail bond companies to help decrease its population. ↩

In California, Connecticut, Idaho, Louisiana, Missouri, Nevada, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Utah, the grace period is 180 days or 6 months. In Indiana, there is no “late surrender fee” (portion of the forfeited bond paid to the court) for the first 120 days; it then increases over time, until, after 366 days, 100% of the bond is finally forfeited. See the National Conference of State Legislatures’ “Pretrial Release Violations & Bail Forfeiture” webpage (“Sureties” tab) for more details (note that Rhode Island changed its law in 2017 to grant a 6 month grace period, not reflected on the NCSL chart). ↩

Additionally, a 1996 report by Spurgeon Kennedy and D. Alan Henry summarizes earlier studies showing that bond agents return fewer defendants to custody than law enforcement. Among them: a 1972 study of people released on surety bonds in Los Angeles, which found that 89% of “absconders” were caught by police “with no help from bondsmen” and that bond agents returned defendants on their own in just 6% of cases; a 1991 news report that 9 out of 10 people released on bail bonds in Harris County, Texas were returned by police, not bond agents; and a 1994 survey from Pima County, Ariz., finding that “nearly all absconders were brought back to court by law enforcement.” (See pages 10-11.) ↩

Salt Lake County was the only county with jail data that included this detail in a statewide report, so comparisons with other counties is not possible. However, the Office of the Legislative Auditor General concluded, “While commercial sureties have the authority to return defendants to custody, data provided by Salt Lake County indicates that they are not always exercising this authority. … [T]his data highlights that the cost of returning defendants to custody is often borne by law enforcement, and by extension, taxpayers.” See “A Performance Audit of Utah’s Monetary Bail System” Report to the Utah Legislature No. 2017-01 (2017), pages 36-37. ↩

The National Association of Pretrial Service Agencies offers this commentary alongside Standard 1.4(g), which states, “Pending abolition of compensated sureties, jurisdictions should ensure that responsibility for supervision of defendants released on bond posted by a compensated surety lies with the surety. A judicial officer should not direct a pretrial services agency to provide supervision or other services for a defendant released on surety bond. No defendant released under conditions providing for supervision by the pretrial services agency should be required to have bail posted by a compensated surety.” See “Standards on Pretrial Release,” Third Edition, 2004. ↩

The California Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup (composed of County Superior Court judges) writes in a 2017 report that, while bail agents can request extensions at any time, “The statutes that authorize forfeiture are strictly construed to avoid forfeiture, with specific deadlines for the court to notify the bail agent of a forfeiture. If the court does not meet these deadlines, the bail agent is released from all bond obligations; errors will result in the exoneration of the bond. The bail agent can also file a motion requesting the forfeiture to be vacated, usually due to an oversight by the court or law enforcement.” (See page 33 of “Pretrial Detention Reform: Recommendations to the Chief Justice,” October, 2017.) Similarly, the Utah State Courts committee concluded in its 2015 “Report to the Utah Judicial Council on Pretrial Release and Supervision Practices” that “A large part of the problem described above is the cumbersome statutory process for bail forfeiture. Over the years, … the forfeiture process has grown even more burdensome and difficult with some requirements seemingly imposed only for the purpose of making forfeiture more difficult and therefore less likely to occur.”(See pages 49-50.) In another, single-county example, a 2001 Pinellas County, Fla. audit found that instead of sending notice of forfeiture to the surety company and bond agent within 5 days, as required, the court clerk sent some notices out late, giving the bond agents “a reason for having the estreature [forfeiture] set aside.” (See page 17.) ↩

Florida is a notable exception that does not require any effort on the part of the surety to return the defendant to court in order to get remission of forfeited bond money: According to FL Stat S 903.28 (2019), “… remission shall be granted when the surety did not substantially participate or attempt to participate in the apprehension or surrender of the defendant when the costs of returning the defendant to the jurisdiction of the court have been deducted from the remission and when the delay has not thwarted the proper prosecution of the defendant.” ↩

Oversight of the bail bond industry does not always fall to insurance regulators; in Colorado, for example, the Judicial Branch lists those companies that have failed to pay forfeitures in its “On the Board” report on its website. Violations are still reported to the Division of Insurance, however. See Jones, Brooker & Schnacke (Jefferson County Criminal Justice Planning Unit) (2009), “A Proposal to Improve the Administration of Bail and the Pretrial Process in Colorado’s First Judicial District,” page 82. ↩

Departments of Insurance or similar state regulatory agencies are also typically responsible for ensuring that bail bond companies and their insurers do not write bonds in excess of the amount allowed, which is based on how much collateral they have deposited with the state. (The amount required to secure a given bond amount varies by state. For example, in Colorado, companies must post at least $50,000 in a “cash qualification bond” to the state division of insurance in order to write surety bail bonds in the state. Companies can post a bond worth up to two times the amount posted to the division.) A South Carolina court explains that these minimum requirements are “to protect the State’s enforcement powers by providing collateral to be seized during the estreatment [forfeiture] process. This collateral… giv[es] professional bonding companies a strong incentive to ensure through the use of bounty hunters that those out on bail do not flee the jurisdiction. Without this collateral, the individuals are, in essence, free without any bond.” Nevertheless, state regulators and local authorities often struggle to enforce these bond limits, undermining the ability of the state to hold bond companies and insurers accountable. ↩

In North Carolina, funds from forfeited bonds were supposed to go to the school district. This is an unusual setup: In most states, forfeited bonds go to the state or locality, or a combination of the two. In some cases, these funds are earmarked for specific government funds related to the charges the person faces; in others, the money first covers restitution and other court-imposed fines. ↩

According to some legal and economic analysts, the problems inherent to the commercial bail system are an example of “regulatory capture,” which “occurs when a regulatory agency that is created to act in the public interest, instead advances the commercial or political concerns of special interest groups that dominate an industry or sector the agency is charged with regulating,” according to the CFA Institute. The CFA Institute’s description continues, “When regulatory capture occurs, the interests of firms or political groups are given priority or favor over the interests of the public.” For details about how this concept applies to the commercial bail industry, see James Gordon’s 2021 “Corporate Manipulation of Commercial Bail Regulation” in the Columbia Law Review, Vol. 121., No. 5. ↩

Typically, “opposition” from the industry comes in the form of fear-mongering about increases in crime if more defendants are released pretrial, or released without money on the line. Our analysis of outcomes after pretrial reforms, however, shows that these reforms do not cause an increase in crime. ↩

Jurisdictions that are not ready to immediately end money bail should conduct local and/or state-level analyses of the efficacy and costs of their money bail system (including a cost-benefit analysis), as investigators in New Orleans and Utah have done. ↩

With unsecured bonds, the defendant and/or their co-signer(s) only pay the court the bail amount if the defendant does not appear in court. This is the system Maine uses in lieu of commercial bail. With partially-secured bonds, they pay a portion of the full bail amount to the court (often 10%, which is usually partly or fully refundable), and only pay the rest if the defendant misses their court date(s), if at all. Versions of this system are used in several states that have eliminated commercial bail, including Kentucky, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wisconsin. ↩

This is a recommendation of the County of Santa Clara Bail and Release Work Group’s Final Consensus report on Optimal Pretrial Justice (2016), which points out that “pretrial supervision, which is provided at the County’s expense, may aid the bail bond industry by reducing the risk of forfeiture and increasing the industry’s profit margins.” The Work Group acknowledges that this recommendation does not allow the defendant to recover any premium paid to the bond agent, “it would relieve the defendant of any further bail-related obligations,” such as the liquidation of collateral when a forfeiture occurs. ↩

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Katie Rose Quandt for her invaluable help with the writing of this report, as well as colleagues Leah Wang and Emily Widra for their help with research and map design, and Peter Wagner for helpful editorial guidance. The author also thanks reviewers from Civil Rights Corps for their feedback and illustrator Kevin Pyle for designing a graphic to help explain how the commercial bail industry players, unlike defendants, profit while avoiding accountability. The Prison Policy Initiative thanks the MacArthur Foundation and the Chrest Foundation for making this report possible. Lastly, we thank our individual donors, who give us the resources and the flexibility to quickly turn our insights into new movement resources.

About the author

Wendy Sawyer is the Research Director at the Prison Policy Initiative. Along with helping direct the organization’s research priorities, Wendy is the author (or co-author) of several major reports, including Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, Beyond the Count: A deep dive into state prison populations, Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie, and Arrest, Release, Repeat: How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems. Wendy also frequently publishes briefings on recent data releases, academic research, women’s incarceration, pretrial detention, probation, and more.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. It launched the national fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (a.k.a. prison gerrymandering). Among the Prison Policy Initiative’s hundreds of reports that help the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform, its 2016 report Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time remains one of the most widely-cited reports on the injustice of money bail.

Appendix tables

- A summary of 76 investigations about bail forfeiture and related bail bond problems

- Table of relevant state bail forfeiture statutes to learn how bail forfeiture works in your state

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.