Reaching too far, coming up short:

How large sentencing enhancement zones

miss the mark

by Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner and Leah Sakala

January 27, 2009

Massachusetts requires that certain drug offenses receive a mandatory minimum sentence of two years’ incarceration if the offense occurs within a 1,000 feet of a school. These sentencing enhancement zones were intended to serve as a geographic deterrent in order to protect children from drug activity; identifying specific areas where children gather and driving drug offenders away from them with the threat of an enhanced penalty. These zones are measured in straight lines that extend 1,000 feet from school property, regardless of any obstructions, and the harsher penalties are in effect regardless of whether school is in session, or whether children are present.

A report we released last year, The Geography of Punishment, found that the zone law fails to deter drug activity or protect children while exacerbating racial disparities in incarceration. Putting large numbers of minor offenders behind bars for long periods of time is not an effective use of state resources in good times, but it is particularly unjustifiable when the state is facing an estimated $3.1 billion budget shortfall.[1] Massachusetts cannot afford to preserve a law that fails to protect children while draining the state coffers and incarcerating Latinos and Blacks at a rate 26 to 30 times as frequently as Whites.

This report will explain that because the current zones are so large the law has not worked, cannot work, and has serious negative effects. Shortening the zone distance would make the law more effective. A bill was filed last year by the Joint Committee on the Judiciary to rework the system of strict mandatory minimum sentence for certain drug offenses committed near schools and parks. Among other changes, it proposed to reduce the sentencing enhancement zones to a more effective 100 feet while restoring judges’ discretion in setting appropriate sentences for first-time offenders. This proposal had the potential to save funds while increasing public safety and reducing racial disparities.

The zone law has not worked

Two decades of experience with the zone law have proved that it is not in fact protecting children from drugs. If the law was working to protect children:

- drug usage among children would be falling

- drug arrests would be less frequent inside of the zones than outside them

- that zone law prosecutions would frequently involve situations where children were present.

Unfortunately, no such evidence of success has materialized.

If the sentencing enhancement zone law was reducing children’s access to drugs, drug usage among children would be falling. Government studies, however, show that drug usage among children has stayed relatively stable.[2]

If sentencing enhancement zone laws effectively deterred drug offenders from engaging in illicit drug activity inside the zones, dealers would move just enough in order to avoid the enhanced penalty. As such, one would expect to find more drug activity immediately outside the zones’ borders than inside them. Previous research in Massachusetts and New Jersey shows no evidence of such relocation. William Brownsberger, now a Representative from Belmont, conducted a 2001 study of Massachusetts zone law cases that occurred in the towns of Fall River, New Bedford and Springfield. He discovered that drug dealing was actually denser inside school zones than outside them.[3] It became clear that the zone laws were not deterring drug activity within the specified areas. Both Brownsberger’s study and similar research conducted by the New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing concluded that the magnitude of the 1,000-foot distance causes the law to fail to deter drug dealers from areas around schools. Both suggested that making the zones smaller would make the legislation a more effective deterrent.[4]

If the zone law were an effective way to protect children from drugs, most prosecutions of zone law violations would address incidents of drug sales to minors. Brownsberger’s 2001 study found that more than 99% of zone cases did not involve charges of dealing to minors or using minors in sales.[5] He told the Boston Globe that, “In no cases did we have the classic picture of the pushers standing on the corner offering 5th graders their first introduction to drugs.”[6] Clearly the zone law has not been able to address the problem of children’s involvement in drug activity.

The zone law cannot work

By creating a separate punishment for drug offenses that occur near schools, the legislature wanted to move existing illegal behavior to where children are not present. However, setting the distance at an expansive 1,000 feet ensured that the law could not operate as intended. Large zones may have sounded tougher, but the results were inevitably weak.

1,000-foot zones necessarily fail to act as deterrents because their size makes them difficult for any person to discern and avoid, even if he or she is aware of the harsher zone penalties. If a sentencing enhancement zone covers a large area, such as an urban city, it becomes ineffective and defeats the legislators’ original intent of discouraging drug activity near schools.

The protected 1,000-foot distance from a school is so large and schools are so numerous that zones can cover a large percentage of communities, especially in urban areas. To create an effective safety zone around schools, the area that needs to be protected must be small enough that a person choosing to engage in prohibited drug activities can—to avoid the higher penalty— choose to leave a zone without unintentionally moving into another. In order for them to make this choice, they must have information about where a zone begins and ends. But the zone law includes no provision for identifying the boundaries of a protected area, which in many cases extends far beyond the area that obviously surrounds school property. An offender who is unable to distinguish between zone and non-zone areas is unable to move away from a zone (and thus avoid the harsher punishment) simply because he or she cannot identify a non-zone area to move to. Therefore, zone laws do not move dangerous activities away from children because a person who engages in illegal drug activity has no way of delineating the protected areas where the harsher penalty is in effect.

1,000 feet is too large a distance for two people to communicate or even be easily visible to each other, let alone engage in a drug transaction. In our Geography of Punishment report we set out to determine how far 1,000 feet actually is. As illustrated above, the statute’s requirement that the distance be measured in a straight line, regardless of obstruction, puts many distant areas under the law’s jurisdiction. Our experiment found that a person holding a large white sign under ideal visibility conditions on a perfectly straight and deserted street is reduced to an almost-invisible speck at such a distance. In urban areas with more large obstructions, entire school buildings become invisible at far shorter distances. By not researching an appropriate distance that takes these factors into account, the legislature made the unreasonable assumption that any drug activity that occurs anywhere within 1,000 feet of school property, even within a private home, takes place with the intention of involving schoolchildren in illicit actions.

Our research concluded that 100 feet would be a more effective distance for the zones. Schools are far more likely to be visible at that distance, making it easier for drug offenders to identify and avoid situations where the zone penalties are in effect and children are more likely to be present. We have found that communication from 100 feet away is impossible without shouting, making it a sufficient distance for a law designed to protect children.

The zone law is counter productive

The legislators who created the zone law wanted to protect children from drugs but their failure to pick a rational distance led to a flawed law. The vast majority of harsh sentencing enhancement zone penalties apply to minor offenders who have nothing to do with children and just so happen to be within 1,000 feet of a school. Thus, zone offenders are punished based on their location, not their crime. The 1,000-foot zone law fails to repel drug activity from schools while having a fiscally and socially devastating impact on the state of Massachusetts.

Expensive sentences for minor offenders

The mandatory zone violation penalties deny judges discretion in sentencing and often require them to impose harsh punishments for minor drug offenses, the vast majority of which have nothing to do with children. Mandatory prison sentences are expensive and are paid for by Massachusetts residents’ tax dollars. Just one year of incarceration costs the state $47,679. In fiscal year 2006, the most recent year for which data is available, the zone enhancement law accounted for 796 years of imprisonment on top of the sentences imposed for the underlying drug offense.[7] With the state of Massachusetts currently facing a budget shortfall of $3.1 billion, we cannot afford to keep the ineffective and costly 1,000-foot zone law. Spending exorbitant sums of money to incarcerate a minor offender, who poses no threat to children, just because he or she happened to have committed his or her offense within 1,000 feet of a school, is a misuse of precious funds.

Two-tiered system of justice

Because the zone law disproportionately applies to urban areas, residents of these communities are more likely to receive longer sentences solely because of their location.[8] Our previous study in Hampden County found that an urban resident is five times more likely to reside in a sentencing enhancement zone than a resident of a rural area. The zone law inadvertently creates an unfair two-tier system of justice: a harsher one for dense urban areas with numerous schools and overlapping zones and a milder one for rural and suburban areas, where schools are relatively few and far between.

Punishing urban drug offenders more harshly than rural offenders is not warranted by drug usage patterns in urban and rural schools. Although the federal surveys reports a small disparity in drug use between metropolitan and non-metropolitan adults, urban and rural children aged 12-17 use drugs at the same rates.[9] Despite this fact, the zone law places the burden of the mandatory prison sentences primarily on urban communities.

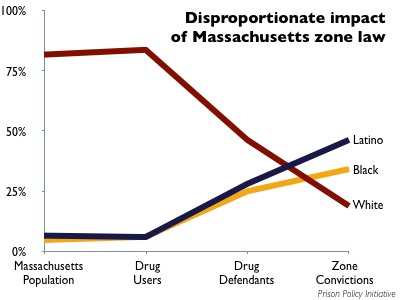

Imposing more mandatory prison sentences on urban drug offenders leads directly to large racial disparities in sentencing because Blacks and Latinos tend to live in urban areas and therefore are more likely to live inside the zones. Our previous report found that 29% of Whites in Hampden County live in zones, but 52% of the Blacks and Latinos do. Latinos are almost twice as likely to live in a sentencing enhancement zone than Whites. As a result, greater numbers of Blacks and Latinos are charged with zone violations than Whites who commit the same drug offenses.[10] New data shows that the discriminatory effect that the zone law produces is found throughout the entire state. Blacks and Latinos are less than 13% of the state, but together account for 90% of the zone convictions. Compared to White residents of Massachusetts, Blacks are 26 times as likely to be convicted and receive a mandatory sentencing enhancement zone sentence, and Latinos are 30 times as likely. The geographic disparity that is inherent in this law’s application creates an extreme racial disparity in convictions.

Figure 1. While Whites, Blacks and Latinos in Massachusetts use drugs in rough proportion to their population, Blacks and Latinos are disproportionately arrested and charged for drug law violations. The operation of the zone law magnifies this inequality. Whites are the majority of the state but only a small minority of the zone convictions. Blacks and Latinos are a minority of the state’s population and drug users, but received an overwhelming majority of the 796 years of prison time imposed for zone offenses last year.

The harsher penalties that Black and Latino offenders receive under the zone law is unwarranted by statistics on drug use by race. Although Blacks, Whites, and Latinos use illegal drugs at approximately the same rate,[11] the poor construction of the zone law causes minority populations to disproportionately bear the burden of the harsher sentences (See Figure 1).

Conclusion

Despite the good intentions of the zone law, it has become clear that the 1,000-foot zone law is an ineffective way to protect children and is actually doing more harm than good. An expensive burden on the state, the current discriminatory zone penalties are not deterring drug offenses from school areas and are instead unfairly punishing urban residents, Blacks and Latinos.

But legislators have already made progress towards remedying the flaws in the current zone law. At the end of last year’s legislative session, the Joint Committee on the Judiciary introduced a major reform of the zone law that would have protected children and reduced many of the law’s inequities. Included with a larger criminal justice package (H. 5004), the proposed zone law would have exempted first time drug offenders from the harsh mandatory minimum and set the maximum penalty for a first time violation of the zone law to 2 years. Subsequent violations of the new zone law would remain the same: 2 to 15 years. But most significantly, the bill addressed the decades-old flaw in the zone law that we have identified in our reports: The current zone is too large.

Last year’s H. 5004 proposed to reduce the radius of the zones to 100 feet.[12] Experiments conducted for our earlier report, The Geography of Punishment, confirmed that 100 feet is an appropriate distance for an effective geographically based deterrent. This distance would also reduce much of the social and fiscal harm caused by the current 1,000-foot law.

With the zone law at 100ft, the law could in fact work as an effective deterrent to steer drug activity away from schools. Potential drug offenders who wish to avoid the higher zone penalties will more effectively be deterred by smaller zones as it is far easier to identify a school from 100 feet away than from 1,000 feet away. Smaller zones would cover less area in urban communities and offenders would be better able to steer clear of situations involving children. As we demonstrated in our previous report, communication from 100 feet away is only possible by shouting and drug transactions would be virtually impossible from such a distance. This bill would more effectively protect children from drug activity outside school buildings.

Unlike the current law, under which most drug offenses in the zones have little connection with minors, the legislature would have better grounds to assume that offenses within 100 feet of a school pose a risk where the enhanced penalty would be warranted. Far fewer Massachusetts tax dollars would be spent incarcerating minor offenders who had nothing to do with children, and our resources would instead be devoted to improving public safety by effectively addressing serious threats to children’s wellbeing.

About the authors

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative documents the impact of mass incarceration on individuals, communities, and the national welfare. We produce accessible and innovative research to empower the public to participate in improving criminal justice policy. In 2008, we released The Geography of Punishment: How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children. For more information about our work, see our website http://www.prisonpolicy.org.

Aleks Kajstura is a graduate of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law and the President of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Peter Wagner is an attorney and Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Leah Sakala is a student at Smith College.

Acknowledgements

This report was produced with the generous support of dozens of individual donors and a grant from the Drug Policy Alliance.

Endnotes

[1] Elizabeth McNichol and Iris J.Lav, State Budget Troubles Worsen, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated December 23, 2008, table 3

[2] Massachusetts Department of Education, 2005 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. The 2003 version of this survey contains an additional survey year, 1993, further confirming the stability of the numbers.

[3] William N. Brownsberger & Susan Aromaa, An Empirical Study of the School Zone Law in Three Cities in Massachusetts, p. 20 (Join Together and Boston University School of Public Health) 2001.

[4] Brownsberger suggests a distance of 100-200 feet and the New Jersey Commission to Review Sentencing recommends 200 feet. William N. Brownsberger & Susan Aromaa, An Empirical Study of the School Zone Law in Three Cities in Massachusetts, p. 22 (Join Together and Boston University School of Public Health) 2001 and Report on New Jersey's Drug Free Zone Crimes & Proposal For Reform p. 29 (The New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing) 2006

[5] William N. Brownsberger & Susan Aromaa, An Empirical Study of the School Zone Law in Three Cities in Massachusetts, p. 22 (Join Together and Boston University School of Public Health) 2001.

[6] Anand Vaishnav, Drug-Free Zones Questioned, Study Says Law Failed to Stop Sale Near Schools, The Boston Globe, July 19, 2001, at B4.

[7] According to the Massachusetts Sentencing Commission, in fiscal year 2006, 293 people were sentenced to two-year mandatory minimum sentences in Houses of Correction and 84 people were sentenced to two-and-a-half year prison sentences. Multiplying the number of people sentenced by the sentence lengths allows us to estimate the number of people incarcerated on any one date for zone offenses. The Massachusetts Department of Corrections estimates that it costs $47,678.67 to incarcerate one person for a year.

[8] In his Massachusetts study, Brownsberger found that most drug dealers are arrested near their homes, and that 73% of the defendants in enhancement zone cases lived within a zone. William N. Brownsberger & Susan Aromaa, An Empirical Study of the School Zone Law in Three Cities in Massachusetts, pp. 19-20 (Join Together and Boston University School of Public Health) 2001.

[9] The NHSDA Report: Illicit Drug Use In Metropolitan And Non-Metropolitan Areas, table 2 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) 2002.

[10] U.S. Census 2000 and Massachusetts Sentencing Commission, Survey of Sentencing Practices, Fiscal Year 2006, Table 39.

[11] Department of Health And Human Services, Results From The 2004 National Survey On Drug Use And Health: National Findings, p. 18 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)) 2005.

[12] H5004 §21 (link no longer available) introduced July 23, 2008