For the poorest people in prison, it’s a struggle to access even basic necessities

Our survey of all 50 states and the BOP reveals that prisons make it hard for people to qualify as indigent—and even those who do qualify receive limited resources.

by Tiana Herring, November 18, 2021

Many people in prison struggle to purchase basic hygiene supplies, stamps, and other necessities of incarcerated life—thanks in part to the low wages they made before entering prison1 and the mere pennies they earn working behind bars. Most prison systems claim to provide assistance to people who are extremely poor (or, in correctional policy terms, “indigent”). However, our new survey reveals that these “indigence policies” are extremely limited—both in who they help, and the amount of assistance provided.

We found that in almost every state2 and the federal prison system, incarcerated people must maintain extremely low balances in their “inmate trust funds”3 before receiving any help with essential items like soap and stamps. And being deemed indigent is only half of the battle, as many states provide very few resources even to those who do qualify. What’s more, in 18 states, the assistance given to indigent people is actually treated as a loan they must repay if their account balance ever goes up, meaning that people are required to go into debt for access to basic necessities.

We gathered information on indigence policies in all 50 states and the federal Bureau of Prisons by looking through state departments of corrections’ websites and contacting public information officers in each system. Here, we offer answers to two questions:

- How is indigence is defined in each state?

- What items or services are supposed to be provided to indigent incarcerated people, according to state policies?

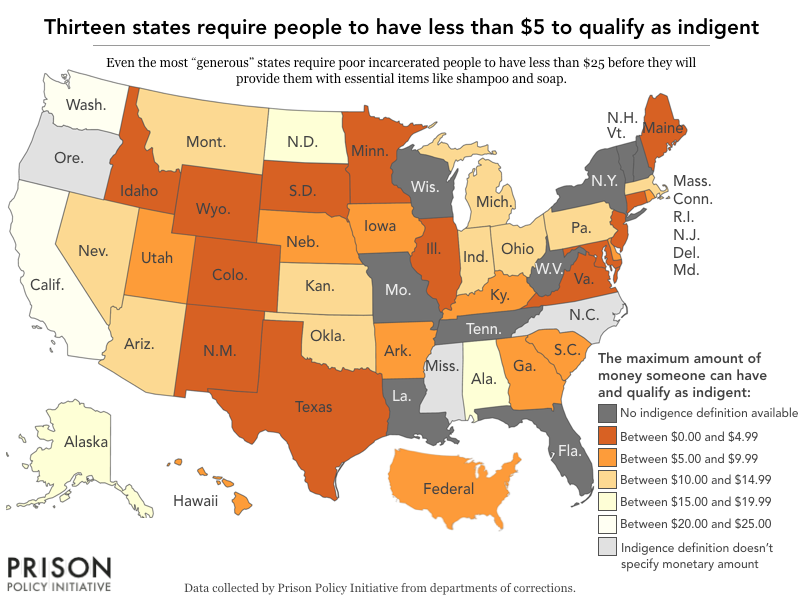

Most states have very narrow definitions of who qualifies as “indigent”

We were able to find a definition for indigence in 41 states and the federal Bureau of Prisons. The remaining nine states did not have easily accessible definitions online, and were not able to provide us with the requested information when asked. The lack of transparency is disappointing, and makes it difficult to hold prisons accountable for doing the bare minimum to support the poorest incarcerated people. Worse, this inability to produce policy information may be an indication that some states do not have indigence policies, meaning extremely poor incarcerated people in these states might not receive any assistance at all.

Every single department of corrections with an indigence policy requires people to have very little money before they can qualify. The monetary thresholds for indigence status range from a low of $0 (meaning that people with $1 to their name would not be considered indigent) to a maximum of $25. Over half of states have their limits set between $0 and $10. Additionally, most states require that people keep these low balances for at least a month before qualifying. If someone does get money added to their account that exceeds the indigence limit, they lose their indigence status and have to wait before they can be considered indigent again. In New Mexico, for example, an incarcerated person must have $0 in their account for a month before they qualify as indigent. Going so long with such low account balances means that people are surviving on severely limited access to food4 and basic necessities like toilet paper. While 30 days was the most common wait time – and certainly too long to have to wait for soap and envelopes to write home – Alabama, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Utah all require people to wait even longer, from 45 to 90 days.5

These arbitrary limits on the amount of money people can have means that people can lose their “indigence” status—and therefore their access to necessary supplies—just because they received a small deposit from a family member or for working a prison job. Many indigence policies specifically prohibit deposits and income of any amount in their definitions. For example, an incarcerated person in Maryland making 15 cents an hour for their labor can’t qualify for indigence status; while $0.15 an hour will hardly make someone rich, people are not allowed to work and receive free access to indigent supplies. These policies often ignore that many incarcerated people have automatic deductions taken from any money deposited into their accounts, including for fines and fees, involuntary savings funds, or repaying the department of corrections for items they received previously while considered indigent.

We also found that four states put additional work-related requirements on who can qualify for indigence, by limiting the status to those who are incapable of working, are “involuntarily unemployed,” or are actively seeking work.

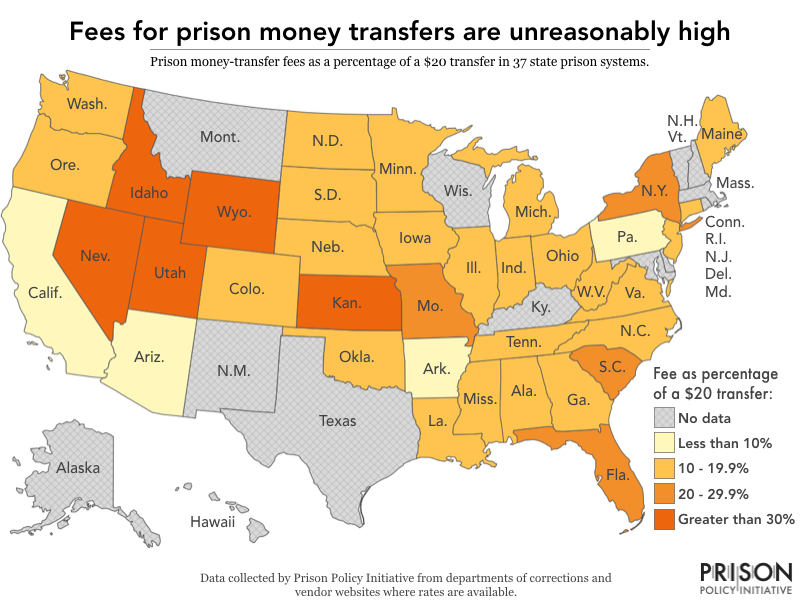

The fact that free basic supplies are provided only to the poorest people—and not to all incarcerated people for free by default—fits with correctional trends of shifting the costs of incarceration onto incarcerated people and their families, as also evidenced through the rise of paid services like tablets and phone calls.

The services offered to indigent people vary from state to state, but they are always very limited

The most common items provided to indigent incarcerated people are hygiene kits6 and supplies for sending a limited number of letters to loved ones; the number of free letters allowed range from one per month in Ohio to seven per week in Maryland. Legal mail is also mentioned in many policies, though departments of corrections are more likely to require repayment for these mailings. In some states, people have to choose between using their mail supplies for personal or legal mail, as they aren’t always considered separate services.

Eighteen states require indigent people to pay the department of corrections back for at least some of the services they receive while deemed indigent. In at least seven states, correctional agencies don’t appear to offer any services or supplies for free without the expectation of repayment. The Department of Corrections in Washington State, for example, covers the cost of mailing up to 10 letters per month for indigent incarcerated people. However, if the indigent person ever loses their indigence status, the department will recoup the costs for any letters previously mailed for free by deducting money from their “inmate trust accounts.” In states with repayment policies, the only way for the poorest incarcerated people to stay out of debt is to simply not write letters to their families, despite the fact that communication is crucial for maintaining family ties and increasing the chance of success upon release.

Every prison system can—and should—do more

Every indigence policy we looked at could be improved, but some states have implemented a few decent practices (at no cost to incarcerated people or their families) that others could consider adopting:

- Seven states allow indigent incarcerated people and their families the opportunity—though often very limited—to communicate via phone calls, video calls, email, or texts free of charge.7

- Seven states clearly state that feminine hygiene products are provided to those who need them, free of charge.8

- Seven states specify that toilet paper is provided to indigent incarcerated people for free.9

- New Jersey provides indigent incarcerated people with a $15 monthly allowance for commissary, which is important for access to food and basic necessities.

- California’s code of regulations prohibits charging indigent incarcerated people for mailing services they received while considered indigent (including the cost of materials, copying, and postage) if they lose indigent status.

Stringent indigence policies punish the poorest people in prison by severely limiting the amount of money people can have and still receive free services, dictating how they can spend the little money they do have, and making them wait weeks in extreme poverty before offering help. All incarcerated people deserve, at minimum, access to hygiene items and ways to communicate with loved ones without having to take on even more debt.

Footnotes

-

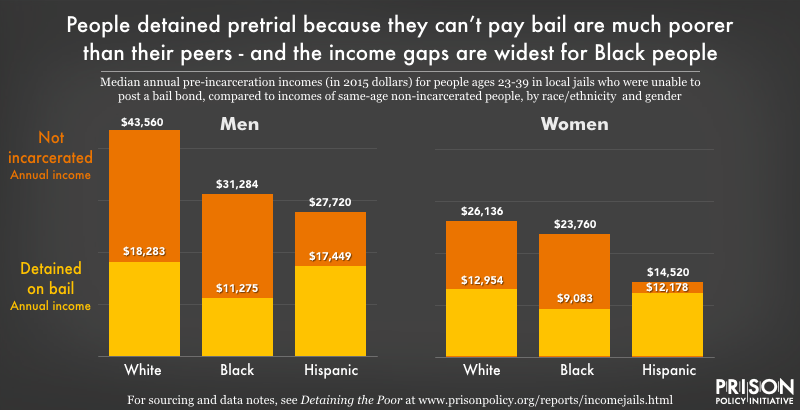

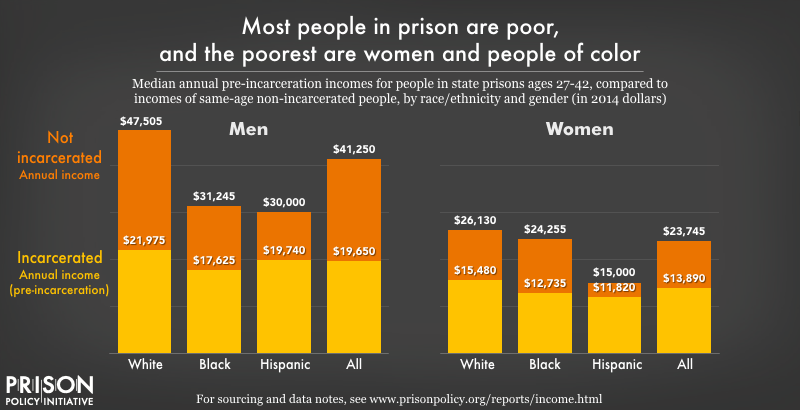

Incarcerated people had a median annual income prior to incarceration that was 41% lower than non-incarcerated people of similar ages. Unfortunately, this national data is not available for individual states. ↩

-

All states that have indigency policies require unreasonably low balances, but nine states did not share them with us, and therefore may not provide any support to people unable to purchase necessities. ↩

-

The term “inmate trust fund” – also called a “trust account”—is a term of art in the correctional sector, referring to a pooled bank account that holds funds for incarcerated people whose individual balances are sometimes treated as subaccounts. The term “trust” is used because the correctional facility typically holds the account as trustee, for the benefit of the individual beneficiaries (or subaccount holders). ↩

-

Prison cafeterias often serve small portions of unappealing, nutrient deficient foods. As a result, most of the money people spend in the commissary goes toward purchasing extra food. Formerly incarcerated people who had little outside financial support report that they experienced constant hunger and a variety of health issues as a result. ↩

-

While some departments of corrections may feel wait times are necessary to prevent people from manipulating account balances to receive indigence status, long wait times create unnecessary delays in needed assistance. ↩

-

What’s included in hygiene kits varies by state but generally they include soap, shampoo, a toothbrush, toothpaste, and shaving equipment. ↩

-

These states include Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, and Wisconsin. ↩

-

These states include Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. ↩

-

These states include California, Colorado, Idaho, Nebraska, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. ↩

Appendix

| State | How is indigence defined? | What is provided for free to the indigent? | Does the DOC expect repayment? If so, for what? | Relevant policy numbers, documents, or other sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | “An inmate who is found to be financially unable to pay the co-pay and so is allowed to proceed in forma pauperis. For the assessment of medical co-pay charges, an inmate who maintains less than an average daily balance of twenty-dollars ($20.00) on his/her ITF account for the past ninety (90) days AND who has not received gross receipts totaling more than one hundred dollars ($100.00) during the past ninety (90) days will be considered indigent.” | Medical co-pays. | No | AR-703 and AR-703-1 |

| Alaska | “A prisoner who has less than $20 presently available in his or her account and who has had no more than $50 in his or her account during the preceding 30 days. A prisoner with more than $50 in his or her account during the preceding 30 days will still be considered indigent if no more than $50 remained after mandatory deductions (restitution, fines, child support enforcement orders, violent crime compensation payments, or civil judgments, e.g.) or deductions made for educational materials or courses, counseling, or health care.” | Mail up to 5 pieces of mail per week, weighing up to two pounds each; each facility has a system allowing indigent people to obtain hygiene items through commissary. | Yes. Costs related to legal copies and photocopies of personal materials need to be paid back. | 806.02, 808.12, and 810.03 |

| Arizona | “One whose account balance is $12.00 or less and has not exceeded this amount during the previous 30 days.” | Mail up to three letters per week by first class mail; healthcare supplies. | No. | Constituent Services Informational Handbook and ADCRR Glossary of Terms |

| Arkansas | “Must be at the unit for 30 days, have less than $10 on account plus have received less than $10 on account in the immediate preceding 30 days.” | People considered indigent receive an unspecified amount of money every 30 days that can be used to purchase commissary items. | No. | Inmate Handbook |

| California | “An inmate in a state prison who has maintained an inmate trust account with $25 or less for 30 consecutive days.” | Products for washing hands, bathing, oral hygiene, and other personal hygiene including but not limited to: soap, toothpaste or toothpowder, toothbrush, and toilet paper; writing paper, envelopes, a writing implement, and postage required for five 1-ounce first-class letters per week; an unspecified number of envelopes (metered) if housed in a behavioral management unit; notarized documents free of charge; necessary duplication of printed forms and other written or typed materials, special paper, envelopes, and postage for mailing to the courts; may receive donated, working tv sets; free unlimited mail to any court or attorney general’s office; indigent inmates shall have property shipped to an address of their choosing at the CDCR’s expense; for third level appeals, indigent inmates shall not be required to divide their appeal into separate mailings to conform to indigent mail weight restrictions; free copying and postage of legal documents required by the court, plus one copy for the opposing party and one copy for the inmate’s records. | Yes. If an indigent incarcerated person wants funds for a hobby they can request a handicraft loan. The loan will be considered uncollectable if they are paroled or discharged from CDCR. | AB 2533, NCR 20-02, an email exchange with CDCR on 10/8/2021, and the following policies in the CDCR Operations Manual: 14010.21, 52051.17, 54010.5, 54010.5.2, 54010.5.3, 54030.13.3, 54100.6, 62060.7, and 101050.4.4. |

| Colorado | “An offender with no funds or source of income.” | Mail one letter per week, contingent upon funding; basic hygiene kits which include soap, toilet paper, toothbrush, toothpaste, denture cleaner and adhesives, and shaving equipment; if the administrative head deems there are compelling circumstances, they can ask the state to pay for a phone call which will go on their chronological record and be supervised; may place collect calls. | No. | 850.11 and an email exchange with CDOC on 10/26/2021. |

| Connecticut | “Less than $5.00 in their account for the previous 90 days.” | Personal hygiene items including shampoo, soap, toothpaste, and toothbrush, comb, disposable razor, sanitary napkins/tampons; underwear and footwear; writing materials including writing instrument and up to 20 sheets of paper for courts and attorneys per month; mail two social letters per week and five privileged letters per month; sick call fees. | No. | Family and Friends Handbook, Inmate Handbooks, and an email exchange with CT DOC on 10/12/2021. |

| Delaware | “An indigent offender has an established pattern of insufficient funds, in his/her Trust Fund Account, averaging less than $10 per day in a rolling 30-day period, with which to pay for supplies such as basic personal hygiene items, writing materials, postage, and legal copies.” | None. | Yes. Indigent people must repay the costs of hygiene items, writing materials, postage, legal copies, and release clothing and gate money. The Department of Corrections should be reimbursed when capable, and a negative balance remains on books until satisfied, even post release. (source. DE DOC) | Email exchange with DEDOC on 10/29/2021. |

| Federal | “An inmate without funds (indigent inmate) is an inmate who has not had a trust fund account balance of $6.00 for the past 30 days.” | No health care service fee; given over the counter medications at the institution pharmacy; provided oral hygiene products; if transferring from one facility to another, and they own something that can be transferred, the facility may cover the cost of stamps to complete the transfer. | No. | P6031.02, P6541.02, 6400.03, and 5800.18 |

| Florida | Indigence definition not available. | Paper and writing utensils to prepare legal papers. | No. | Rule 33-601.800 |

| Georgia | “An offender may be classified as indigent for purposes of this SOP, if account records indicate that their Inmate Trust Account has less than ten dollars ($10.00) on the date of the offender’s request to use funds. Frozen funds will not be counted for these purposes.” | None. | Yes. Costs incurred for postage and correspondence materials must be paid back. | 406.19 and an email exchange with GDC on 10/11/2021. |

| Hawaii | “An inmate with less than $10.00 of income in her/her spendable account at the time of his/her request.” | Postage and supplies for three privileged letters per week, and one official or personal letter per week; one phone call per week. | Yes. Services such as court actions requiring filing fees and notary services will be paid for but debited to the inmate account and deducted when moneys are entered into their inmate trust account. | COR.15.02 and an email exchange with Hawaii DPS on 10/8/2021. |

| Idaho | “An inmate who has been housed at an IDOC correctional facility (including a contract facility) for 30 consecutive days and whose trust account has a balance of less than $0.15 and has had no deposits for 30 consecutive days. If the inmate is paroled or released and returns to the IDOC as an inmate, the 30-day clock starts over. If the inmate is transported to another facility, hospital, county jail, or out of state the inmate retains indigent status upon return to an IDOC facility provided the inmate did not receive any deposits in the meantime.” | Hygiene items issued once per week upon request, including soap, toilet paper, toothbrush, toothpaste, and a disposable razor; materials (4 sheets of paper, one envelope, a writing instrument) and postage for one personal letter per week; one additional mail envelope per week for confidential correspondence; envelopes, postage, and photocopies for legal mail. Materials for legal mail include 25 sheets of paper, envelopes, and black ink pen; If diagnosed with gender dysphoria, state will issue appropriate undergarments; eyeglass replacements if necessary; over the counter medication if approved by health care provider. | No. | 402.02.01.001, 306.02.01.001, and an email exchange with IDOC on 10/14/2021. |

| Illinois | Illinois had three different definitions in the same document. 1. “Anyone not receiving offender pay due to restitution owed to the court, corrections, etc.” 2. “no money on his account, no state pay and no money coming in” 3. (for medical care) “one who’s Trust Fund balance [does not] exceed $20.00 on the date of service, or at any time with the preceding 30 days prior to service.” | Hygiene kit including soap, toothpaste, and toothbrush; waived fee processing fee for accessing criminal history record; medical copays. | No. | Orientation Manual |

| Indiana | “An offender who has a Trust Fund account balance of less than fifteen dollars ($15.00) on the day of request and has not had a total of more than fifteen dollars ($15.00) credited to the trust fund account in the preceding thirty (30) days.” | Hygiene kit including toothbrush, toothpaste or powder, denture cleaner and adhesive, comb, bath soap, deodorant (or soap with deodorant), shampoo, and shaving supplies; mailing legal documents; copies of legal documents. | No. | 02-01-104 and 00-01-102 |

| Iowa | “An offender who has less than $6.00 in their account, has not exceeded a $6.00 balance in their account in the last thirty days, and whose net revenue has not exceeded $6 in the last thirty days.” | Up to $3.50 credit to purchase supplies for legal correspondence; certain hygiene items, to be determined by each facility. | No. | AD-GA-16, IO-OR-05, and AD-FM-11 |

| Kansas | “An inmate whose inmate bank account during the previous month has a cumulative spendable amount of less than $12.00. The cumulative spendable amount shall be determined by adding all deposits made during the month to the beginning account balance and subtracting fines, fees, restitution, garnishments, forced savings, and payments or encumbrances for court filing fees applied during the month. Amounts voluntarily withdrawn from the inmate’s account shall not be subtracted from the sum of the beginning balance and deposits.” | An electric fan If they’re in a unit without appropriate circulation; basic personal hygiene items including toothbrush, toothpaste, razor, comb or pick, and soap; a pencil, writing paper, envelopes, and postage for four first class, one ounce, domestic letters per month. | No. | 12-127, 12-128A, and Inmate Trust Account FAQs |

| Kentucky | “An inmate who has maintained a balance in his inmate account and media account for a combined total of $5.00 or less for thirty (30) days prior to requesting indigent status.” | Postage and stationery sufficient to send two letters weighing one ounce or less per week; “reasonable amounts” of legal supplies, postage, and copying services as necessary. | No. | 14.4, 15.7, and 16.2. |

| Louisiana | Indigence definition not available. | Unknown. | Unknown. | None. |

| Maine | “Has a zero balance in their account at the facility and has no funds in a personal savings account or investment at the time of making a request for free privileged mail, free legal photocopies, or free basic hygiene.” | Writing supplies and postage for at least four, one ounce, first class letters per week; basic hygiene items; writing supplies and postage for the purpose of corresponding with attorneys, courts, and the MDOC inspection division (no limit); commissary items that are authorized by the administrator; free photocopies of court filings; if they have access to tablets they are given 20 free text messages per week. | Yes. A resident with no more than $10 dollars is provided phone call minutes of up to $2.50 per week (the phone charge is 9 cents a minute) and must pay this back if they become able to within six months. For medical care, there is a statute which requires a $5.00 co-pay for some services. If a resident has less than $15, this co-pay is waived, and it must be paid back if they become able to within six months. | Detention and Correctional Standards for Maine Counties and Municipalities and an email exchange with MDOC on 10/14/2021. |

| Maryland | “An inmate who, within the previous 2 weeks, has not received pay for an assignment in work or school, and who has less than $2 in his or her spending account, or an inmate received within the previous 2 weeks who has not had $2 in his or her spending account.” | Hygiene items including a toothbrush, toothpaste, comb, soap, shaving cream, disposable razor, deodorant, and shampoo; writing instrument, paper, envelopes, and postage for seven letters per week | No. | COMAR 12.02.20.01, OPS.250.0001, PATX.175-0002, and an email exchange with Maryland DPSCS on 10/8/2021. |

| Massachusetts | “(a) At the time of the request, the inmate has, in all accounts to which he or she has access, a total amount less than or equal to $10.00 plus the cost or fees sought to be waived; and (b) At no time for the 60 days immediately preceding said request, have the inmate’s accounts contained more than $10.00 plus the cost or fees sought to be waived. (e.g. request to waiver $5.00 on July 1, 2015; indigent if, at no time since May 1, 2015, total in accounts has been more than $15.00). In addition to 103 CMR 481.05. Indigent Inmate(a) or (b), the Superintendent may in his or her discretion, designate an inmate as indigent if the inmate has less than $2.00 in his or her account at the time of the request, or in other circumstances as he or she deems appropriate.” | Three one-ounce, first class letters per week; unlimited number of letters of any weight to any court official. | No. | 103 CMR 481.00 |

| Michigan | “1. The prisoner’s available account balance (on the first day of the calendar month preceding application) plus gross receipts (total receipts received in the calendar month preceding application) did not equal or exceeded $11.00 except as follows. a. If funds are received that are designated for release planning or for medical or educational expenses, those funds shall not be used in the calculation. b. If there is a hold placed on funds that are subject to a hearing (e.g., Health Care co-pay, restitution, error correct), those funds would not be included in the prisoner’s beginning available account balance. c. If the prisoner is subject to IRS federal tax withholding, then receipts shall be determined before the tax has been withheld. AND 2. The prisoner has no known cashable savings bonds.” | None. | Yes. Indigent people will be provided with a loan (equal to $11.00 minus whatever they have in their account) to be able to purchase health care products, over the counter personal care products, and hygiene products. They will also be loaned the amount necessary for up to 10 stamps per month. | 04.02.120 |

| Minnesota | “An offender who currently has less than $1.00 in the spending account, less than $1.00 in the voluntary savings account, has not made any canteen purchases for the past 14 days and has not had any withdrawal requests processed for the past 14 days or has not transferred to another facility within the past 14 days.” | Materials for mailing services including one pen as needed and 35 sheets of writing paper per week; one first class (maximum weight 13 ounces) postage-paid large (9.5″ x 12.5″) envelope per week; two first class (maximum weight 13 ounces) postage paid business size envelopes per week (up to 4″ x 9.5″); A total of 35 sheets of legal and medical record photocopies per week; One over the counter medication from canteen per week; Laundry soap and personal care items including such examples as toothbrush, toothpaste, razor, comb, deodorant, soap, shampoo, dental floss loops, and (if wearing dentures) denture cleaner and medically-authorized adhesive as allowed on the MINNCOR restricted centralized canteen catalog. | Yes. If someone can’t pay for medical care or is indigent, the department of corrections will either find a way to get payment later or waive the fees. | 300.140 and the Medical and Nursing Services Fact Sheet |

| Mississippi | Medical Definition: “not having sufficient funds to pay the assessed fee at the time of receipt of health-care services.” Mail Definition: “An indigent inmate is defined as one who is without funds and has maintained the balance of less than a first class stamp or less for 30 consecutive days preceding the requested mailing.” | None. | Yes. Indigent people are required to pay health care related costs at a later time. Similarly, indigent people can mail legal documents after proving it’s for pending litigation but the department of corrections will give them a negative balance in their account for the postage. | Inmate Handbook |

| Missouri | Indigence definition not available. | Unknown. | Unknown. | None. |

| Montana | “1. The offender has received or spent less than $15 in the previous month. 2. The offender has less than $15 in his or her account at the previous month’s end. 3. The offender has less than $15 on his or her account at the time of verification. 4. The request form must be filled out completely and clearly written. 5. The facility resident account representative must receive the request no later than the second business day of each month.” | An indigent inmate package which includes hygiene items, paper, envelopes, writing instruments, and postage (for writing and mailing legal documents). | No. | DOC 4.1.4, DOC 3.3.6, and an email exchange with MDOC on 11/3/2021. |

| Nebraska | “Those who have not had a balance of $10.00 or more in their institutional and/or regular savings account during the past thirty days.” | Five first-class, U.S. postage embossed envelopes per month or the equivalent in metered mail to send letters in order to maintain community ties; hygiene products including soap, shampoo, toothbrush, toothpaste or powder, a comb, toilet paper, special hygiene items for female inmates, shaving equipment upon request, denture cleaner and adhesive; each month indigent incarcerated people can choose either five stamps for mail or $2.50 debit calling time. | No. | 205.01, 205.03, and 111.01 |

| Nevada | “Inmates whose trust account balance is $10 or less for the entire previous month.” | legal supplies (white bond paper, paper, carbon paper, envelopes, pens, 1 fire proof box) once a month; one blue pen per month; two envelopes and four sheets of paper per week. | Yes. Indigent people can use as much legal postage as they need but will have to pay it back. Co-pays and other services for which inmates cannot pay must be paid back eventually. | AR 722, NDOC Glossary, and an email exchange with NDOC on 10/13/2021. |

| New Hampshire | Indigence definition not available. | Limited amounts of typing paper and envelopes for use only on their case. | No. | Manual for the Guidance of Inmates |

| New Jersey | “An inmate who has no funds in his or her account and is not able to earn inmate wages due to prolonged illness or any other uncontrollable circumstances, and who has been verified as having no outside source from which to obtain funds.” | Photocopying services, including legal materials; personal hygiene items including soap, toothbrush, toothpaste or powder, a comb, toilet paper, shaving equipment, and products for special hygiene needs of females; $15 per month for commissary; they’re not charged for services such as legal mail, legal copies, medical copays, etc. | No. | 10A-31, Inmate Handbook, and an email exchange with NJDOC on 10/12/2021. |

| New Mexico | “Their trust fund account has been without funds or activity for a period of one (1) month prior to his/her request for such items.” | State-issued underwear, shoes, uniforms, blankets, pillows, towels, etc.; two first class letters per week; a reasonable amount of postage for legal purposes; free paper and pens; one free call per week and one free video call per week; two hygiene packs per week that include toothbrush, toothpaste, shampoo, and deodorant and they can request more if needed. | No. | CD-151200, CD-151100, CD-150200, and a phone call with NMCD on 10/14/2021. |

| New York | Indigence definition not available. | Unknown. | Yes. Costs incurred for legal mail postage must be paid back. | 2788 |

| North Carolina | “An offender is considered indigent if they have no money to purchase basic hygiene items such as soap or deodorant.” | Up to 10 stamps per month for 1-ounce personal letters. This stamp limit does not apply to mail relating to legal matters; basic hygiene items every 30 days; upon release, they receive $45 in gate money if they have served two consecutive years of a felony sentence; upon release, they are given the cost of a bus ticket if they do not have at least 5 times the cost of the ticket in their offender banking account on their release; prior to release, DOC helps them with opening a bank account, visiting the local housing authority to find a place to live, obtain a driver’s license from DMV or birth certificate from the NC Vital Records Office. They also try to transfer them closer to home when possible so family can pick them up. | No. | Handbook for Family and Friends of Offenders and an email exchange with NCDPS on 10/8/2021. |

| North Dakota | “You must have received $15.00 or less of spendable money each month. This includes spending balances carried over from the previous month. You must be actively seeking a job and cannot have quit a job, refused to work, or have been fired from a job or work assignment within the past 30 days.” | Up to $4 credit per month for legal copies, legal postage, and regular or personal postage; basic hygiene; writing materials; DOC may waive the copay for oral surgery; costs covered for glasses every two years; two free 15 minute phone calls per month to contact their children and two free video visitation sessions per month to individuals actively working toward family reunification within their case plan; hearing aid batteries (hearing aids are given to anyone who needs them); if PCP approves, they may be provided over the counter medication. | Yes. If the $4 credit for legal copies, legal postage, and regular or personal postage is exhausted, money is taken from their “release aid account.” Any money spent beyond that available balance is recorded as a debt. | Inmate Handbook and an email exchange with NDDOCR on 10/8/2021. |

| Ohio | “An inmate is considered indigent if, during the 30 days immediately preceding the request, the inmate has earned or received less than $12.00 and, if the inmate’s account balance has not exceeded $12.00 at any time during the thirty (30) days immediately preceding the request. In the case of an inmate who has been incarcerated for less than thirty (30) days, the inmate is considered indigent if the inmate’s account balance has not exceeded $12.00 at any time during the period of incarceration.” | Legal kit including two large manilla envelopes, one black ink pen, five sheets of carbon paper, 40 sheets of white bond or copy paper, and one white writing-paper tablet from the library every 30 days; first class mail to courts of law; one free stamped envelope per month; hygiene kit provided weekly that includes a toothbrush, toothpaste, dental floss, comb or pick, razor, deodorant, and 2 boxes sanitary napkins and/or tampons for people entering women facilities; Eight free electronic mail stamps per month for outbound email only, which includes videograms and attachments. | No. | 59-LEG-01, 61-PRP-02, 75-MAL-01, and an email exchange with ODRC on 10/8/2021. |

| Oklahoma | “An inmate is considered indigent if the total of their end of day available balance and all voluntary withdrawals for the last 30 days does not exceed $10.50. a. Any disbursements, cash draws, canteen sales or similar transactions will count as a “voluntary” except disbursements for birth certificates. b. Co-pays, court costs, fines, fees, institutional debt and similar transactions will not count towards the $10.50 “voluntary” withdrawals. The available balance is checked for being over the $10.50 limit after these collections are made. If co-pays, court costs, fines, fees, institutional debt, and similar mandatory collections collect all but $10.50 of the funds that an inmate receives in their available balance and the inmate would otherwise be indigent the inmate is still indigent.” | Two one-ounce privileged or non-privileged letters per week; personal hygiene items including soap, shampoo, toothbrush, toothpaste or powder, denture cleaner and adhesive, comb, toilet paper, razors, sanitary napkins/tampons (for females), and deodorant; if someone has a fan or tv confiscated it may be given to an indigent person instead of being auctioned. | No. | OP-120230 and OP-030117 |

| Oregon | “Two categories of inmates will qualify for indigent status. (a) A Priority Legal User who is without sufficient funds in the inmate’s trust account to pay for the costs of necessary supplies, photocopies and mailing services at the time of the request will be provided necessary supplies, photocopies, and mailing services notwithstanding the inmate’s indigent status in accordance with these rules. (b) A General Legal User with an imminent Court Deadline who can demonstrate the inability to acquire funds or purchase necessary supplies or mailing services within the court deadline will be provided necessary supplies, photocopies and mailing services notwithstanding the inmate’s indigent status in accordance with these rules.” | Additional storage units for storage of legal material in their living quarters; envelopes for necessary court filings. | Yes. Indigent people may be provided with photocopies, supplies, and mailing services but their accounts will be charged and they will have to pay the state back. The same is true for those requesting copies of their own records (medical, dental, psychiatric, etc.) | 291-139-0180, 291-117-0100, 291-139-0130, and 291-037-0020 |

| Pennsylvania | “An inmate for whom the combined balances of his/her facility account and any other accounts are $10 or less at all times during the 30 days preceding the date on which the inmate submits a request to the person designated by the Facility Manager/designee. An inmate who refuses available work/school although he/she is physically able and not precluded from work/school by virtue of his/her housing status, is not indigent for the purposes of this policy and is not eligible for free stationery or to anticipate for postage. An inmate who is selfconfined may also be considered as refusing available work although physically able as determined by the Program Review Committee (PRC). Any inmate who has funds in another account, which if deposited in his/her facility account would bring his/her balance to more than $10, is not indigent. Any inmate who has not made a good faith effort to manage his/her money so as to be able to pay the necessary costs of litigation himself/herself is not indigent.” | Stationery and a pen; up to $11 per month in copying and postage for legal mail charges; basic hygiene items. | No. | DC-ADM 803 and DC-ADM 815 |

| Rhode Island | “One who is involuntarily unemployed, has less than $10 in their active account, and has had no deposits of $10 or more in the previous two months.” | An indigent kit every thirty days which includes 1 bottle of shampoo, one tube of shaving cream, two disposable razors, one writing pad, six #10 envelopes, one soap bar, one tube of toothpaste, one tooth brush, one writing pen, three two-packs of generic pain reliever, and one deoderant stick; three personal letters per week and legal mail. | No. | 2.25-03 DOC and an email exchange with RIDOC on 10/7/2021. |

| South Carolina | “An inmate whose E.H. Cooper account’s balance and/or deposits for a 30 day period has not exceeded $6.42.” | A pair of clogs or tennis shoes (bobos) for recreational purposes if their state-issued, job-specific shoes are not authorized for wear during recreational activities; a hygiene pack that includes three soaps, one pencil, one tube of toothpaste, one toothbrush, one deodorant, two envelopes, eight sheets of paper, two 3-in-1 gels for men or three 3-in-1 gels for women, four disposable razors, and a comb. | No. | ADM-16.08 and ADM-15.13 |

| South Dakota | “Their spend funds are less than $1.00; they have no commissary purchases in the last calendar month and had no deposits in the last calendar month.” | Unknown. | Yes. Indigent people receive items from “indigent commissary” every 30 days, and any items they accept will be debited with a credit obligation | 1.2.E.1 |

| Tennessee | Indigence definition not available. | Two postage stamps per pay period; first class postage for outgoing legal mail; religious materials if someone donates them (e.g., volunteers, outside clergy, or other outside organizations). | No. | 507.02, 118.01, and 507.03 |

| Texas | “When a TDCJ offender. (1) has less than a $5 balance in an inmate trust fund (ITF) account; (2) has a damaged or misplaced identification (ID) card; or (3) is on week one of lockdown status for more than seven consecutive days.” | None. | Yes. Indigent people can receive stationery and postage but it must be paid back when funds are placed into their accounts. The same is true for medical co-pays—they don’t have to pay upfront but the charges will accumulate and the DOC will expect payment whenever funds are placed in their accounts again. | BP-03.91 and TDCJ Annual Health Care Services Fee Pamphlet |

| Utah | “An inmate who has not had over nine dollars in his or her inmate account for 45 consecutive days may be eligible for indigent status.” | Duplication of medical records; one first class, one-ounce envelope per week; personal hygiene items including a toothbrush every 3 months, toothpaste, soap, a small comb, and one disposable razor every week; duplication of legal records (up to 25 per week); writing materials including writing paper, envelopes, pencils and pens; I.D. cards (and they don’t have to pay for a replacement if it’s lost or stolen). | No. | Inmate Orientation Handbook and Inmate Health Care information page |

| Vermont | Indigence definition not available. | Socks and undergarments upon arrival; hygiene items; if someone orders something from commissary and is released before receiving the items, they may be donated to those who are indigent. | No. | Inmate Handbook |

| Virginia | “An offender with less than $5.00 in their offender account for discretionary spending during the previous month and has no job or other source of income that provided as much as $5.00 during the previous month or an offender who is newly received into a facility and does not have available funds nor hygiene items.” | Hygiene items including toothbrush, toothpaste, denture cleaner and adhesive, shampoo, deodorant, comb, razor, and bar soap; legal package including paper, pen, carbon paper, and manilla envelope; postage for one one-ounce, domestic, first class letter per week; $50 stipend each year for copies of offender notification information. | Yes. If an indigent person participates in Ramadan or NOI Month of Fasting, they have to pay for their meal tray between dawn and sunset. The cost will be charged as a loan if they don’t have a sufficient amount to cover the cost. | 050.1, 866.3, 802.2, and an email exchange with VADOC on 10/12/2021. |

| Washington | “An inmate who has less than a twenty-five dollar balance of disposable income in his or her institutional account on the day a request is made to utilize funds and during the thirty days previous to the request.” | None. | Yes. Indigent people will not be denied access to personal hygiene items, or medical, dental, or mental health care but they will have to pay the money back once they have money available. Additionally any money spent on postage for regular and legal mail will also have to be paid back. | RCW 72.09.015, DOC 440.080, WAC 137-48-060 |

| West Virginia | Indigence definition not available. | Mail letters to attorneys or the courts using a stamped envelope; an “indigent package” (no further explanation provided). | No. | Offender Orientation Manual |

| Wisconsin | Indigence definition not available. | If they are transgender or intersex, they can ask the health services unit for Magic Shave without a copay; basic hygiene items; feminine hygiene products are free; free stamped envelope biweekly and two free phone calls per week; one free haircut per month; state issued shoes, clothing, linens, and towels; over the counter medication; state issued glasses if prescribed; free state-issued ID upon return to community. | Yes. The DOC will loan up to $100 annually to indigent people for supplies, photocopies, and postage to allow them access to the courts for litigation related to their own cases. | 500.70.27, 309.51.01, and an email exchange with WI DOC on 10/13/2021. |

| Wyoming | “An inmate who has no source of income and no money on his/her account. Inmates who have twenty-five dollars ($25.00) or more credited to their account at any time in any given month from any source for discretionary spending shall not be considered indigent during that month regardless of their account balance at any time during that month.” | Use of pens and paper when in the law library; replacement glasses; Hygiene items including soap, toilet paper, and a tooth brush, toothpaste, denture cleaner and adhesives, shaving equipment and “special hygiene needs.” | Yes. Costs of mailings, printing, photocopying, and any indigent mail packets they are given will result in debt. They will accrue indebtness until they’ve reached 180 days of indigency, at which point there will not be additional charges for the subsequent period of consecutive indigence. If they receive outside money, up to 50% will be taken for reimbursement towards indigent indebtness. | 3.401, 4.322, 4.201, and an email exchange with WY DOC on 10/15/2021. |

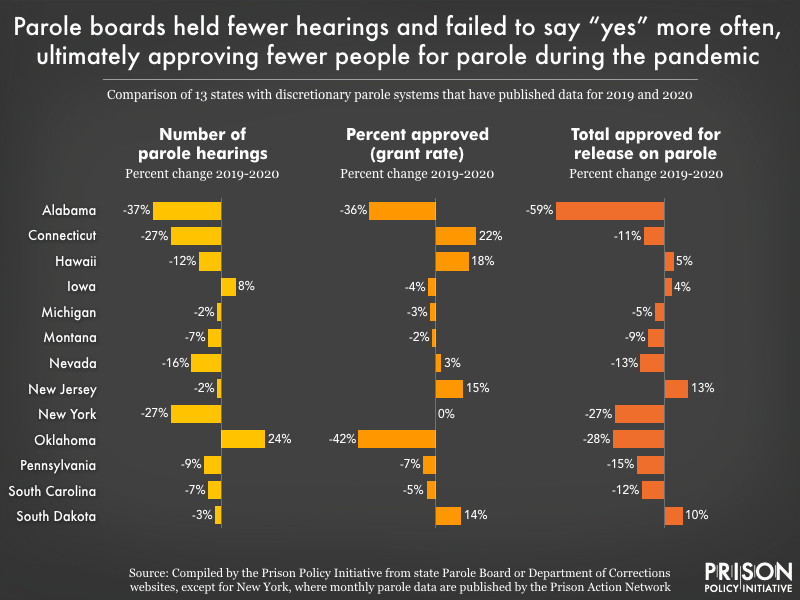

Of the 34 states with discretionary parole, we were able to find parole data for both 2019 and 2020 for these 13 states. Four states – Alabama, Hawaii, Iowa, and New Jersey – report their parole data by the fiscal year instead of the calendar year. Thus, the impact of the pandemic on parole releases may appear less extreme in these four states. (Fiscal Year 2020 data from Alabama reflects hearings held between Oct 1, 2019 and Sept 1, 2020, while Fiscal Year 2020 data in the other three states reflects hearings held between July 1, 2019 and June 30, 2020.) We’ve still included these states, however, as they capture early parole responses to the pandemic.

Of the 34 states with discretionary parole, we were able to find parole data for both 2019 and 2020 for these 13 states. Four states – Alabama, Hawaii, Iowa, and New Jersey – report their parole data by the fiscal year instead of the calendar year. Thus, the impact of the pandemic on parole releases may appear less extreme in these four states. (Fiscal Year 2020 data from Alabama reflects hearings held between Oct 1, 2019 and Sept 1, 2020, while Fiscal Year 2020 data in the other three states reflects hearings held between July 1, 2019 and June 30, 2020.) We’ve still included these states, however, as they capture early parole responses to the pandemic.