New data reveals where people in Louisiana prisons come from

Report shows every community is harmed by mass incarceration

July 13, 2023

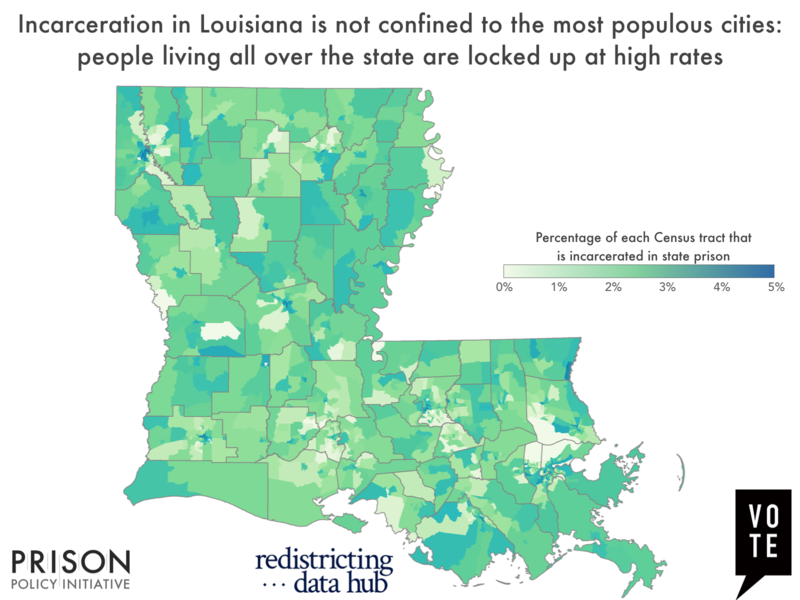

Today the Voice of the Experienced (VOTE), the Redistricting Data Hub, and the Prison Policy Initiative released a new report, Where people in prison come from: The geography of mass incarceration in Louisiana, that provides an in-depth look at where people incarcerated by the state’s Department of Public Safety & Corrections (DPS&C) come from. The report also provides nineteen detailed data tables — including neighborhood-specific data for New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Shreveport, and Jefferson Parish — that serve as a foundation for advocates, organizers, policymakers, data journalists, academics, and others to analyze how incarceration relates to other factors of community well-being.

The report shows:

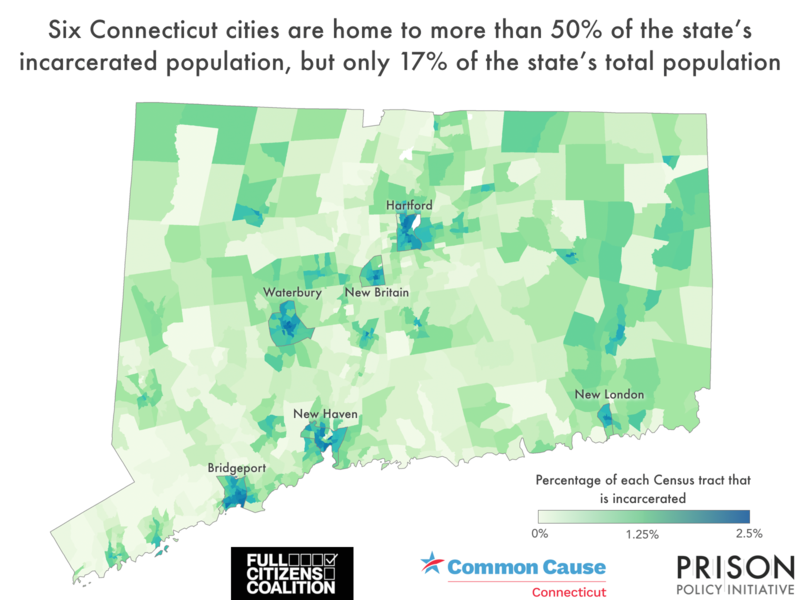

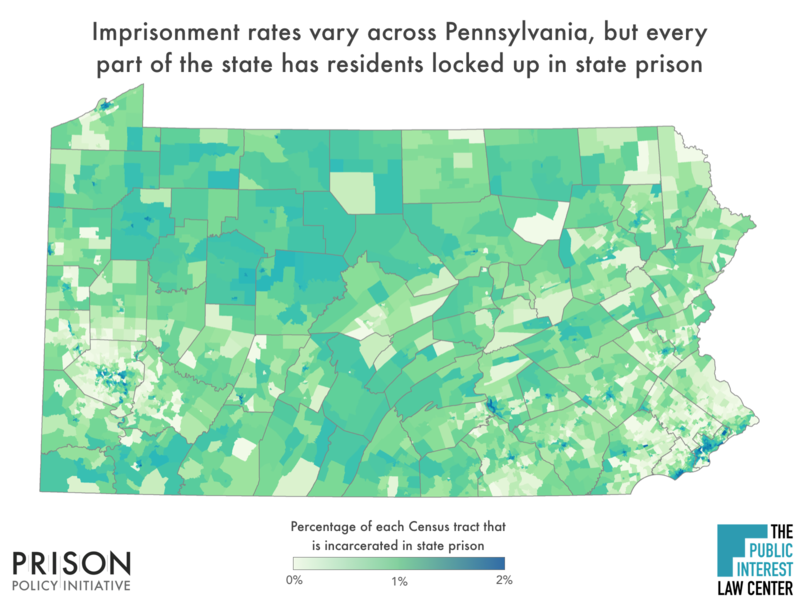

- Every single parish — and every state legislative district — is missing a portion of its population to incarceration in state prison.

- While the state’s largest cities have the most people incarcerated, many of the state’s smallest communities have the highest imprisonment rates, including Bogalusa, which has an imprisonment rate of 1,661 per 100,000 residents in the custody of DPS&C. For comparison, Louisiana has an imprisonment rate of 451 per 100,000 residents.

- There are dramatic differences in incarceration rates within communities. For example, in New Orleans, one of the most racially segregated cities in the nation, residents of B.W. Cooper are 47 times more likely to be imprisoned than residents of the neighboring Lakeview neighborhood.

Data tables included in the report provide residence information for people incarcerated by the Louisiana Department of Public Safety & Corrections in 2022, offering the clearest look ever at which communities are most impacted by mass incarceration. They break down the number of people locked up by parish, city, town, zip code, legislative district, census tract, and other areas.

The data show that the parishes with the highest state prison incarceration rates are Washington (901 per 100,000 residents), Franklin (788 per 100,000 residents), and Caddo (753 per 100,000 residents). For comparison, Ascension Parish has the lowest prison incarceration rate, at 195 people in state prison per 100,000 residents, four times lower than Washington Parish.

“The nation’s 40-year failed experiment with mass incarceration harms each and every one of us. This analysis shows that while some communities are disproportionately impacted by this failed policy, nobody escapes the damage it causes,” said Emily Widra, Senior Research Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. “Our report is just the beginning. We’re making this data available so others can further examine how geographic incarceration trends correlate with other problems communities face.”

The report cites studies that show that incarceration rates correlate with a variety of negative outcomes, including higher rates of asthma, depression, lower standardized test scores, reduced life expectancy, and more. The data included in this report gives researchers the tools they need to understand better how these correlations play out in Louisiana.

“Louisiana has led the way on the use of incarceration as the solution to complicated social struggles, and this approach has specifically targeted Black communities since the beginning,” says Bruce Reilly, Deputy Director of VOTE. “This data illustrates the scope of mass incarceration, as every town and city feels the pain. Lawmakers have consistently chosen to fund the police and prison industry rather than invest in communities, as they routinely file more bills on criminal justice than any other issue area. We hope that continued education can put a stop to this trend that has spanned over two centuries.”

The report, which is part of a series of reports examining the geography of mass incarceration in America, is available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/origin/la/2022/report.html.