States of Women’s Incarceration: The Global Context 2018

By Aleks Kajstura

June 2018

U.S. incarceration of women remains at historic and global high

Despite recent reforms, the United States still incarcerates 698 people for every 100,000 residents, more than any other country. Compared to that number, the women’s incarceration rate of 133 seems quaint. But it’s the highest incarceration rate for women in the world. And while the overall U.S. incarceration rate is falling, the women’s rate remains at an historic high.

This report updates how U.S. women fare in the world’s carceral landscape, comparing incarceration rates for women of each U.S. state with the equivalent rates for countries around the world.

Women’s incarceration across the world

Only 4% of the world’s female population lives in the U.S., but the U.S. accounts for over 30% of the world’s incarcerated women.

Figure 1. This graph shows the number of women in state prisons, local jails, and federal prisons from each U.S. state per 100,000 people in that state and the incarceration rate per 100,000 in all countries with at least a half million in total population.

Oklahoma has long had a reputation for over-incarcerating women, especially mothers dealing with drug or alcohol addictions. But having children also opens up Oklahoma women to incarceration when they are victims of abuse. In a recent illuminating case, a father violently abused a mother and her children, and got probation, but the mother was sentenced to 30 years for failing to protect their kids when he broke their daughter’s bones. As Oklahoma has become the “world’s prison capital,” the state’s women risk being further bulldozed by systems designed for men.

The rapid growth of women’s incarceration, coupled with the longstanding focus on men, means that recent criminal justice reforms have not kept up with the number and needs of incarcerated women. Women often do not have the same access to diversion and other programs that can shorten incarceration. Wyoming only recently allowed women to attend an alternative 6-month “boot camp” instead of serving 6-10 years in prison. And even then the women would have go as far as Florida to serve their time, because Wyoming’s camp is only open to men. Even Texas, which incarcerates more women than any other state, has few educational or vocational programs open to the women in its facilities.

But the scope of the problem for all of these states becomes staggering when compared with countries across the world. The U.S. and its states make up 27 of the world’s most carceral places for women. Thailand comes in 28th place, fueled in part by America’s exported “war on drugs.” Women in Kansas and Thailand are incarcerated at similar rates. More states follow until El Salvador breaks the steady stream of U.S. jurisdictions as the world’s 35th most zealous incarcerator of women. El Salvadorian women are still routinely jailed for miscarriages, and have the same incarceration rate as women in Wisconsin.

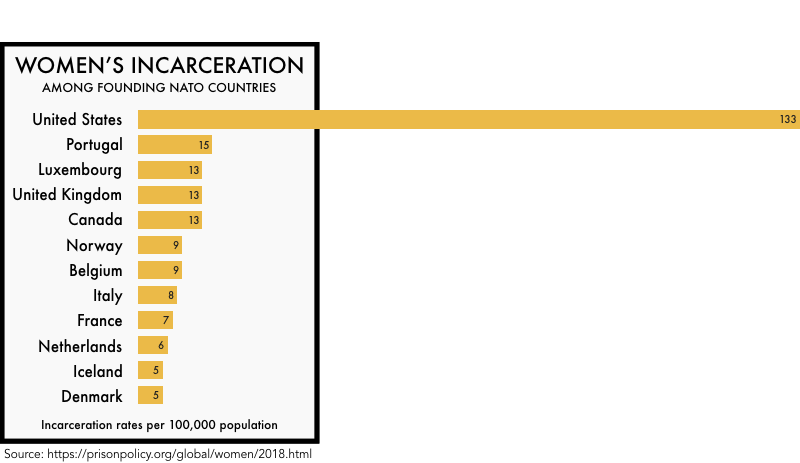

The true scale of U.S. over-incarceration becomes even more apparent when we look to our closest allies, the fellow founding countries of the North American Treaty Organization (NATO). The U.S. incarcerates women over 8 times as much as any of these NATO countries.

Compare another state:

or compare just the U.S. with its peers.

Conclusion

While women are in fact incarcerated far less than men, comparing the women’s incarceration rate to that for men paints a falsely optimistic picture. When compared to jurisdictions across the globe, even the U.S. states with the lowest levels of incarceration are far out of line with global norms.

Methodology

Like our report, Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2017, this report takes a comprehensive view of confinement in the United States that goes beyond the commonly reported statistics to offer a fuller picture of this country’s different and overlapping systems of confinement.

This broader universe of confinement includes justice-involved youth held in juvenile residential facilities, women detained by the U.S. Marshals Service (many pre-trial), women detained for immigration offenses, sex offenders indefinitely detained or committed in “civil commitment centers” after completing a sentence, and women committed to psychiatric hospitals as a result of criminal charges or convictions.

We included these confined populations in the total incarceration rate of the United States and, wherever state-level data made it possible, in state incarceration rates. This data paints a more complete picture of state criminal justice policies that impact girls and women. But while we were able to get most of the data, others are unavailable, non-existent, or older than what is available for the total population.

Data about women’s incarceration remains scarce

Many common criminal justice datasets do not include separate counts of women, which makes it harder to get the full picture. For example:

- To calculate the number of women in prisons and jails, we had to use data from 2015 because that is the newest data that allows us to ensure that women held for state prisons in local jails are not counted twice. A newer version of the relevant Bureau of Justice Statistics report is available, but no longer includes a breakdown by gender, as it did in past versions.

- The U.S. Marshals Service does not report its detained population by sex.

- The number of people under military jurisdiction has not been reported by sex since 1998.

- Separate counts of women committed to state psychiatric hospitals due to criminal charges or convictions are not available.

The missing data on women held in psychiatric commitment (for evaluation or treatment as Incompetent to Stand Trial or Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity) in each state is particularly significant. Having data on justice-involved psychiatric patients is critical when looking policies to end women’s mass incarceration in particular, because incarcerated women experience mental health problems at rates significantly higher than incarcerated men. The incarceration data we do have reveal a system that is clearly broken, but fixing it would be easier and more efficient if policy makers had complete and detailed data.

Not directly comparable with previous report

This report is not directly comparable with our 2015 report States of Women’s Incarceration: The Global Context because of several methodological improvements, including:

- We were able to develop a way to estimate the number of women in federal prisons from each state.

- We were able to include the number of women incarcerated in Indian country jails.

- We were able to include the number of girls confined in youth facilities. (Following the methodology of our Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie report, this report takes the comprehensive view and includes all youth detained or committed outside of the home for justice system involvement).

Of these improvements, the most significant is the reallocation of women incarcerated in federal facilities. As readers of the previous edition of this report may remember, West Virginia hosts federal correctional facilities, driving up the number of incarcerated women within the state. But this time we were able to get data to reallocate women incarcerated in federal prisons back to their home states — the states that sent them to prison in the first place. This change in data brings Oklahoma “back” up to the top, as expected.

As a result of our choice to include other systems of confinement in our incarceration rates, and to reallocate women in federal prisons back to the states, this report creates a unique U.S. dataset that offers a complete look at all kinds of justice-related confinement in each state. We explain our specific data sources in more detail below and provided the raw data for the component parts of our calculations in an appendix to this report.

Our data on other countries comes from the indispensable Institute for Criminal Policy Research’s World Prison Brief.

Detailed data notes and sources

For the 50 U.S. states, we calculated incarceration rates per 100,000 female population that reflect our holistic view of confinement, which include:

- women in state prison in each state,

- women in local jails in each state,

- women in federal prison from each state,

- women held in jails in Indian Country in each state,

- young women and girls held in juvenile justice facilities from each state, and

- women convicted of sex offenses involuntarily committed to “civil commitment centers” under “civil commitment” laws.

The raw data is available in a data appendix and the individual sources were as follows:

- State prisons and local jails: Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015 Appendix Table 3 reports the number of women under prison and jail jurisdiction as of December 31, 2015. This report, published in December 2016, is the newest available data that provides a combined state prison and local jail count that avoids double counting state prisoners being held in local jails by sex. (A small number of states have contractual relationships with local jails that place large numbers of state prisoners in local jails. Failing to correct for this double counting would significantly and incorrectly increase the incarceration rate for select states.)

- Federal prisons and U.S. Marshals Service: While federal prosecutions are nominally the result of federal policy, we attributed women under federal Bureau of Prisons jurisdiction to individual states, in part because federal prosecutions are of state residents and in part because federal prosecutions are often coordinated with state prosecutors and state law enforcement. (In this way, our methodology departs from the way that the Bureau of Justice Statistics calculates state rates. In Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015, federal prisoners are included in the total national incarceration rate but do not affect state incarceration rates. U.S. Marshals Service detainees are not included at all in that analysis.)

To develop estimates of the number of women in federal prison from each state, we developed a ratio of the state of legal residence for the Bureau of Prisons population as of March 26, 2016 — based on FOIA request 2016-05586 — and applied it to the total federal women’s prison population of 14,493 calculated for our report Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2017 and explained in the “Read about the data” section of that report. This calculation includes the 1,536 women under federal (largely pretrial) detention by the U.S. Marshals Service in federal detention centers and private facilities, who are often left out of similar statistics. (It does not, however, include women held in state and local facilites contracted by the U.S. Marshals Service, since a breakdown by sex was not available. Such women are counted, in this report, as part of the state prison and local jail populations where they are in custody.) While we did not have state of residence information for the U.S. Marshals population, we used the same ratio to reallocate these women to states as we did for those under BOP jurisdiction. We reasoned that women under federal jurisdiction, regardless of status (convicted, pretrial, or in transit), would likely come from the states in the same proportions. - Indian country jails: Jails in Indian Country, 2016 Appendix Table 4 reports the number of adults and youth held in jails in Indian country as of June 30, 2016 by state and by sex. Unfortunately, this survey did not include data for 5 facilities: one in Arizona, one in Nebraska, and three in South Dakota. For our calculated national incarceration rate, we used the number estimated by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (which imputes data for non-reporting facilities). For the state rates, we used the reported numbers, since estimates were not available by state.

- Youth confinement: Because the United States confines large numbers of youth through the juvenile justice system, we included these youth in our U.S. national and state incarceration rates. Young women and girls confined in places other than prison are not included in other countries’ incarceration rates in this report, but their inclusion would not change other countries’ rates much anyway. We did not make these adjustments because for most countries, these data are not available or are not comparable to the system of youth confinement in the U.S.

For youth in the U.S., the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement State Comparisons section reports the number of people younger than 21 who were detained or committed in residential placement facilities in 2015, the most recent year for which data are available, by sex and by state. We included the national total of 7,297 young women and girls in the national incarceration rate, but state of offense was not reported for 220 of these youths. Only the youth for whom state of offense was reported were included in the state incarceration rates. (For more on this population, see our more detailed report Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie.) - Civil commitment: The data on women convicted of sexual offenses who are detained or committed under civil commitment laws after their sentences are complete comes from a May 2017 email with Sex Offender Civil Commitment Programs Network President Shan Jumper, estimating that there were 6 or 7 women total, nationally (based on the SOCCPN 2016 Annual Survey). The U.S. national incarceration rate includes 7 women under this category, but they are not apportioned to any states since that breakdown was not available.

- Population data for each state, used to calculate the incarceration rates, were based on our state population estimates for December 31, 2015. Because the bulk of our incarceration counts are for yearend 2015, we averaged the U.S. Census estimates for July 1, 2015 and July 1, 2016. Our final estimate for each state is in the appendix.

One additional category of confinement is included in the women’s national incarceration rate for the United States, but not in state rates, because state-level data were not available: Immigration detention. The one-day count of women under the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in November 2017 is reported in “ICE Detention Facilities As Of November 2017” by the National Immigrant Justice Center. The analysis is based on data obtained via Freedom of Information Act request by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center; the data are available for download from the same source.

Incarcerated women in other countries: The number of women incarcerated in each country was calculated based on the Institute for Criminal Policy Research’s World Prison Brief’s Highest to Lowest - Female prisoners (percentage of prison population), which provided the percentage of each country’s incarcerated population that is female, and the corresponding list of incarcerated population totals for each country. (For some countries, the World Prison Brief includes some number of girls in the numbers of incarcerated women.) Women’s incarceration data was not available for Cuba and Uzbekistan, which were included in our overall Global Context report.

Female population in each country: For most countries’ women’s population we relied on the United Nations’ World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Total Population — Female file. For countries within the United Kingdom, the UN’s World Population Prospects and the ICPR’s World Prison Brief were incompatible, so we relied on individual country censuses for female population totals for each jurisdiction. For the United Kingdom (England & Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland) we used the United Kingdom’s Office of National Statistics’ “Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland” (File: Mid-2016, Table MYE1: Population estimates: Summary for the UK, mid-2016). Incarceration rates for the four jurisdictions within the former Yugoslavia are based on an estimated women’s population. The World Prison Brief publishes incarceration data separately for Serbia and Kosovo, and Bosnia and Herzegovina: Federation and Bosnia and Herzegovina: Republika Srpska separately, but reliable female population counts are only available for each pair of jurisdictions combined. Total population counts, however, are available for each so we estimated women’s population to be half of the total population.

Separately, to calculate the percentage of women worldwide who live in the in the U.S. we used the female population data from the World Bank.

Finally, for this report, we decided to accept the World Prison Brief’s definition of country, choosing to exclude countries only for reasons of population size. To make the comparisons more meaningful to U.S. states, we’ve chosen to include only independent nations with total populations of more than 500,000 people.

In order to make the graph comparing the founding NATO nations to individual states, however, we had to make two exceptions to this policy. First, we included Iceland, which is a founding NATO member, even though its population is below 500,000. We also aggregated the total incarcerated and total population data for the three separate nations of England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Island, into the one member of NATO, the United Kingdom.

Privacy policy

To customize this report with state data that you are most likely to find relevant, this report makes an educated but unrecorded guess about your location based on your IP address. Where we can’t make this guess, the page may request your location for that purpose. If you gave us this permission, we discarded your location data as the page finished loading. If you did not give us this permission — or if your browser was configured to decline permission automatically — this report simply gives a more generic experience.

Acknowledgements

All Prison Policy Initiative reports are collaborative endeavors, but this report builds on the successful collaborations of the 2014 and 2016 versions of the States of Incarceration: The Global Context report as well as the first edition of this report, written with co-author Russ Immarigeon in 2015. Beyond the original structure developed by data artist Josh Begley, the author of this year’s report is particularly indebted to Jordan Miner for helping with state-specific graphs, to Joshua Herman for help labeling the main graphic, to Robert Machuga and Elydah Joyce for design assistance, and to the International Centre for Prison Studies for aggregating comparable world incarceration data in the invaluable World Prison Brief. And special thanks to Peter Wagner and Wendy Sawyer for their work on the data behind this report.

This report was supported by a generous grant from the Public Welfare Foundation and by our individual donors, who give us the resources and the flexibility to quickly turn our insights into new movement resources.

About the author

Aleks Kajstura is Legal Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. Her previous publications on women’s incarceration include the first edition of States of Women’s Incarceration: The Global Context in 2015 and Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2017.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is known for its visual breakdown of mass incarceration in the U.S., as well as its data-rich analyses of how states vary in their use of punishment. The Prison Policy Initiative’s research is designed to reshape debates around mass incarceration by offering the “big picture” view of critical policy issues, such as probation and parole, women’s incarceration, and youth confinement.

Events

- April 30, 2025:

On Wednesday, April 30th, at noon Eastern, Communications Strategist Wanda Bertram will take part in a panel discussion with The Center for Just Journalism on the 100th day of the second Trump administration. They’ll discuss the impacts the administration has had on criminal legal policy and issues that have flown under the radar. Register here.

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.