Where people in prison come from:

The geography of mass incarceration in Delaware

by Emily Widra, Kyra Hoffner, and Jack Young

September 2022

Press release

In Delaware — and elsewhere throughout the country — it has always been difficult to figure out which communities incarcerated people come from. While the Census is usually useful for studying populations and informing policy decisions, it does not help identify these communities because it counts incarcerated people as residents of the district where their prison is located. But a 2010 change in Delaware state law, implemented for the first time in the current 2020 redistricting process, mandates that state officials must adjust this Census data to count incarcerated people at their last known home address.1 This adjusted data allows us to see — for the first time with a certain degree of precision — which Delaware communities are most impacted by incarceration.

Delaware is one of over a dozen states that have ended prison gerrymandering, and now count incarcerated people where they legally reside — at their home address — rather than in remote prison cells. This type of reform is crucial for ending the siphoning of political power from disproportionately Black and Latino communities. When reforms like Delaware’s are implemented, they bring along a significant side effect: To correctly represent each community’s population counts, states must collect detailed statewide data on where incarcerated people call home, which is otherwise impossible to access.

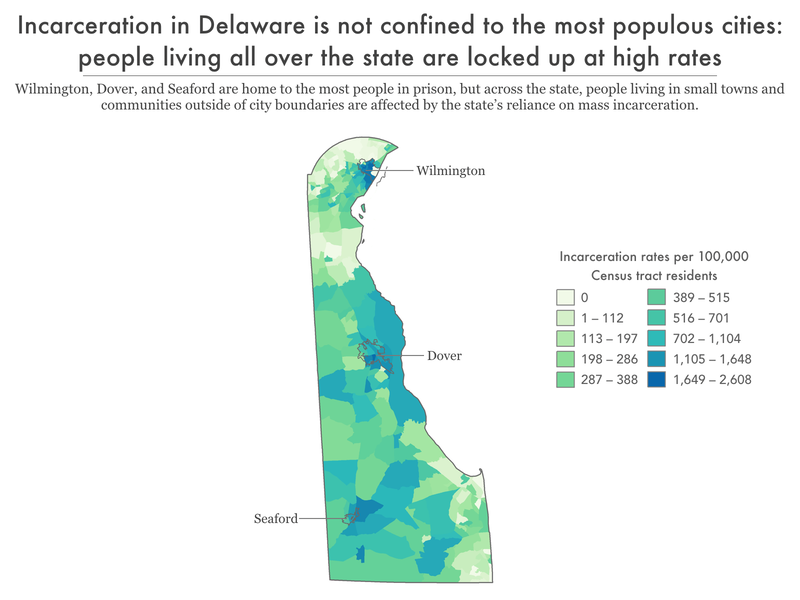

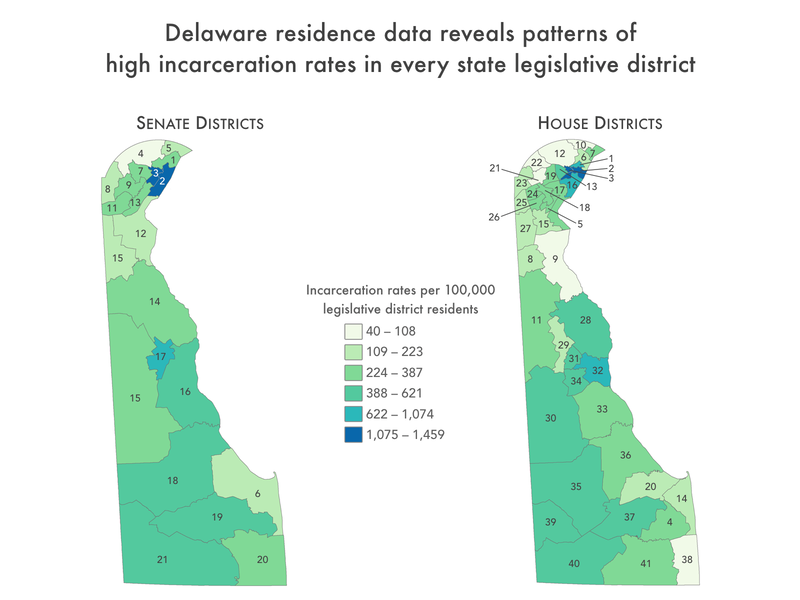

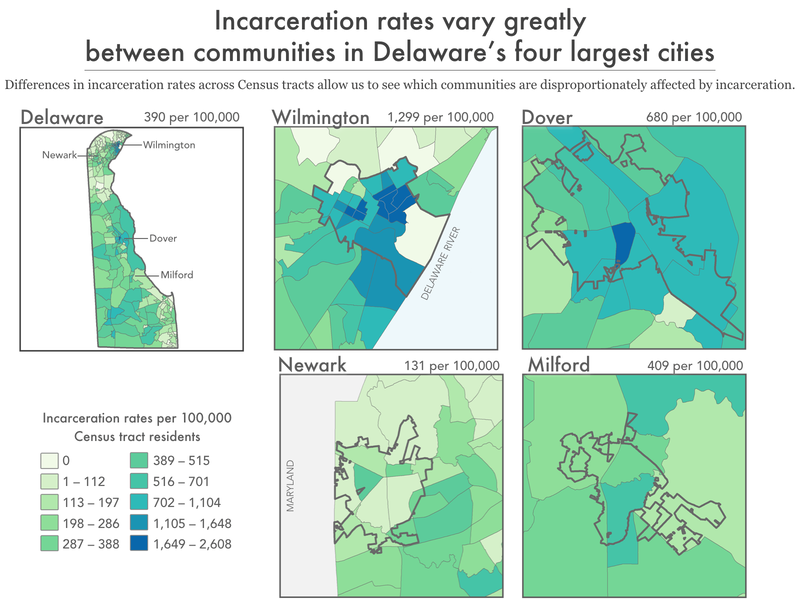

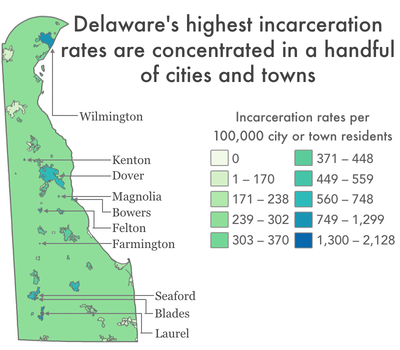

Using this redistricting data, we found that in Delaware incarcerated people come from all over the state, but are disproportionately from a few specific cities: Wilmington, Seaford, and Dover. A deeper dive into the data shows that even within these cities there are dramatic differences in rates of incarceration between neighborhoods, often along racial and socioeconomic lines.

In addition to helping policy makers and advocates effectively bring reentry and diversion resources to these communities, this data has far-reaching implications. Around the country, high incarceration rates are correlated with other community problems related to poverty, employment, education, and health. Researchers, scholars, advocates, and politicians can use the data in this report to advocate for bringing more resources to their communities.

Incarcerated people come from all over Delaware — but disproportionately from some places more than others

More than 3,700 Delaware residents are incarcerated,2 leaving the state with an incarceration rate of 380 per 100,000 Delaware residents.3 While no part of Delaware is immune to the consequences of the state’s reliance on mass incarceration, some communities are disproportionately impacted.4

City and town trends

Across all Delaware cities, Wilmington has the dubious distinction of having both the highest number of city residents incarcerated (917 people, or more than 1% of the city’s population) and the highest incarceration rate in the state: 1,299 people incarcerated per 100,000 city residents. The city with the next highest incarceration rate is Seaford, with 748 people incarcerated per 100,000 city residents, and Dover, with 680 people incarcerated per 100,000 city residents. Newark — Delaware’s third largest city — has the lowest city incarceration rate in the state, of 131 per 100,000 city residents, which is almost three times lower than the statewide incarceration rate.

Across the country, the criminal legal system disproportionately targets communities of color. This is the case in Delaware, as well. In March 2020, 62% of the incarcerated population in Delaware was Black, while the statewide population was only 24% Black. Wilmington — the city with the highest incarceration rate — also has a higher percentage of Black residents than any other Delaware city. 57% of Wilmington residents are Black, which is more than double the percentage of all Delaware residents that are Black. In Wilmington, Black people are almost four times more likely to be arrested for low level, non-violent offenses than a white person,5 and Black people account for a disproportionate 80% of the Wilmington Police Department’s arrests.

We also know that nationally, poor people are disproportionately impacted by the criminal legal system. This is true in Delaware as well: across the three cities with the highest incarceration rates — Wilmington, Seaford, and Dover — the city poverty rates are far higher than the statewide poverty rate of 11%. Wilmington and Dover have poverty rates more than double the statewide rate, and Seaford’s poverty rate is 1.5 times higher than the statewide rate.

Incarceration is not confined to just the most populous Delaware cities, however. Several small towns have surprisingly high incarceration rates. In Laurel, 48 of the 3,913 town residents are incarcerated, leaving the small town in Sussex County with an incarceration rate of 1,227 per 100,000, more than three times the statewide incarceration rate. The small, southwestern town of Blades had 11 of the 1,190 town residents locked up on Census Day 2020, resulting in an incarceration rate of 924 per 100,000, more than double the statewide average.6 For Delaware residents living outside of a city or town, incarceration rates are lower, but not insignificant: 2,016 people from outside of Delaware’s cities and towns are incarcerated at a rate of 284 per 100,000 people.

While all communities are missing some of their members to incarceration, in places where large numbers of adults — parents, workers, voters — are locked up, incarceration has a broader community impact. The substantial number of adults drained from a relatively small number of geographical areas seriously impacts the health and stability of the families and communities left behind.7

What are the differences between high- and low-incarceration communities?

Across the country, researchers have connected high local incarceration rates with a host of negative outcomes for the people who live there. In a prior analysis of where incarcerated people in Maryland are from, the Prison Policy Initiative found that Baltimore communities with high rates of incarceration were more likely to have high unemployment rates, long average commute times, low household income, a high percentage of residents with less than a high school diploma or GED, decreased life expectancy, high rates of vacant or abandoned properties, and higher rates of children with elevated blood-lead levels, compared to neighborhoods less impacted by incarceration.

Research has revealed similar correlations8 in communities around the country:

- Life expectancy: A 2021 analysis of New York State census tracts found that tracts with the highest incarceration rates had an average life expectancy more than two years shorter than tracts with the lowest incarceration rates, even when controlling for other population differences.9 And a 2019 analysis of counties across the country revealed that higher levels of incarceration are associated with both higher morbidity (poor or fair health) and mortality (shortened life expectancy).

- Community health: A nationwide study, published in 2019, found that rates of incarceration were associated with a more than 50% increase in drug-related deaths from county to county. And a 2018 study found that Black people living in Atlanta neighborhoods with high incarceration rates are more likely to have poor cardiometabolic health profiles.

An analysis of North Carolina data from 1995 to 2002 revealed that counties with increased incarceration rates had higher rates of both teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). A 2015 study of Atlanta also found that census tracts with higher rates of incarceration had higher rates of newly diagnosed STIs.10 - Mental health: A 2015 study found that people living in Detroit neighborhoods with high prison admission rates were more likely to be screened as having a current or lifetime major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.

- Exposure to environmental dangers: A 2021 study found that people who grew up in U.S. census tracts with higher levels of traffic-related air pollution and housing-derived lead risk were more likely to be incarcerated as adults, even when controlling for other factors.

In New York City, neighborhood incarceration rate is associated with asthma prevalence among adults. Similarly, in our 2020 analysis of New York City neighborhoods, we found higher rates of asthma among children in communities with high incarceration rates.11 - Education: In a 2020 analysis of incarcerated New Yorkers’ neighborhoods of origin, the Prison Policy Initiative found a strong correlation between neighborhood imprisonment rates and standardized test scores.12 And a 2017 report on incarceration in Worcester, Massachusetts, found that schools in the city’s high-incarceration neighborhoods tended to be lower-performing. In addition, students in those neighborhoods faced more disciplinary infractions.

- Community resources and engagement: A 2018 study found that throughout the country, formerly incarcerated people (as well as all people who have been arrested or convicted of a crime) are more likely than their non-justice-involved counterparts to live in a census tract with low access to healthy food retailers. And the 2017 report on Worcester, Massachusetts, revealed that high-incarceration neighborhoods had lower voter turnout in municipal elections.

There is a wealth of data showing that incarceration rates correlate with a variety of barriers and negative outcomes. The data in this report build on this work by helping identify which specific neighborhoods throughout Delaware are systematically disadvantaged and left behind. Delaware policy leaders and residents can use the data in this report to examine granular local-level and statewide correlations and choose to allocate needed resources to places hardest hit by incarceration.

Implications & uses of these data

These six data tables provided here have the potential to help advance community advocacy and future research.

First and most obviously, these data can be used to determine the best locations for community-based programs that help prevent involvement with the criminal legal system, such as offices of neighborhood safety and mental health response teams that work independently from police departments. The data can also help guide reentry services (which are typically provided by nonprofit community organizations) to areas of Delaware that need them most.

Beyond the obvious need for reentry services and other programs to prevent criminal legal system involvement, our findings also point to geographic areas that deserve greater investment in programs and services that indirectly prevent criminal legal involvement or mitigate the harm of incarceration. Decades of research show that incarceration leads to cascading collateral consequences, both for individuals and their loved ones. When large numbers of people disappear from a community, their absences are felt in countless ways. They leave behind loved ones, including children, who experience trauma, emotional distress, and financial strain. Simultaneously, the large numbers of people returning to these communities (since the vast majority of incarcerated people do return home) face a host of reentry challenges and collateral consequences of incarceration, including difficulty finding employment and a lack of housing. People impacted by the criminal legal system tend to have extremely diminished wealth accumulation. And those returning from prison and jail may carry back to their communities PTSD and other mental health issues from the trauma they’ve experienced and witnessed behind bars. Lastly, investing in core community resources to mitigate structural issues like poverty, such as housing and healthcare, will reduce vulnerabilities for criminal legal system contact.

And since we know place of origin correlates with so many other metrics of wellbeing, we can and should target these communities for support and resources beyond what we typically think of as interventions to prevent criminal legal system contact. In communities where the state or city has heavily invested in policing and incarceration (i.e., the high-incarceration neighborhoods we find in our analysis), our findings suggest that those resources would be better put toward reducing poverty and improving local health, education, and employment opportunities.

For example, we know that large numbers of children in high incarceration areas may be growing up with the trauma and lost resources that come along with having an incarcerated parent, and that these children are also more likely to experience incarceration. The information in this report can help with planning and targeting supports, resources, and programming designed to not only respond to the harms caused by incarceration but disrupt the cycle of familial incarceration.

We invite community organizers, service providers, policymakers, and researchers to use the data tables made available in this report to make further connections between mass incarceration and various outcomes, to better understand the impact of incarceration on their communities.

Methodology & data

This report capitalizes on the unique opportunity presented by Delaware’s ending of prison gerrymandering, which allows us to determine accurately for the first time where people incarcerated in Delaware come from. In this report’s linked datasets, we aggregate these data by a number of useful statewide geographies such as counties, cities and towns, and state legislative districts.

This section of the report discusses how we processed the data, some important context and limitations on that data, and some additional context about the geographies we have chosen to include in this report and appendices. The goal of this report is not to have the final word on the geographic concentration of incarceration, but to empower researchers and advocates — both inside and outside of the field of criminal justice research — to use our dataset for their own purposes. For example, if you are an expert on a particular social disadvantage and have some data organized by county, zip code, elementary school district, or other breakdown and want to add incarceration data to your dataset, we probably have exactly what you need in a prepared appendix described below.

This report and its data are one in a series of similar reports we released in 2022, focusing on 13 states — California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and Washington — which counted incarcerated people at home for redistricting purposes, and therefore also made this analysis possible. This report can also be seen as a template for other states because while not all states have ended prison gerrymandering, most state departments of corrections already have near-complete home residence records in an electronic format. States that have not yet ended prison gerrymandering should be encouraged to continue improving their data collection, and to share the data (under appropriate privacy protections) so that similar analyses could be performed.

How we processed the data

Delaware’s law ending prison gerrymandering required the Delaware Department of Correction to share the home addresses of people incarcerated on Census Day 2020 with redistricting officials, so that these officials could remove incarcerated people from the redistricting populations reported by the Census for the facilities’ locations and properly credit people to their home communities. The adjusted data was then made available for state and local officials to use to draw new legislative boundaries. As a side effect, this groundbreaking dataset allows researchers to talk in detail for the first time about where incarcerated people came from.

Creating the tables in this report required several steps which were expertly performed by Peter Horton at Redistricting Data Hub:

- Downloading Delaware’s adjusted redistricting data (shared with the Redistricting Data Hub by the Delaware State Senate), which contains the state’s entire population, with the people incarcerated in Delaware reallocated to their home addresses. As mentioned in footnote #2, Delaware is one of six states with integrated jail and prison systems and its redistricting statute does not distinguish between populations that in other states would be considered “prison” and “jail” populations. The Department of Corrections shared the necessary information for reallocation for the total incarcerated population across the eight active Department of Corrections facilities in Delaware: Baylor Women’s Correctional Institution, Hazel D. Plant Women’s Treatment Facility, Howard R. Young Correctional Institution, James T. Vaughn Correctional Center, Morris Community Corrections Center (which closed after 2020), Plummer Community Corrections Center, Sussex Community Corrections Center, and the Sussex Correctional Institution.

- Subtracting the state’s redistricting data from the original Census Bureau P.L. 94-171 redistricting data, to produce a file that represented the number of incarcerated people the state determined were from each census block statewide. (Census blocks that showed a net gain of population following the reallocation were the Census blocks that incarcerated people were reallocated to, and the amount of that change was the number of people from that block who were incarcerated on Census Day. For a different analysis that focused on both the net gains and net decreases in individual census blocks and then aggregated to counties and the final redistricting plans, see Peter Horton’s report for Redistricting Data Hub on Delaware.

- Aggregating these block-level counts of incarcerated people to each of the geography types available in the report. In cases where a census block containing an incarcerated person’s home address straddles the boundary between two geographies, the incarcerated population was applied to the geography that contained the largest portion of the census block’s area.

- Calculating imprisonment rates for each geography, by first calculating a corrected population that shows the Census 2020 population plus the number of incarcerated people from that geography; and then dividing the number of incarcerated people by the corrected total population, and then multiplied it by 100,000 to get an imprisonment rate per 100,000.

Important context and limitations on this data

Our analysis in this report documents the home addresses of 3,765 incarcerated people, which is less than the total statewide incarcerated population of 4,748. These numbers are different for a variety of reasons, including policy choices made when ending prison gerrymandering and others are just the practical outcome of valiant state efforts to improve federal census data, or the process of repurposing that dataset for this entirely different project.

From the perspective of improving democracy in Delaware, the state’s reallocation efforts were successful, reducing both the unearned enhancement of political representation in prison-hosting areas and reducing the dilution of representation in the highest-incarceration districts. From the perspective of using that data to discuss the concentration of incarceration, some readers may want to be aware of some the reasons why our report discusses the home addresses of 3,765 people when they may be aware that the Department of Corrections had slightly more people in custody on Census Day:

- Some people incarcerated in Delaware are from other states and therefore were not reallocated to homes in Delaware.

- Some addresses were unknown or could not be located for the reallocation. For example, an address on file may be incomplete or may contain only the notation “homeless” which of course cannot be applied to a specific home census block.

- Anyone whose home address by coincidence happens to be in a census block that contains a correctional facility would have been properly reallocated for purposes of ending prison gerrymandering, but their presence at that location would not, because of how we created our dataset, be apparent in this report.

Similarly, this report does not reflect the other groups of people incarcerated from communities who are not reflected in these data, because13 they were:

- Incarcerated in a federal prison, because states do not have the power to require home address data from federal agencies.

- Incarcerated in another state’s prison system. States cannot require other states to share this information, and the fact that so many states are ending prison gerrymandering is too new of a phenomenon for them to have had the chance to enter into inter-state data sharing agreements.

About the geographies

We have organized the data in this series of reports around several popular geographies, as defined by the federal government, by the state, or by individual cities, with the idea that the reader can link our data to the wealth of existing social indicator data already available from other sources.

Unfortunately, the reader may desire data for a specific geography that we have not made available — for example, their own neighborhood, as they conceive of its boundaries. Often, there was not a readily accessible and official map that we could use that defined that boundary; so where the reader has this need, we urge the reader to look for other geographies in our datasets that can be easily adapted to their needs, either one that is similar enough to their preferred geography or by aggregating several smaller geographies together to match your preferred geography.

We also want to caution subsequent users of this data that some geographies change frequently, and others change rarely, so they should note the vintage of the maps we used to produce each table. For example, county boundaries change very rarely, and when they do, it is often in extremely small ways. On the other hand, legislative districts may change frequently and significantly, so depending on your goals some specific tables may be applicable for your future use.

Finally, readers should note that occasionally the incarcerated numbers in our tables for some geographies will not sum precisely to the total 3,765 home addresses used in this report. That discrepancy arises because of how census blocks — the basic building block of legislative districts — nest or fail to nest within geographies drawn by agencies other than the Census Bureau.

Footnotes

Criminal legal system data is often poorly tracked, meaning researchers must cobble together information from different sources. But by using complete data from state redistricting committees, this report (and a series of other state reports that the Prison Policy Initiative developed with state partners) are uniquely comprehensive and up-to-date. The series includes two previous reports on Maryland (published in 2015, in collaboration with the Justice Policy Institute) and New York (published in 2020, in collaboration with VOCAL-NY), and our newest reports on California, Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington.

While these reports are the first to use redistricting data to provide detailed, local-level data on where incarcerated people come from statewide, other organizations have previously published reports that focused on individual cities or that provided data across fewer types of geographic areas. For example, the Justice Mapping Center had a project that showed residence data for people admitted to or released from state prisons each year for almost two dozen states. That project made those states’ annual admission and release data available at the zip code and census tract levels, most recently mapping 2008-2010 data.

Another resource (particularly helpful for states that are not included in our series of reports) is Vera Institute for Justice’s Incarceration Trends project, which maps prison incarceration rates for 40 states at the county level, based on county of commitment (meaning where individuals were convicted and committed to serve a sentence, which is often but not necessarily where they lived). ↩Delaware is one of six states with integrated jail and prison systems. People who have been sentenced to crimes and those held pretrial are both under the authority of the Department of Corrections. For the purposes of this report, we are referring to the total combined Department of Corrections’ incarcerated population across the eight active Department of Corrections facilities in Delaware: Baylor Women’s Correctional Institution, Hazel D. Plant Women’s Treatment Facility, Howard R. Young Correctional Institution, James T. Vaughn Correctional Center, Morris Community Corrections Center (which closed after 2020), Plummer Community Corrections Center, Sussex Community Corrections Center, and the Sussex Correctional Institution. ↩

As explained in the methodology, this report’s incarceration rate is based on the number of people incarcerated in Delaware who were reallocated to individual communities as part of the state’s law ending prison gerrymandering. This number is necessary for making apples-to-apples comparisons of incarceration between specific communities and the state. For the purposes of comparing incarceration in Delaware with that of other states, other more common metrics would be more useful. For these other uses, we would recommend using other numbers for the statewide incarceration rate, likely either the 314 per 100,000 published by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in Prisoners in 2020 for the number of people in state prison per 100,000 residents, or our more holistic number of 631 per 100,000 residents used in States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021 that includes people in state prisons, federal prisons, local jails, youth confinement, and all other forms of incarceration. ↩

In other reports in this series of reports on where people in state prison come from, we have presented incarceration rates by county. Because Delaware only has three counties, the county data is less helpful in understanding the local impact of imprisonment in Delaware. However, the number of people incarcerated from each county and the incarceration rate for each county are available in the appendix. Delaware has only one congressional district, so we did not include incarceration data by congressional district. ↩

In this analysis from the Police Scorecard Project, “low-level” offenses are typically classified as misdemeanors and include the following types of offenses: drug offenses, public drunkenness and other alcohol-related offenses; vagrancy, loitering, gambling, disorderly conduct, prostitution, vandalism, and “other minor non-violent offenses.” ↩

Both the town of Laurel and the town of Blades have historically higher rates of poverty than the statewide average. In 2014, the poverty rate in Laurel was 25%, more than double the statewide poverty rate. In 2000, 20% of residents in Blades were living in poverty. As discussed throughout the report, poor communities are disproportionately impacted by the criminal legal system and the cycle of incarceration is often exacerbated by poverty. ↩

These impacts of incarceration on families and communities include higher rates of disease and infant mortality, housing instability, and financial burdens related to having an incarcerated loved one. For more detailed information on how incarceration impacts families and communities, see On life support: Public health in the age of mass incarceration from the Vera Institute of Justice. ↩

These various correlative findings are once again in line with previous research on health disparities across communities, which have been linked to neighborhood factors such as income inequality, exposure to violence, and environmental hazards that disproportionately affect communities of color. Public health experts consider community-level factors such as these — including incarceration — “social determinants of health.” To counteract these problems, they suggest taking a broad approach, addressing the “upstream” economic and social disparities through policy reforms, as well as by increasing access to services and supports, such as improving access to clinical health care. ↩

We also know that people who have been incarcerated have a shorter life expectancy than people who have not. ↩

There are many additional studies linking incarceration rates and high community rates of STIs, including gonorrhea and chlamydia in North Carolina. ↩

Asthma prevalence has been used as a tool to measure population health in both sociological and public health research because it is easily correlated with environmental factors, like air quality and triggers (i.e., secondhand smoke, mold, dust, cockroaches, dust mites), access to appropriate healthcare, and healthcare literacy. See the American Lung Association’s Public Policy Position for a literature review of the relevant public health research. ↩

Again, this finding is consistent with previous research on the relationship between education and imprisonment rates. We previously reported that the high school educations of over half of all formerly incarcerated people were cut short. This is in line with earlier studies showing that people in prison have markedly lower educational attainment, literacy, and numeracy than the public and are more likely to have learning disabilities. We also know there are relationships between parental incarceration and educational performance. ↩

This list of groups of people who could not be counted at home is yet another set of reasons why the U.S. Census Bureau is the ideal agency to end prison gerrymandering: they are the only party with the ability to provide a complete solution and they can do this work far more efficiently than the states can. ↩

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Redistricting Data Hub, particularly Peter Horton, for providing valuable technical expertise and the key data in the appendix tables. Redistricting Data Hub’s assistance processing the redistricting data and connecting us with other demographic data enabled us to produce and distribute these reports faster and more affordably than would otherwise have been possible.

About the authors

Emily Widra is a Senior Research Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. She is the co-author of States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021. She is the organization’s expert on health and safety issues behind bars, including the coronavirus in prisons. Her previous research also includes analyses of mortality in prisons and the combined impact of HIV and incarceration on Black men and women.

Kyra Hoffner has been actively working and volunteering in Delaware in a variety of organizations for the past decade. She has spent numerous hours in Legislative Hall as a lobbyist with the League of Women Voters, fighting for civil rights, as well as holding the position of co-chair of the People Powered Fair Maps Redistricting Team. In the 2020 redistricting process, Kyra partnered with 19 other organizations to produce fair district maps for the State of Delaware. In this process, she held more than 100 workshops to educate the public on the process. Through this process, she protected several communities of interest and gave them the transparency and opportunity for public comment that they deserve. Kyra is a proud member of NAACP, Network Delaware, Sierra Club, Delaware United, Planned Parenthood, and ACLU (Smart Justice).

Jack Young is an adjunct professor of comparative election law and voting rights at the William & Mary School of Law and co-chair of the League of Women Voters of Delaware, Inc. Fair Maps Project. He is a life fellow of the American Bar Foundation, life member of the American Law Institute and a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (U.K.).

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative produces cutting-edge research that exposes the broader harm of mass criminalization and sparks advocacy campaigns that create a more just society. In 2002, the organization launched the national movement against prison gerrymandering with the publication of Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in New York. This report demonstrated how using Census Bureau counts of incarcerated people as residents of the prison location dilutes the votes of state residents who do not live next to prisons, in violation of the state constitutional definition of residence. Since then, New Jersey is one of over a dozen states that have used Prison Policy Initiative’s research to end prison gerrymandering.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.