State of Phone Justice 2022:

The problem, the progress, and what's next

by

Peter Wagner and

Wanda Bertram

December 2022

(Update on July 18, 2024: The FCC officially approved new telecommunications rules for prisons and jails, in response to the Martha Wright-Reed Act. Check out our briefing for a full summary of how these new rules will help incarcerated people and their families.)

- Table of Contents

- The progress

- On prison and jail phone rates

- On ancillary fees

- How states have brought down costs

- How companies are evolving to evade regulation

- What’s next: recommendations for Congress, the FCC, and state and local governments

- Appendices and rate data

At a time when the cost of a typical phone call is approaching zero, a few companies are charging millions of consumers — the families of people in prison — outlandish prices to stay in touch with their incarcerated loved ones. The cost of everyday communication is arguably the worst price-gouging that people behind bars and their loved ones face. We gathered data showing that while some jails have negotiated rates as low as 1 or 2 cents per minute1 — proving the possibility of much lower phone rates — the vast majority of jails charge 10 times that amount or more.

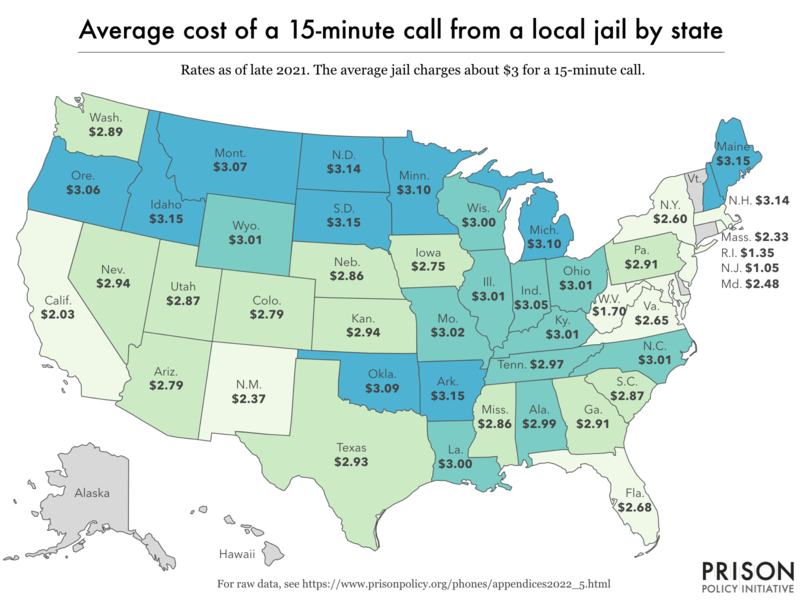

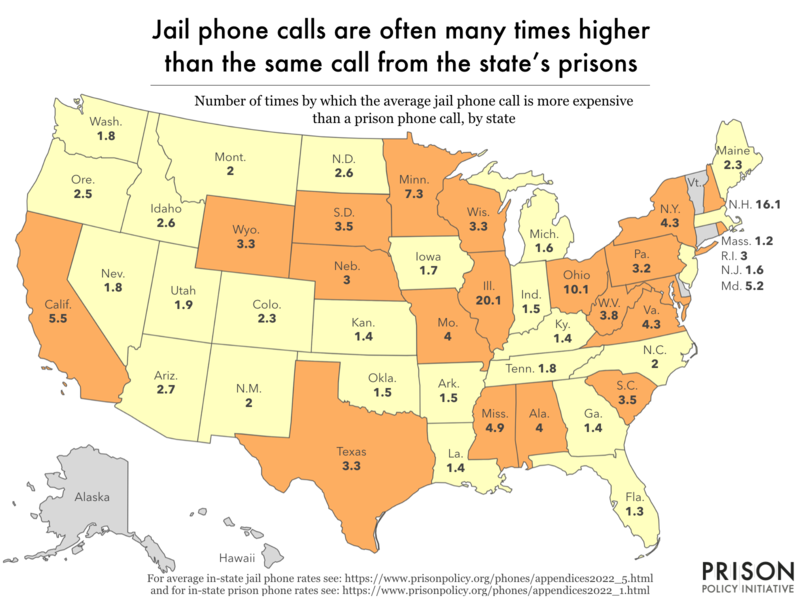

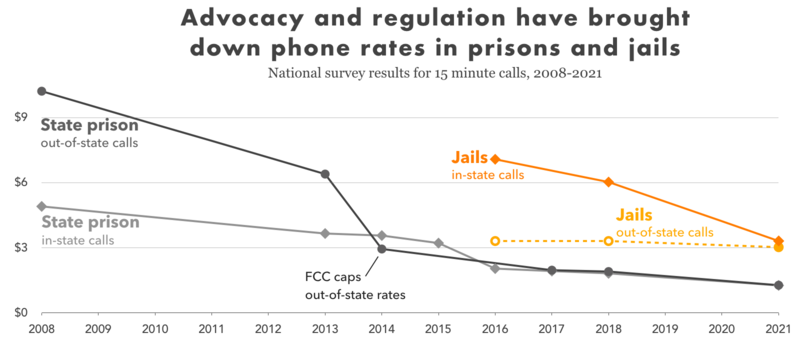

Data for these graphics comes from reports filed by the companies with the Federal Communications Commission about rates charged in 2021, and corrected and verified by the Prison Policy Initiative as described in our methodology. For our complete dataset of phone rates in jails across the U.S., see Appendix table 3. For our complete survey of phone rates in state prisons, see Appendix table 1. Data for Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, and Vermont are not shown, because these states each run a unified prison and jail system, so the role of independent county jails in other states is served by the state prison system.

Why are the (mostly low-income) people who want to maintain a relationship with incarcerated loved ones forced to use services that charge shockingly high prices for basic communications technology? Because jails and prisons often choose their telecom providers on the basis of which company will pay the facility the most money in kickbacks. Combine the companies’ profit-seeking with the correctional facilities’ revenue-seeking, and the poorest families in the country end up paying higher rates to stay connected than anyone else.

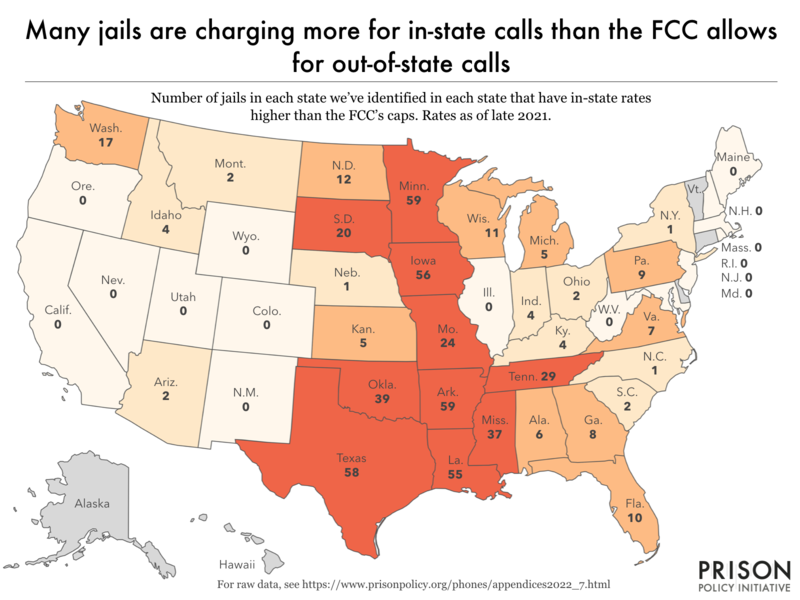

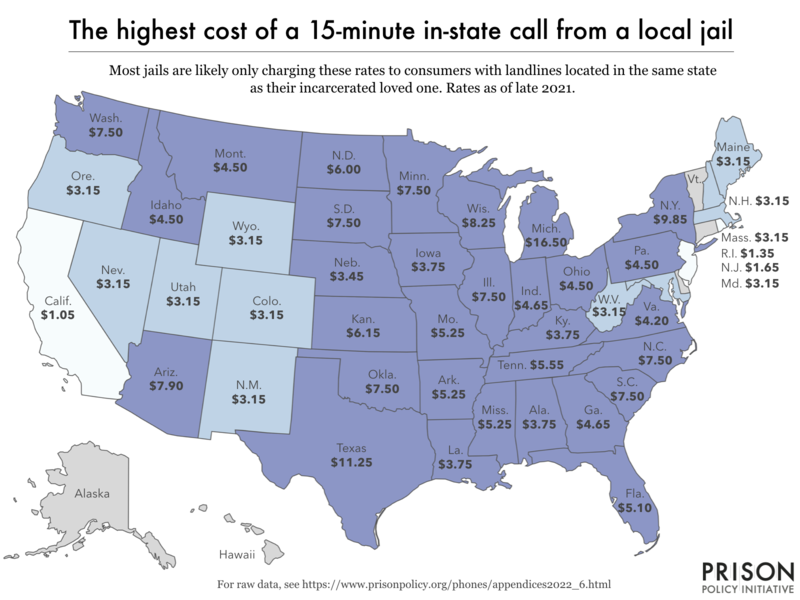

Rates for telephone calls from prisons and jails have come down in recent years, thanks to regulatory action by the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”), efforts by some forward-thinking state legislators and regulatory bodies, and strong advocacy campaigns. But costs are still generally too high (especially in jails),2 some of the smaller telecom providers are charging way too much for in-state calls to landlines,3 and the larger companies are rapidly evolving their businesses to undermine all of this progress.

In this report:

- We compile phone rates for almost every jail and prison in the country.

- We provide a national-level update on how some of the phone companies are exploiting loopholes in the FCC’s rules around abusive add-on fees.

- We sound the alarm that prison phone companies are evolving their services to evade existing regulations, specifically by creating and emphasizing other technologies like video calls and messaging, which inevitably come with hefty price tags.

- We offer specific guidance to federal and state regulators and legislators.

The progress

There has been significant progress on reducing prison and jail calling charges since advocates began mobilizing around this issue more than two decades ago, and even since our last major report in this series in 2019. This section presents an up-to-date and expanded view of the costs prison and jail families must pay, and will address both parts of the charges: per-minute rates (a set amount charged for each minute that a call lasts) and ancillary fees (additional charges to have, open, fund and close accounts).

Progress on phone rates

We built a nationwide database of phone rates in 50 state prison systems, as well as thousands of local jails and other detention facilities of various types.4 Our data, from December 2021, show that per-minute rates have been steadily falling over the last ten years, a result of action at both the FCC and at the state and local levels.

Prison and jail phone companies charge two separate (and often different) rates depending on whether a call is between people in the same state or people in different states.5 When the FCC capped the cost of out-of-state calls from prisons and jails in 2014, rates instantly fell below the less-aggressively-regulated in-state calls.6 Within a few years — largely because of pressure from family members — state prisons lowered their in-state rates as well. In locally-run jails, where family organizing is more difficult and the administrators often less aggressive negotiators, the too-high costs of in-state calls were much slower to catch up, but have made tremendous progress in the last few years.

There are two other markers of progress that stakeholders with experience in this field should note:

- Collect calls largely don’t exist anymore and where they do, under the FCC’s newest rules, those calls may not cost more than pre-paid calls.

- The FCC prohibited, for out-of-state calls, the practice of charging more for the first minute of a call; and this reform spread to in-state calls as well. In fact, we know of only four jails in the entire country that still use this pricing model for in-state calls.

Progress on fees

For a long time, ancillary fees — fees to open, have, fund, and close prepaid phone accounts — added up to almost 40% of what incarcerated people and their families spent on phone calls.10 The progress on reducing these fees has been uneven compared to progress on reducing phone rates.

The FCC recognized in its 2015 order that ancillary fees “are the chief source of consumer abuse and allow circumvention of rate caps”11 and banned most fees except for five specific types12, for which it set maximums that could not be exceeded. Then until late 2021, the FCC largely focused on the rates and did not devote much attention to the loopholes the companies were exploiting.

Besides the fact that these interim caps were set in 2015 and should be further reduced, there are four other classes of abusive fees that the FCC has recently addressed or is starting to address:

- Banning the seizure of unclaimed funds. While the FCC banned “inactivity fees” in its 2015 order, that order did not explicitly prevent the companies from just seizing unused balances. The FCC closed this loophole in paragraph 71 of the September 2022 Fourth Report and Order, requiring the companies to either refund unused balances or turn over unused funds to state unclaimed asset programs.13 The funds at stake are substantial, as evidence released in a recent consumer protection settlement with ViaPath (formerly called Global Tel*Link) shows that the company took over $121 million (link no longer available) from inactive accounts between 2011 and 2019.

We expect the Fourth Report and Order to take effect sometime in 2023. - Reining in the practice of providers colluding with Western Union and MoneyGram to inflate payment fees. When the Fourth Report and Order takes effect in 2023, this fee will be set at $5.95, which should eliminate most or all of the potential for abuse.14

- Banning the practice of “Double dipping,” i.e. charging two deposit fees for the same payment transaction. As the Prison Policy Initiative has explained to the FCC, at least six providers are charging both the $3 automated payment fee and “passing through” their card processor costs for the same transactions, which results in charging the consumer, on average, 21% more than the intended $3 cap. The FCC appears to be concerned about this practice and has invited comment on these issues in paragraph 65 of the Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.15

- Ending “single call” fee abuse. The FCC’s 2015 ancillary fee reform left a loophole by which providers could deliberately and repeatedly steer consumers to a uniquely expensive call type, the “single call,” which is intended for people who do not have accounts with the provider. This practice is particularly exploitative in the jail context, where families are typically simultaneously in crisis mode and often do not have familiarity with the providers’ less-publicized and cheaper options. In 2015, these calls could cost as much as $9.99 or $14.99 each. In 2021 the FCC tweaked the rules to limit these calls to $6.95. In the FCC’s September 2022 Fourth Report and Order, the FCC adopted part of our proposal, limiting these calls to the applicable deposit fee16 plus the actual per-minute cost of the call. The FCC did not, however, endorse our suggestion that the FCC immediately reduce the deposit fee amounts.

How states have brought down costs

The struggle for prison phone justice has shown that state governments are well positioned to bring down communications costs for incarcerated people and their families. States, unlike the FCC, are not hemmed in by constraints around their jurisdiction (see footnote 6); they also have the authority to set the rules and priorities for state and local correctional facilities, as well as for state regulators.

Some steps that state legislatures have already taken to lower costs for families include:

- In-state rate caps. States can regulate the price of calls that start and end within the state — and the FCC’s out-of-state rate caps (which apply to most phone calls, as we explain in Progress on rates) will automatically be reduced to follow lower in-state rate caps. This type of regulation can take a variety of forms, but the most common are rate caps that specify the maximum per-minute rate that companies can charge. California has been the most aggressive state in this respect, setting an interim cap of 7c per minute in 2022 that applied to both prisons and jails (and, separately, the legislature passed a law months later making phone calls from state prisons free). To be effective, state rate caps should be lower than the FCC’s caps on out-of-state calls — since state rate caps equal to or greater than the FCC’s rate caps have little impact — and under the FCC’s rules, lower caps on out-of-state calls will also automatically apply to in-state calls.

- Ancillary fee reform. Under paragraph 217 of the FCC’s 2021 order, states can also set caps on ancillary fees lower than that set by the FCC. So far, California is the only state to take such steps: Its utility agency prohibits all ancillary fees except those charged when someone deposits money into an incarcerated person’s account via a third party. Alternatively, state and local governments can simply negotiate contracts that do not include payment fees.

- Prohibiting site commissions. A handful of states have restricted prisons and jails from accepting site commission revenue (kickbacks) from telecom providers, although some states have been more effective at closing all loopholes. Unfortunately, some jurisdictions have simply prohibited facilities simply from taking cash payments — which correctional facilities can circumvent by demanding commissions in the form of equipment, fancy cruises, and other forms of kickbacks.17

- Agency-sponsored calls. Also known as “making calls free,” some jurisdictions have enacted a promising type of reform under which governments that incarcerate people also pay for necessary communications costs. Even though only a handful of states and large cities have implemented this type of system,18 there are already multiple models of agency-sponsored calling from which counties and states can choose.19

Connecticut’s system is particularly clever, because the law that created it sidesteps the risk of being undermined by revenue-hungry facilities. In order to guarantee that facilities do not use other exploitative services to generate commissions they previously received from phone calls, the Connecticut law states that corrections administrators “may supplement…voice communication service with any other communication service, including, but not limited to, video communication and electronic mail services,” but that “any such communication service shall be provided free of charge to such persons and any communication, whether initiated or received through any such service, shall be free of charge to the person initiating or receiving the communication.”

As the table below shows, states have experimented with several different types of reforms that advance phone justice:

Table 1: Notable laws and regulations reducing phone call costs at the state level

| State | Statute | Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| California | SB 1008, passed in 2022, provides state-sponsored calls in prisons. | Interim rate caps (7¢ + most fees banned, effective in prisons and jails) imposed by Public Utilities Commission and rulemaking currently underway to determine permanent caps. Additionally, agency-sponsored calling in Division of Juvenile Justice facilities. (Note that since SB 1008 made prison phone calls agency-sponsored, the rate cap part of this regulation no longer applies to prisons, but it still applies to jails.) |

| Connecticut | Conn. Gen. Stat. § 18-8100 provides state-sponsored calls (prisons only; there are no county jails in Connecticut). | |

| Illinois | Rate caps (7¢/min, prison only). (730 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/3-4-1(a-5) | |

| Iowa | Public Utilities Commission approves rates and fees on a company-by-company basis. | |

| Nevada | SB 21-387 restored Public Utilities Commission’s jurisdiction over prison and jail calling. | Public Utilities Commission rulemaking currently underway (applies to both prisons and jails). |

| New Jersey | Site commission ban, broadly defined (NJSA 30:4-8.12(b)); 11¢ statutory rate cap (prisons and jails). | |

| New Mexico | Revenue-based site commissions prohibited in prisons and jails (N.M. Stat. § 33-14-1). | Rate caps (15¢/min for in-state calls, prisons and jails). Rulemaking currently underway to consider revisions. |

| New York | State facilities required to negotiate phone call rates based on the lowest cost to the consumer, and barred from receiving any portion of the revenue. N.Y. Corr. Law § 623. | |

| Oregon | Rate caps (17-21¢ for prepaid calls, jails only). ORS § 169.683. Site commissions for jails capped at 5¢ per minute. ORS 169.681. State prison site commission capped at actual costs (ORS 421.076) | |

| South Carolina | State prison system required to forego commissions or revenue from telephones. S.C.C. § 10-1-210 |

How telecom companies are evolving to evade regulation

One development in the prison telecom industry threatens to undo much of the progress described above: The exploitation families experience at the hands of prison telecom companies is no longer only related to phone calls.

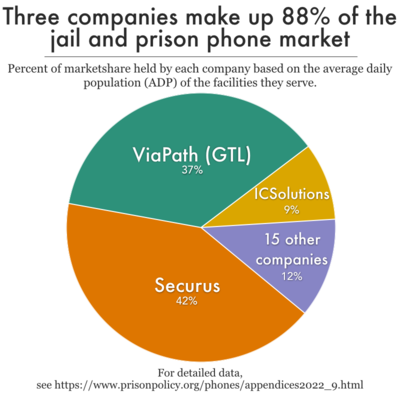

As consumer protections around phone calls have become stronger, the companies have expanded the number of costly “services” they offer to incarcerated people. ViaPath (GTL) and Securus — the two giants dominating the prison phone industry — have both expanded their offerings in recent years by buying up competitors20 that sell products like video calling, tablets, electronic messaging, release cards, and money transfer platforms that family members use to send their loved ones money for all of these products.

While these kinds of products can be a boon to families trying to stay connected, families frequently report issues such as dropped video calls and nonexistent tech support. Even when they work properly, services like video calling vary widely in price from place to place and are sold in inconvenient, inflexible time chunks — as our survey of video calling rates (below) illustrates — showing that companies are charging consumers arbitrarily high costs for services that most families use cheaply or for free.21

These non-phone products are, for the most part, less regulated than phone calls — and the companies have argued that they are outside the purview of state and federal regulators — meaning higher profits for the companies.22 Most federal and state policies seeking to lower phone call costs do not address video and other services. But there is no reason for regulators to turn a blind eye. For instance, we laid out a comprehensive legal roadmap for the FCC, explaining why the agency has the authority under current law to regulate correctional video calling. Alternatively, the Martha Wright-Reed Act, currently pending in Congress, would clarify the FCC’s jurisdiction over video calls. And if Congress fails to act, then any individual state legislature could either impose a statutory rate cap on services like video calling or explicitly grant jurisdiction over such services to the state’s utility agency. No matter who takes on these reforms, however, oversight over these companies, their contracts, and their products will be critical to ending the exploitation of incarcerated people and their families.

Table 2: Video calling rates are exploitative and arbitrary, varying widely by facility

| State | Facility | Provider | Pricing Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| MA | Barnstable County | Securus | $6.95 for 20 minutes |

| MA | Essex County | Securus | $5 for 20 minutes |

| MA | Franklin County | Securus | $5 for 20 minutes |

| MA | Massachusetts DOC | Securus | $5 for 20 minutes |

| MA | Middlesex County | Securus | $5.95 for 20 minutes |

| MA | Worcester County | Securus | $5 for 20 minutes |

| MA | Norfolk County Corr. Ctr | Securus | $7.95 for 20 minutes |

| MA | Suffolk County | Securus | $5.95 for 20 minutes |

| MT | Broadwater County | T.W. Vending | 39¢ / min |

| MT | Custer County | Securus | $12.99 for 20 minutes |

| MT | Dawson County | CenturyLink | $4 for 25 minutes |

| MT | Flathead County | Securus | $12.99 for 20 minutes |

| MT | Gallatin County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

| MT | Jefferson County | T.W. Vending | 39¢ / min |

| MT | Lewis & Clark County | T.W. Vending | 39¢ / min |

| MT | Montana DOC | ICSolutions | $4 for 25 minutes |

| MT | Park County | T.W. Vending | 39¢ / min |

| MT | Ravalli County | T.W. Vending | 39¢ / min |

| MT | Yellowstone County | Telmate | 25¢ / min |

| NJ | Camden County | ViaPath (GTL)/Renovo | $8 for 20 minutes |

| NJ | Cape May County | Securus | $10 for 20 minutes |

| NJ | Cumberland County | ViaPath (GTL)/Renovo | $6.25 for 25 minutes |

| NJ | Hudson County | ViaPath (GTL) | $4 for 10 minutes |

| NJ | New Jersey DOC | JPay/Securus | $9.95 for 30 minutes |

| NJ | Ocean County | ViaPath (GTL) | $4 for 16 minutes |

| NJ | Passaic County | ViaPath (GTL)/Renovo | $12 for 30 minutes |

| NJ | Salem County | iWebVisit | $8 for 20 minutes |

| CA | Amador County | Securus | $5.95 for 20 minutes |

| CA | Calaveras County | Securus | $9.99 for 30 minutes |

| CA | Contra Costa County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

| CA | El Dorado County | NCIC | 20¢ / min |

| CA | Fresno County | ViaPath (GTL) | 35¢ / min |

| CA | Glenn County | ViaPath (GTL) | $15 for 20 minutes (or 25¢/min if using a tablet) |

| CA | Imperial County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Inyo County | ICSolutions | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Kings County | Securus | $9 for 30 minutes |

| CA | Lake County | ICSolutions | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Lassen County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Marin County | ViaPath (GTL) | 42¢ / min |

| CA | Mariposa County | NCIC | 30¢ / min |

| CA | Monterey County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Napa County | Securus | $7.95 for 30 minutes |

| CA | Nevada County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Orange County | ViaPath (GTL) | $9 for 30 minutes |

| CA | Placer County | ICSolutions | 33¢ / min |

| CA | Plumas County | NCIC | 30¢ / min |

| CA | San Benito County | ViaPath (GTL) | $10 for 25 minutes |

| CA | San Diego County | Securus | no charge |

| CA | San Francisco | ViaPath (GTL) | city-sponsored calling — no charge to end-users |

| CA | San Luis Obispo County | NCIC | 19¢ / min |

| CA | Santa Barbara County | ViaPath (GTL) | $6 for 30 minutes |

| CA | Shasta County | ViaPath (GTL) | 40¢ / min |

| CA | Siskiyou County | Paytel | unknown |

| CA | Sonoma County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Tehama County | ICSolutions | 21¢ / min |

| CA | Tulare County | ICSolutions | 25¢ / min |

| CA | Tuolumne County | Securus | $9 for 30 minutes |

| CA | Ventura County | Securus | $6 for 30 minutes |

| CA | Solano County | iWebVisit | $9 for 30 minutes |

| CA | California Dept of Corr & Rehabilitation | ViaPath (GTL) | 20¢ / min (state pays for 15 minutes per person, every 2 weeks) |

| CA | Yolo County | ViaPath (GTL) | 35¢ / min |

| CA | Yuba County | ViaPath (GTL) | 25¢ / min |

What’s next: recommendations for further progress

While considerable progress has been made to reduce prison and jail telecom costs, prison telecom companies are still charging the families of people behind bars grossly inflated rates and inappropriate fees to communicate with their loved ones. The companies are also foisting more and more unregulated products onto the market for prison communications, and prisons and jails, eager for kickbacks, are signing contracts for bundles of these services. Families cannot help but use them.

Additionally, it is likely that there are county jails where the FCC’s recent regulation of phone call costs has not been applied. 552 county jails charge higher in-state rates than the FCC allows for out-of-state calls.23 We know that at least some of the smaller companies were unaware of the new rules about how to classify calls as in-state or out-of-state. Therefore, while some of these counties are likely charging the in-state rates as the FCC intended (i.e. only to customers with landlines located in the same state as the facility), some counties may be illegally — if unintentionally — charging a higher in-state rate for calls that the FCC has determined are out-of-state calls. Determining which of the 552 rates fall into which category requires facility-level usage data held by the companies that was not available for this report, but that can be accessed by federal or state regulators and may sometimes be available in regular commission reports sent to the facilities by their provider.24

Data for these graphics comes from reports filed by the companies with the Federal Communications Commission about rates charged in 2021 and as corrected and verified by the Prison Policy Initiative as described in our methodology and made available in Appendix table 3. The list of jails that charge more for in-state calls than the FCC allows for out-of-state calls is in Appendix table 7. Note that the FCC has two different out-of-state rate caps for jails: 21¢/minute for jails with an average daily population under 1,000; and 16¢/minute for larger facilities. A list of the most expensive in-state phone rates charged by jails in each state is in Appendix table 6.

Data for Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, and Vermont are not shown, because these states each run a unified prison and jail system, so what would be an independent county jail in other states is, in fact, state-run and therefore uses the state phone system’s contract and rates.

Families of incarcerated people deserve relief from the burden of phone call costs and an ever-growing list of unregulated technologies. Below, we offer recommendations for the government bodies with the most power to bring reform, including state legislatures, which can implement changes that dramatically reduce costs for prison and jail families as early as the next legislative session.

Policy recommendations for Congress, the FCC, and state and local governments

Congress:

- Pass the Martha Wright-Reed Just and Reasonable Communications Act, which would authorize the FCC to set “just and reasonable rates” for all calls made from correctional facilities, whether in-state or out-of-state, from jails or prisons, by phone or by video. (Note: After this report was published this measure passed Congress)

- Reform fees supporting the Universal Service Fund, thereby immediately reducing the cost of out-of-state calls by the current rate of 33%. The Universal Service Fund is an important program that raises revenue from telecommunications carriers (who pass the charge on to their customers) to support communications services for low-income people. Everyone in the U.S. who makes phone calls pays this fee in one form or another, but because incarcerated people and their families are typically poor, the federal government should exempt the industry from paying these assessments, who in turn would cease making their low-income consumers pay this fee. (The Federal Communications Commission could grant the prison and jail telephone industry a temporary forbearance immediately and make that change permanent as part of a larger effort to update the Universal Service Fund.25)

FCC:

- Regulate the cost of video calling from prisons and jails. As noted above, while phone call costs have come down due to regulatory action, most prisons and at least several hundred jails now offer video calling at rates that are arbitrary and exploitative. The FCC should, at least, take immediate steps to clarify its authority to regulate video calls.

- Take immediate action to end prison phone companies’ practice of charging multiple transaction fees for a single payment transaction (“double dipping”).

- Penalize companies that do not comply with the requirements instituted in 2015 in 47 C.F.R. S 64.6110 to “clearly accurately, and conspicuously disclose their interstate, intrastate, and international rates…to consumers on their Web sites.” As we describe in the methodology, many companies do not publish rates on their websites, and one company chooses to price its products not in dollars per minute but in dollars per megabyte.26

- Determine whether companies are getting away with charging in-state rates for calls that should be considered out-of-state, by collecting data on call volume for out-of-state and in-state calls. (To both simplify the data collection and make its purpose clear, the FCC could choose to require this data only when different rates are charged for in-state vs out-of-state calls.)

- Lower caps on per-minute phone rates further, and end the “facility size tier” rules that allow higher caps for smaller jails. (Companies and jails have argued for years that the cost of delivering services to smaller facilities is higher, thus justifying higher rate caps. But as our analysis of Michigan rates in the 2019 State of Phone Justice report shows, facility size does not actually correlate with rates.)

- Lower caps on ancillary fees. If the FCC cannot immediately set new permanent caps, the interim caps set in 2015 should be reduced based on the available data.

State governments (local governments can pass some of these reforms on a municipal scale as well):

- Enact legislation to provide agency-sponsored calls for people in prisons and jails, and such legislation should include a “technological parity” provision guaranteeing that other communications services, such as video calling and electronic messaging, are also provided for free. (Otherwise, it’s almost inevitable that prisons and jails will use other communications services to make up the lost voice calling revenue.) See our discussion of agency-sponsored calling above for more detail and links to model bills.

- While agency-sponsored calling is the most efficient solution to high communications costs in prisons and jails, states can also pass more moderate reforms:

- Direct the Public Utilities Commission to cap rates and fees for in-state calls at amounts lower than the 21¢/minute caps set by the FCC for out-of-state calls. Because of how the FCC structured its rate caps, lower caps on in-state calls will automatically also apply to out-of-state calls, thereby automatically reducing the costs for all calls.

- So that counties can benefit from economies of scale, negotiate the state prison phone contract so that small counties can opt-in to its rates and terms.

- Ensure that contracts require prison and jail telephone companies to comply with unclaimed property laws, and state treasurers should be asked to monitor compliance.27

- Ensure that contracts always specify the amounts of each fee that a company may charge. Government agencies should negotiate for lower fees so that families will have more money to spend on calls and other urgent needs. Despite the protestations of the companies, agencies will have considerable success with lowering fees when they try. For example, our November 2020 fee survey found that 15 state prison systems successfully eliminated credit card deposit fees for prepaid accounts.

Appendices

- Appendix 1:

Phone rates in state prisons, 2008-2021 - Appendix 2:

Historical jail rate data for rates-over-time graphic - Appendix 3:

Phone rates in jails/miscellaneous facilities, 2021 - Appendix 4:

Facilities still charging different first-minute rates (include first minute, subsequent minutes, and cost of a 15-minute call) - Appendix 5:

Average jail calling rates in each state (in-state and out-of-state) - Appendix 6:

The most expensive jail rates in each state - Appendix 7:

Jails charging more for in-state calls than FCC allows for out-of-state calls - Appendix 8:

Average and highest rates charged by each company - Appendix 9:

Estimates of total company market share - Appendix 10:

Companies’ inactive account policies

Methodology

This report, its visuals and its appendices pull together several different surveys of rates.

Voice-calling rates come from the following sources:

Prison phone rates (Appendix table 1):

- 2008: Prison Legal News collected the collect call rates in effect during 2007-2008. (At this time, most calls from prisons and jails were made collect.)

- 2013: Prison Legal News surveyed rates in 2012-2013. This survey is based on pre-paid rates, which was, by this time, the most common type of call from prisons and jails.

- 2014: We collected interstate (out-of-state) rates and in-state rates by two different methodologies. There is no singular survey of rates in 2014, but the PrisonPhoneJustice.org website (run by Prison Legal News) was keeping this website up to date with rate information on a rolling basis. This invaluable data collection is available historically through the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20140514050002/https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/ for May 14, 2014. Unfortunately, while PrisonPhoneJustice.org was collecting both collect and prepaid rates, only the in-state collect rates are available in this particular archive. To make the in-state collect rates comparable with the more common prepaid rates, we reduced the collect rates by 15%. (We note that in Prison Legal News’ 2012-2013 survey, prepaid rates were, with few outliers, typically 80-90% of collect rates, so we used the average difference of prepaid being 15% cheaper than collect. Additionally, we concluded that this assumption was reasonable because when the FCC set their rate caps in 2013, they set the prepaid cap of 21¢ at 15% lower than the collect rate of 25c a minute.)

For the interstate rates in 2014, we adjusted the 2013 survey data discussed above to make all states compliant with the new FCC interstate rate caps that went into effect in February 2014, limiting the cost of an interstate 15-minute call to $3.15. If states’ interstate caps were already below $3.15, we assumed their rates remained the same. Although we do not recall any instances of this, it is possible that some states may have taken the opportunity to immediately lower rates more than was required, and it is possible that our average of $2.80 is a slight overestimate. - 2015 (in-state calls only): We used the same methodology and adjustments as described above for 2014, using the Internet Archive of PrisonPhoneJustice.org for January 26, 2015: http://web.archive.org/web/20150126120301/https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/ . (Interstate rate data is not available for 2015. Once the FCC’s interstate rate caps went into effect, much of the movement’s attention turned to in-state calls and interstate data does not appear to have been preserved.)

- 2016 (in-state calls only): We used prison in-state prepaid rates data collected November 28 — December 12, 2016 by Lee Petro, at the time counsel for the Wright Petitioners and the Prison Policy Initiative and made available in a submission to the FCC. This survey did not include many of the smaller companies such as NCIC, Correct Solutions, City TeleCoin, Lattice, AmTel, etc.; and did not include Telmate’s facilities because at the time, Telmate did not publish their rates online. (Like in the previous year, out-of-state data is not available for this year.)

- 2017: For 2017 in-state and interstate rates, we used historical prepaid rate data available at prisonphonejustice.org. Each state page provides phone rates from previous years. For example, Maryland’s historical data can be found on this page: https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/state/MD/history/.

- 2018: We manually looked up prepaid rates on providers’ websites for both in-state and interstate calls in October of 2018. For in-state calls, we got a rate quote for a phone call to each state’s governor’s office, consistent with the 2016 survey methodology, and for interstate calls we used an out-of-state number.

- 2021: We obtained rates from annual reports that telecom carriers file with the FCC (Form 2301(a)) and cleaned up the data as described elsewhere in this methodology.

Jail phone rates (for rates-over-time graphic and Appendix table 3)

The rates-over-time graphic presents the average jail phone rate for 2016, 2018, and 2021. Figures from 2016 and 2018 come primarily from the rate survey we did for the first State of Phone Justice report. However, two important things to note: First, we recalculated the 2018 average rate for a 15-minute call ($5.74) to include rates charged by Reliance Telephone, which we did not have at the time of our first State of Phone Justice report. Second, the 2016 average rate excludes police lockups (temporary holding facilities inside police precincts), but subsequent years’ data do include police lockups. The 2021 averages for this graphic were calculated using data from telecom carriers’ annual reports and is described in more detail in the methodology for Appendix table 3.

Appendix table 3 represents our best attempt to report the rates for every correctional facility not classified as a “prison” under applicable FCC rules—this includes county jails, regional jails, immigrant detention facilities, secure psychiatric facilities, juvenile facilities, Indian Country jails, military correctional facilities and police lockups. These rates originate from the 2021 annual reports that telecom carriers filed with the FCC on Form 2301(a), with additional corrections and updates based on our research intended to make this table into the most comprehensive and up-to-date compendium available.28 The provider names are as listed in the annual reports, including with the name of their contracting partners, except that we standardized on referencing to GTL by their new name in the format “ViaPath (GTL).”

The FCC’s Form 2301(a) data collection is very useful in that it collects data from all providers, including those that do not publish their rates online. The data collection’s weakness is that it asks for the highest rate charged during the year, and since the FCC instituted new rate caps in October 2021, many rates decreased during 2021. Believing that it was most useful (and most expedient) to present the newest available data, we sought to update this data wherever possible.

Because it was not practical to check every rate, we focused on the rates that where one of three factors indicated that the rate was most likely to be out-of-date or incorrect:

- Where more than one company claimed to be the provider to the same facility

- Where rates were reported as being over 21¢/minute.29

- Where rates were reported as being over 16c/minute in facilities with a reported average daily population of at least 1,000 people.

When we identified rates over these caps, we performed additional verification and corrections and adjusted the vendors and rates for hundreds of counties using at least one of these methods:

- Manually checking rates on the carrier’s webpage. (Ideally, we could have used this method for all companies, but despite the requirements of 47 C.F.R. S 64.6110 to “clearly accurately, and conspicuously disclose their interstate, intrastate, and international rates…to consumers on their Web sites” not all companies publish their rates online. We were able to look up rates online during the period of April 2022 to October 2022 do this for: ATN, ViaPath (GTL) (and their subsidiary Telmate which has a different rate calculator), NCIC Inmate Communications, ICSolutions, Pay Tel, Reliance Telephone, and Securus.

- Contacting the following companies directly to verify the accuracy of their reported rates or the rates on their website: City Tele Coin, Consolidated Telecom30, Custom Teleconnect, NCIC Inmate Communications31, ViaPath (GTL), Securus, Smart Communications, Synergy Telecom, and Turnkey Corrections/TW Vending32. We also reached out to two companies — Correct Solutions and Combined Public Communications — but these companies did not respond to our written and/or phone inquiries, so we reported their rates as they appeared in these companies’ annual reports.

- Calling the jail to identify their vendor and rates. (This was our last resort and was necessary only a handful of times.)

For the purposes of the market share analysis, made available in Appendix table 9, we merged together company partnerships listed in Appendix Table 3 into the larger of the two partnering companies; and we added in the state prison contracts and populations as collected and published by Worth Rises.

Video calling rates (Table 2)

Ideally, we would have been able to present comprehensive video-calling rate data in this report, but this proved more difficult than expected because several prominent carriers (including ViaPath (GTL) and ICSolutions) refuse to publish their rate information. To present a partial view of the cost of video-calling, we collected jail video rates from four states, as follows:

- California: rates comes from carriers’ opening testimony for Phase II of the California Public Utilities Commission’s proceeding R.20-10-002.

- Massachusetts: Rates were collected by Karina Wilkinson of Prisoner Legal Services of Massachusetts.

- Montana: rates were compiled by staff of the Montana legislature’s Law and Justice Interim Committee and are available at https://bit.ly/3OVKJwZ

- New Jersey: rates were collected by Karina Wilkinson of Prisoner Legal Services of Massachusetts.

Footnotes

Dallas County, Texas charges 1¢ per minute for phone calls, while Travis County (Austin), Texas and San Mateo County, California charge 2¢ per minute. Several other correctional facilities with populations of varying sizes charge similarly low rates. These counties’ providers profit from each of these phone contracts, suggesting that the cost of delivering phone services to jails is vastly smaller than the average jail phone call rate of 21¢ per minute. ↩

Data we collected for this report (dated to December 2021) showed that in 20 states, the typical phone call home from a jail is at least three times as expensive as the same call from a state prison. (See slideshow above.) ↩

In 34 states, at least one jail charges in-state rates higher than 21¢ per minute (the maximum allowable rate under the FCC’s caps on out-of-state jail calls). As we explain later in this report, these higher in-state calling rates are mostly charged to people with landlines in the same state as the facility where their loved one is incarcerated. See our map of the number of jails per state that we’ve identified as charging more for in-state calls than the FCC allows for out-of-state calls; and Appendix table 3 for the detailed findings. ↩

Our complete database is comprised of the appendices to this report, particularly Appendix table 1 with rates for state prison systems and Appendix table 3 with rates for local jails and other miscellaneous facilities. Our survey of prison phone rates does not include rates for Federal Bureau of Prisons facilities. To our knowledge, the BOP has not posted its 2021 phone rates anywhere publicly. ↩

Phone companies serving non-incarcerated consumers also historically charged different rates for in-state and out-of-state calls. Historically, in the general phone market, rates were higher for calls between states because more distance meant higher costs. As new technology made that distinction less relevant, rates for out-of-state calls came down, and companies competed for customers by offering ever-lower prices. In the broken market for prison and jail telephone calls — where facilities pick their vendor based on who will kick back the most revenue — technological change worked out slower and differently. ↩

The FCC has successfully imposed caps on rates for out-of-state calls from prisons and jails, but not in-state calls. After the agency created regulations in 2015 that lowered the cost of both in-state and out-of-state calls, telecom providers sued the regulator, and a federal court ultimately ruled that the FCC exceeded its legal authority in capping in-state calls. Since then, the FCC has made no attempt to cap in-state phone rates, though it did succeed in changing the definition of in-state and out-of-state. A bill that recently passed in Congress, the Martha Wright-Reed Just and Reasonable Communications Act (Note: After this report was published this measure passed Congress) , would clarify the FCC’s jurisdiction to regulate the cost of phone calls from prisons and jails, both in-state and out-of-state. For now, the government bodies best positioned to regulate in-state calling rates are state governments, as we explain further in this report. ↩

For a list of the average (and highest) jail phone rates charged by each company, see Appendix table 8. ↩

For these calculations, we ignored Encartele because — for reasons and with a legality we don’t understand — that company does not price its calls in dollars per minute. ↩

As we discuss in the recommendations, whether counties are charging their in-state rates just to landlines is a factual question for investigation by advocates, the media, jail officials and federal and state regulators. Once that factual question is resolved, the question of whether such high charges to old-fashioned landlines are morally conscionable should be addressed. ↩

Because these hidden fees typically do not pay commissions, shifting the families’ costs to fees was a way for the providers to pay facilities far less than the facilities expected. For a powerful illustration of why fees are important to consider alongside rates, see the 2016 memorandum and contract between Securus and Genesee County, Michigan where the company and the jail agreed to “move fees into rates” and increase the cost of calls by 23.41c/minute so that the county and the provider could continue to make just as much money as before the FCC capped fees. ↩

See the FCC citing CenturyLink in paragraph 86 of the 2014 Second Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. ↩

The 2015 order restricted the allowed fees to: automated payment fees for electronic payments, payment fees when payments are made via a live agent, paper bill fees, single call fees, and money transfer fees. ↩

For a summary of each provider’s current policies on inactive accounts, see Appendix Table 10. ↩

Unfortunately, the FCC did not endorse our suggestion for a “more sweeping reform at this time” — which they summarize in footnote 256 to the 2022 Fourth Report and Order — to permanently end the practice of phone companies colluding with the money transfer companies to embed kickbacks within artificially inflated fees charged by those companies. Requiring the companies to declare under penalty of perjury that they are not receiving a revenue share from the money transfer companies and to back that assertion by submitting copies of their money transfer contracts to the FCC would permanently end this practice. However, by lowering the maximum allowed charge to $5.95, the FCC did, at least for the time-being and the current state of pricing at the money transfer companies, eliminate much if not all of the room in the fee to demand a kickback. ↩

For additional footnotes and context for the FCC’s notice, see paragraph 142 at https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-22-9A1.pdf. ↩

This would be $3 for automated payments and, far less common, $5.95 for a payment via a live agent. ↩

For a particularly effective framing of the reform, look to New Jersey, which chose to define “commissions” broadly as “any form of monetary payment, in-kind payment requirement, gift, exchange of services or goods, fee, or technology allowance.” ↩

As of this report’s writing, California and Connecticut are the only two states to have passed agency-sponsored calling reforms (i.e. free calls). (Massachusetts came close in 2022, but the bill was vetoed by Gov. Charlie Baker). At the local level, New York City and San Francisco have both enacted strong agency-sponsored calling programs. Similar proposals are being debated in numerous states and counties.

Not all agency-sponsored calling programs are worth celebrating, however. Some jails (such as Clay, Dakota, Ramsey, and Rice Counties in Minnesota) have provided agency-sponsored calling, but only because they eliminated in-person visitation (other than visits by attorneys). Given the paramount importance of in-person visits for maintaining family connections, this type of trade-off is not worth making. ↩

Two different models of agency-sponsored calling have evolved among the few jurisdictions that have implemented this reform. Under the first model, used in New York City, the correctional agency pays 3¢ per minute for calls, not to exceed a total of $3 million in any given year. Under the other approach, used in San Francisco, the agency doesn’t pay based on call volume, but instead pays a fixed amount per phone that’s installed in the facility. (In San Francisco’s case, the agency pays $89.78 per phone, not to exceed $1.59 million for the three-year initial term of the contract. The agency agrees to pay additional amounts for video-calling equipment.) ↩

In 2015, the year after the FCC’s first rate caps went into effect, the Huffington Post — citing leaked slides from a Securus presentation to investors — reported that Securus was purchasing JPay because its non-phone products offered “faster-growing revenue streams” than phone calls.

Appendix table 9 shows the current “market share” of each phone provider, in terms of the percent of incarcerated people covered by each provider. ViaPath Technologies (formerly called Global Tel*Link) has a 36.9% market share (i.e. provides phone service to facilities holding approximately 36.9% of all incarcerated people), while Securus has 42% market share. The market dominance of these two companies is the result of their years of buying up competitors. ↩

In fact, it gets even worse: Many prisons and jails use the new technology as an excuse to shut down critical in-person/physical services such as family visits, libraries, book donations, and mail. Shutting down these services hurts incarcerated people and may even have a negative effect on facility safety and recidivism rates (which are tied to people’s levels of contact with family during incarceration). ↩

For example, commission data from Albany County New York shows that while Securus kicks back a whopping 86% of phone call revenue back to the county, it gives the county just 20% of revenue from video visitation and eMessaging, and 10% of revenue from music, movies, and games. In November and December 2020, non-phone products amounted to more than three-quarters of Securus’ post-commissions revenue in Albany. For more on how these products give more power to the companies, see our sidebar on bundled contracts, and Stephen Raher’s law review article The Company Store and the Literally Captive Market. ↩

The FCC has two relevant caps on the cost of out-of-state calls from jails: Jails with an average daily population at least 1,000 people can charge no more than 16¢/minute, and all other jails can charge no more than 21¢ a minute. ↩

Individual jails and advocates may be able to use the jail’s commission reports to determine whether the call volume for in-state calls is suspiciously high. While, to our knowledge, there is no national figure on the number of minutes used for in-state landlines versus all other calls, we would be very suspicious of how a provider was rating calls if they reported more than 15% of their call volume was being charged the in-state rate. ↩

Also see our earlier support for a petition to the FCC asking for this relief: //static.prisonpolicy.org/phones/filings/2019-08-30PrisonPolicyInitiativeCommentOn19-232_re_USF.pdf ↩

While some companies make their rates easier to find than others, we were unable to find rates published on the websites of City Tele Coin, Combined Public Communications, Consolidated Telecom, Correct Solutions, Custom Teleconnect, Encartele, Prodigy, Smart Communications, Synergy, Talton, Turnkey Corrections. (And Encartele prices their calls in dollars per megabyte rather than dollars per minute.) ↩

State treasurers should expect all companies operating in their state in compliance with the law will be turning over unclaimed customer funds to the state unclaimed asset program in rough proportion to the number of incarcerated people served by that company. While there may be some differences in customer patterns between prisons and jails, companies turning over less funds than expected are likely to reflect either particularly aggressive and effective efforts to return customers’ money (which should be commended) or a reason to punish a company with monetary sanctions for subverting state unclaimed asset laws. ↩

For more up-to-date data on the rates published by Securus, ViaPath (GTL), and ICS, see the regularly updated data collected by our friends at Worth Rises at https://connectfamiliesnow.com/data. ↩

The FCC’s current 16¢ and 21¢ rate caps took effect in October 2021, so in many cases the companies, which had reported to the FCC the highest rates they charged during the year, had already lowered their rates during 2021 to comply with the new caps. ↩

Notably, Consolidated Telecom’s rates were accurate at the time of the FCC’s data collection, but the company informs us that it is in the process of reducing any rates over 21¢ to 20c or less, a process that the company expects to complete by the end of 2022. ↩

Notably, we corrected the average daily population for several NCIC facilities that were incorrectly reported as having an ADP of greater than 1,000 people. ↩

Notably, Turnkey Corrections/TW Vending notified us on September 16, 2022 that any rates that had been reported as higher than 21¢ were now 21¢ ↩

How to link to specific images and sections in this report

To help readers link to specific sections of this report, we created these special urls:

- Progress on phone rates

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#ratesprogress

- Progress on fees

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#feesprogress

- How states have brought down costs

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#statesprogress

- How companies are evolving to evade regulation

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#evolving

- What's next: recommendations for further progress

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#recommendations

- Recommendations for Congress

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#congressrecs

- Recommendations for the FCC

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#fccrecs

- Recommendations for state and local governments

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#staterecs

- Appendices

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#appendices

- Methodology

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#methodology

To help readers link to specific images in this report, we created these special urls:

- Average cost of a 15-minute call from a local jail by state

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#slideshows/slideshow1/1

- Jail phone calls are often many times higher than the same call from the state's prisons

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#slideshows/slideshow1/2

- Advocacy and regulation have brought down phone rates in prisons and jails

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#overtime

- Three companies make up 88% of the jail and prison phone market

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#piechart

- Many jails are charging more for in-state calls than the FCC allows for out-of-state calls

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#slideshows/slideshow2/1

- The highest cost of a 15-minute in-state call from a local jail

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html#slideshows/slideshow2/2

Learn how to link to specific images and sections

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. It launched the national fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (a.k.a. prison gerrymandering). The organization is known for its visual breakdown of mass incarceration in the U.S. and its campaigns against prison gerrymandering and the predatory prison and jail telephone industry.

Acknowledgements

All Prison Policy Initiative reports are collaborative endeavors, and this report is no different, building on an entire movement’s worth of research and strategy. The authors want to particularly thank the current and past staff members and consultants of our organization whose work this report is based on, as well as the advocates who have driven the remarkable progress to reduce prison and jail phone rates over the last decade. Lastly, we thank our donors, who give us the resources and the flexibility to quickly turn our insights into new movement resources.

About the authors

Peter Wagner is an attorney and the Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. He co-founded the Prison Policy Initiative in 2001 to spark a national discussion about mass incarceration. He is a co-author of two of the organization’s landmark reports on the dysfunction in the prison and jail phone market — Please Deposit All of Your Money in 2013 and the first State of Phone Justice report in 2019 — and has testified before the FCC in support of stronger market regulations.

Wanda Bertram is the Communications Strategist at the Prison Policy Initiative. In addition to serving as the primary media spokesperson for the organization, she has provided valuable research and insights on topics such as how the fall of Roe v. Wade will impact women on probation or parole, the exploitation of formerly incarcerated people in the labor market, and the hidden ways “prison tablets” are siphoning funds from incarcerated people and their families.

Events

- April 30, 2025:

On Wednesday, April 30th, at noon Eastern, Communications Strategist Wanda Bertram will take part in a panel discussion with The Center for Just Journalism on the 100th day of the second Trump administration. They’ll discuss the impacts the administration has had on criminal legal policy and issues that have flown under the radar. Register here.

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.