Reforms without Results:

Why states should stop excluding violent offenses from criminal justice reforms

By Alexi Jones

April 2020

Press release

- Table of Contents

- Findings

- The numbers show we cannot exclude violent offenses from justice reforms

- Why lengthy sentences don’t make sense

- 1. Long sentences do not deter violent crime

- 2. Victims want prevention, not incarceration

- 3. People convicted of violence have lower recidivism rates

- 4. People who commit violent acts are often themselves victims

- 5. People age out of violence

- 6. Many risk factors are related to social and community conditions

- There are better ways to respond to violence than incarceration

- There are alternatives to incarceration

- Communities should invest in violence prevention

- Recommendations

States are increasingly recognizing that our criminal justice system is overly punitive, and that we are incarcerating too many people for too long. Every day, 2.3 million incarcerated people are subject to inhumane conditions, offered only limited opportunities for transformation, and are then saddled with lifelong collateral consequences. Yet as states enact reforms that incrementally improve their criminal justice systems, they are categorically excluding the single largest group of incarcerated people: the nearly 1 million people locked up for violent offenses.

The staggering number of people incarcerated for violent offenses is not due to high rates of violent crime,1 but rather the lengthy sentences doled out to people convicted of violent crimes. These lengthy sentences, relics of the “tough on crime” era, have not only fueled mass incarceration; they’ve proven an ineffective and inhumane response to violence in our communities and run counter to the demands of violent crime victims for investments in prevention rather than incarceration.

Moreover, cutting incarceration rates to anything near pre-1970s levels or international norms will be impossible without changing how we respond to violence because of the sheer number of people — over 40% of prison and jail populations combined — locked up for violent offenses. States that are serious about reforming their criminal justice systems can no longer afford to ignore people serving time for violent offenses.

There are, unquestionably, some people in prison who have committed heinous crimes and who could pose a serious threat to public safety if released. And by advocating for reducing the number of people incarcerated for violent offenses, we are not suggesting that violence should be taken any less seriously. On the contrary, we suggest that states invest more heavily in violence prevention strategies that will make a more significant and long-term impact on reducing violence, which, again, reflects what most victims of violent crime want. The current response to violence in the United States is largely reactive, and relies almost entirely on incarceration, which has inflicted enormous harms on individuals, families, and communities without yielding significant increases in public safety.

Findings

Categorically excluding people convicted of violent offenses from criminal justice reforms only limits the impact of those reforms, yet almost all state reforms have focused only on those convicted of nonserious, nonviolent, and nonsexual offenses — the so-called “non, non, nons.”2 In fact, almost all of the major criminal justice reforms passed in the last two decades explicitly exclude people accused and convicted of violent offenses:

Criminal justice reforms that exclude most people in prisons:

A preliminary 50 state survey

We found states that single out violent offenses:

Block access to alternatives to incarceration |

Withhold relief from collateral consequences |

Restrict opportunities for release |

Impose two or more of these restrictions |

No examples found |

States engaging in criminal justice reform have passed at least 75 pieces of legislation that exclude the single largest part of their prison and jail populations — people convicted of violent offenses. There are also two prominent national examples not included in this map: The First Step Act and Obama’s Clemency Initiative. Note that this map is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to illustrate how widespread this counterproductive practice is. See the Appendix for a list of all examples shown here. Note that some states have passed fewer criminal justice reforms than others, so having few or no examples of “reforms” that included exceptions for people accused or convicted of violent offenses is not necessarily a positive sign.

Criminal justice reforms that exclude people convicted or accused of violent offenses3 have a limited impact, since they only apply to a narrow subset of the prison population. For example, in 2011 Louisiana passed H 138, a geriatric parole bill allowing parole consideration for people who have been incarcerated for at least ten years and are at least 60 years old. However, it excludes people convicted of violent or sex offenses,4 which account for two-thirds of the people who meet the age and time served requirements. Ultimately, only 2,600 people became eligible for parole under this new law, while 5,700 people remained ineligible because of past convictions.5 (The reader should note just how short-sighted this exclusion was, because the bill only allowed parole consideration and did not mandate actual release. Had people convicted of violence been included, the parole board could still deny release for people who posed a credible public safety risk.)

These exclusions show that legislators may be too eager to compromise in the pursuit for criminal justice reform, at the expense of most people in prison. Not all criminal justice reforms do this, however; there are examples of successful criminal justice reform efforts that include people convicted of violent offenses. For instance, Mississippi passed HB 585 (2014), which among other reforms made people convicted of various violent offenses eligible for parole after serving a smaller portion of their sentences. Mississippi’s example proves that criminal justice reforms can pass without carving out violent offenses, even in the most conservative states.67

We identified 75 criminal justice reforms in 40 states and at the federal level that exclude people convicted of violent offenses from reforms, and our search was far from exhaustive. This report does not attempt to explain the various reasons why lawmakers exclude people charged with violent offenses; our aim with this preliminary survey is simply to draw attention to these carve-outs and to enumerate the many reasons to end them. These categorical exclusions undermine states’ efforts to reduce prison populations and indicate willful disregard for the current research on violence. Instead of doling out excessive sentences in response to violent crime, states should take a proactive approach and invest in violence prevention, which is, after all, what the majority of victims of violence want.

The numbers show we cannot exclude violent offenses from justice reforms

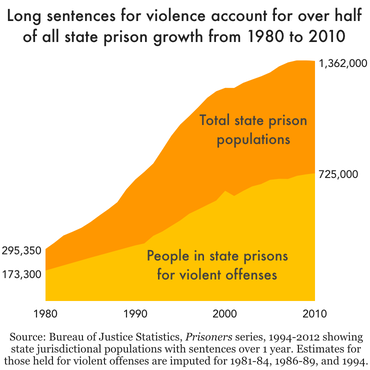

This report and this chart focus on state-level changes to policy and prison populations. Of course, “tough on crime” responses to violence also contributed to tremendous growth in the federal prison and local jail populations.

The number of people in state prisons for violent offenses increased by over 300% between 1980 and 2009, when it reached its peak of 740,000 people nationwide. This staggering increase cannot simply be attributed a higher crime rate but to a series of policy changes that states made during the “tough on crime” era of the late-1980s to mid-1990s. These policies include mandatory minimum sentences, “three strikes” laws, truth-in-sentencing laws, the transfer of young people to adult court, sentences to life without possibility of parole, and the end of discretionary parole in many places. These severe sentencing policies dramatically increased the average sentence length and restricted opportunities for release for people convicted of violent offenses, which in turn led to the massive buildup of prison populations around the country.

Specifically, between 1981 and 2016, the average time served for murder in state prisons tripled, and the average time served for sexual assault and robbery nearly doubled. These changes were coupled with a sharp increase in life sentences, nearly all for violent offenses. Since the 1980s, the number of people with life sentences increased five-fold, from 34,000 in 1984 to 162,000 in 2016.8 These extreme sentences place the United States well outside of international norms: 30% of people with life sentences worldwide are in the United States.9

Six reasons lengthy sentences don’t make sense: what the research says

These “tough on crime” policies reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of violence. They are grounded in the belief that lengthy incarceration is an effective deterrent or containment strategy for violence, despite years of evidence to the contrary, and a desire for retribution. In particular, arguments that extreme sentences are needed to protect the public assume that violence is a static characteristic in people, and that they are incapable of change. But research consistently shows people convicted of violent offenses are not inherently violent. Rather, violence is a complex phenomenon that is influenced by a range of factors, some of which diminish with time (such as youth), and others that can be mediated with interventions other than incarceration. And even when crimes warrant severe punishment, a balance must be struck between the desire for vengeance, the appropriate use of public resources, and the rights of the convicted person.

1. Long sentences do not deter violent crime

People mistakenly believe that long sentences for violent offenses will have a deterrent effect. But research has consistently found that harsher sentences do not serve as effective “examples,” preventing new people from committing violent crimes, and also fail to prevent convicted people from re-offending.10 According to a 2016 briefing by the National Institute of Justice summarizing the current research on deterrence, prison sentences (especially long sentences) do little to deter future crime. Another study concluded: “compared to non-custodial sanctions, incarceration has a null or mildly criminogenic impact on future criminal involvement.” In other words, incarceration can be counterproductive: While a prison sentence can incapacitate people in the short term, it actually increases the risk that someone will commit a crime after their release.

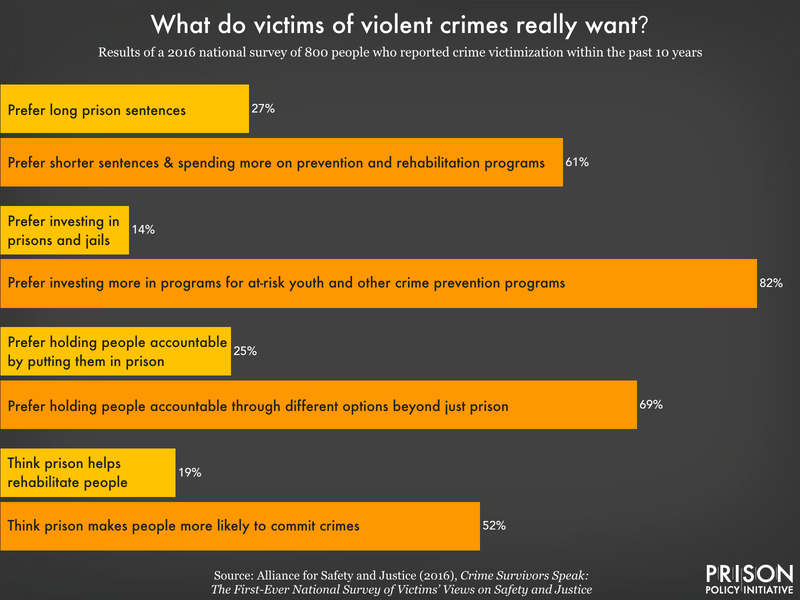

2. Victims of violence want prevention, not incarceration

Long sentences for violent offenses are also retributive, often justified in the name of victims. Yet, contrary to the popular narrative, most victims of violence want violence prevention, not incarceration. According to a 2016 national survey of survivors of violence by the Alliance on Safety and Justice:

States concerned about victims’ rights should respect these preferences, and invest in alternatives to incarceration and violence prevention.

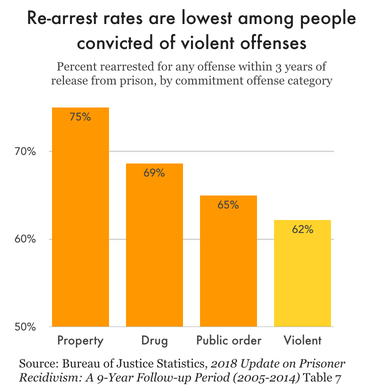

3. People convicted of violent offenses have among the lowest recidivism rates

People convicted of violent offenses have among the lowest rates of recidivism, illustrating again that people who have committed a violent act are not inherently violent and can succeed in the community.11 An act of violence represents a single moment in someone’s life, and shouldn’t be the only factor that determines their freedom.

A growing body of research finds that people convicted of violent offenses do not “specialize” in violence, and are not inherently dangerous people. The Bureau of Justice Statistics recently released two studies on 400,000 people released in 30 states in 2005. It found that while re-arrest rates are high for all people released from prison, people convicted of violent offenses are less likely to be re-arrested within 3 years12 for any offense than those convicted for nonviolent offenses. Moreover, they were only marginally more likely to be re-arrested for a violent offense than people convicted of public order and property offenses. Finally, only 2.7% of the estimated 7,500 people who had served time for homicide were re-arrested for a homicide; they were much more likely to be subsequently re-arrested for nonviolent property offenses (24.4%), drug offenses (26.1%), or public order offenses (45.8%, which includes violations of probation and parole).13

In any case, re-arrest rates are not the best metric for measuring recidivism. Arrest does not suggest conviction or even actual guilt; of all recidivism measures, re-arrest casts the widest net. Although there is no comparable national estimate, data points from around the country show that remarkably few people convicted of violence return to prison after release:

- In Michigan, Safe and Just Michigan examined the re-incarceration rates of people convicted of homicide and sex offenses paroled from 2007 to 2010. They found that more than 99% did not return to prison within three years with a new sentence for a similar offense. Of the 820 people convicted of homicide released on parole, only two (0.2%) were convicted of another homicide.

- A recent study of people released from prison in New York and California between 1991 and 2014 found that only 1% of those convicted of murder or nonnegligent manslaughter were re-incarcerated for a similar offense within three years. The re-incarceration rate was even lower for older people: only 0.02% of people over 55 returned to prison for another murder or nonnegligent manslaughter conviction.

- In Maryland, a 2012 court case (Unger v. Maryland) lead to the release of nearly 200 people convicted of violent crimes who had been incarcerated since 1981 or earlier. As of 2018, only five had been returned to prison for violation of parole or a new crime. “The Ungers” were released with robust social support, underscoring the effectiveness of community-based programs and services in preventing future offending.

These data are especially remarkable given that people released from prison for a violent or sexual offense face additional conditions, restrictions, and resistance from society. Any allegation — no matter how slight — will be met with the most serious response. For example, failing to report something as simple as a job or housing update can lead to revocation of parole and a return to incarceration.

4. People who commit violent crimes are often themselves victims

Although people tend to view perpetrators and victims of violent crime as two entirely separate groups, people who commit violent crime are often themselves victims of violence and trauma — a fact behind the adage that “hurt people hurt people.” And many more people convicted of violent offenses have been chronically exposed to neighborhood and interpersonal violence or trauma as children and into adulthood. As the Square One Project explains, “Rather than violence being a behavioral tendency among a guilty few who harm the innocent, people convicted of violent crimes have lived in social contexts in which violence is likely. Often growing up in poor communities in which rates of street crime are high, and in chaotic homes which can be risky settings for children, justice-involved people can be swept into violence as victims and witnesses. From this perspective, the violent offender may have caused serious harm, but is likely to have suffered serious harm as well.”

Research bears this out:

- 68% of incarcerated people sampled in New York prisons reported some form of childhood victimization.

- Similarly, over 90% of youth in the Cook County (Chicago), IL juvenile detention facility reported that they had experienced one or more traumas.

- One-third of adults in Arkansas prisons report witnessing a murder, 40% of whom witnessed it while under the age of 18. An additional 36% reported that they have been seriously beaten or stabbed prior to their incarceration.

- In a sample of incarcerated men, researchers found that the PTSD rates were ten times higher than the rates found in the general male population (30-60% vs. 3-6%).

Other individual risk factors for violence, such as substance use disorders, shame, and isolation, may also be related to a history of victimization. Substance abuse, in particular, is strongly linked with past trauma, and research has found that a significant number of people who commit violence offenses are under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of offense.

While past victimization does not excuse violent behavior, it is certainly a mitigating factor. Moreover, it is further evidence that violence is not inherent, but rather a context-dependent behavior that can change with intervention. Yet past victimization is rarely taken into account at sentencing, as the system tends to respond according to offense categories rather than individual events and circumstances, and once in prison, people rarely receive trauma-informed programming.

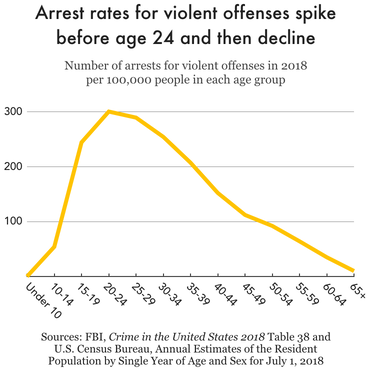

5. People age out of violence, so long sentences are not necessary for public safety

Furthermore, researchers have consistently found that age is one of the main predictors of violence. “Violent” is not a static characteristic, rather one’s risk for violence is highly dependent on their age. As people change over time, their risk for violence also changes.

It’s a well-established fact that crime tends to peak in adolescence or early adulthood and then decline with age, yet we incarcerate people long after their risk for violence has diminished. The “age-crime curve” can be explained in part by the fact that brain development continues well into people’s twenties, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, which regulates impulse control and reasoning. As a paper by the Executive Sessions at Harvard Kennedy School explains, “Young adults are more likely to engage in risk-seeking behavior, have difficulty moderating their responses in emotionally charged situations, or have not fully developed a future-oriented method of decision-making.” It can also be explained by social and personal factors, such as finding a stable career, getting married, and overcoming past traumas.

The age-crime curve is especially important because nearly 40% of people serving the longest prison terms were incarcerated before age 25. By issuing such lengthy sentences for young people convicted of violent crime, we are also ignoring their great potential for personal transformation and rehabilitation. Such excessive sentences have diminishing returns and, ultimately, opportunity costs to individuals, communities, and taxpayers.

Many of the reforms we found that exclude violent offenses have to do with expanding opportunities for earlier release. It is especially egregious that many states categorically exclude people convicted of violence from geriatric parole and compassionate release, since most people incarcerated long enough to grow old in prison were given long sentences for violent offenses. Incarcerating people that are old and/or terminally ill is unnecessarily punitive without benefiting public safety.

6. Many risk factors for violence are related to social and community conditions, not individual attributes

Many key risk factors for violence are related to social and community conditions, not individual attributes. Poverty, inequality, high unemployment, high rates of neighborhood change, and lack of educational and economic opportunities all contribute to violence in communities. Criminologists point to community factors like “low social cohesion” and “social disorganization” that can increase risk of violence. Many of these factors can be mediated through community investments, as most victims of crime would prefer.

There are better ways to respond to violence than incarceration

Locking people up for decades is an ineffective and inhumane response to violence, and states need to think beyond incarceration when addressing violence. The evidence shows that people convicted of violent offenses can be safely included in existing alternatives to incarceration. Moreover, states should take a proactive approach and invest in violence prevention rather than simply responding to violence.

People convicted of violence should be included in alternatives to incarceration

The United States overwhelmingly responds to violence with incarceration, so there is unfortunately limited research available on alternatives to incarceration for people convicted of violent offenses. The preliminary research, however, shows that existing alternatives to incarceration, such as probation and problem-solving courts, can be effective responses to violence. Communities around the country are also developing other innovative alternatives to incarceration, which can enhance public safety with lower social and fiscal costs than incarceration, and with fewer collateral consequences. At a minimum, states should ensure that people convicted of violent offenses are not categorically excluded from these alternatives:

- Probation can be an effective alternative to incarceration for people convicted of violent offenses but often is not even considered as a sentence for them. In 2016, 20% of people on probation had been convicted of a violent offense. The use of probation for violent offenses could be expanded further without sacrificing public safety. Researchers recently looked at a group of people convicted of violent offenses between 2003 and 2006 who were “on the margin” between probation and prison. Following these individuals through 2015, they found that people sentenced to prison were no less likely to be arrested or convicted of another violent crime than those sentenced to probation. (Of course, we should not replace de facto life sentences with de facto life probation terms that keep people on an endless tightrope, without regard to their compliance and changes over time.)

- Problem-solving courts are another alternative that are typically unavailable to people accused of violent offenses. These courts address some of the root causes of violent offending, such as substance use, and they’ve been shown to be an effective alternative to incarceration for people accused of violent offenses. Drug courts divert people with substance use disorder, a major contributor to violence, from jails and prisons to community-based treatment.14 A 2011 drug court evaluation found that people with histories of violent behavior showed a greater reduction in crime compared to other participants. And in a 2014 study of the Brooklyn Mental Health Court, where 55% of defendants were charged with a violent felony, mental health court participants were significantly less likely to be re-arrested and re-convicted compared to a matched sample of incarcerated people with mental illness. Most notably, researchers found that those convicted of “serious (felony) offenses” were less likely to be re-arrested and break the rules of their supervision.

- Community-based programs run by nonprofit organizations are newer alternatives to incarceration, but also typically exclude people convicted of violent offenses. The most notable exception is Common Justice, an alternative to incarceration and victim service program based on restorative justice principles that specifically targets violent offenses. The program operates restorative justice circles wherein responsible parties engage in a facilitated conversation with those they have harmed, who then have a say in what consequences are appropriate. Such consequences can include community service, restitution, and commitments to attend school and work. Once the circle determines appropriate consequences, the Common Justice program monitors responsible parties’ adherence and supervises their completion of a 12-15-month violence intervention program.1516

Communities should invest in violence prevention, not incarceration

By advocating for reducing the number of people incarcerated for violent offenses, we are not suggesting that violence not be taken seriously. On the contrary, we suggest that states invest more heavily in violence prevention strategies that will make a more significant and long-term impact on reducing violence.

The current response to violence in the United States is largely reactive, and relies almost entirely on incarceration. This has inflicted enormous harms on individuals, families, and communities without yielding significant increases in public safety. Rather than simply reacting to violence with incarceration, policymakers should focus on preventing violence in the first place. This can be done through investing in community-driven safety strategies, adopting a public health approach to violence, and designing interventions directed at youth.

Investments in social services and communities can reduce violent crime rates in communities — and that means investments beyond beefing up law enforcement. Fourteen million students attend schools that have on-site police, but no counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker. States and communities looking to prevent violence should invest in the things people need to thrive:

- Increase access to healthcare, especially substance use disorder treatment;

- Clear vacant lots and repair blighted buildings, where the local community supports that strategy;17

- Improve neighborhood infrastructure, including street lighting, illuminated walk/don’t walk signs, painted crosswalks, public transportation, and parks;

- Invest in community non-profits focused on addressing violence and building stronger communities; and

- Increase access to quality education.

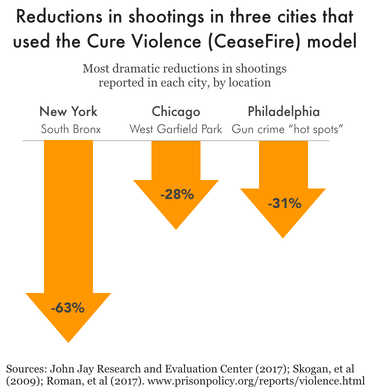

For Chicago and Philadelphia, this chart shows the reduction in shootings directly attributable to the program, accounting for decreases in shootings in comparison sites over the same time. For New York, it shows the total reduction in shootings. Shootings also dropped in other sites, but those were more modest changes.

Adopting a public health approach to violence can lead to significant reductions in crime. Because exposure to violence significantly increases the likelihood that someone will act violently, the Cure Violence (formerly CeaseFire) model reduces the spread of violence using the methods and strategies associated with disease control: detecting and interrupting potentially violent conflicts, identifying and treating those who are most likely to engage in violence, and mobilizing the community to change norms. The model has been implemented in more than 25 sites in the United States, and has led to dramatic reductions in violence in places such as New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

Communities can also develop interventions targeted at youth to mitigate the increased likelihood of violent offending among young people. These strategies can address the social and behavioral factors that increase young people’s risk for violence. For example:

- A summer youth employment program in Boston reduced charges for violent crime by 35%;

- The mentoring program Becoming a Man, which uses cognitive behavioral therapy to reduce impulsive decisions among youth, reduced violent crime arrests by half during program participation; and

- In Chicago, the Choose to Change (C2C): Your Mind, Your Game program targets youth ages 13-18 that may be actively, or at risk of becoming, gang involved. The program provides youth with mentoring and trauma-informed cognitive behavioral therapy aimed at addressing past trauma and developing a new set of individual decision-making tools. The program has reduced arrests for violent crime of young people by almost 50% with sustained results.

All of these strategies illustrate that proper investments can lead to sharp decreases in violent crime. Instead of continuing to funnel money into long sentences, which do not increase public safety, states should minimize their use of incarceration and invest the cost savings into violence prevention.

Conclusion

Categorically excluding people convicted of violent offenses seriously undermines the impact of otherwise laudable criminal justice reforms. Troublingly, these carve-outs also demonstrate policymakers’ reluctance to make better choices, based on current evidence, than their “tough on crime” era predecessors. In order to dramatically reduce prison populations and make our communities safer, federal and state legislators must roll back counterproductive, draconian penalties for both violent and nonviolent offenses, and invest in alternatives to incarceration and violence prevention strategies that can effect real change.

Recommendations

In order to reduce prison populations and to address the root causes of violence, state and local governments should:

- Repeal policies that have led to excessive sentences for the large number of people incarcerated for violent offenses, including truth-in-sentencing laws, mandatory minimum sentences, “three strikes” laws, and laws restricting release on parole. These changes should also be applied retroactively.18

- Include people convicted of violent offenses in future criminal justice reforms, such as laws allowing them to participate in problem solving courts, earn more “good time” while incarcerated, and receive medical and geriatric parole.

- Direct people accused of violent offenses to problem solving courts, which can address the root causes of violent behavior. Research has shown that mental health courts can reduce the likelihood of re-arrest for any new charge, including violence, and drug courts can help people whose violent behavior is related to an underlying substance use disorder.

- Supervise more people convicted of violent offenses in the community instead of putting them in prison. People convicted of violent offenses should be eligible for probation in lieu of incarceration, and parole can allow people who have already been incarcerated to serve the remainder of their sentence in the community. States must tread carefully, however, and ensure that these alternatives to incarceration don’t end up funneling people back into prison.

- Implement policies that make more people eligible for parole, and sooner, including presumptive parole and “second look” sentencing. With presumptive parole, incarcerated individuals are released upon first becoming eligible for parole unless the parole board finds explicit reasons to not release them. Under “second look” sentencing, long sentences are automatically reviewed by a panel of retired judges after 15 years, with an eye toward possible sentence modification or release, and for subsequent review within 10 years, regardless of the sentence’s minimum parole eligibility date.

- Invest in evidence-based rehabilitative programs in prisons to address the underlying causes of violence, such as trauma or substance use disorder.

- Invest in robust re-entry services so people can succeed once released from a lengthy prison sentence for a violent offense, as exemplified by the release of “the Ungers.”

- Invest in violence prevention strategies, rather than relying on incarceration as the only response to violence. Because violence is cyclical, with victims engaging in violence themselves, resources should be redirected to disrupting the cycle over the long term, with interventions and community investments that target the factors that contribute to violence in the first place.

Appendix

| Alabama | AL H 348 (2010): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from drug courts AL S 481 (2011): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from a local pretrial diversion program AL S 67 (2015): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from probation and parole reforms, including: requiring parole reconsideration 2 years after denial, setting a maximum of 45 days of incarceration for rule violations, and the removal of the requirement that incarcerated people serve the lesser of ten years or one third of their sentence before release |

| Alaska | H.B. 49 (2019): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving earned compliance credits |

| Arizona | AZ S1213 (2012): Excludes people convicted of domestic violence from participating in the Department of Corrections transition program |

| Arkansas | AR H 1470 (2017): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from the pre-adjudication probation programs authorized by this legislation |

| California | CA S 1266 (2010): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from participating in an alternative to incarceration program designed for women who are pregnant or who were primary caregiviers of dependent children immediately prior to incarceration. CA A 2124 (2014): Excludes people accused of violent offenses from participating in a pilot deferred sentencing program in Los Angeles |

| Colorado | CO S 250 (2013): Excludes people with prior convictions for violent offenses from having felony convictions involving drug possession vacated CO S 123 (2013): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving court relief for collateral consequences when sentenced to probation, a community corrections program, deferred prosecution, or another alternative sentence |

| Connecticut | CT H 7104 (2015): Excludes people eligible for parole that are convicted of violent offenses from receiving parole without a hearing CT H 7027 (2015): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from earning risk reduction credits to reduce their sentences |

| Delaware | DE S 226 (2012): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving probation length reductions DE H 102 (2019): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses who are victims of sex trafficking from receiving vacatur and expungement of offenses |

| Florida | FL H 5001 (2010): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from the Alternative Sentencing Program, which diverts people to residential and outpatient treatment programming, day reporting, community support, employment assistance, life-skills counseling and other services to reduce recidivism Amendment 4 (2018): Excludes people convicted of murder and sex offenses from having their voting rights restored after they complete their sentence |

| Georgia | GA S 365 (2014): Prevents people convicted of serious violent felonies from recieving Program and Treatment Completion Certificates, which recognizes a person’s achievements toward successful reentry into society GA H 328 (2015): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from being eligible for early parole even if they have served at least 12 years, have a low-risk recidivism rating, are classified as a medium or lower prison security risk, have completed program requirements that were determined by a risk assessment, have completed an education or job skills training program and have not violated any serious disciplinary violations in the preceding 12 months |

| Hawaii | HI S 2776 (2012): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from automatically receiving parole if they are identified as low risk by a parole risk assessment |

| Illinois | IL H 5214 (2010): Excludes people charged with violent offenses and anyone who was imprisoned for violent offenses in the past 10 years from veterans court IL S 3349 (2012): Excludes people charged with violent offenses from offender initiative probation program IL S 3458 (2012): Excludes people convicted of many violent offenses from receiving certificate of eligibility for sealing of a criminal record IL H 3010 (2013): Excludes people with past convictions for violent offenses from receiving probation for certain class 4 felony drug and theft crimes IL S 3267 (2014): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses on probation or conditional discharge from earning sentence credits for completing educational and job training programs IL S 3164 (2016): Excludes people with past convictions for violent offenses from presumptive parole |

| Indiana | IN H 1211 (2011): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from being able to petition the court to restrict disclosure of arrest records IN H 1006 (2013): Makes certain felonies involving violence or deadly weapons ineligible for a community corrections sentence |

| Iowa | H.F. 2064 (2016): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses who are deemed low risk from being eligible for parole after completing half their sentences |

| Kansas | SB 14 (2007): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving time credits for good behavior |

| Kentucky | KY H 1 (2010): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from a law designed to reduce length of incarceration and assist with re-entry Executive Order 2019-003: Restores voting rights for people who have completed their sentences, but only applies to people convicted of non-violent offenses |

| Louisiana | LA S 312 (2010): Excludes people convicted of certain violent offenses convicted on or after January 1, 1992 from receiving reduction of sentence for good behavior LA H 563 (2010): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from electronic monitoring home incarceration program LA H 138 (2011): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses who have served at least 10 years in prison and who are at least 60 years old from receiving parole consideration LA H 416 (2011): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving parole eligibility after serving 25% of their sentence LA H 543 (2012): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses sentenced to life imprisonment from becoming eligible for parole LA H 228 (2012): Excludes “habitual offenders” convicted of violent offenses from earning good time for participating in certified treatment and rehabilitation programs LA S 71 (2013): Excludes people with convictions for violent offenses within the past 10 years from mental health courts LA H 442 (2013): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from substance abuse probation program LA H 1022 (2016): Excludes people convicted of certain violent offenses from having their mandatory minimum sentence suspended and being placed under the supervision of a re-entry court after completing a rehabilitation and wokrforce development program |

| Maryland | SB 1005 (2016): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving administrative release if they have served a minimum amount of time and have complied with the prison case plan |

| Massachusetts | H. 4012 (2018): Excludes people convicted of certain drug offenses, and those that used violence in the commission of drug offenses from earning sentence deductions, parole eligibility, and work release until they have served their mandatory minimum sentence |

| Michigan | MI H 5162 (2012): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from veteran treatment courts MI H 4694 (2013): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from mental health courts |

| Minnesota | MN SF 3481 (2016): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from a conditional release program for drug offenders |

| Mississippi | MS H 835 (2010): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from pilot community corrections programs MS S 2731 (2012): Excludes bedridden people convicted of violent offenses from receiving conditional medical release |

| Missouri | HB 547 (2019): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from participating in veterans’ treatment courts |

| Nevada | AB 236 (2019): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving geriatric parole |

| New Jersey | N.J.S.A. 30:4-123.51c (2017): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving medical parole |

| New Mexico | HB 342 (2019): Excludes people with prior convictions for violent offenses from participating in a pre-prosecution diversion program |

| New York | N.Y. A.N. 156 (2009): Excludes people convicted of several types of violent offenses who are ineligible for good time from receiving 6 months off their minimum sentence N.Y. S.N. 2812 (2011): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving a merit termination of supervision |

| North Carolina | N.C. H.B. 198 (2019): Authorizes expungement of felony convictions for victims of human trafficking, except for violent offenses N.C. H.B. 770 (2019): Prevents licensing boards from denying an applicant a license because they have a criminal record unless applicant’s criminal conviction history is directly related to the duties and responsibilities for the licensed occupation, except for people convicted of violent offenses |

| North Dakota | ND S 2141 (2011): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving performance-based sentence reductions |

| Oklahoma | OK H 2998 (2010): Excludes people accused of violent offenses from participating in a pilot diversion program for primary caregivers of minors OK S 578 (2015): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses who are terminally ill or progressively debilitated to be considered for parole to a private long-term care facility |

| Oregon | Act No. 25 (2010): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from diversion programs designed for veterans and active duty military |

| Pennsylvania | PA S 100 (2012): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from probation reforms in this legislation |

| Rhode Island | RI S 358 (2013): Excludes people convicted of some violent offenses from petitioning the parole board for a certificate of recovery and re-entry, which serves as a determining factor for obtaining employment, professional licenses, housing and other benefits |

| South Carolina | SC S 426 (2015): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from pre- and/or post-adjudicatory mental health court programs authorized by this legislation |

| Tennessee | SB 985 (2019): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses who are the primary caretaker of a child from alternative to incarceration program |

| Texas | TX H 1205 (2011): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving time credits for community supervision TX H 1188 (2013): Prohibits lawsuits from being brought against an employer solely for negligent hiring or failing to adequately supervise an employee based on evidence that the employee has been convicted of a criminal offense, unless that offense is violent TX S 1902 (2015): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from expanded nondisclosure of criminal records upon successful completion of community supervision |

| Utah | UT H 21 (2010): Excludes many people convicted of violent offenses from expungement reforms |

| Vermont | H 460 (2019): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses who are victims of sex trafficking from receiving vacatur and expungement of offenses |

| Washington | WA H 1718 (2011): Excludes people charged with violent offenses with developmental disability or traumatic brain injury from participating in mental health courts SB 5990 (2003): Excludes people convicted of violent offenses from receiving increased earned time WA S 5107 (2015): Excludes people charged or convicted of violent or sex offenses, including vehicular homicide and firearms offenses from problem solving courts |

| West Virginia | WV S 371 (2013): Excludes people convicted of violence offenses from participating in a drug treatment alternative to incarceration program |

For more on this legislation, see our expanded appendix.

Methodology

The vast majority of examples of criminal justice reforms excluding people convicted of violent offenses were collected using the National Conference of State Legislatures’ Statewide Sentencing and Corrections Legislation database. We also relied on news sources and publications by other criminal justice organizations, and collected examples from state-based advocates.

Acknowledgments

All Prison Policy Initiative reports are collaborative endeavors, and this report is no different, building on an entire movement’s worth of research and strategy. This report benefitted from the expertise and input of many individuals, including Bruce Reilly and Shaena Fazal. I thank all of the advocates and state leaders who shared examples of reforms in their states that excluded people accused or convicted of violent offenses. Finally, I am also indebted to Wendy Sawyer for her guidance throughout the research and writing process and for making the graphics, to Peter Wagner for his feedback, and to Roxanne Daniel for her research support.

About the author

Alexi Jones is a Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. Since joining the Prison Policy Initiative, Lexi has authored Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and supervision by state and Does our county really need a bigger jail? A guide for avoiding unnecessary jail expansion, which outlines more just and humane ways for jails to address overcrowding than jail expansion. She has also co-authored State of Phone Justice: Local jails, state prisons, and phone providers with Peter Wagner and Arrest, Release, Repeat: How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems with Wendy Sawyer.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. Through accessible, big-picture reports, the organization helps the public engage more fully in criminal justice reform. Its 2018 report Eight Keys to Mercy: How to shorten excessive prison sentences helped popularize strategies for reducing the prison population without discriminating based on offense type. More recently, it published Failure should not be an option: Grading the parole release systems of all 50 states, which outlines how states around the country fail to offer incarcerated people meaningful opportunities for release. The Prison Policy Initiative also leads the nation’s fight against prison-based gerrymandering and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone and video calling industries.

Footnotes

In fact, violent crimes rates are near historic lows. ↩

It is important to note that what constitutes a “violent crime” varies from state to state. An act that might be defined as violent in one state may defined as nonviolent in another. Moreover, sometimes acts that are considered “violent crimes” do not involve physical harm. For example, as The Marshall Project explains, in some states entering a dwelling that is not yours, purse snatching, and the theft of drugs are considered “violent.” The Justice Policy Institute explains many of these inconsistencies, and why they matter, in its report Defining Violence. However, our report focuses on the more fundamental question of how we respond to violence, rather than attempting to clarify who belongs in the “nonviolent” category. ↩

In this report, we generally use the phrase “convicted of violent offenses” unless a given criminal justice reform affects defendants pretrial, and excludes people based on the offense they are accused of. It is also important to note that some of the reforms displayed in the map (even if they are pretrial) exclude people based on whether they have a past violent conviction. ↩

People convicted of sex offenses, much like people convicted of violence, are often excluded from criminal justice reforms. This is despite the fact “sex offenses,” like “violent offenses,” encompass a wide range of behaviors, and also have among the lowest recidivism rates. ↩

We calculated this figure using data from the National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP), 1991-2015. Although HB 585 grants eligibility to people who are 60+, this 5,700 reflects the number of people who are 55+, as that is how age was categorized in the NCRP. ↩

Similarly, over ten years ago Rhode Island voters passed an amendment that restored voting rights to all people with past felony convictions, regardless of whether they committed violent or non-violent offenses, demonstrating that including people convicted of violent offenses is possible even when voters are voting directly on the issue. In contrast, Florida voters passed Amendment 4 in 2018, which restored voting rights for people with felony convictions who have completed all the terms of their sentence, with the exception of people convicted of murder and sex offenses. ↩

These reforms ultimately had a limited impact due to a lack of funding and poor implementation. While prison populations initially dropped, they have been steadily increasing over the past few years, largely due to probation and parole revocations. This example underscores that states must do more than pass criminal justice reforms; they must also ensure that they are implemented and funded properly. ↩

An additional 44,311 individuals are serving “virtual life” sentences of 50 years or more. ↩

This is despite the fact that the United States is home to 5% of the world’s population. ↩

For more, see: (1) National Research Council (2012). Deterrence and the Death Penalty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; (2) National Research Council (1993). Understanding and Preventing Violence: Volume 1. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; (3) Steven N. Durlauf and Daniel S. Nagin, Imprisonment and crime: Can both be reduced?; and (4) Nagin, D.S. (2013). “ Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century,” Crime and Justice 42: 199-263. ↩

The recidivism rate for people convicted of violent offenses appears much higher when defined as re-arrest, which, as a measure, casts the widest net but does not suggest conviction nor actual guilt. But even using re-arrest, people convicted of violent offenses are less likely to be re-arrested in the years after release than those convicted of property, drug, or public order offenses. ↩

The BJS reports 9-year recidivism rates, but we opted to focus on 3-year recidivism rates, since that is a more standard time frame for measuring recidivism. ↩

Additionally, in her book, Life After Murder, Nancy Mullane looked at the arrest rates for 988 people convicted of murder who were released from California prisons from 1990 until May 2011 and found that not one was re-arrested for murder. ↩

According to a 2017 Bureau of Justice Statistics report, 14% of people serving sentences for violent offenses in state prisons and jails (2007-2009) reported committing the offense to get money for drugs. 40% of state prisoners — and 37% in jail — who were serving a sentence for violence reported using drugs at the time of the offense. ↩

Officials in Fulton County, GA developed My Journey Matters, an alternative sentencing program designed for people aged 16 to 29 accused of violent offenses. The initiative involves the district attorney’s office, the public defender’s offices, the probation department, and a county judge, and provides service and support to help people who have committed violent crimes rather than relying incarceration. The program is currently developing tools to track outcomes, but anecdotal evidence suggests the program is working. As Atlanta criminal defense attorney Ash Joshi explained, “All the clients I’ve had go through it are better now than before they went in. Something has improved in their lives. They’ve got a job. They’re more educated. They dress better. They talk better. They’re more respectful. They’re making better decisions.” ↩

There is no quantitative outcome data available yet, but a staggering 90% of victims given the choice between incarcerating the perpetrator of violence or participating Common Justice opted for the latter. ↩

It is crucial that this is done with community support and input, and that it doesn’t lead to displacement and gentrification of people in low income communities. ↩

Too often, sentencing reduction reforms only apply to future sentences and do not apply to the sentences of people currently incarcerated. By applying sentencing reforms retroactively, states can ensure that those who are currently incarcerated also benefit from sentencing reduction reforms, thereby allowing even further reduction of prison populations and ensuring that people who are currently incarcerated aren’t experiencing outdated punishments. ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.