2018 was another big year for powerful data visualizations from the Prison Policy Initiative. These are our 11 favorites.

by Wendy Sawyer,

December 28, 2018

2018 was another big year for powerful data visualizations from the Prison Policy Initiative. These are 11 of our favorites, in the order they appeared this year:

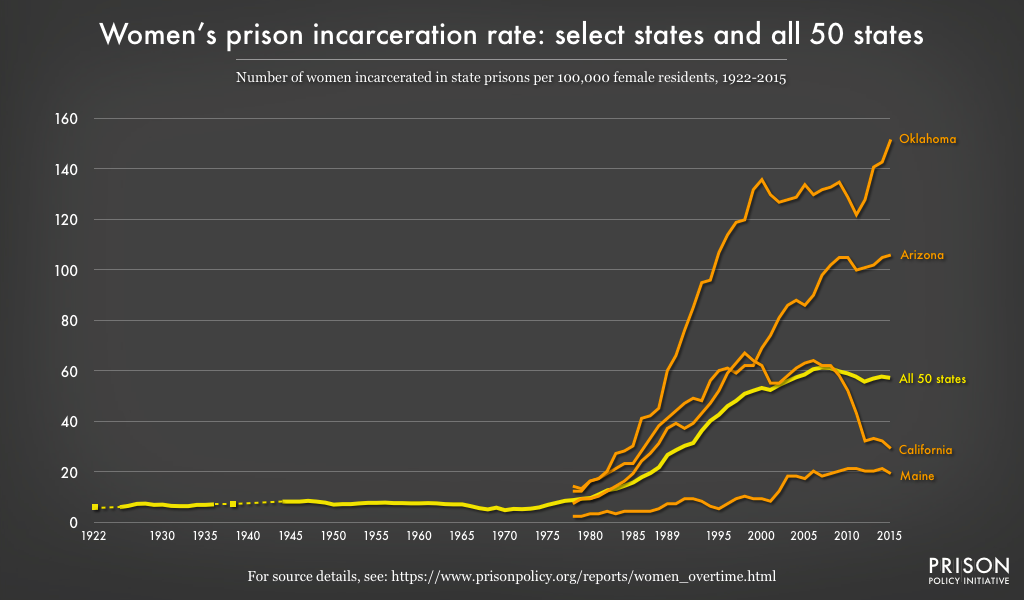

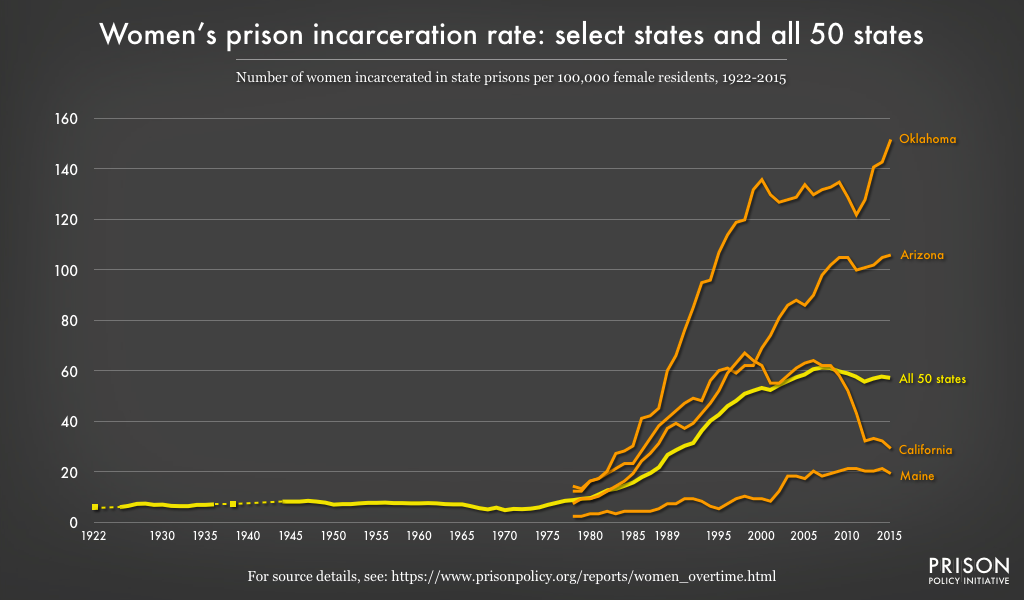

1. The Gender Divide

In January, we tracked women’s state prison growth as far back as 1922 to show that women’s incarceration today is historically unprecedented. Our report also shows that the national trend obscures even more dramatic state variation. For example, in 2016, Oklahoma’s female prison incarceration rate was more than double the national average, and six times the rate in Maine. We illustrated the scale of these variations by charting four disparate state trends alongside the national trend:

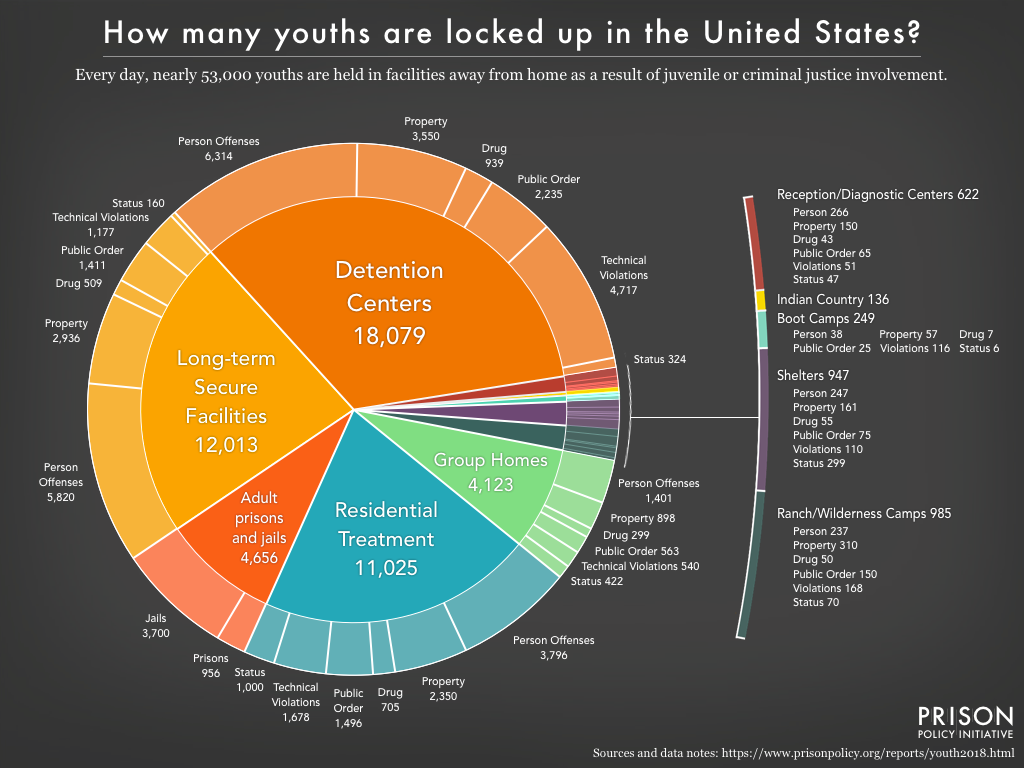

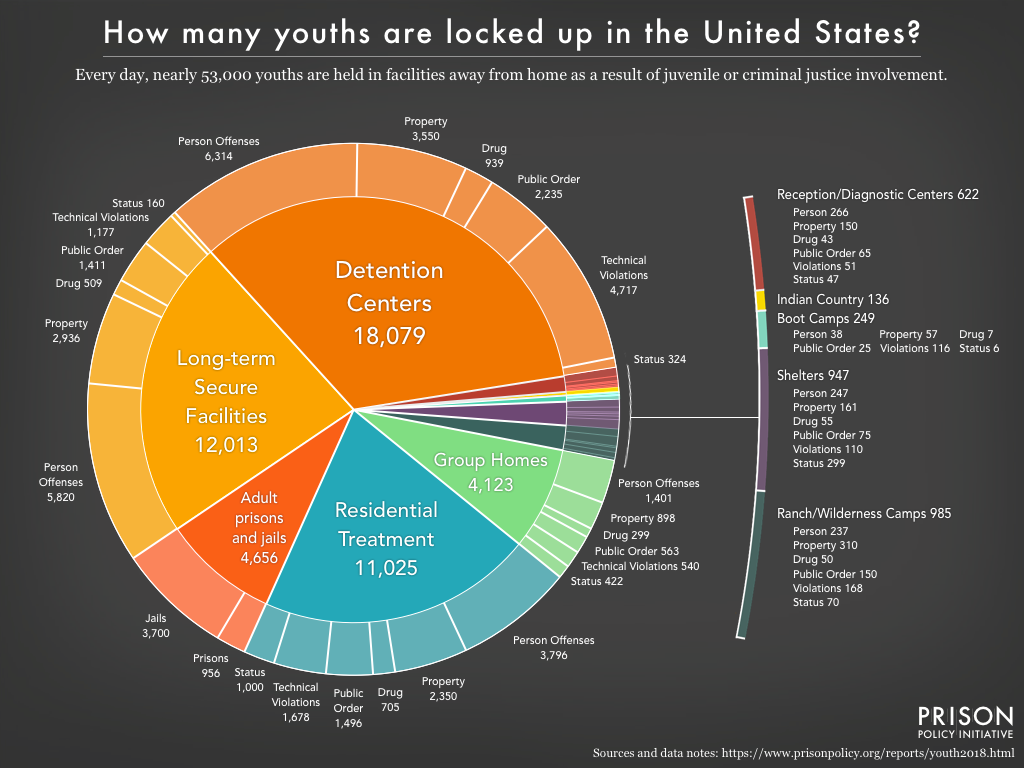

2. Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie

For the first time, we compiled data on youth confinement in both adult and youth facilities — using our “whole pie” approach — to show what happens when justice-involved youth are held by the state: where they are held, under what conditions, and for what offenses. We found that nearly one in ten of these youth are held in an adult prison or jail, and that most in juvenile “residential placement” are held in similarly restrictive, correctional-style facilities.

Other graphics in this report highlighted some of the problems of the adult criminal justice system that are mirrored in the juvenile justice system, including punitive conditions, pretrial detention, and overcriminalization.

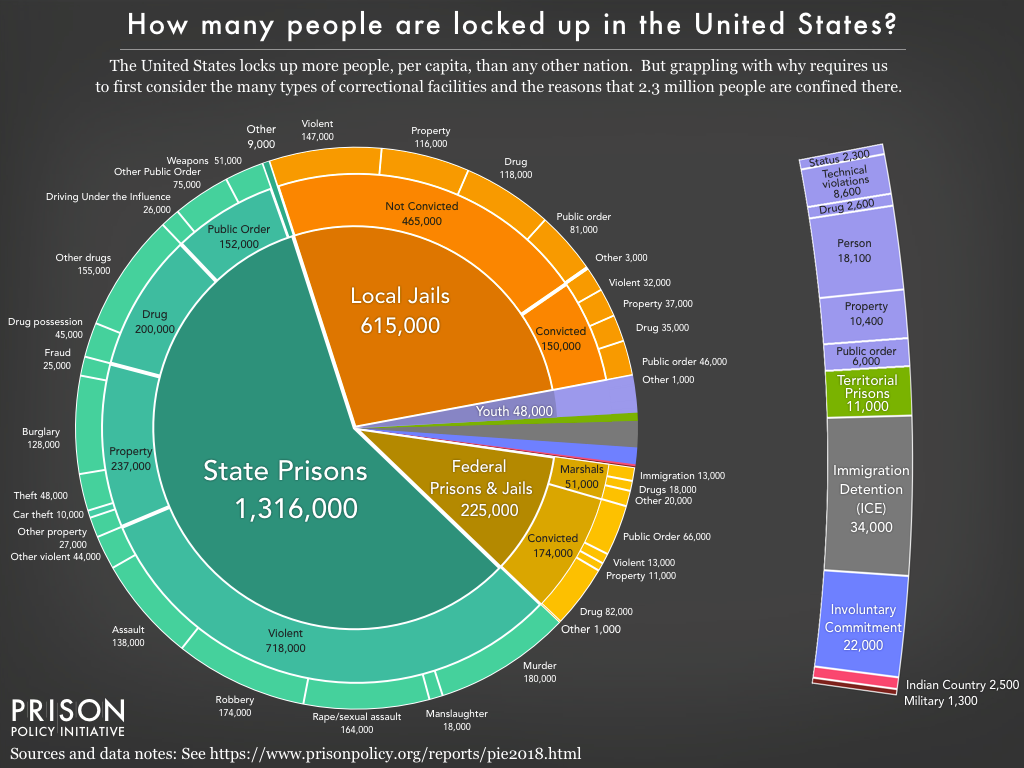

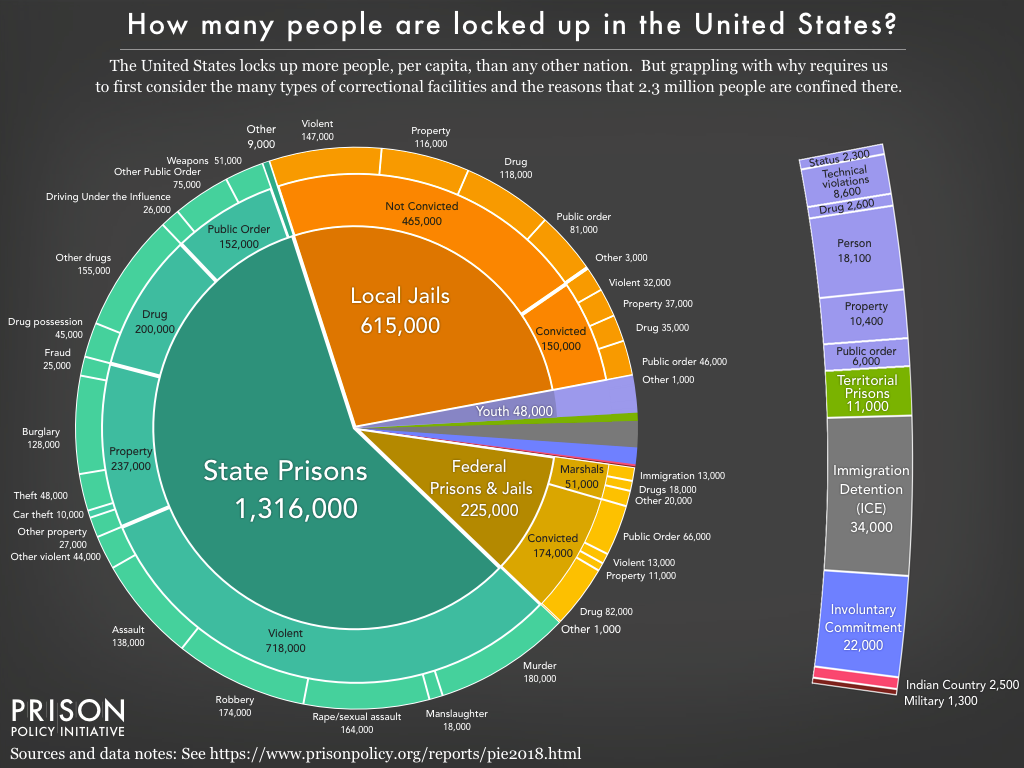

3. Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2018

Our fifth edition of our “Whole Pie” report — and our most widely-referenced data visualization — offers the most comprehensive view of U.S. criminal justice confinement to date.

This year, we were able to include the 51,000 individuals held by the U.S. Marshals Service in the federal “slice,” as well as over 15,000 people held in state psychiatric hospitals due to justice system involvement. In addition to refining our methodology, we created four slideshows with detailed views of parts of the “pie” that are often misunderstood or overlooked, including federal detention and incarceration, jails and pretrial detention, drug offenses, and more.

4. Artist collaboration: Visualizing 10.6 million annual jail admissions

Following closely on the heels of the “Whole Pie” report, we collaborated with data journalist and illustrator Mona Chalabi to visualize how much greater the impact of jails is than the daily population suggests. While 731,000 people are held in jails on a given day, people actually go to jail 10.6 million times each year in the U.S.

What do 10.6 million jail admissions look like? To show us, Mona drew one person in handcuffs to represent one jail admission. She then repeated the image, much smaller, 10.6 million times:

To get the full effect, click through to the original post and start scrolling.

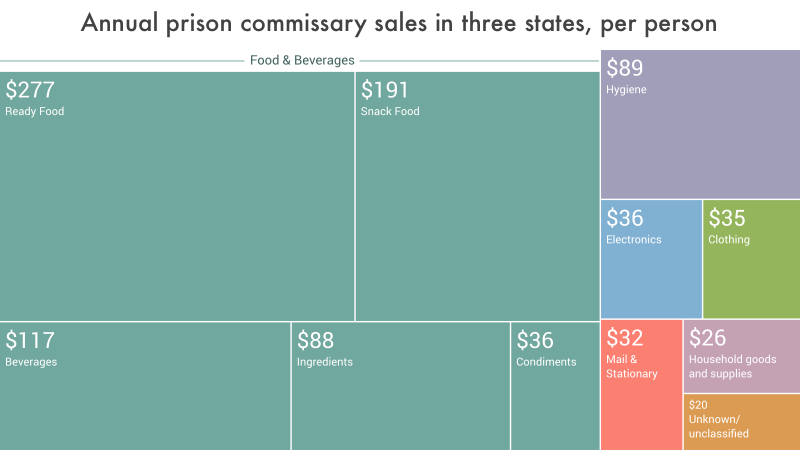

5. Showing that incarcerated people are buying necessities, not luxuries, in prison commissaries

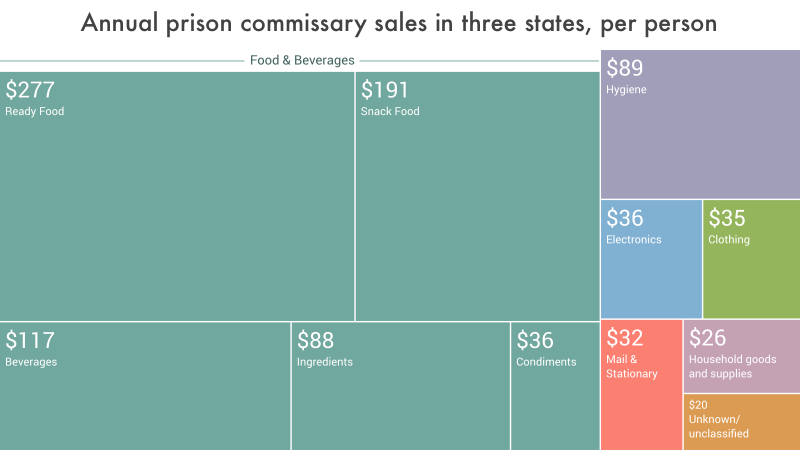

Prison commissaries are an essential part of prison life, but until this year, we didn’t have good data about how much items generally cost or what incarcerated people are buying. For the report The Company Store, Prison Policy Initiative volunteer Stephen Raher pored over commissary sales records from Illinois, Massachusetts, and Washington to find that incarcerated people in these states spent an average of $947 per person, per year, and that most of that money goes to food and hygiene products. We illustrated the breakdown of per capita commissary sales with a tree map for each state, and one showing the averages of all three states:

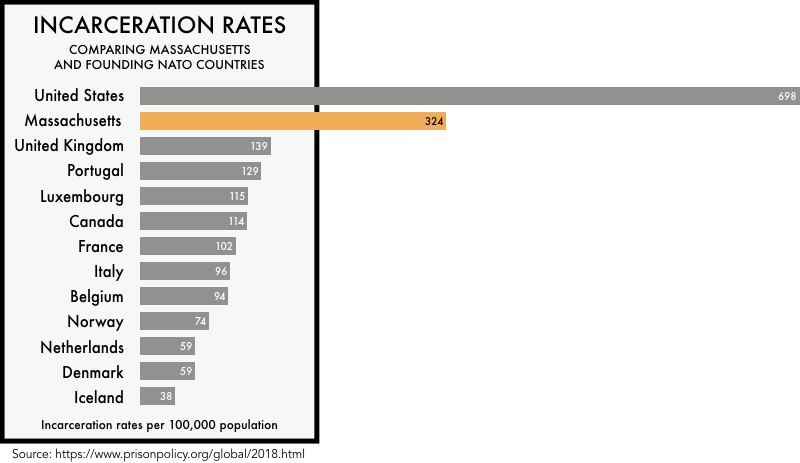

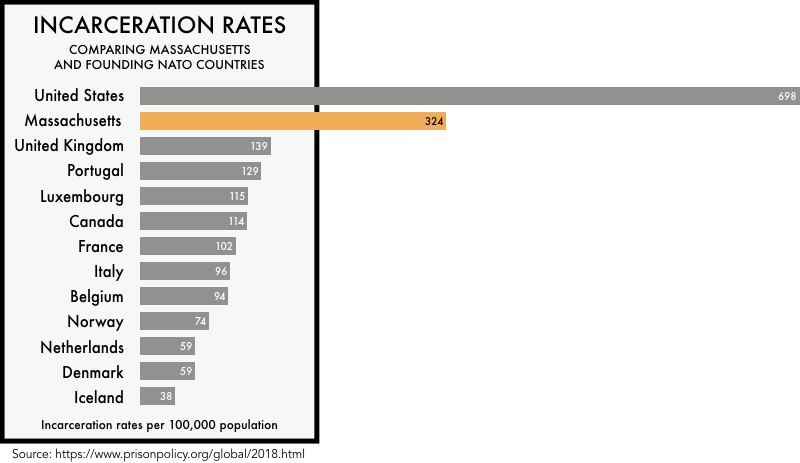

6. Putting state incarceration rates in the global context

In our 2018 updates to States of Incarceration: The Global Context and its companion report focused on women’s incarceration, we compared each state’s rate of incarceration to those of 166 other countries, revealing that about half of all U.S. states have higher incarceration rates than any independent country on earth. Even states that have embraced “progressive” criminal justice reforms (like Massachusetts, below) incarcerate people at far higher rates than other Western democracies. To illustrate this point, we also created individual state graphs comparing states to founding NATO countries:

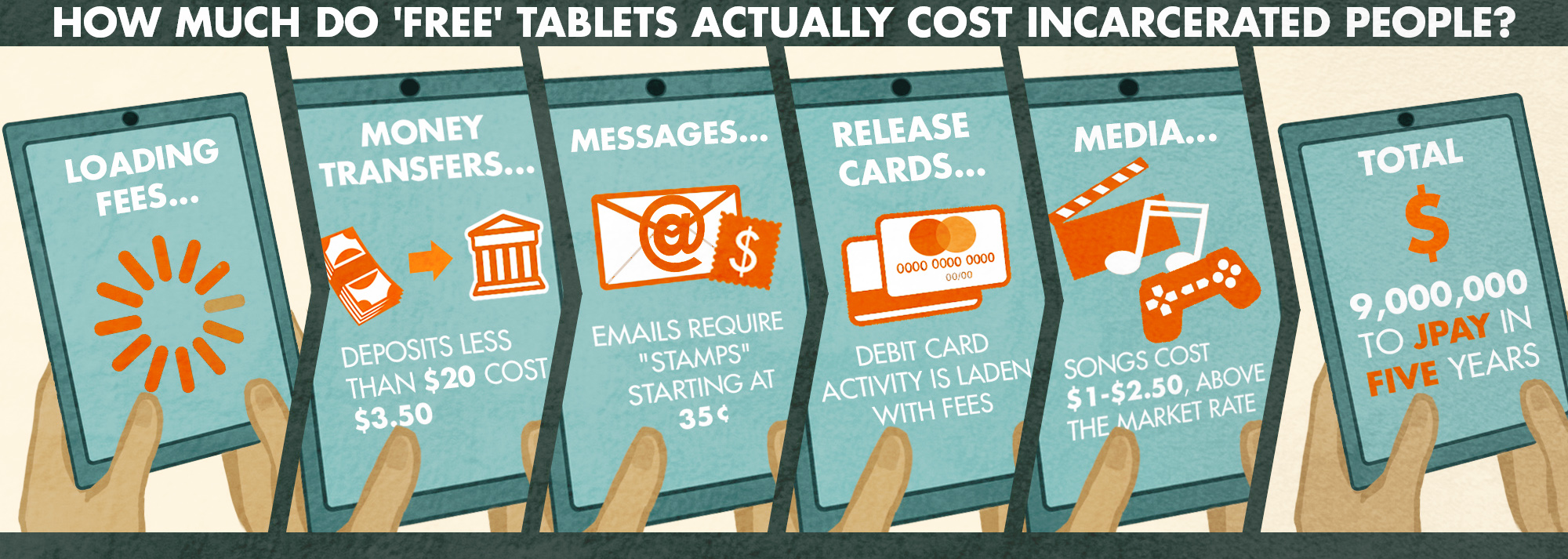

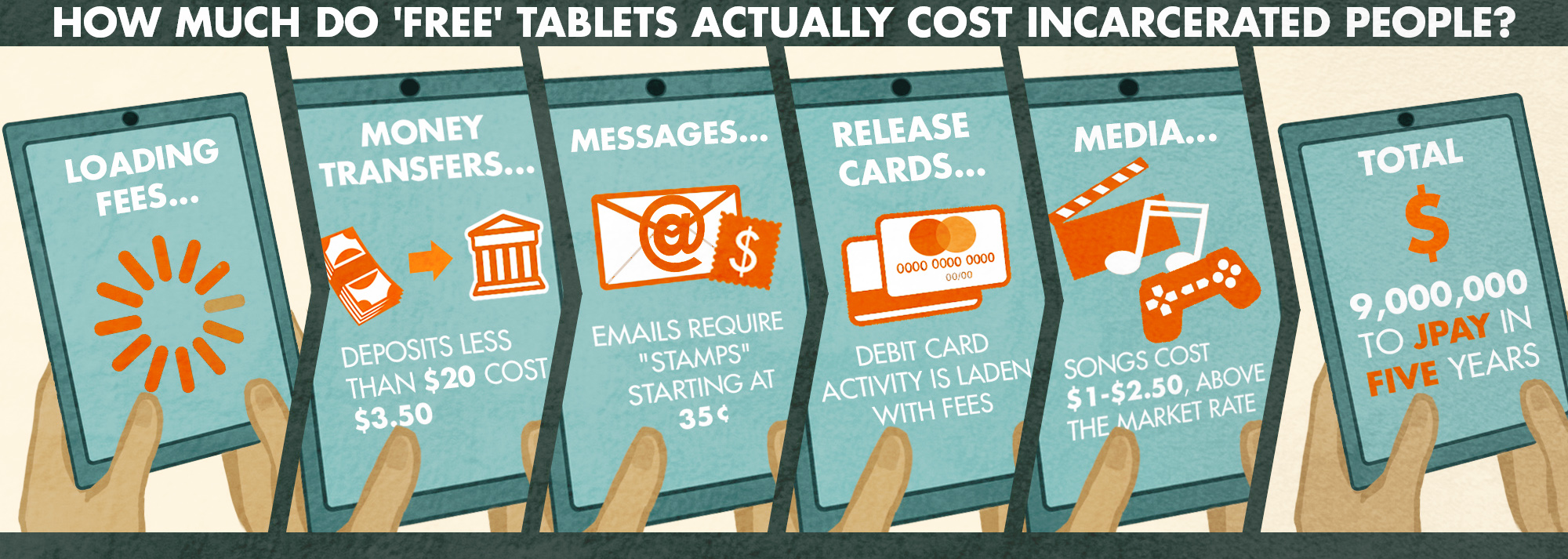

7. Showing the hidden costs in “free” tablet contracts

Illustrator Elydah Joyce artfully explained almost every scam we’ve documented in previous reports and how they were hidden within a “no cost” tablet contract between the New York State Department of Corrections and private company JPay:

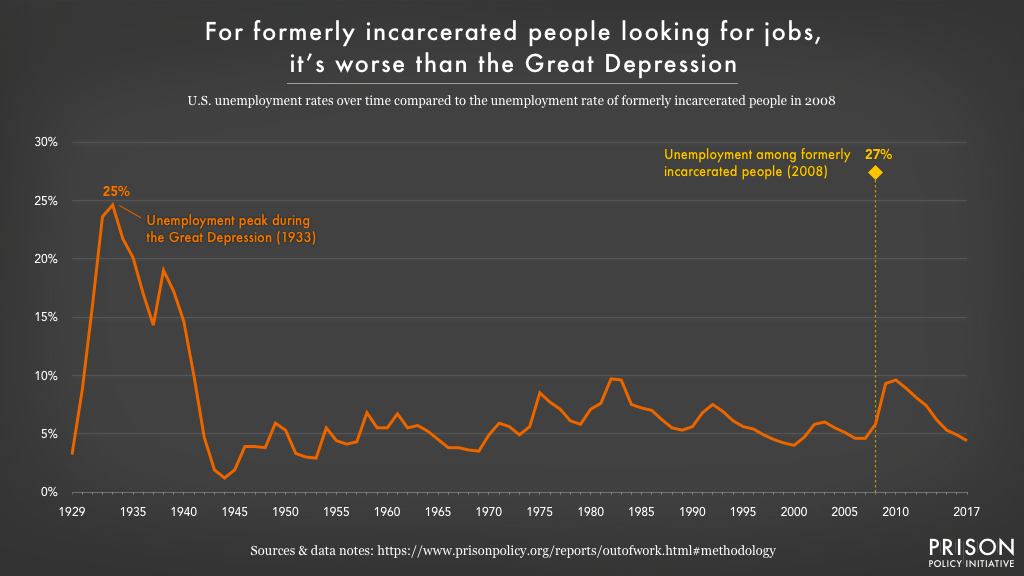

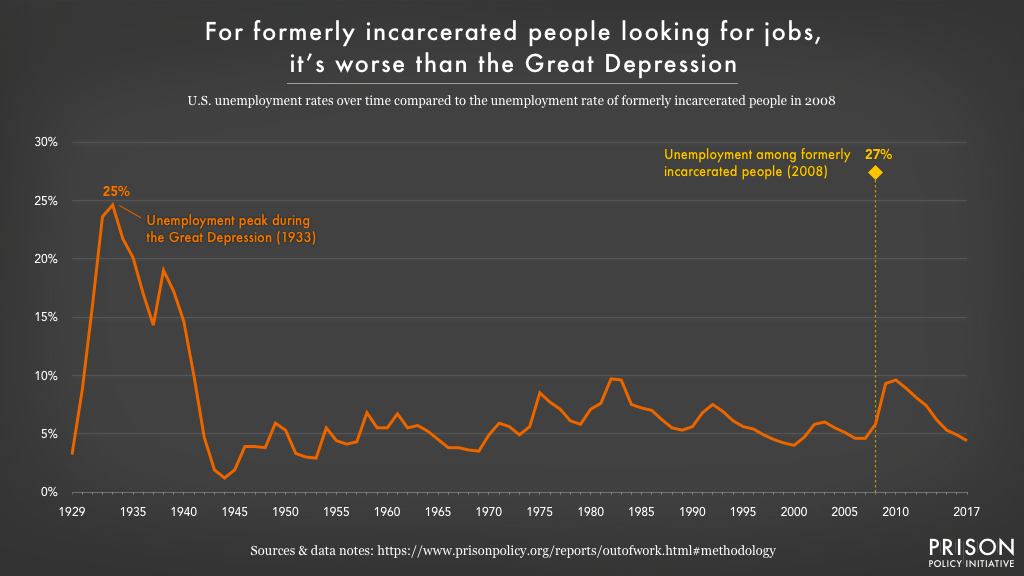

8. Comparing unemployment among formerly incarcerated people to the Great Depression

In Out of Prison & Out of Work, we calculated the first-ever national unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people: a staggering 27 percent. To put that in perspective, we charted the U.S. unemployment rate since 1929 to show that, for the 5 million formerly incarcerated people in the U.S., the odds of finding employment are worse than they were even at the peak of the Great Depression:

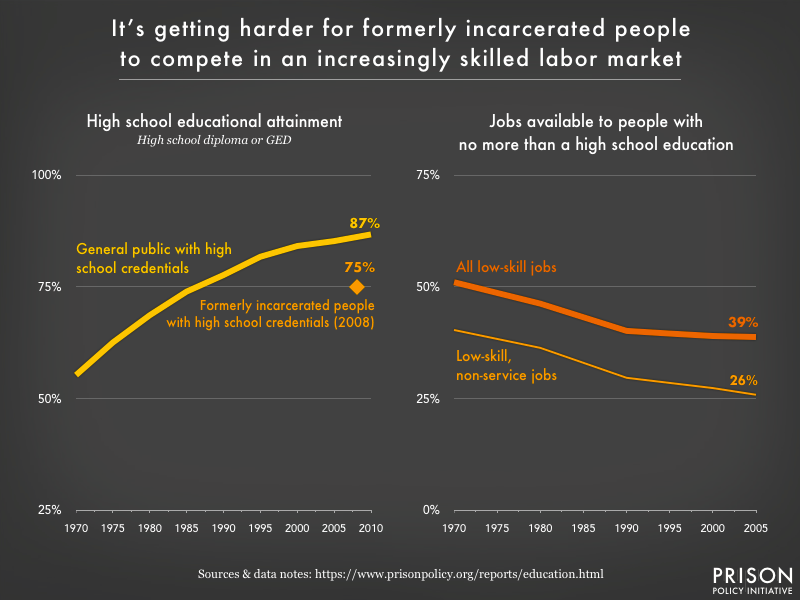

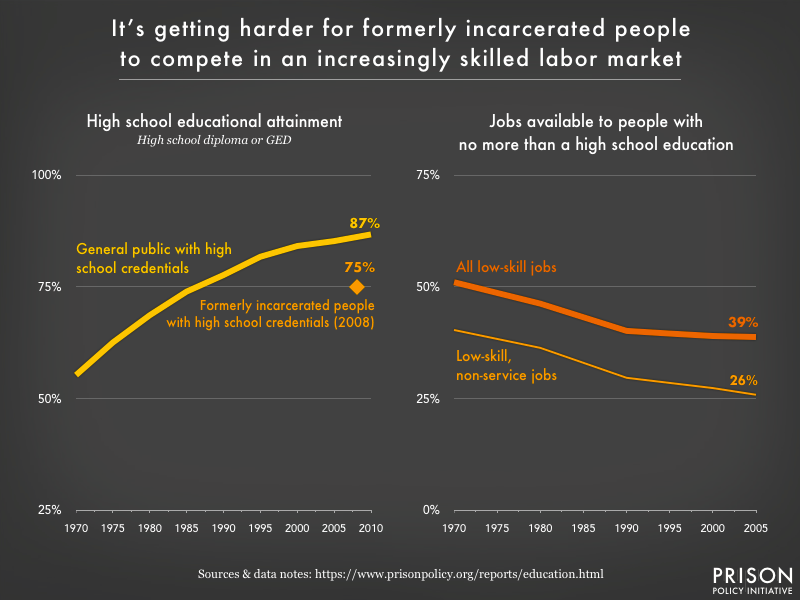

9. Explaining the links between education, the labor market, and unemployment among formerly incarcerated people

We connected the dots to show that changes in the labor market, combined with lagging educational attainment, have made it harder for formerly incarcerated people to compete for a dwindling number of low-skill jobs. This graphic from Getting Back on Course helps explain why unemployment rates are so high & and the need for educational opportunities is so great & for formerly incarcerated people:

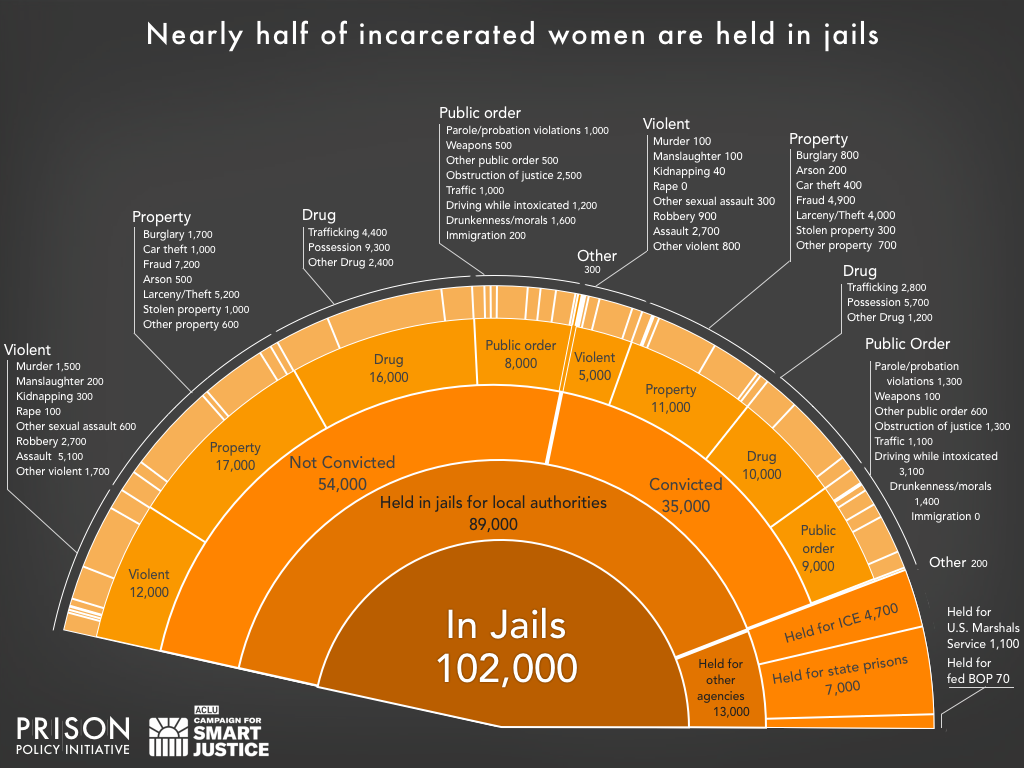

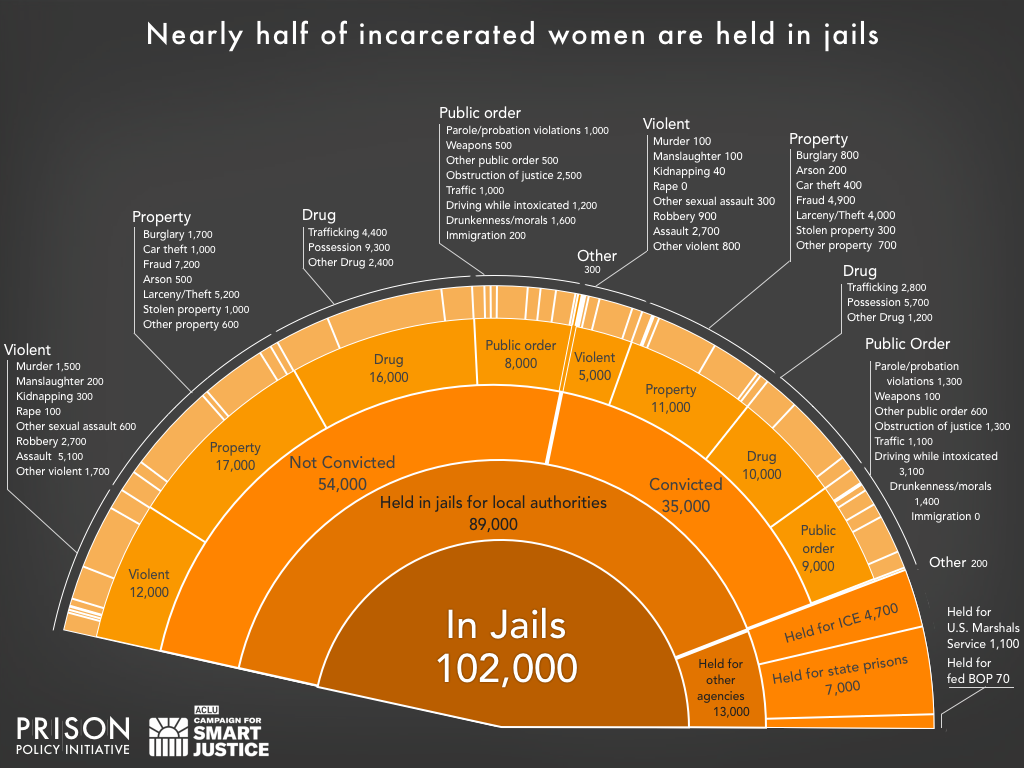

10. The “Whole Pie” for women’s incarceration

This year, we went deeper with our analysis of women’s incarceration in our update to Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, produced in collaboration with the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice. Women remain an overlooked segment of the incarcerated population, despite the rapid growth of women’s prison and jail populations. This report offers a snapshot of how many women are locked up on a given day, where, and why. A new detailed view of the 102,000 women held in local jails reveals that over half are unconvicted and awaiting trial:

While we continue to be frustrated by the lack of gender-specific data reported by government agencies, this report compiles the best sources available to help ensure that women are not left behind in the effort to end mass incarceration.

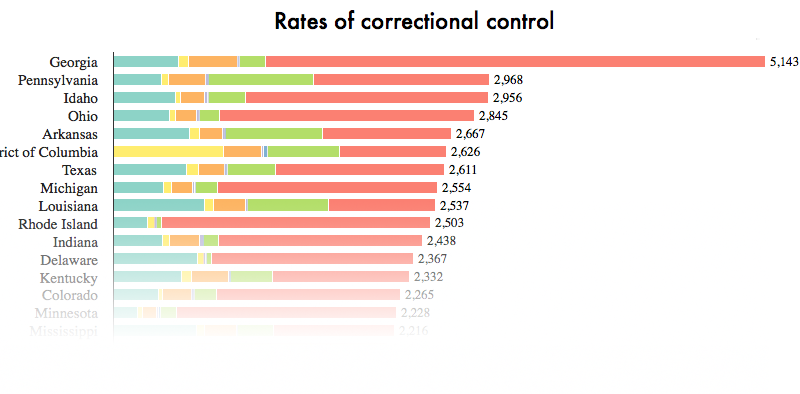

11. The big picture: correctional control by state

In our final report and infographic of the year, we compiled all of the state-level data available on various forms of state control — including incarceration in prisons and jails, probation, parole, youth confinement, involuntary commitment, and Indian Country jails — to give a more complete picture of correctional control. This broader view reveals that some states with comparatively low incarceration rates (like Rhode Island and Minnesota) have some of the highest rates of community supervision. Again, we are reminded that to end mass incarceration, every state will need to rethink its use of correctional control.

Our picks for writing that propels reform by offering a more complete understanding of mass incarceration.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

December 27, 2018

This year, attorneys, researchers, and advocates proposed a more complete understanding of mass incarceration as a way to hasten its undoing. Here are our picks:

- My Resolution for 2018: Less Piety, More Complexity

Joseph Margulies

Justia Verdict

January 8, 2018

According to attorney and law professor Joseph Margulies, supporters of criminal justice reform resort to a few go-to critiques of the criminal justice system that can be summed up with, “What led to the punitive turn in criminal justice? Conservative whites wanted a new way to control blacks. How did we get mass incarceration? The war on drugs. And what is the war on drugs? Yet another way for whites to destroy the lives of young black men.” In this column, Margulies explains how these narratives oversimplify the issue of mass incarceration and announces that he is discarding easy but incomplete explanations.

- How a Bad Law and a Big Mistake Drove My Mentally Ill Son Away

Norman J. Ornstein

The New York Times

March 6, 2018

Sharing his personal story of using Florida’s Baker Act to involuntarily commit his son, Norman J. Ornstein is rightfully skeptical that three-day mental health holds can prevent tragedies like suicide and murder. Instead, Ornstein calls for comprehensive mental health treatment, respect for people with mental illness’ civil liberties, and empowering their family members.

- The Recidivism Trap

Jeffrey A. Butts and Vincent Schiraldi

The Marshall Project

March 14, 2018

In this op-ed, researchers Jeffrey A. Butts and Vincent Schiraldi propose a new approach to evaluating criminal justice systems that no longer focuses on recidivism but rather asks whether interventions are helping formerly convicted people become more law-abiding. Under this new approach, for example, a person who was arrested five times for burglary in one year but only once the following year would be viewed as someone who has taken a step away from crime. Butts and Schiraldi are hopeful that changing the measure of success would result in solutions that more effectively fulfill the goals of corrections and rehabilitation.

- Black crime victims too frequently slighted by justice system

Tanya Coke

USA Today

April 18, 2018

Tanya Coke, a former criminal defense attorney and crime survivor, describes the barriers that prevent black crime survivors from getting the healing they need. Too often, black males are assumed to be perpetrators of violence rather than victims. As a result, racial bias infects prosecutions, crime reporting, and service delivery. For example, access to crime victims compensation funds requires a police report, which victims of color may feel too distrustful of police to acquire. The op-ed is hopeful, highlighting the work of organizations such as Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice, which are providing a platform for crime survivors of color to influence criminal justice reform.

- What Nelson Mandela Lost

Tayari Jones

The New York Times

July 6, 2018

English professor Tayari Jones uses the publication of Nelson Mandela’s letters from prison to highlight the impact of imprisonment. Incarcerated people are “subjected to great violence, as though their sentence invalidates their own legal protections. While these severe deprivations are harrowing, Mr. Mandela’s prison letters underscore isolation’s other violence: Every incarcerated human is stripped of family.” Jones proposes that to properly honor Nelson Mandela, we should remember him as not only an international leader, but also one of the many incarcerated men and women separated from their families and denied basic rights.

- 3 Years Later, The Federal Government Still Hasn’t Counted Sandra Bland’s Death

Ryan J. Reilly

Huffington Post

July 13, 2018

The Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics has been counting jail deaths since 2000, releasing the data annually. But the office hasn’t done so since December 2016, when it reported data from 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics officials told the Huffington Post that the 2015 data would be out this month, but researchers and advocates are still waiting. The data is crucial where suicides are consistently the leading cause of death in jail and the rate of jail suicides far surpasses that of state prisons or the American population in general. The incidence of jail deaths can alert authorities and policymakers to systemic issues such as lax oversight. The data is a necessary first step to ensuring that detention is not a matter of life and death.

- When the Police Become Prosecutors

Alexandra Natapoff

The New York Times

December 26, 2018

In an op-ed for The New York Times, law professor Alexandra Natapoff both shines light on the need to include misdemeanors in calls for criminal justice reform and reveals that, in some states, police officers act as prosecutors. Natapoff reminds readers that even minor criminal charges can have disastrous consequences. People may be detained pretrial and as a result lose their jobs, disrupt their child care, or risk their immigration status. They may struggle with paying fines, completing probation, or obtaining future employment, education, and housing. Further, in hundreds of misdemeanor courts in at least 14 states, defendants face a peculiar setup. Police officers can file criminal charges and handle court cases, meaning people must defend themselves against and negotiate with the very people who arrested them.

Reporters are deepening our understanding of complex facets of the criminal justice system and illuminating paths to reform. We share some of our favorites.

by Bernadette Rabuy,

December 27, 2018

This year, reporters gave a voice to the vulnerable, filled in critical data gaps, and deepened our understanding of complex issues in the criminal justice system. Here are some of our favorites:

- One War. Two Races.

Herald-Tribune

December 2017*

Analyzing millions of records across five databases, this four-part series published late last year finds that drug laws continue to disproportionately hurt Black defendants in Florida, even as the drug epidemic extends its reach beyond communities of color and treatment becomes more common. The series includes an interactive map that allows readers to grasp how each region is confronting the drug epidemic. A review of one state prosecutor’s drug cases revealed that he was far more likely to drop charges against white defendants than Black defendants. In Highlands County, judges sentence Blacks to more than double the time than whites for felony drug crimes. Even when it comes to drug court or government-funded treatment programs, Blacks are less likely to have the opportunity to participate. The Herald-Tribune’s series highlights that despite shifts in the response to substance abuse, racial bias stubbornly remains.

- How to Buy a Gun in 15 Countries

Audrey Carlsen and Sahil Chinoy

The New York Times

March 2, 2018

The ease with which many Americans purchase guns is unique internationally. This piece lays out the process for buying guns in fifteen countries, demonstrating that the U.S. is out of step with many other countries in not requiring firearm safety training, police inspections of storage, or interviews of potential buyers’ family, friends, and neighbors. The article suggests that gun ownership in the U.S. surpasses that of any other country because of the country’s lax requirements for ownership.

- Women describe degrading strip searches at Baker prison visitation

Ben Conarck

The Florida Times-Union

March 21, 2018

Earlier this year, the Florida Department of Corrections enacted a policy requiring that visitors undergo strip searches if they set off metal detectors. Ben Conarck investigates whether there is support for the department’s purported justification that visitors are bringing in contraband. Conarck finds that corrections officers, prison researchers, and even the department’s own data agree that contraband rarely enters prisons through visitors. Be sure to also check out The Florida Times-Union’s editorial arguing that there is no justifiable reason for Florida to discourage visitation and our own national survey of contraband in jails, which calls into question visitation policies that criminalize incarcerated people’s loved ones.

- Prosecutors aren’t just enforcing the law—they’re making it

Josie Duffy Rice

The Appeal

April 20, 2018

These days, it seems like everybody is talking about the powerful role that prosecutors hold in the criminal justice system. In this article, Josie Duffy Rice shines light on their less talked-about but influential reach as lobbyists. Trading on paranoia and fear, district attorneys nationwide not only enforce the law but also make it. Prosecutors adamantly oppose legislative reforms that promote mercy toward defendants or implement oversight over law enforcement.

- Sex Crimes and Criminal Justice

Barbara Koepple

The Washington Spectator

May 4, 2018

Barbara Koepple allows readers to peek behind the curtain of civil commitment, the practice of states civilly detaining people convicted of sexual offenses after completion of their prison sentences. While states claim that civil commitment is necessary to prevent sexual crimes, Koepple explains that its roots actually trace back to ill-founded beliefs about how likely people convicted of sexual offenses are to recidivate and disproportionate media reporting of sexual crimes. The investigation uncovers a broken system, in which it is nearly impossible for people to be released from civil commitment, whether due to the subjectivity of the criteria for release or irrational rules that can easily be broken. In pointing out the high costs of civil commitment and other approaches in states like Vermont and internationally, the article is also an urgent call for reform.

- Mothers Are Incarcerated at Record Rates, Yet Prison-Nursery Beds Go Empty

Victoria Law

Jezebel

May 13, 2018

Despite the thousands of pregnant women behind bars each year and the upward trend in women incarcerated, Victoria Law finds that most correctional nursery programs have empty beds. Correctional nursery programs have real benefits such as making it less likely that an incarcerated mother will lose her parental rights, but the stringent eligibility criteria make it difficult to participate even when a program is available. Prison nurseries highlight broader challenges in the movement for criminal justice reform— prioritizing community alternatives to incarceration and making reforms available to people convicted of violent offenses.

- Trump’s catch-and-detain policy snares many who have long called U.S. home

Mica Rosenberg and Reade Levinson

Reuters Investigates

June 20, 2018

When the media and the public were focused on Trump’s family separation policy, Mica Rosenberg and Reade Levinson highlighted an unofficial family separation policy. Under Trump, ICE denies bond much more frequently, requiring even immigrants with little to no criminal history and deep roots in their communities to wait for their hearings behind bars. The investigation explains how local police collaborate with ICE by turning over immigrants suspected of committing minor traffic violations and provides an additional example of the tenuous link between pretrial detention and public safety.

- If He Didn’t Kill Anyone, Why Is It Murder?

Abbie VanSickle

The New York Times

June 27, 2018

Abbie VanSickle shines light on the California legislature’s efforts to scale back felony murder, a legal doctrine which allows individuals involved in certain kinds of serious felonies that lead in death to be held as liable as the killer. One motivation for reform was felony murder’s disproportionate impact on women and young Black and Latino men. The legislation, which the governor successfully signed into law, changes state law so that only someone who actually killed, intended to kill, or acted as a major player can be charged with murder. The article highlights that the distinction between violent and nonviolent offenses can be murky.

- Police Violence Map

Mapping Police Violence

2018

Mapping Police Violence compiles data from three databases, FatalEncounters.org, the U.S. Police Shootings Database, and KilledbyPolice.net, and their own sifting through social media and obituaries to find that police have killed 1,122 people in 2018. The interactive map memorializes the victims and provides a description of the incident, information about whether the officer was charged, and links to related news stories. The Police Violence Map provides critical data that the government has thus far failed to systematically report.

*Technically 2017, but we thought it was worth including this in-depth undertaking that we initially missed

The fight to make prison and jail phone calls affordable began in 2000. For those wondering "why is this taking so long?", here are the key dates.

by Peter Wagner and Alexi Jones,

December 17, 2018

Journalists and others often ask about how the movement for phone justice began and why this is taking so long. Here are the key dates:

- 2000:

- Martha Wright, a grandmother who was struggling to afford calls to her incarcerated grandson, sues a private prison company over the contracts it has with various phone companies.

- 2001:

- Federal Court grants motions by private prison company and telephone companies to refer the case to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

- 2002-2011:

- For nearly 10 years, the Federal Communications Commission takes no visible action.

- 2012:

- The Federal Communications Commission files a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) regarding the Wright Petition.

- 2013:

- The Federal Communications Commission votes 2-1 to approve new regulations that set interstate rate caps of 21 cents a minute for debit and pre-paid calls and 25 cents a minute for collect calls. The one dissenting vote is from FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai, who previously represented prison phone giant Securus in private practice.

- 2014:

- Despite legal challenges from prison phone companies, the FCC’s new rate caps go into effect in February.

- 2015:

- In October, the FCC issues additional regulations, lowering the cost for all calls from prisons (out-of-state and in-state) to 11 cents a minute, and lowering the cost of calls from jails at 14 to 22 cents a minute depending on the size of the institution. The FCC also approves comprehensive reform and caps on the cost of “ancillary fees” that can double the cost of a call. Again, Commissioner Pai voted against these regulations. Many of the phone companies, several state prison systems, county jail systems, and sheriff associations file suit challenging the FCC’s order.

- 2016:

- The federal court issues a partial stay of the Federal Communications Commission’s October 2015 regulations, preventing the new rate caps from taking effect. The new regulations on fees, however, go into effect. The lawsuit moves very slowly.

- 2017:

- In January, Donald Trump appoints FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai the Chairman of the FCC. In February, Pai, who had twice voted against regulating the industry, announces that the FCC will stop defending its in-state rate caps in court. However, the FCC does consent to 6 advocacy organizations, including the Prison Policy Initiative, defending that part of the lawsuit as intervenor-defendants. In June, despite this effort, the federal court strikes down the FCC’s 2015 rate caps. The 2013 rate caps, and the 2015 fee caps, remain in place.

For more on the struggle for phone justice, see our campaign page.

by Aleks Kajstura,

December 12, 2018

This report has been updated with a new version for 2022.

The 2019 legislative session is almost upon us, and we’ve compiled – as we do every year – a list of under-discussed but winnable criminal justice reforms. While federal prison reform continues to receive more than its fair share of attention, state legislatures and governors remain empowered to determine the future of mass incarceration.

The 2019 legislative session is almost upon us, and we’ve compiled – as we do every year – a list of under-discussed but winnable criminal justice reforms. While federal prison reform continues to receive more than its fair share of attention, state legislatures and governors remain empowered to determine the future of mass incarceration.

We publish this list as a briefing with links to more information and model bills, and recently sent it to reform-minded state legislators across the country. (To read about recent legislative victories on these fronts – such as three states ending unnecessary driver’s license suspensions in 2018! – see our new Annual Report.)

Our list of reforms ripe for legislative victory are:

- Ending prison gerrymandering

- Lowering the cost of calls home from prison or jail

- Protecting in-person family visits from the video calling industry

- Stopping automatic driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving

- Repealing or reforming ineffective and harmful sentencing enhancement zones

- Protecting letters from home in local jails

- Requiring racial impact statements for criminal justice bills

- Creating a “safety valve” for mandatory minimum sentences

- Eliminating “pay only” probation and regulating privatized probation services

- Reducing pretrial detention

- Decreasing state incarceration rates by reducing jail populations

- Curbing the exploitation of people released from custody

- Ending electronic monitoring for individuals on parole

- Shortening excessive prison sentences

Could your state be working on any of these reforms? We’re looking forward to the progress we can make together in 2019!

December 11, 2018

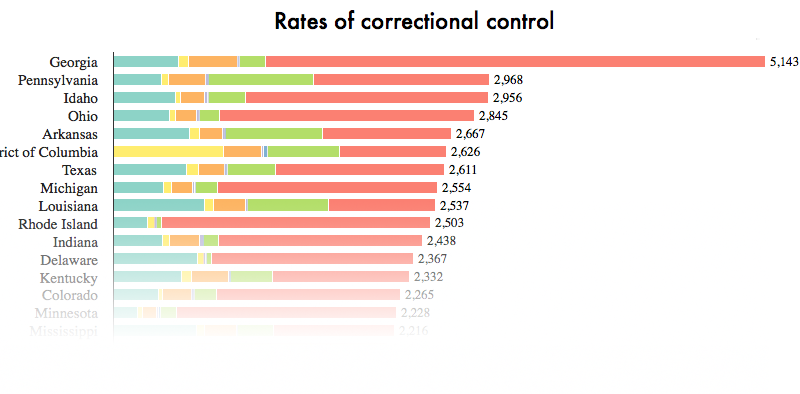

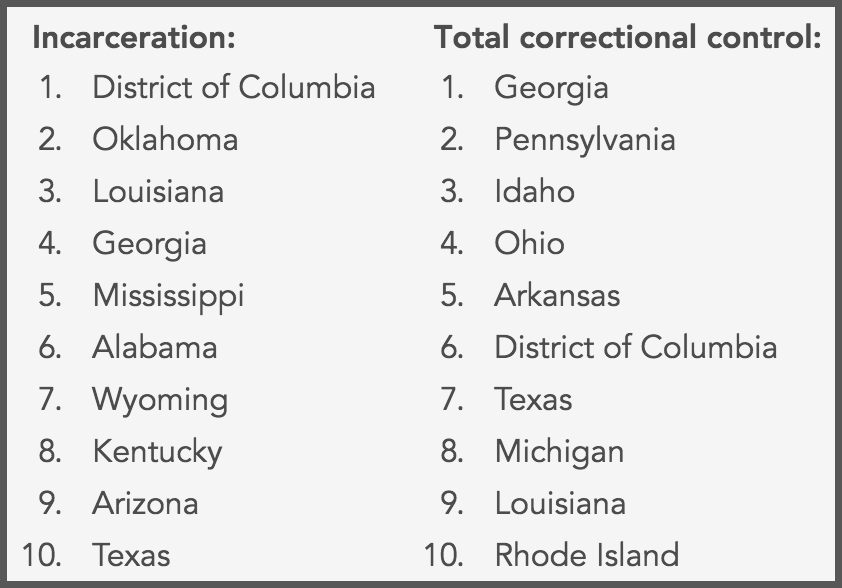

When it comes to ranking U.S. states on the harshness of their criminal justice systems, incarceration rates only tell half of the story. 4.5 million people nationwide are on probation and parole, and several of the seemingly “less punitive” states put vast numbers of their residents under these other, deeply flawed forms of supervision.

In Correctional Control: Incarceration and supervision by state, the Prison Policy Initiative calculates each state’s rate of correctional control, which includes incarceration (in all types of facilities) as well as community supervision (probation and parole). The report includes over 100 easy-to-read charts breaking down each state’s correctional population.

The report also includes an interactive chart that ranks states on their use of correctional control, with surprising findings including:

- Ohio and Idaho surpass Oklahoma – the global leader in incarceration – in correctional control overall.

- Pennsylvania – which famously revoked Meek Mill’s probation last year – has the second-highest rate of correctional control in the nation.

- Rhode Island and Minnesota have some of the lowest incarceration rates in the country, but are among the most punitive when community supervision is accounted for.

Many of the highest rates of correctional control are in states with high rates of probation. “All too often,” says report author Alexi Jones, “probation serves not as a true alternative to incarceration but as the last stop before prison.” Jones proposes specific reforms and highlights the flaws in current probation systems:

- Probation imposes time-consuming conditions and fees that people struggle to meet, and which can paradoxically hold them back from turning their lives around.

- Violating even the most minor of these requirements (such as missing a meeting) can result in incarceration.

- Probation terms can go on for years after the original offense, meaning even model probationers can serve decades under state scrutiny.

But probation is malfunctioning in even more fundamental ways, explains Jones: “States are putting people on probation when a fine, warning, or community treatment program would suffice,” thereby putting more people at risk of incarceration.

“It’s obviously better to keep people in the community than to incarcerate them,” says Jones. “But states need to ask the hard questions about their supervision systems: Whether probation and parole are truly helping people get their lives back on track, and whether everyone who is under supervision really needs to be.”

Treatment programs offer promising results for recently incarcerated people, but prisons aren’t using them.

by Maddy Troilo,

December 7, 2018

The national opioid epidemic is killing formerly incarcerated people at shocking rates. Recent research from North Carolina, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island reveals the extent of this crisis and points towards possible solutions. Despite a growing body of evidence that specific treatments work effectively, most prisons are refusing to offer those treatments to incarcerated people, vastly worsening the overdose rate among people in and recently released from prison. Last month, the President signed into law the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, which aims to combat the national epidemic but will likely have mixed results. States, departments of corrections, and the federal government can and must do more to help.

Continue reading →

When jails cut family visits in the name of security, advocates should demand evidence.

by Jorge Renaud,

December 6, 2018

Sheriffs are increasingly welcoming video calling technology into their jails, with more than 500 local jails now contracting with video calling providers like GTL and Securus. Usually, sheriffs simultaneously do away with in-person visits, despite studies showing that they are crucial for maintaining family bonds.

To ward off claims that this is just a money-grubbing scheme, sheriffs invoke the argument that doing away with face-to-face visits “increase[s] the safety and security of our facilities,” presumably by stopping contraband brought in by jail visitors.

This argument is demonstrably false, and yet jail administrators repeat it at every possible opportunity. Sheriffs raise the specter of visitors loaded down with drugs, somehow passing them through physical searches and through body scanners and through glass partitions, with the only solution being a move to remote technology. For one thing, this scenario is implausible, given that in-person jail visitors are virtually always separated from their loved ones by a glass window. But more importantly, by blaming contraband on in-person visitors, sheriffs distract from a far more likely source: jail staff.

I reviewed news stories of arrests made in 2018 of individuals caught bringing contraband into jails and prisons. What I found wouldn’t surprise any person in jail, but it’s a truth that sheriffs prefer to avoid: Almost all contraband introduced to any local jail comes through staff. This year alone, 20 jail staff members in 12 separate county jails were arrested, indicted, or convicted on charges of bringing in or planning to bring in contraband.

| State |

Facility |

Details of incident |

| Alabama |

Marshall County Jail |

Sheriff fires, arrests, and charges four jail staff for “promoting prison contraband.” (more) |

| Florida |

Lake County Correctional Center |

Jail staff charged with smuggling marijuana and phone. (more) |

| Maryland |

Jessup Correctional Institution |

Two staff indicted for conspiring to bring in drugs. (more) |

| Mississippi |

Bolivar County Regional Correctional Facility |

Jail staff arrested for smuggling contraband. (more) |

| Missouri |

Jackson County Detention Center |

Jail staff sentenced for bringing in contraband phones, cigarettes, and drugs. (more) |

| Ohio |

Lucas County Correctional Center |

Two staff indicted for conspiring to bring in drugs. (more) |

| Pennsylvania |

Lebanon County Correctional Facility |

Jail staff arrested for smuggling meth, suboxone, and naloxone. (more) |

| Pennsylvania |

Philadelphia House of Corrections, Detention Center, and Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility |

Six staff at four Philadelphia facilities arrested for smuggling drugs and phones into jail. (more) |

| Texas |

Bexar County Jail |

Two staff indicted for conspiring to smuggle meth into jail. (more) |

In fact, most of the jails in question had recently eliminated in-person visits in favor of video calls – a technology which, again, is supposed to reduce contraband.

Moving to video calling has financial benefits for jails, and those benefits have convinced sheriffs to overlook the importance of in-person visits for incarcerated individuals and their families. While rates charged for video calls vary, almost every jail that offers video calling receives commissions from the provider. Video calling also reduces the number of jailers necessary to monitor visitation, allowing sheriffs to cut their payroll.

In order to realize those financial benefits, sheriffs have to justify taking away children’s right to see their parents in person. And that means blaming families for contraband, even when that claim has no legs to stand on.

If any sheriff has ever commissioned a study to back up their claim that banning in-person visits makes jails safer, they’ve never cited one. However, multiple studies (including one we assisted with) do suggest that banning in-person visits makes jails less safe overall, with no reduction in contraband.

Advocates for in-person visits should demand that sheriffs provide proof of their claims. Banning in-person visits means more money for jails at the expense of family connections. We can’t let the sheriffs’ baseless assertions to the contrary go unchallenged.

We've had an incredibly productive year. In our new annual report, we share the highlights.

by Peter Wagner,

November 29, 2018

We just released our 2017-2018 Annual Report, and I’m thrilled to share some highlights of our work with you. We’ve had an incredibly productive year, releasing 11 major national reports, exposés, legislative briefings, and guides for advocates and journalists.

There are a few successes I’m particularly proud of:

But that’s not all. In our highly-skimmable annual report, we review our work on all of our issues over the last year. Thank you for being a part of our successes over the last year. We are looking forward to working with you in the year to come.

by Peter Wagner,

November 21, 2018

Mujahid Farid, the founding organizer of a campaign to reduce the number of elderly and infirm people in New York State prisons, died yesterday at 69. His Release Aging People in Prison campaign in New York State – known as the RAPP Campaign – was critical:

Release Aging People in Prison/RAPP works to end mass incarceration and promote racial justice by getting elderly and infirm people out of prison. The number of people aged 50 and older in New York State, where RAPP was founded, has doubled since 2000; it now exceeds 10,000—about 20% of the total incarcerated population. This reflects a national crisis in the prison system and the extension of a culture of revenge and punishment into all areas of our society.

I got to spend some time with Farid at a conference in 2014, and offered to use our knowledge of the New York State prison system’s data to help visualize what Farid already knew: that New York’s much-heralded prison population decline was confined solely to the population of people under 50 and the elderly were being left behind. We’ve updated that graph and analysis a few times, most recently just three weeks ago:

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

And at that same conference in 2014, Leah Sakala and I shot a short interview with Farid when the RAPP Campaign was just starting:

Each summer since, I’d see Farid at that same conference, and checking in with him was always a highlight. He’ll be greatly missed. Thank you for your work, Mujahid Farid.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.