Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2018

By Peter Wagner and Wendy Sawyer

March 14, 2018

Press release

This report is old. See our new version.

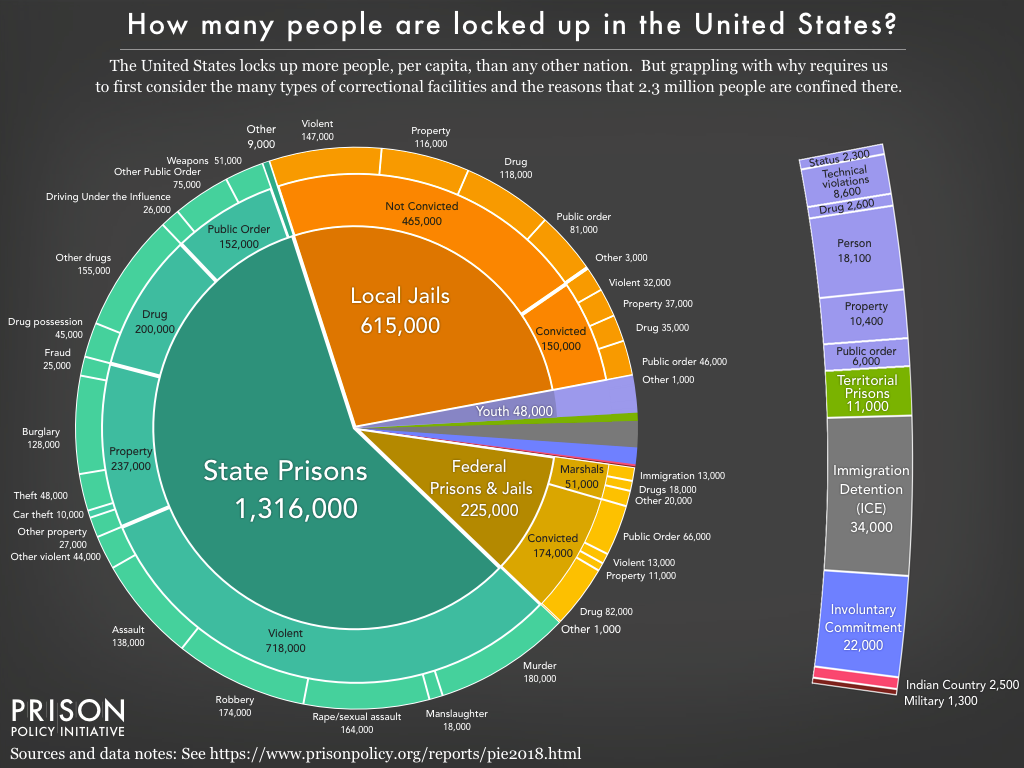

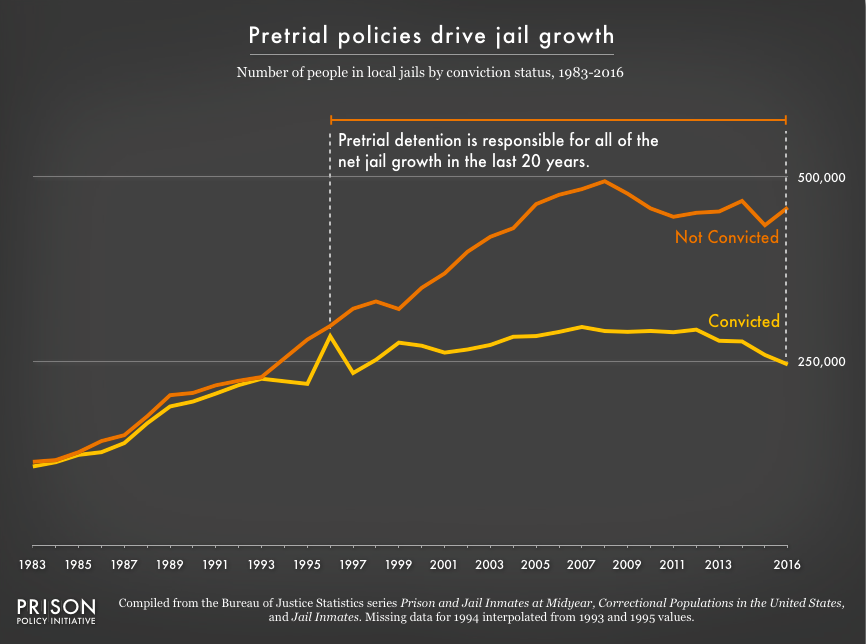

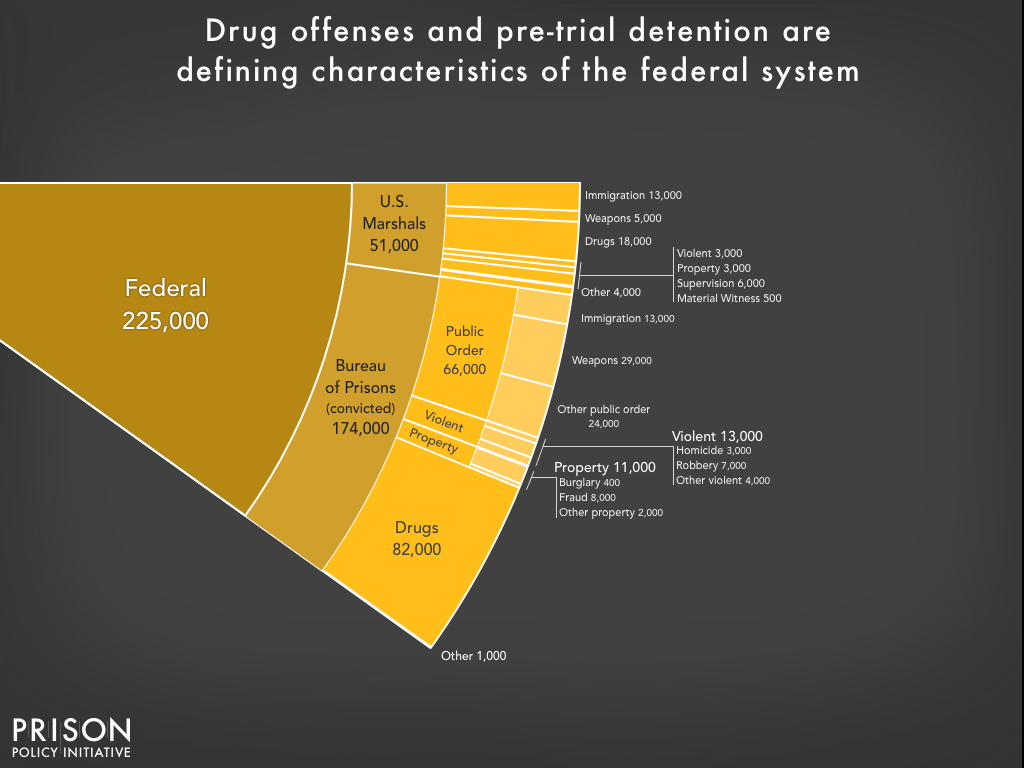

Can it really be true that most people in jail are being held before trial? And how much of mass incarceration is a result of the war on drugs? These questions are harder to answer than you might think, because our country’s systems of confinement are so fragmented. The various government agencies involved in the justice system collect a lot of critical data, but it is not designed to help policymakers or the public understand what’s going on. Meaningful criminal justice reform that reduces the massive scale of incarceration, however, requires that we start with the big picture.

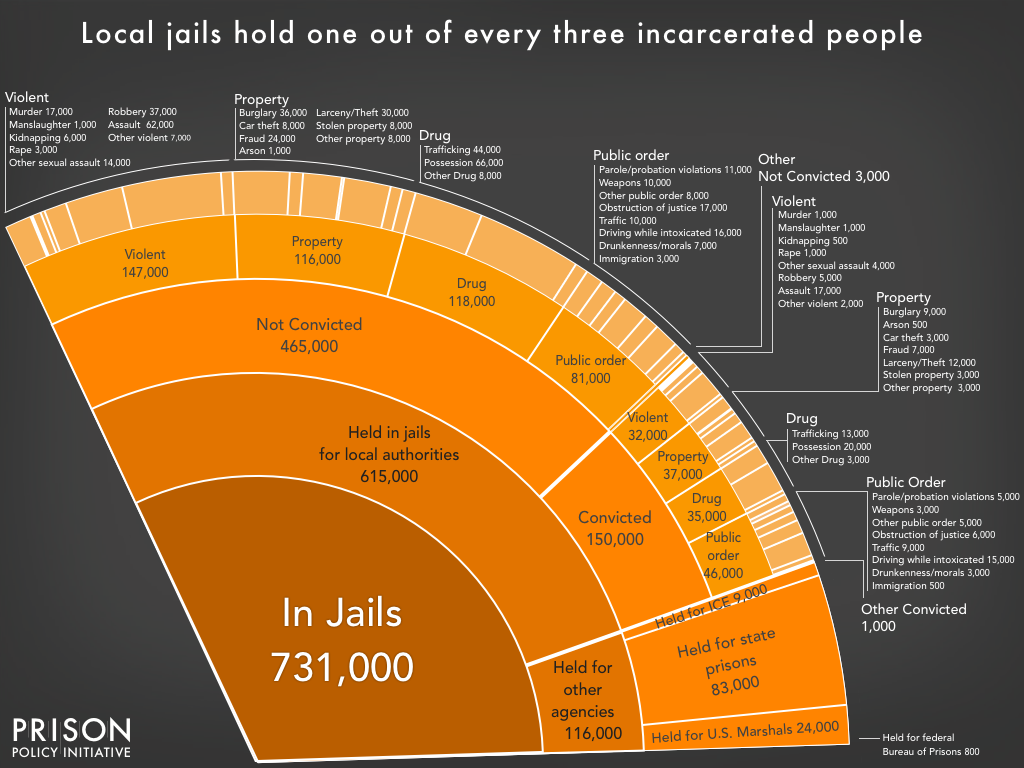

This report offers some much needed clarity by piecing together this country’s disparate systems of confinement. The American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 1,852 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails, and 80 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.1 And we go deeper to provide further detail on why people are locked up in all of those different types of facilities.

Slideshow 1. Swipe for more detailed views.

This report is old. See our new version.

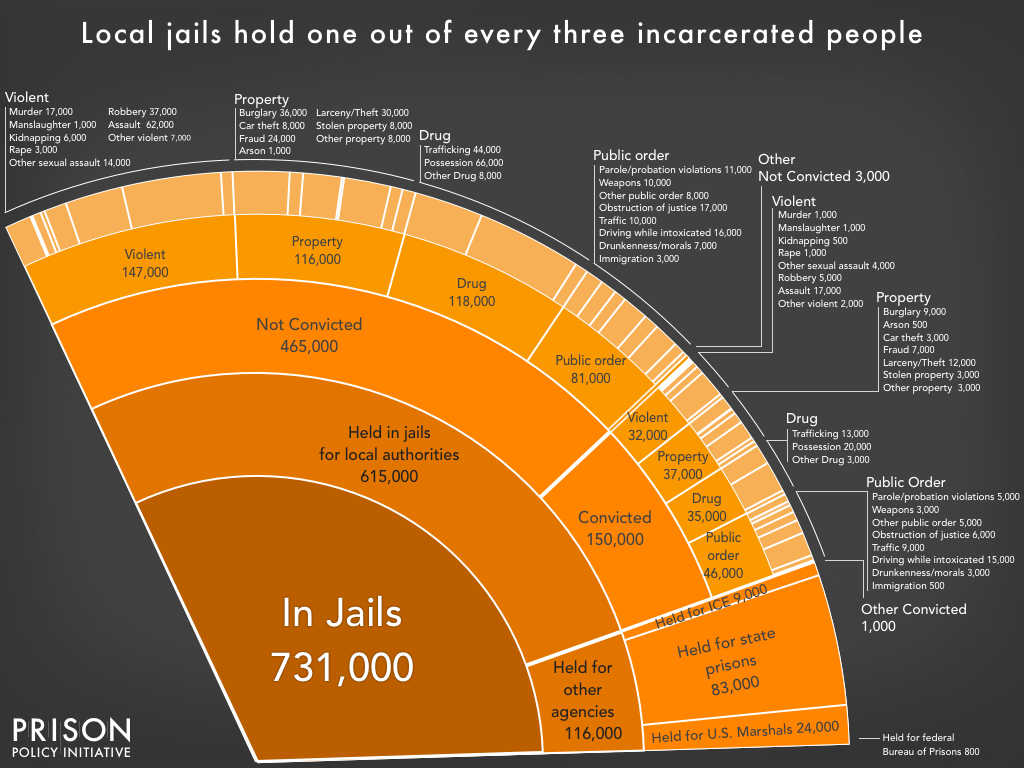

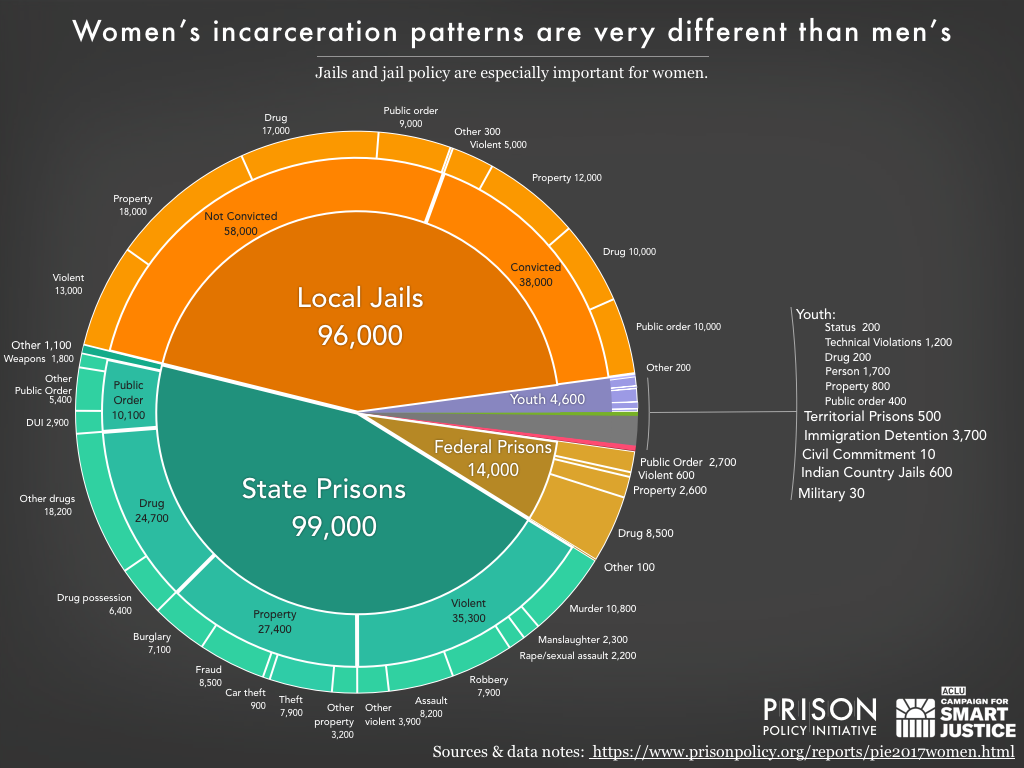

This big-picture view allows us to focus on the most important drivers of mass incarceration and identify important, but often ignored, systems of confinement. The detailed views bring these overlooked parts of the “pie” to light, from immigration detention to civil commitment and youth confinement. In particular, local jails often receive short shrift in larger discussions about criminal justice, but they play a critical role as “incarceration’s front door” and have a far greater impact than the daily number suggests.

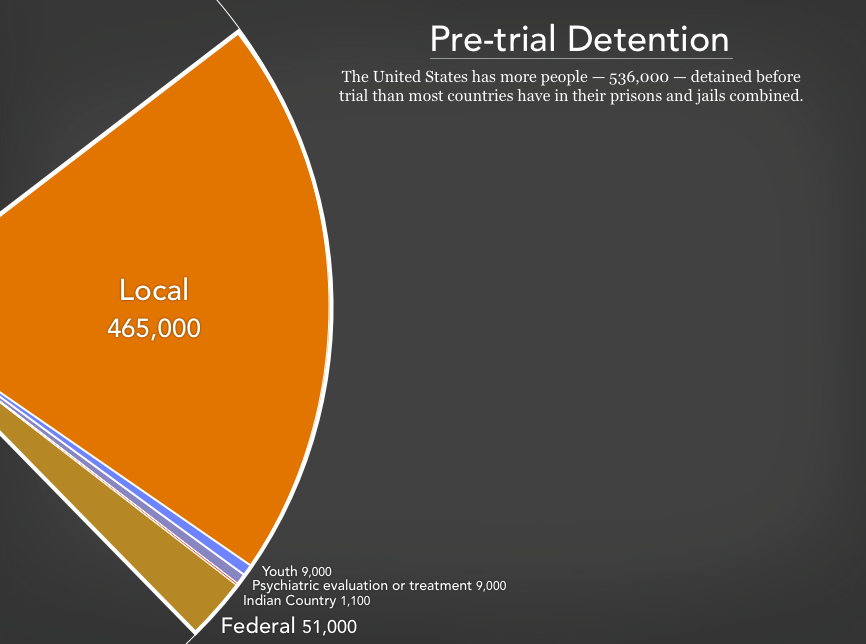

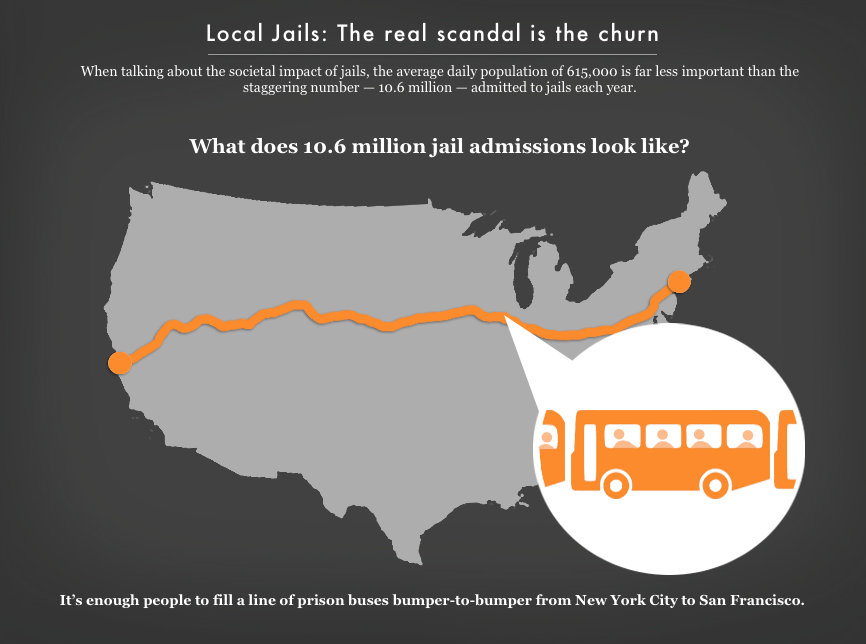

While this pie chart provides a comprehensive snapshot of our correctional system, the graphic does not capture the enormous churn in and out of our correctional facilities and the far larger universe of people whose lives are affected by the criminal justice system. Every year, 626,000 people walk out of prison gates, but people go to jail 10.6 million times each year.2 Jail churn is particularly high because most people in jails3 have not been convicted. Some have just been arrested and will make bail in the next few hours or days, and others are too poor to make bail and must remain behind bars until their trial. Only a small number (150,000 on any given day) have been convicted, generally serving misdemeanors sentences under a year.

Slideshow 2. Swipe for more detail on pre-trial detention.

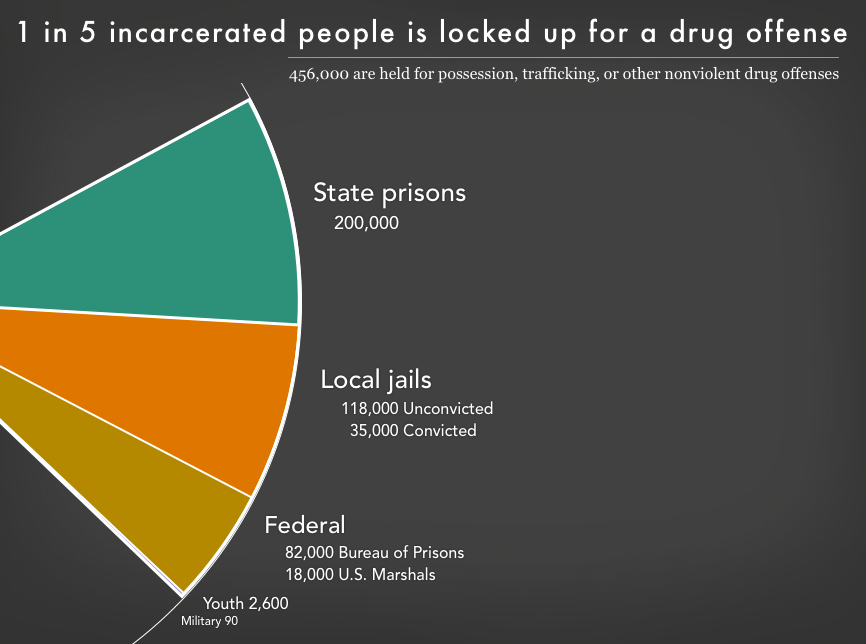

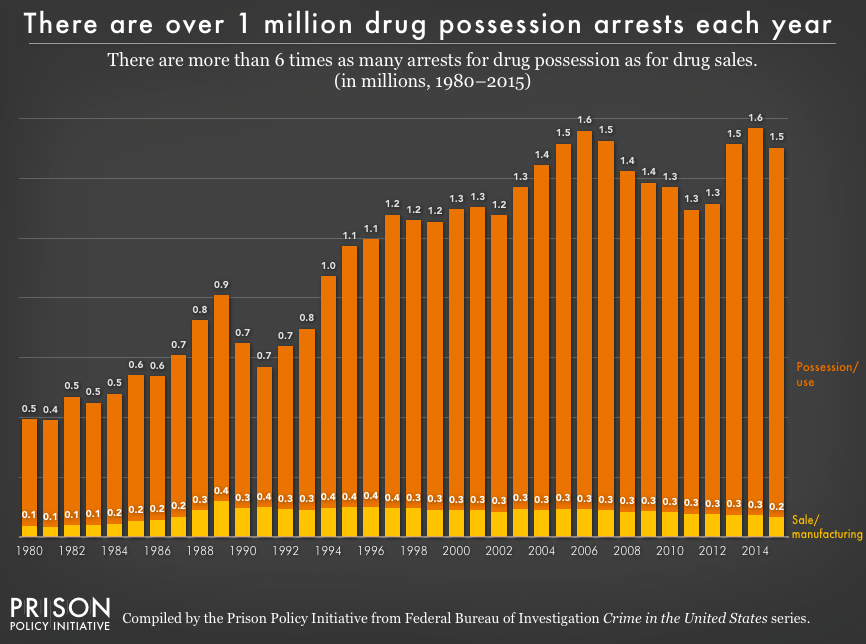

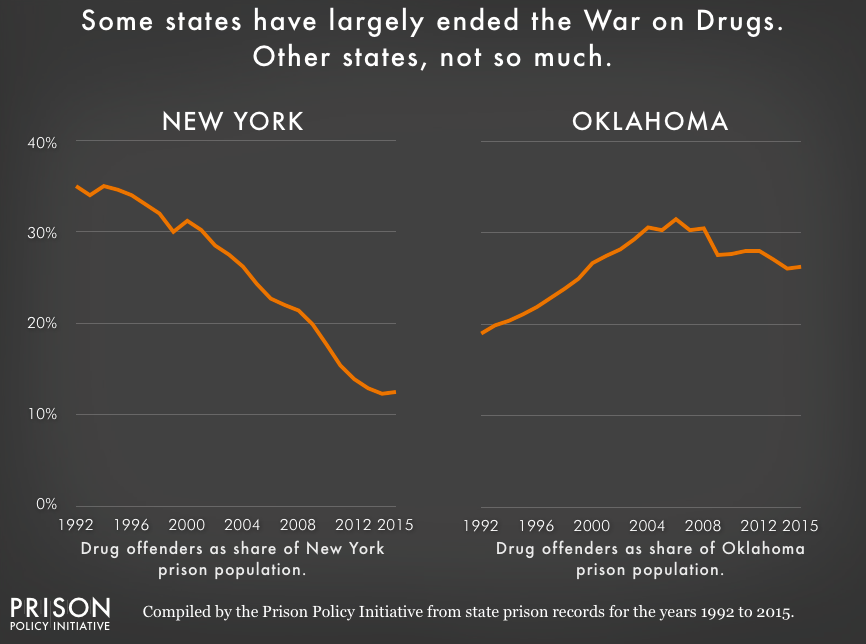

With a sense of the big picture, a common follow-up question might be: how many people are locked up for a drug offense? We know that almost half a million people are locked up because of a drug offense.4 The data confirms that nonviolent drug convictions are a defining characteristic of the federal prison system, but play only a supporting role at the state and local levels. While most people in state and local facilities are not locked up for drug offenses, most states’ continued practice of arresting people for drug possession5 destabilizes individual lives and communities. Drug arrests give residents of over-policed communities criminal records, which then reduce employment prospects and increase the likelihood of longer sentences for any future offenses.

Slideshow 3. Swipe for more detail on the War on Drugs.

Offense categories don’t tell the whole story

The criminal justice system involves some complicated decisions and relationships, some — but not all — of which can be represented graphically. For example, it’s easy to show how jails rent space to state and federal agencies, and that 5,000 youth are actually in adult facilities.6 But the offense data oversimplifies how people interact with the criminal justice system. A person in prison for multiple offenses is reported only for the most serious offense7 so, for example, there are people in prison for “violent” offenses who might have also been convicted of a drug offense. Further, almost all convictions are the result of plea bargains, where people plead guilty to a lesser offense, perhaps of a different category or one that they may not have actually committed.

And many of these categories group together people convicted of a wide range of offenses. For example, “murder” is generally considered to be an extremely serious offense, but “murder” groups together the rare group of serial killers with people who committed acts that are unlikely for reasons of circumstance or advanced age to ever happen again. It also includes offenses that the average American may not consider to be murder at all. For example, the felony murder rule says that if someone dies during the commission of a felony, everyone involved can be as guilty of murder as the person who pulled the trigger. Driving a getaway car during a bank robbery where someone was accidentally killed is indeed a serious offense, but many may be surprised that this is considered murder.8

Lessons from the smaller “slices”

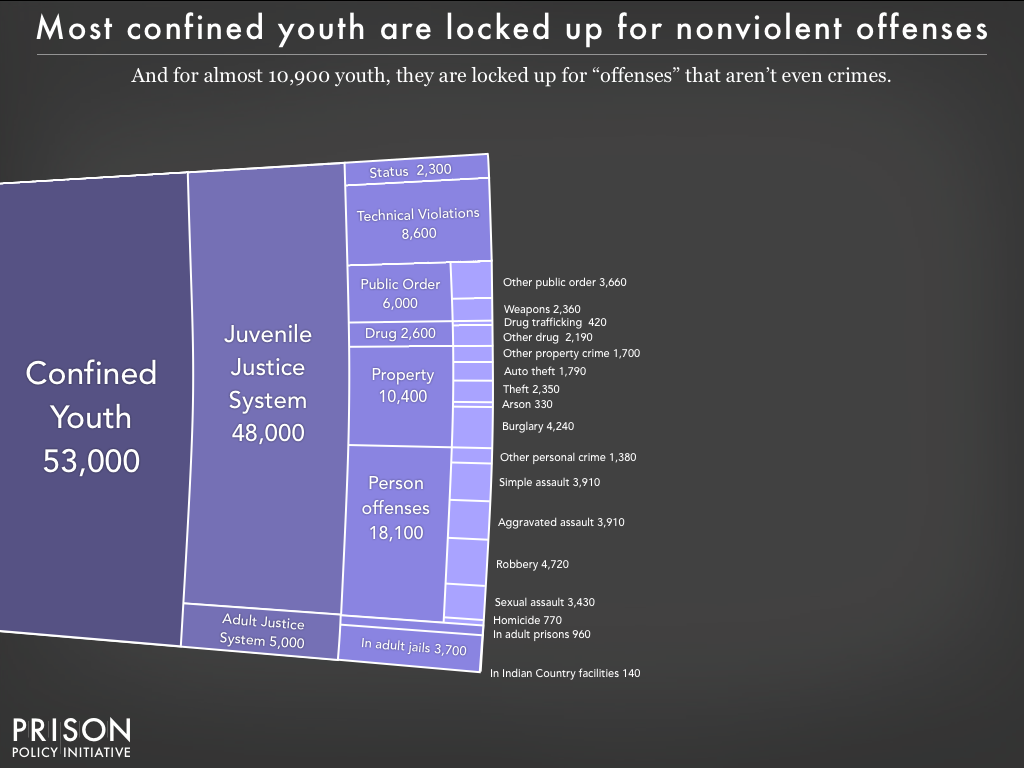

Breaking down incarceration by offense type also exposes some disturbing facts about the youth confined by our criminal and juvenile justice systems: Too many are there for a “most serious offense” that is not even a crime. For example, there are over 8,500 youth behind bars for “technical violations” of the requirements of their probation, rather than for a new offense. Further, 2,300 youth are locked up for “status” offenses, which are “behaviors that are not law violations for adults, such as running away, truancy, and incorrigibility.”9 Nearly 1 in 10 is held in an adult jail or prison, and most of the others are held in juvenile facilities that look and operate a lot like prisons and jails.

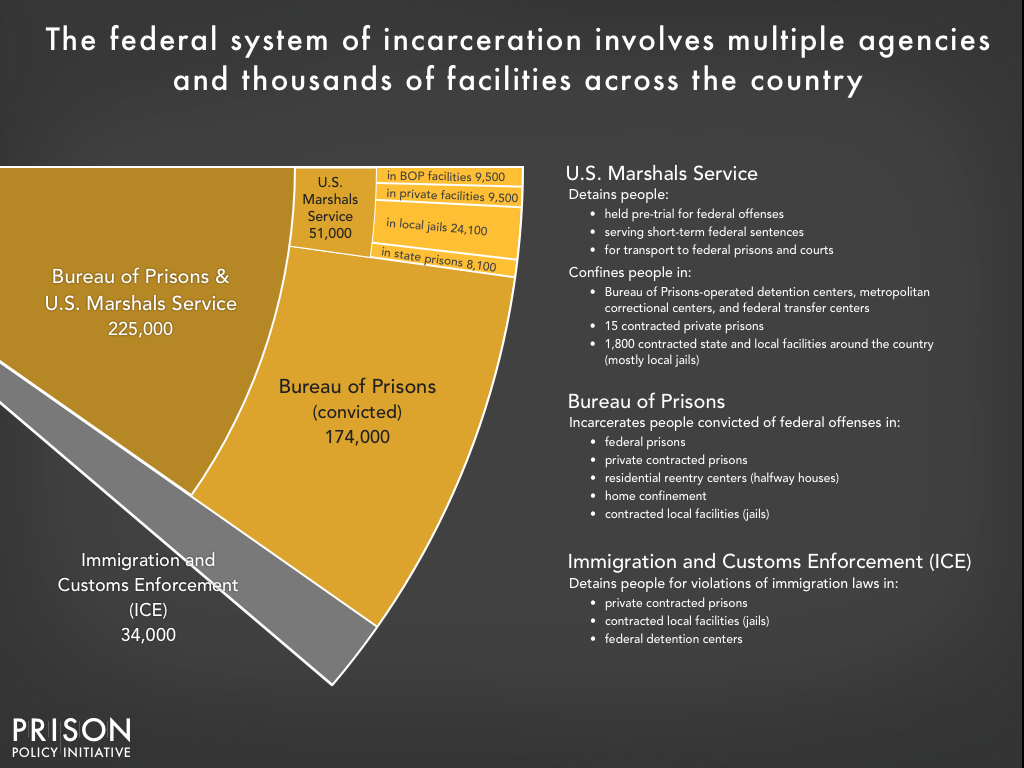

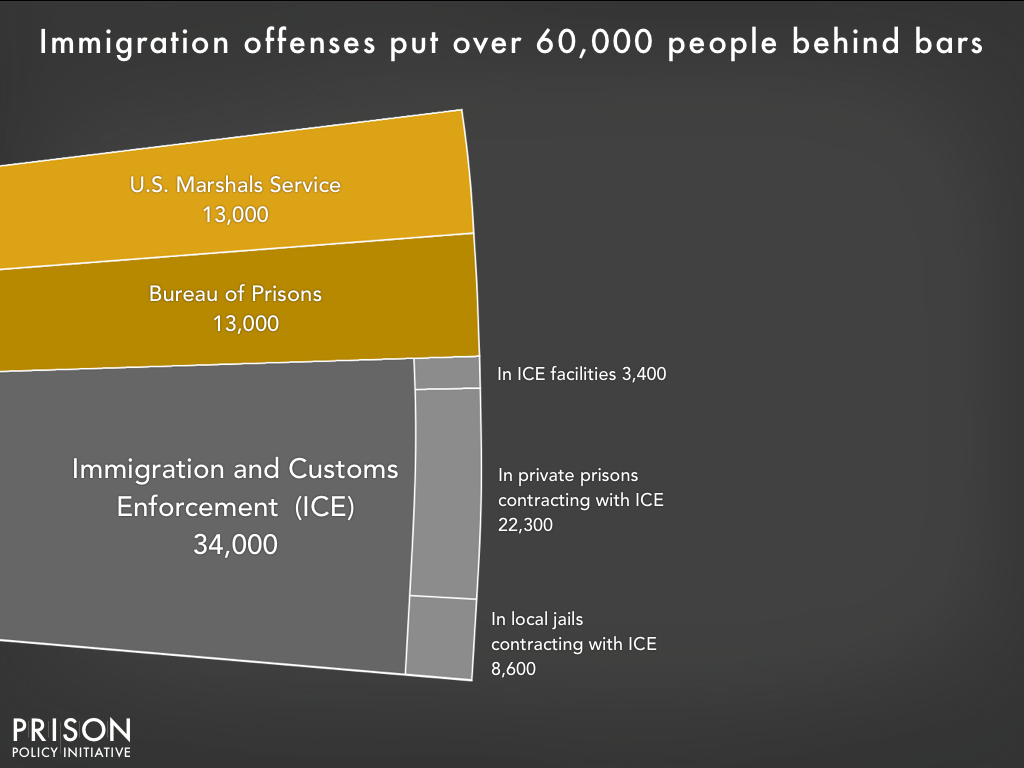

Turning to the people who are locked up criminally and civilly for immigration-related issues, we find that 13,000 people are in federal prison for criminal convictions of violating federal immigration laws, and 13,000 more are held pretrial by U.S. Marshals. Another 34,000 are civilly detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) separate from any criminal proceedings and are physically confined in federally-run or privately-run immigration detention facilities or in local jails under contract with ICE. (Notably, these categories do not include immigrants represented in other pie slices because of non-immigration related criminal convictions.)

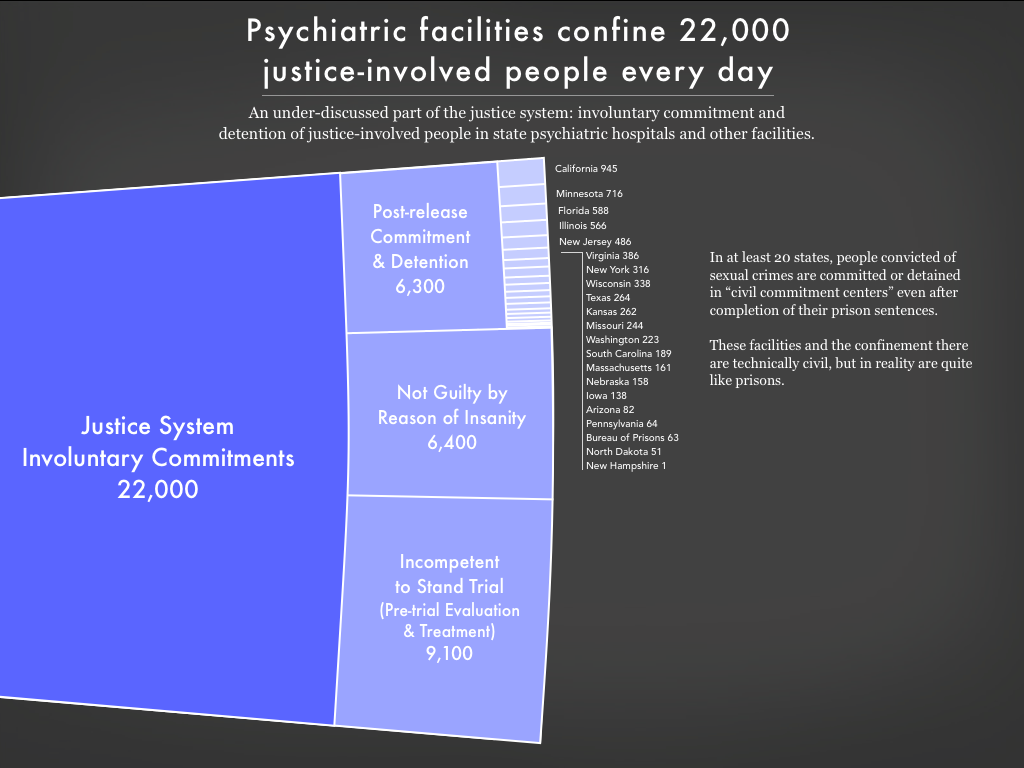

Adding to the universe of people who are confined because of justice system involvement, 22,000 people are involuntarily detained or committed to state psychiatric hospitals and civil commitment centers. Many of these people are not even convicted, and some are held indefinitely. 9,000 are being evaluated pre-trial or treated for incompetency to stand trial; 6,000 have been found not guilty by reason of insanity or guilty but mentally ill; another 6,000 are people convicted of sexual crimes who are involuntarily committed after their prison sentences are complete. While these facilities aren’t typically run by departments of correction, they are in reality much like prisons.

Beyond the “Whole Pie”

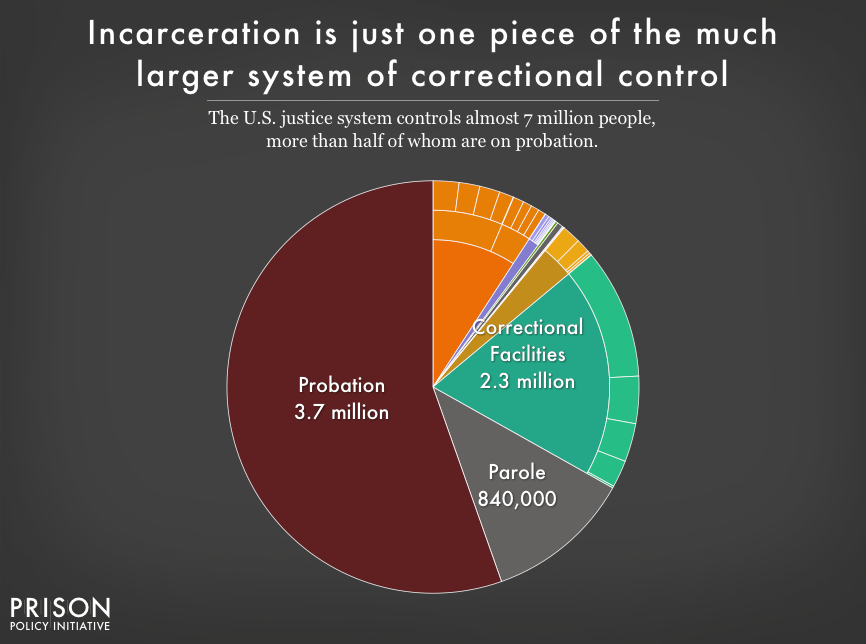

While this “whole pie” provides the most inclusive view of the various systems of confinement in the U.S. justice system available, these snapshots can’t capture all of the important systemic issues. Once we have wrapped our minds around the “whole pie” of mass incarceration, for example, we should zoom out and note that being locked up is just one piece of the larger pie of correctional control. There are another 840,000 people on parole and a staggering 3.7 million people on probation. Particularly given the often onerous conditions of probation, policymakers should be cautious of “alternatives to incarceration” that can easily widen the net of criminalization to people who are not a threat to public safety.

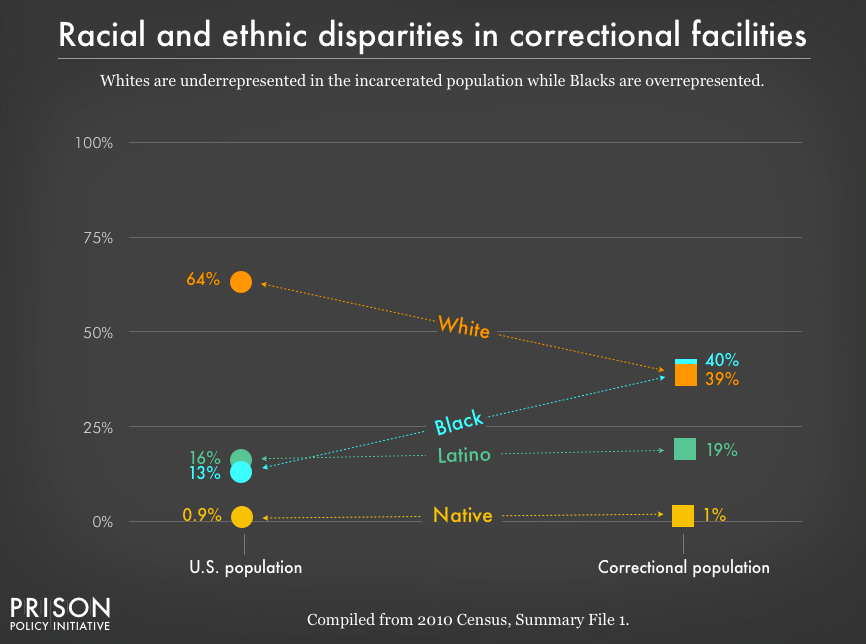

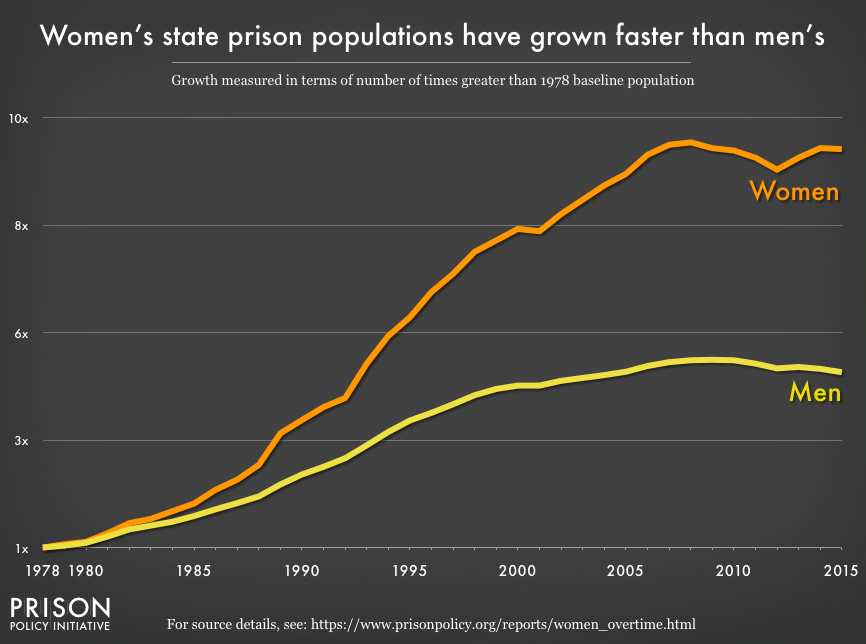

Beyond identifying the parts of the criminal justice system that impact the most people, we should also focus on who is most impacted and who is left behind by policy change. For example, people of color are dramatically overrepresented in the nation’s prisons and jails. These racial disparities are particularly stark for Blacks, who make up 40% of the incarcerated population despite representing only 13% of U.S residents. Gender disparities matter too: rates of incarceration have grown even faster for women than for men. As policymakers continue to push for reforms that reduce incarceration, they should avoid changes that will widen disparities, as has happened with juvenile confinement and with women in state prisons.

Slideshow 4. Swipe for more detail about race and gender disparities.

Now, armed with the big picture of how many people are locked up in the United States, where, and why, we have a better foundation for the long overdue conversation about criminal justice reform. For example, the data makes it clear that ending the War on Drugs will not alone end mass incarceration, but that the federal government and some states have effectively reduced their incarcerated populations by turning to drug policy reform. Looking at the “whole pie” also opens up other conversations about where we should focus our energies:

- What is the role of the federal government in ending mass incarceration? The federal prison system is just a small slice of the total pie, but the federal government can certainly use its financial and ideological power to incentivize and illuminate better paths forward. At the same time, how can elected sheriffs, district attorneys, and judges slow the flow of people into the criminal justice system?

- Are state officials and prosecutors willing to rethink both the War on Drugs and the reflexive policies that have served to increase both the odds of incarceration and length of stay for “violent” offenses?

- Do policymakers and the public have the focus to confront the second largest slice of the pie: the thousands of locally administered jails? And does it even make sense to arrest millions of poor10 people each year11 for minor offenses, make them post money bail, and then lock them up when they can’t afford to pay it? Will our leaders be brave enough to redirect corrections spending to smarter investments like community-based drug treatment and job training?

- Can we implement reforms that both reduce the number of people incarcerated in the U.S. and the well-known racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system?

Now that we can see the big picture of how many people are locked up in the United States in the various types of facilities, we can see that something needs to change. Looking at the big picture requires us to ask if it really makes sense to lock up 2.3 million people on any given day, giving this nation the dubious distinction of having the highest incarceration rate in the world. Both policymakers and the public have the responsibility to carefully consider each individual slice in turn to ask whether legitimate social goals are served by putting each category behind bars, and whether any benefit really outweighs the social and fiscal costs.

Even narrow policy changes, like reforms to money bail, can meaningfully reduce our society’s use of incarceration. Meanwhile, some reforms that seem promising have minimal effect, because they simply transfer people from one slice of the correctional “pie” to another. Keeping the big picture in mind is critical if we hope to develop strategies that actually shrink the “whole pie.”

Read about the data

Read about the data

People new to criminal justice issues might reasonably expect that a big picture analysis like this would be produced not by reform advocates, but by the criminal justice system itself. The unfortunate reality is that there isn’t one centralized criminal justice system to do such an analysis. Instead, even thinking just about adult corrections, we have a federal system, 50 state systems, 3,000+ county systems and 25,000+ municipal systems, and so on. Each of these systems collects data for its own purposes that may or may not be compatible with data from other systems, and that might duplicate or omit people counted by other systems.

This isn’t to discount the work of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which, despite limited resources, undertakes the Herculean task of organizing and standardizing the data on correctional facilities. And it’s not to say that the FBI doesn’t work hard to aggregate and standardize police arrest and crime report data. But the basic reason why so many simple-sounding questions about criminal justice are in fact unanswerable is the “system” wasn’t set up to answer them.

Similarly, there are systems involved in the confinement of justice-involved people that might not consider themselves part of the criminal justice system, but should be included in a holistic view of incarceration. Juvenile justice, civil detention and commitment, and commitment to psychiatric hospitals for criminal justice involvement are examples of this broader universe of confinement. The “whole pie” incorporates data from these systems to provide the most comprehensive view of incarceration possible.

To produce this report, we took the most recent data available for each part of these systems, and where necessary adjusted the data to ensure that each person was only counted once, only once, and in the right place.

Not directly comparable with past pie reports

Before explaining the data sources, we want to explain several methodology changes that make this report not directly comparable with past reports, including:

- For the first time, we found a data source on the number of people in hospitals because a criminal court found them not guilty by reason of insanity (or guilty but mentally ill) and the number of people being held while evaluated pretrial or treated as incompetent to stand trial.

- We changed how we report and display the federal prison system to both include populations that we previously reported elsewhere and to report populations that previously were missed. For the first time, people detained pre-trial in local jails or state prisons for the federal courts are displayed in the federal slice. And for the first time, we were able to use data sources that show the number of people held in Bureau of Prisons jails and federal detainees held in private facilities under contract with the U.S. Marshals Service. (Neither of these last two populations are included in most of the Bureau of Justice Statistics data products on either prisons or jails.)

- We changed our definition of youth confinement to an expansive one that includes all justice placements outside of the home. For the 2016 and 2017 reports, we chose to use the figures for just the most restrictive facility types (youth in detention centers, long-term secure facilities, and reception/diagnostic centers) because these were the most comparable to the typical adult prison. (For more on this, see this section of our report Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie.) However, because our goal is to show the entirety of justice confinement, we have chosen to include all types of juvenile confinement. The inclusion of these less restrictive forms of confinement for youth is consistent with our approach for the adult system which includes the (admittedly far less numerous) halfway houses and other forms of community confinement as a part of the entire adult system.

Data sources

This briefing uses the most recent data available on the number of people in various types of facilities and the most significant charge or conviction. Because not all types of data are collected each year, we sometimes had to, for example, apply the percentage distribution of offense types from the previous year to the current year’s total count data. For this reason, we chose to round most labels in the graphics to the nearest thousand, except where rounding to the nearest ten, nearest one hundred, or (in two cases in the jails detail slide) the nearest 500 was more informative in that context. This rounding process may also result in some parts not adding up precisely to the total.

Our data sources were:

- State prisons: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2016 Table 1 provides the total population as of December 31, 2016, and Table 13 provides data (as of December 31, 2015) that can be used to calculate the ratio of different offense types.

- Jails: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates in 2016 Table 1 and Table 3, reporting average daily population and convicted status for yearend 2016, and our analysis of the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 200212 for offense types. See below and Who is in jail? Deep dive for why we used our own analysis rather than the otherwise excellent Bureau of Justice Statistics analysis of the same dataset, Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002.

- Federal:

- Bureau of Prisons: Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Population Statistics, reporting data as of February 15, 2018 (total population of 183,242), and Prisoners in 2016 Table 15, reporting data as of September 30, 2016 (offense types for the convicted population of 172,554).

- U.S. Marshals Service provides a breakdown of its average daily population in fiscal year 2016 by facility type (state and local, private contracted, federal, and non-paid facilities) on its 2017 Prisoner Operations Fact Sheet. The number held in local jails came from our analysis of the Annual Survey of Jails 2015 data set, which showed that 24,105 people were held for the Marshals Service. We concluded that the number held in state facilities was equal to the difference of the number of jail detainees and the combined “state and local facilities” population reported in the Fact Sheet. Offense data for the Marshals Service was estimated by applying the ratios of offense types from 2013 data reported in César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández’s article “Pretrial Immigration Prisoner Trends, Part 2” to the 2016 population. It is worth noting that the U.S. Marshals detainees held in federal facilities and private contracted facilities were not included in previous editions of this report, as they are not included in most of the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ jails or prisons data sets.

- Youth: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (EZACJRP), reporting data for October 28, 2015. Our data on youth incarcerated in adult prisons comes from Prisoners in 2016 Table 11 and youth in adult jails from Jail Inmates in 2016 Appendix Table 1, both reporting data for December 31, 2016. The number of youth reported in Indian Country facilities comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Jails in Indian Country, 2016 Appendix Table 4, reporting data for June 30, 2016. This edition of The Whole Pie, unlike previous versions, includes all juvenile residential placement facilities included in the EZACJRP data, as explained above. For more information on the geography of the juvenile system, see the Youth First Initiative.

- Immigration detention: The 2016 count of 34,376 comes from page 14 of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Fiscal Year 2018 Congressional Justification. Our estimates of how many ICE detainees are held in federal, private, and local facilities come from the Report of the Subcommittee on Privatized Immigration Detention Facilities, December 1, 2016, by the Homeland Security Advisory Council. Page 6 of that report says that as of September 12, 2016, 10% were in federal owned and operated facilities, 65% in private for-profit contract facilities, and 25% in county jails and other government entities. The ICE 2018 Congressional Justification indicates that the agency’s target average daily population will increase in 2018 to over 51,000, so it is possible the average daily population has already grown.13

- Justice-related involuntary commitment:

- State psychiatric hospitals (people committed to state psychiatric hospitals by courts after being found “not guilty by reason of insanity” (NGRI) or, in some states, “guilty but mentally ill” (GBMI) and others held for pre-trial evaluation or for treatment as “incompetent to stand trial” (IST)): These counts are from pages 92, 99, and 104 of the August 2017 NRI report, Forensic Patients in State Psychiatric Hospitals: 1999-2016, reporting data from 37 states for 2014. The categories NGRI and GBMI are combined in this data set, and for pre-trial, we chose to combine pre-trial evaluation and those receiving services to restore competency for trial, because in most cases, these indicate people who have not yet been convicted or sentenced. This is not a complete view of all justice-related involuntary commitments, but we believe these categories and these facilities capture the largest share.

- Civil detention and commitment (At least 20 states and the federal government operate facilities for the purposes of detaining people convicted of sexual crimes after their sentences are complete. These facilities and the confinement there are technically civil, but in reality are quite like prisons. People under civil commitment are held in custody continuously from the time they start serving their sentence at a correctional facility through their confinement in the civil facility.): The civil commitment counts come from an annual survey conducted by the Sex Offender Civil Commitment Programs Network shared by SOCCPN President Shan Jumper. Except for North Dakota, all counts are from their 2017 survey. North Dakota did not participate in that year’s survey, so we included the state’s figures from the 2016 survey.

- Territorial prisons (correctional facilities in the U.S. Territories of American Samoa, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, and U.S. Commonwealths of Northern Mariana Islands and Puerto Rico): Prisoners in 2016 Table 20, reporting data for December 31, 2016.

- Indian Country (correctional facilities operated by tribal authorities or the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs): Jails in Indian Country, 2016 Table 1, reporting data for June 30, 2016.

- Military: Prisoners in 2016 Tables 18 (for total population) and 19 (for offense types) reporting data as of December 31, 2016.

- Probation and parole: Our counts of the number of people on probation and parole are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Correctional Populations in the United States, 2015 Table 1, Table 5 and Appendix Table 1, reporting data for December 31, 2015, and were adjusted to ensure that people with multiple statuses were counted only once in their most restrictive category. (At the time of publication, newer data collected in 2016 was expected but not yet available.) For readers interested in knowing the total number of people on parole and probation, ignoring any double-counting with other forms of correctional control, there are 870,500 people on parole and 3,789,800 people on probation.

Adjustments to avoid double counting

To avoid counting anyone twice, we performed the following adjustments:

- To avoid anyone in immigration detention being counted twice, we removed the 25% (8,594) of the Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) detained population that is held under contract in local jails from the total jail population. We removed 34.1% of these ICE detainees from the jail convicted population and the balance from the unconvicted population. (We based these percentages of the population held for ICE on our analysis of the Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002, as detailed in our report, Era of Mass Expansion: Why State Officials Should Fight Jail Growth.)

- To avoid anyone in local jails on behalf of state or federal prison authorities from being counted twice, we removed the 83,679 people — cited in Table 17 of Prisoners in 2016 — confined in local jails on behalf of federal or state prison systems from the total jail population and from the numbers we calculated for those in local jails that are convicted. To avoid those being held by the U.S. Marshals Service from being counted twice, we removed 24,105 Marshals detainees from the jail total that we found through our own analysis of the 2015 Annual Survey of Jails dataset. We removed 75.9% of these people held in jails for the Marshals from the jail convicted population, and the balance from the jail unconvicted population. (Again, we based these percentages on our analysis of the Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002.)

- Because we removed ICE detainees and people under the jurisdiction of federal and state authorities from the jail population, we had to recalculate the offense distribution reported in Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002 who were “convicted” or “not convicted” without the people who reported that they were being held on behalf of state authorities, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the U.S. Marshals Service, or U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service/U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).14 Our definition of “convicted” was those who reported that they were “To serve a sentence in this jail,” “To await sentencing for an offense,” or “To await transfer to serve a sentence somewhere else.” Our definition of not convicted was “To stand trial for an offense,” “To await arraignment,” or “To await a hearing for revocation of probation/parole or community release.”

Acknowledgments

All Prison Policy Initiative reports are collaborative endeavors, but this report builds on the successful collaborations of the 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 versions. For this year’s report, the authors are particularly indebted to César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández for his feedback and research pointers on immigration detention, Ann Carson and Todd Minton for helping us understand the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ data on jails, Joshua Aiken for improving our methodology about jail boarding, Jack Donson, Judy Greene, and Carl Takei for helping us identify data on the U.S. Marshals Service, Neelum Arya and Shaena Fazal for guidance on youth confinement, Shan Jumper for sharing updated civil detention and commitment data, and Vera Hollen and Amanda Wik of NRI for answering our questions about the data on forensic patients. This year, we are again grateful to Jordan Miner for making the report interactive, and Elydah Joyce for her help with the design. Any errors or omissions, and final responsibility for all of the many value judgements required to produce a data visualization like this, however, are the sole responsibility of the authors.

We thank the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Safety and Justice Challenge for their support of our research into the use and misuse of jails in this country. We also thank the Public Welfare Foundation and each of our individual donors who give us the resources and the flexibility to quickly turn our insights into new movement resources.

About the authors

Peter Wagner is an attorney and the Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. He co-founded the Prison Policy Initiative in 2001 in order to spark a national discussion about the negative side effects of mass incarceration. His research and advocacy on the issue of prison gerrymandering have led four states and more than 200 local governments to end prison gerrymandering.

Some of his most recent work includes Following the Money of Mass Incarceration, uncovering that prisons are disproportionately built in White areas, and working with Josh Begley to put each state’s overuse of incarceration into the international context.

He is @PWPolicy on Twitter.

Wendy Sawyer is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. She is the author of the 2018 reports Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie and The Gender Divide: Tracking women's state prison growth, as well as the 2016 report Punishing Poverty: The high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. Alongside reports like this that help the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform, the organization leads the nation’s fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (a.k.a. prison gerrymandering) and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone industry and the video visitation industry.

See the footnotes

The number of state and federal facilities is from Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2005, the number of youth facilities is from page 3 of Juvenile Residential Facility Census, 2014, the number of jails from Census of Jails: Population Changes, 1999-2013 and the number of Indian Country jails from Jails in Indian Country, 2016. We aren’t currently aware of a good source of data on the number of the facilities of the other types. ↩

10.6 million jail admissions probably amounts to less than 10.6 million unique individuals cycling through jails in a year. According to a presentation, The Importance of Successful Reentry to Jail Population Growth [Powerpoint] given at The Jail Reentry Roundtable, Bureau of Justice Statistics statistician Allen Beck estimates that of the 12-12.6 million jail admissions in 2004-2005, 9 million were unique individuals. ↩

The local jail population in the main pie chart (614,922) reflects only the population under local jurisdiction; it excludes the people being held in jails for other state and federal agencies. The population under local jurisdiction is smaller than the population (731,300) physically located in jails on an average day in 2016, often called the custody population. (For this distinction, see the second image in the first slideshow above.) The “not convicted” population is driving jail growth. ↩

The data doesn’t show how many people are convicted of drug law violations and are held in territorial prisons or Indian Country jails. ↩

In 2015, there were 1,448,707 drug arrests in the U.S., the far majority of which were for drug possession or use rather than for sale or manufacturing. See Crime in the US 2015 table 29 and the arrests table. ↩

For more on how renting jail space to other agencies skews priorities and fuels jail expansion, see the second part of our report Era of Mass Expansion. ↩

The federal government defines the hierarchy of offenses with felonies higher than misdemeanors. And “[w]ithin these levels, … the hierarchy from most to least serious is as follows: homicide, rape/other sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny/ motor vehicle theft, fraud, drug trafficking, drug possession, weapons offense, driving under the influence, other public-order, and other.” See page 13 Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994. ↩

The felony murder rule has also been applied when the person who died was a participant in the crime. For example, in some jurisdictions, if one of the bank robbers is killed by the police during a chase, the surviving bank robbers can be convicted of felony murder of their colleague. For example see People v. Hudson, 222 Ill. 2d 392 (Ill. 2006) and People v. Klebanowski, 221 Ill. 2d 538 (Ill. 2006) ↩

In 2013, more than half of juvenile status offense cases were for truancy. See page 66 of Juvenile Court Statistics 2013. ↩

Our report on the pre-incarceration incomes of those imprisoned in state prisons, Prisons of Poverty: Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned, found that, in 2014 dollars, incarcerated people had a median annual income that is 41% less than non-incarcerated people of similar ages. Our analysis of similar jail data in Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time found that people in jail have even lower incomes, a median annual income that is 54% less than non-incarcerated people of similar ages. ↩

Recall from above that people go to jail over 11 million times each year. ↩

This is the most recent data available until the Bureau of Justice Statistics begins administering the next Survey of Inmates in Local Jails in 2018. ↩

Notably, the number of people admitted to immigration detention in a year is much higher than the population detained on a particular day. The immigration detention system took in 323,591 people during the course of fiscal year 2016. ↩

Responses to whether someone reported being held for an authority besides a local jail can be found in V113, or V115-V118 in the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 2002 Codebook. ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.