On kickbacks and commissions in the prison and jail phone market

Phone providers are so creative in their influence-peddling that the most viable reform strategies do not focus only on "commissions."

by Peter Wagner and Alexi Jones, February 11, 2019

The prison and jail phone industry is rife with problems – from sky-high phone rates to inexplicable consumer fees to expensive and unnecessary “premium services” – and all of these problems can be traced to a single moment in the industry’s history: When the companies decided to start offering facilities a percentage of their revenue in order to win contracts.

Before long, jails and prisons were prioritizing commissions over low rates when choosing a phone provider. This didn’t just saddle incarcerated people and their families with higher phone rates – it created two major problems for the companies, both of which have caused the market to spiral into dysfunction.

Problem 1: The arms race for higher commissions

Prison phone companies started offering commissions to jails and prisons in order to win contracts from companies that didn’t offer them. What they didn’t expect was that sheriffs would become dependent on this new income. The companies were forced into an “arms race,” competing to give away more and more of their revenue from phone calls; the proffered commissions inched ever closer to 100%.

The companies had painted themselves into a corner: How do you make a profit when you’ve given virtually all of your revenue away? Their solution: Find another source of revenue and hide it from the facility’s management.

That’s why, today, prison and jail phone companies have learned to sustain themselves with revenue entirely separate from phone rates. The first of these hidden sources of revenue is consumer fees – fees to deposit money, open accounts, or get a refund.

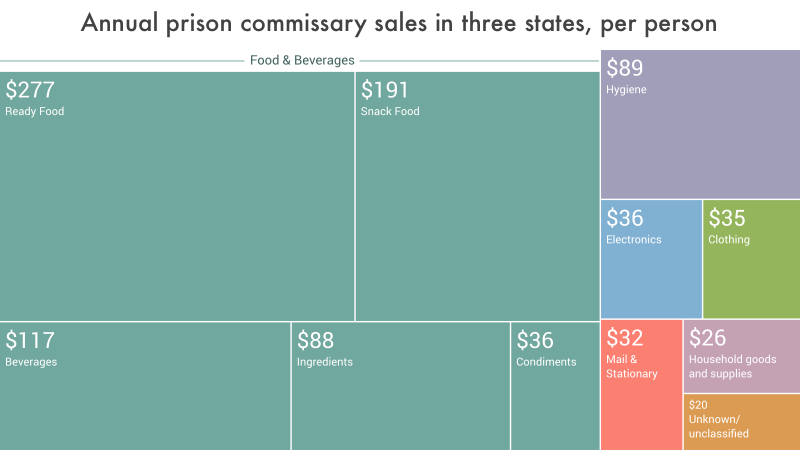

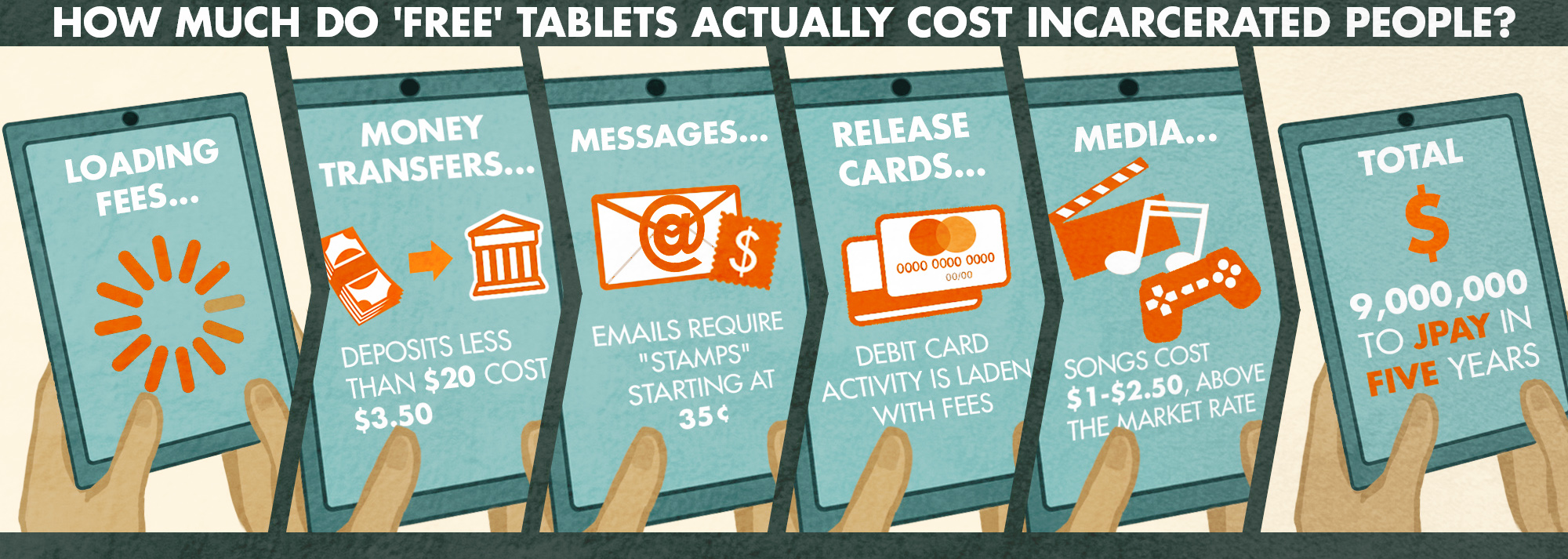

The second source of revenue is a suite of unrelated, profitable services that the companies bundle into phone contracts, such as money transfer, commissary sales, video calls, emails, etc. Most recently, the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision signed a contract for over 50,000 “free” tablet computers, alongside its phone contract with Securus. (The tablets are, of course, not “free” for incarcerated people and their families, who pay to use the tablets and are generating millions in profit for Securus.)

![]() Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

![]() Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

The most extreme – and telling – example so far of the prison phone market’s reliance on extra services comes from a provider named Smart Communications. This year, the Florida-based company began marketing to facilities on a promise of “100% phone commissions.” The catch should be obvious: The provider makes money by bundling other profitable services into the contract, and sharing none of this additional revenue with the facilities.

Such extravagant promises reveal what providers have been doing all along: promising higher and higher commissions by relying more and more heavily on ancillary services and fees to boost profits.

Problem 2: Circumventing new regulations

Gradually, the public has come to understand that there is an inherent conflict of interest when facilities award monopoly contracts and then reap a percentage of the revenue. As a result, the commission system started to fall out of favor. Some – though far from all – state legislatures started to prohibit percentage-based commissions.

But legislatures left open a critical loophole: They didn’t prohibit companies from offering all improper perks to facilities – only commissions.

Instead of paying a fixed percentage of their revenue to the facilities, the companies now use the extra revenue to issue kickbacks in other forms. From the perspective of the poor families paying for the calls, nothing has changed – phone rates remain high – but for the companies, disguising payments in this way makes it harder for journalists and advocates to track the kickbacks. These payments include:

- Paying the facility a “signing bonus” for the contract.

- Paying annual or monthly “administrative fees.”

- Providing phone-related technology, like cell-phone jamming equipment or call recording equipment.

- Providing computer equipment for corrections staff, law libraries and religious services.

- Paying exorbitant “rent” for the vendor’s equipment at a correctional facility.

- Making payments to influential sheriff-led associations (for another example, see page 10 of this document).

- Campaign contributions (read more).

As such, some of the prison and jail systems that have been widely hailed for refusing phone commissions do not, in our opinion, deserve the praise:

- In 2007, the County Commissioners of Dane County, Wisconsin voted to ban the commissions that brought in nearly $1 million per year. The County Supervisor explained, “We’ve lost our moral compass and direction for a million bucks a year.” But in 2009 the county negotiated a new contract where instead of taking a commission, it would just take an “administrative fee” of $476,000 in monthly increments.

- By statute, the California prison system does not take a percentage commission, but it’s quite happy to take cash and cell phone blocking equipment, which was expected to cost GTL between $16.5 million and $33 million to install. (It should also come as no surprise that states with lower phone rates have fewer problems with contraband cell phones and therefore have no need for jamming equipment.)

- Since 2008, the Michigan Department of Corrections has refused percentage commissions. However, in 2011, they raised their rates1 and started requiring that their provider pay money into a “Special Equipment Fund.” As of 2018, this fund takes in $11 million per year, which would amount to a 57% commission. As a result — despite lowering their phone rates in 2018 — Michigan’s phone calls are more expensive calls than 23 states that take traditional commissions.2

Not all hope is lost, of course. Sheriffs and legislatures still have the power to clean up this mess and make the prison and jail phone industry fair for consumers. But to do so, they’ll have to start evaluating phone contracts differently, focusing on more than just percentage commissions. Sheriffs and legislators should also ask whether:

- Consumers are getting a good price for phone calls and ancillary fees.

- The phone contract prohibits the provider from steering calls to more expensive methods.

- The contract does not include other correctional services. (Bundling phone contracts with other things the facility needs makes it impossible for the facility and the families to determine whether the cost for each service is reasonable.)

- The contract does not include “free” products like tablets which are paid for through the sale of “premium” content.

- The contract specifically lists all rates, fees and charges. (It is unfortunately common for facilities to sign contracts without knowing what the provider is going to charge for ancillary fees, or for products that the providers label as “premium” or “convenience”.

Similarly, it can be really tempting to want to ban percentage commissions. We instead suggest two different ways to change the incentives behind these contracts:

- Require contracts to be negotiated on the basis of the lowest price to the consumer. (New York law does this for the state’s prison phone contract.)

- Cap commissions not as a percentage but as a fixed number of cents per minute, say 1 cent a minute. This approach maintains the problematic system of families subsidizing the correctional system, but is in improvement in that it gives the facilities an economic incentive to increase call volume and to monitor their provider for unnecessary fees and services that cut in to call revenue.

Suggested reading for more on the topics here:

- See Prison phone provider accuses Florida Dept. of Corrections of using inmates’ families as a slush fund by Ben Conarck of the Florida Times-Union about how Florida “explicitly prohibited” contract bids that offered a percent commission, and then during negotiations demanded (and received from the winning bidder) a “wish list of goodies” instead of lower rates.

- Our August 1, 2013 letter arguing that the Federal Communications Commission should take an expensive view of “commissions.”” This letter was written when we still thought it practical to prohibit all commissions, but the detail in our letter reviews many of the most egregious examples of commissions packaged under other names.

- Our August 12, 2015 letter to the Federal Communications Commission with our investigation of the industry’s campaign contributions. We make the case that the FCC should focus on lowering the total cost of calls instead of chasing the infinite forms that commissions are taking.

- Our article about the prison phone industry’s new business model: “fee harvesting.” In this 2015 article, we explain why the providers focus on fees and why the facilities have a a real but short-sighted incentive to look the other way.

Footnotes

- Rates changed from 10-12 cents a minute to 18-20 cents with the increase going to the “Special Equipment Fund.” ↩

- These states are: Florida, Hawaii, Colorado, Wisconsin, Idaho, Nevada, Washington, Wyoming, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Maine, South Dakota, North Dakota, Texas, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Virginia, Delaware, Mississippi, Vermont, West Virginia, New Hampshire, and Illinois. The one bright spot in the Michigan contact is that it prohibits deposit fees, which the state estimates will save families $3 million per year. We don’t have a position on whether fee cuts or rate cuts are superior, but to make the best apples-to-apples comparisons, we compared other states to what we GTL would likely have set Michigan’s phone rates at with $3 deposit fees ($0.14/min). ↩

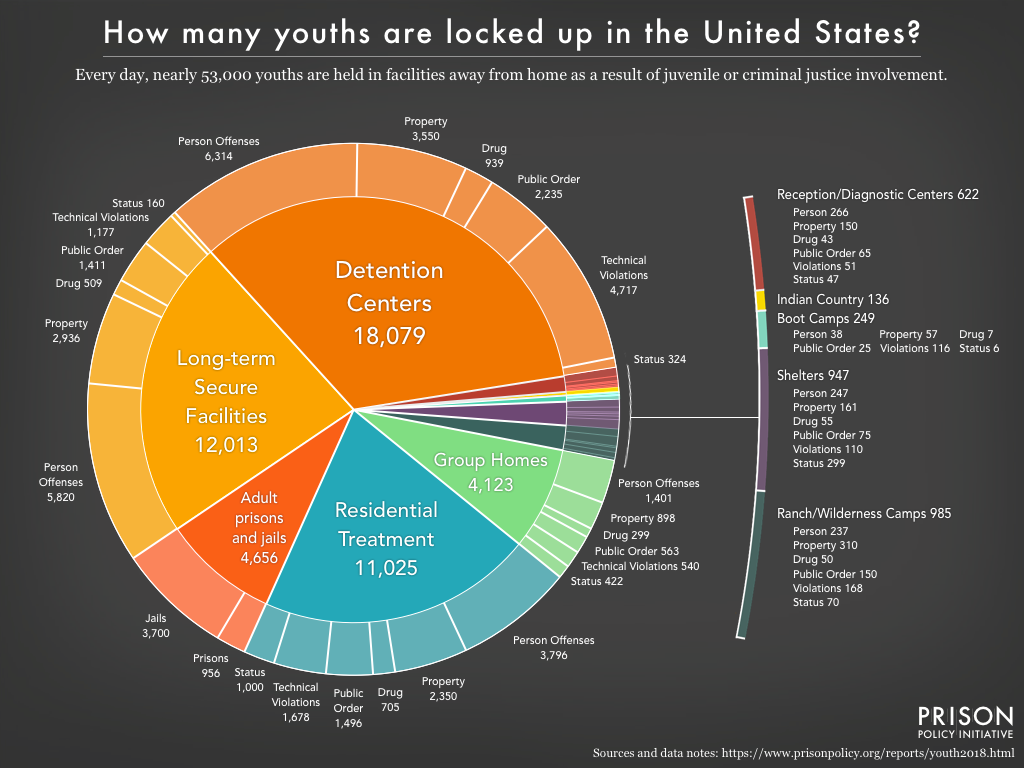

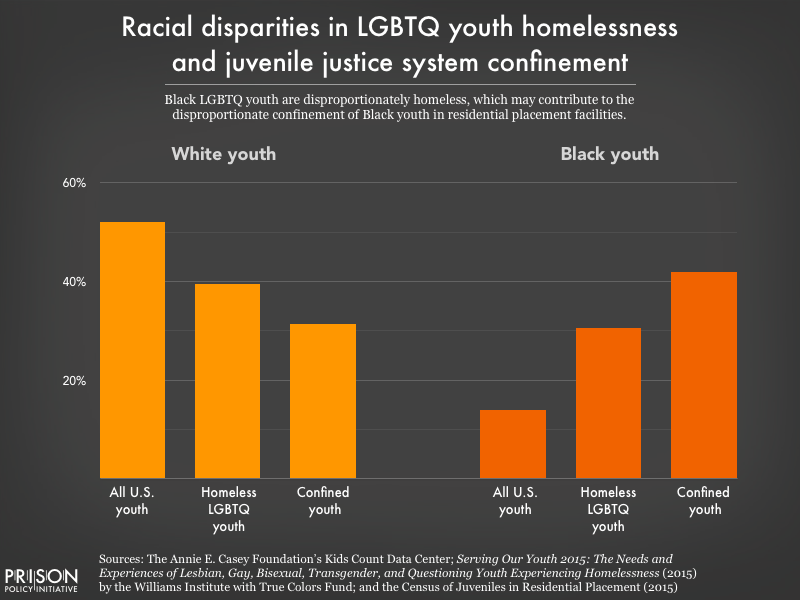

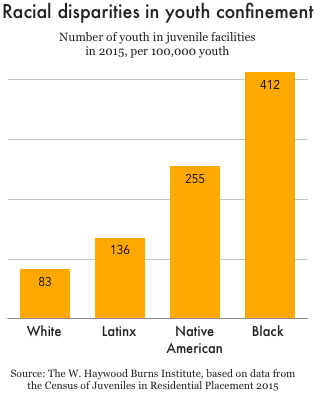

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

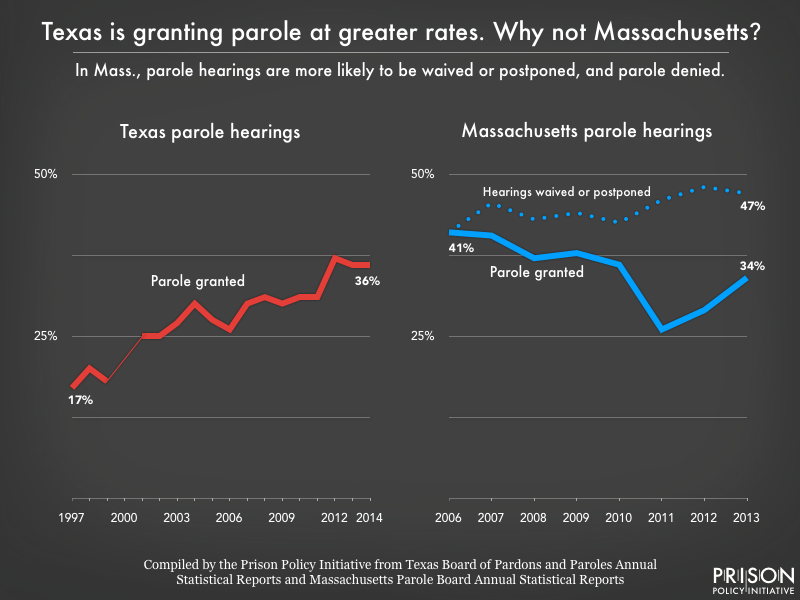

Figure 1. In Texas, the parole grant rate more than doubled between 1997 and 2014 (no data were available for 2000). In Massachusetts, the grant rate fell between 2006 and 2013, while the portion of hearings that were waived or postponed increased, to make up nearly half of all scheduled release hearing outcomes in 2013. (For an explanation of this data, and why our calculated grant rates for Massachusetts are lower than those reported by the state, see the data note at the bottom of this post.)

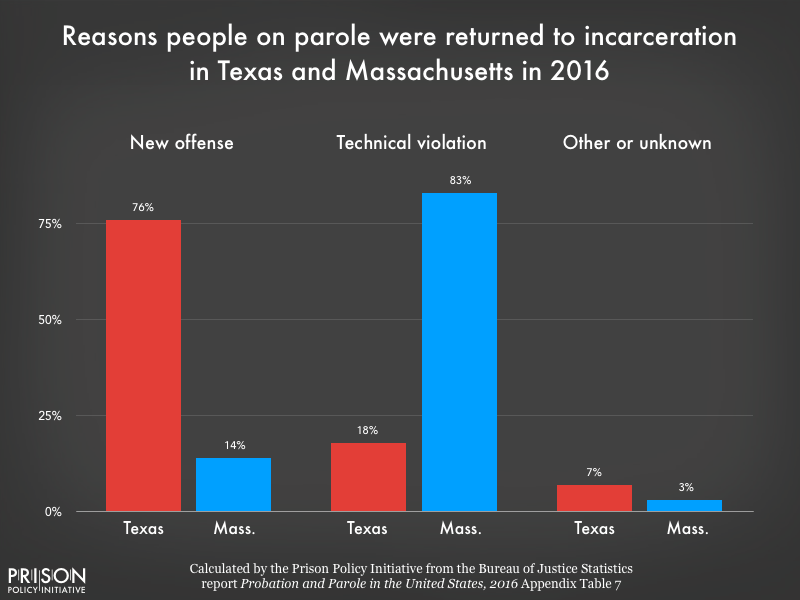

Figure 1. In Texas, the parole grant rate more than doubled between 1997 and 2014 (no data were available for 2000). In Massachusetts, the grant rate fell between 2006 and 2013, while the portion of hearings that were waived or postponed increased, to make up nearly half of all scheduled release hearing outcomes in 2013. (For an explanation of this data, and why our calculated grant rates for Massachusetts are lower than those reported by the state, see the data note at the bottom of this post.) Figure 2. While Texas has a much larger parole population overall, and therefore returned more people to incarceration in 2016, three-quarters of returns to incarceration in Texas were for new offenses. Meanwhile, technical violations accounted for more than 4 out of 5 returns to incarceration from parole in Massachusetts.

Figure 2. While Texas has a much larger parole population overall, and therefore returned more people to incarceration in 2016, three-quarters of returns to incarceration in Texas were for new offenses. Meanwhile, technical violations accounted for more than 4 out of 5 returns to incarceration from parole in Massachusetts.