New data and visualizations spotlight states’ reliance on excessive jailing

We've updated the data tables and graphics from our 2017 report to show just how little has changed in our nation's overuse of jails: too many people are locked up in jails, most detained pretrial and many of them are not even under local jurisdiction.

by Emily Widra, April 15, 2024

- Table of Contents

- Warehousing effect

- Renting jail space

- COVID’s Impact

- Recommendations

- State-specific graphics

- Methodology

- Data appendices

- Footnotes

One out of every three people behind bars is being held in a local jail, yet jails get almost none of the attention that prisons do. In 2017, we published an in-depth analysis of local jail populations in each state: Era of Mass Expansion: Why State Officials Should Fight Jail Growth. We paid particular attention to the various drivers of jail incarceration — including pretrial practices and holding people in local jails for state and federal authorities — and we explained how jails impact our entire criminal legal system and millions of lives every year. In the years since that publication, many states have passed reforms aimed at reducing jail populations, but we still see the same trends playing out: too many people are confined in local jails, and the reasons for their confinement do not justify the overwhelming costs of our nation’s reliance on excessive jailing.

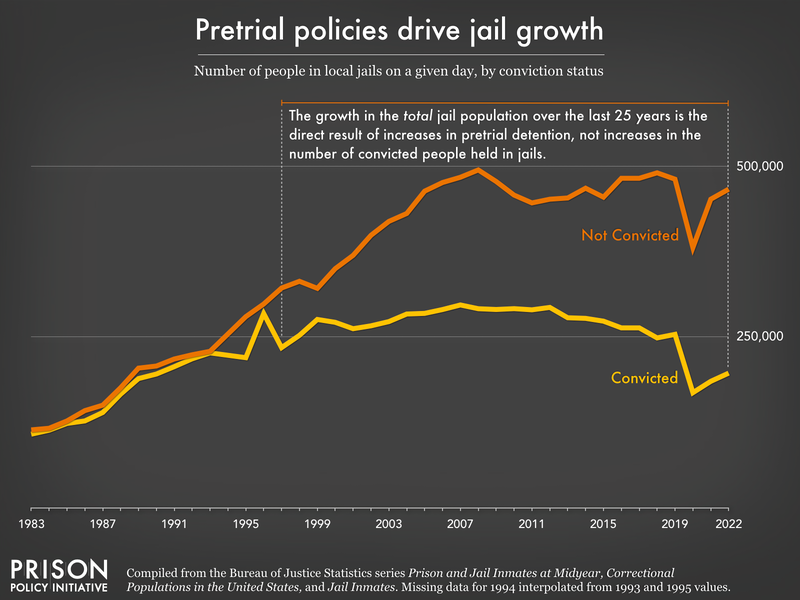

People cycle through local jails more than 7 million1 times each year and they are generally held there for brief, but life-altering, periods of time.2 Most are released in a few hours or days after their arrest, but others are held for months or years,3 often because they are too poor to make bail.4 Fewer than one-third of the 663,100 people in jails on a given day have been convicted5 and are likely serving short sentences of less than a year, most often for misdemeanors. Jail policy is therefore in large part about how people who are legally innocent are treated, and how policymakers think our criminal legal system should respond to low-level offenses.

Pretrial policies have a warehousing effect

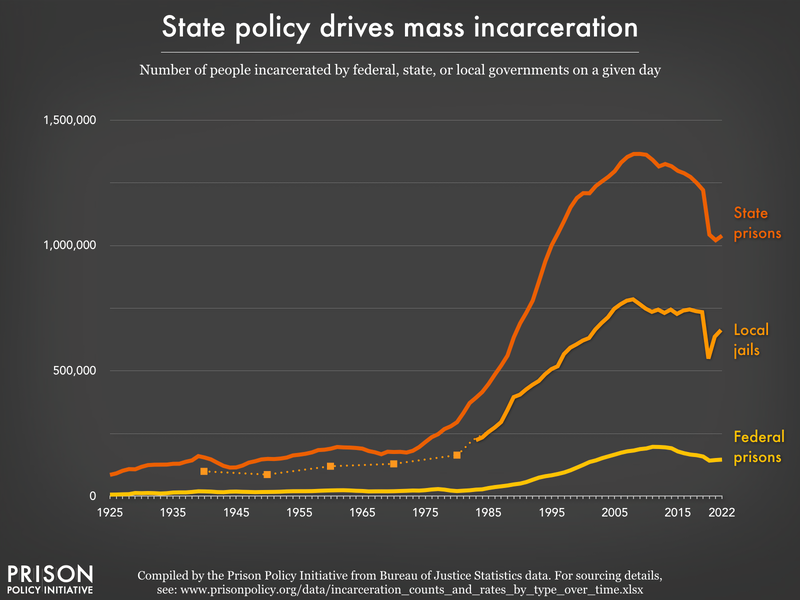

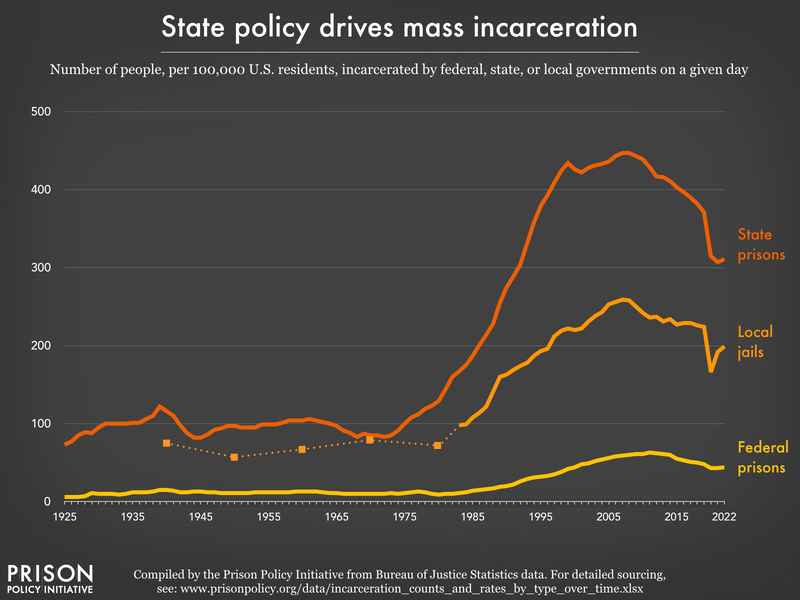

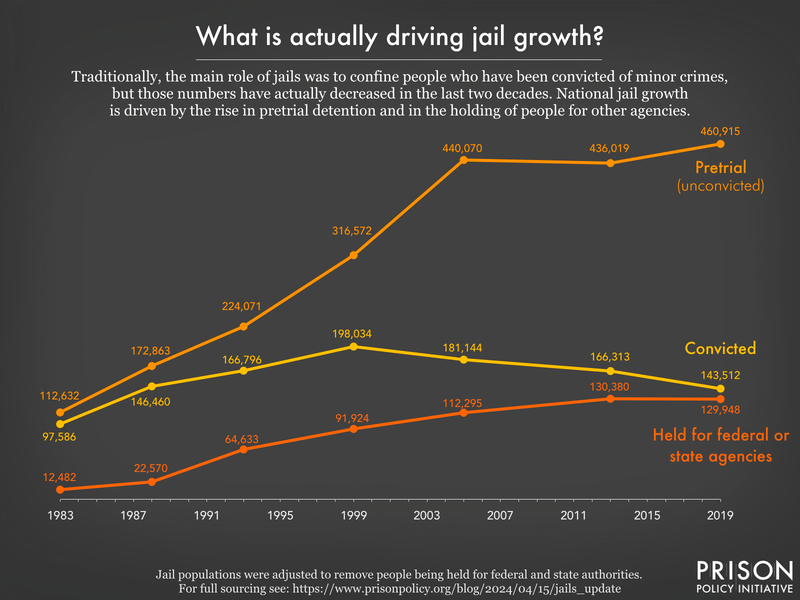

The explosion of jail populations is the result of a broader set of policies that treat the criminal legal system as the default response to all kinds of social problems that the police and jails are ill-equipped to address. In particular, our national reliance on pretrial detention has driven the bulk of jail growth over the past four decades.

More than 460,000 people are currently detained pretrial — in other words, they are legally innocent and awaiting trial. Many of these same people are jailed pretrial simply because they can’t afford money bail, while others remain in detention without a conviction because a state or federal government agency has placed a “hold” on their release.

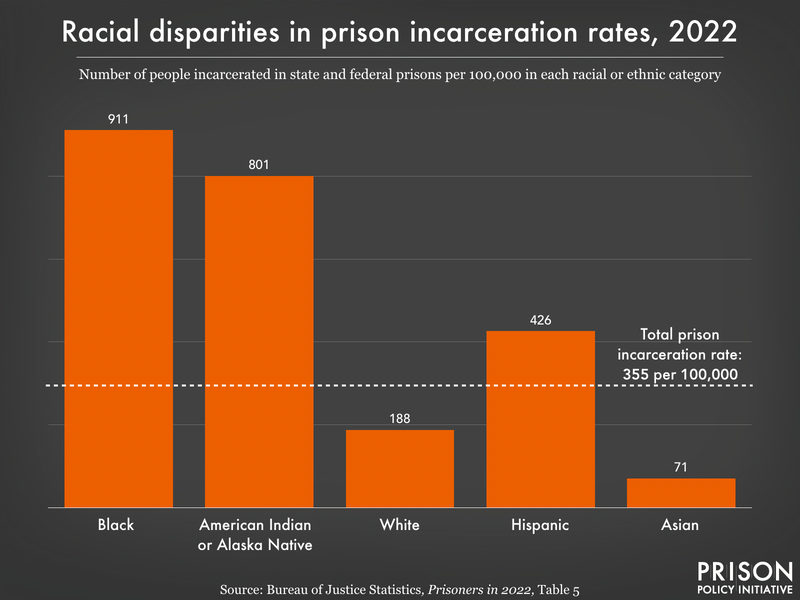

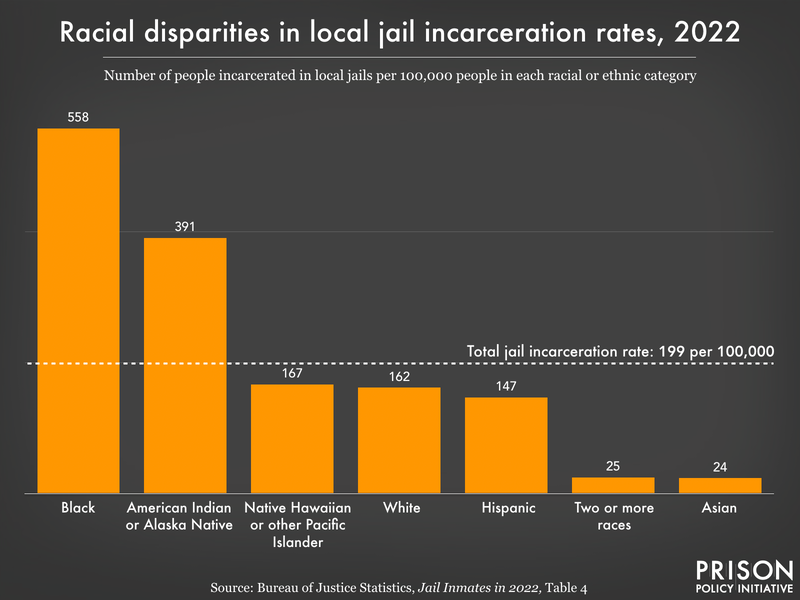

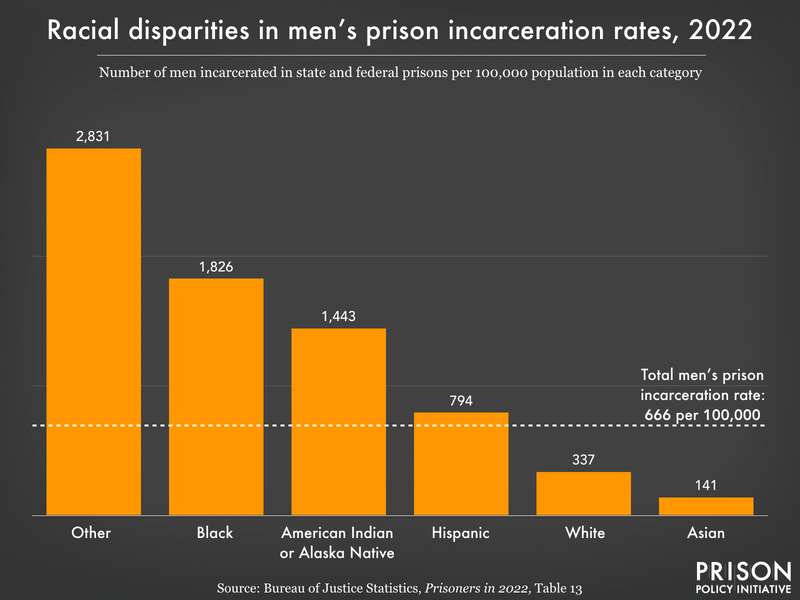

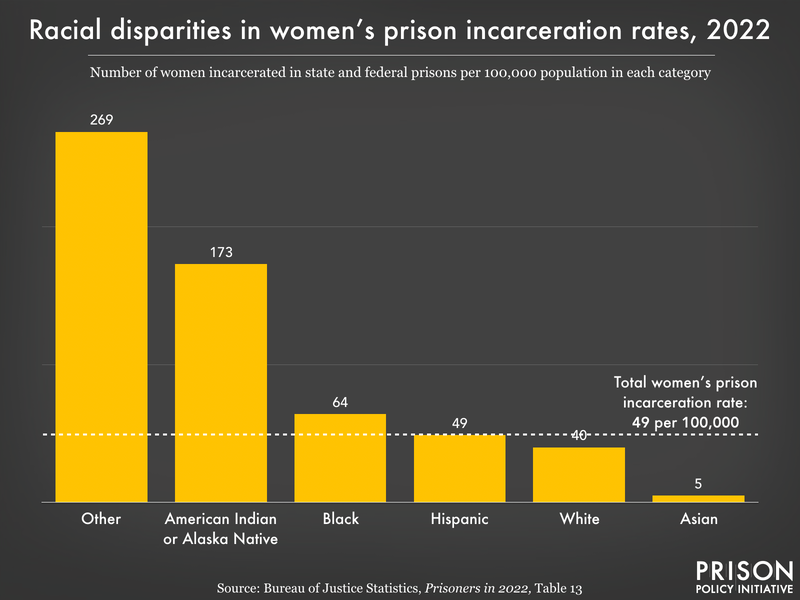

Pretrial detention disproportionately impacts already-marginalized groups of people:

- Low income: The median felony bail amount is $10,000, but 32% of people booked into jail in the past 12 months reported an annual income below $10,000.

- Black people: 43% of people detained pretrial are Black. Black people are jailed at more than three times the rate of white people.

- Health problems: 40% of people in jail reported a current chronic health condition. 18% of people booked into jail at least once in the past 12 months are not covered by any health insurance.

- Mental illness: 45% of people booked into jail in the past 12 months met criteria for any mental illness, compared to only 30% of people who had not been jailed.

- Experiencing homelessness: While national data don’t exist on the number of people in jail who were experiencing homelessness at the time of their arrest, data from Atlanta show that 1 in 8 city jail bookings in 2022 were of people who were experiencing homelessness.

- Lesbian, gay, or bisexual: 15% of people booked into jail in the past 12 months identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, compared to 10% of people not booked in the past year.

This confinement creates problems for individuals on a short-term basis and also has long-term effects. Research in different jurisdictions has found that, compared to similarly-situated peers who are not detained, people detained prior to trial are more likely to plead guilty, be convicted, be sentenced to jail, have longer sentences if incarcerated, and be arrested again. And these harms accrue quickly: being detained pretrial for any amount of time impacts employment, finances, housing, and the well-being of dependent children. In fact, studies have found that pretrial detention is associated with a decreased likelihood of court appearance and an increased likelihood of additional charges for new offenses. There is no question that wholesale pretrial detention does far more harm than good for an increasing number of people and communities.

Renting jail space: a perverse incentive continues to fuel jail growth

There are two different ways to look at jail populations: by custody or jurisdiction. The custody population refers to the number of incarcerated people physically in local jails. The jurisdictional population focuses on the legal authority under which someone is incarcerated, regardless of the type of correctional facility they are in. This means that there are people in the physical custody of local jails, but who are under the jurisdictional authority of another agency, such as the federal government (including the U.S. Marshals Service, immigration authorities, and the Bureau of Prisons) or state agencies (namely the state prison system). For example, immigration authorities can request that local officials notify ICE before a specific individual is released from jail custody and then keep them detained for up to 48 hours after their release date. These holds or “detainers” essentially ask local law enforcement to jail people even when there are no criminal charges pending.

State and federal agencies pay local jails a per diem (per day) fee for each person held on their behalf. For example, in 2024, the state Department of Public Safety and Corrections (prison system) pays local jails in Louisiana $26.39 per person per day, and more than 14,000 people in the Department’s custody were in local jails in 2022. The fees paid by different agencies to confine people in local jails range and depend on the contract between agencies: In 2023, the per diem rate negotiated between Daviess County, Kentucky and the U.S. Marshals Service increased from $55 to $70 per person per day. And these per diem fees can rack up quickly: in fiscal year 2021, the U.S. Marshals Service paid North Carolina counties more than $31 million for jail holds, while the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections spent more than $123 million on their “local housing of adult offenders” program.

In 28 states and the District of Columbia, more than 10% of the jail population is being held on behalf of a state or federal authority. This both skews the data and gives local jail officials a powerful financial incentive to endorse policies that contribute to unnecessary jail expansion. Local sheriffs — who operate jails that are rarely filled to anywhere near their total capacity with people held for local authorities — can pad their budgets by contracting out extra bed space to federal and state governments. To be sure, sharing some jail capacity can be a matter of efficiency: for example, if one county’s jail is occasionally full, borrowing space from a neighboring county may be better than building a larger jail. And, in some states — like Missouri — state law requires that local jails agree to hold people for state or federal agencies. But the systematic renting of jail cells to other jurisdictions — while also building ever-larger facilities in order to cash in on that market6— changes the policy priorities of jail officials, leaving them with little incentive to welcome or implement reforms.

In our 2017 report, we found this phenomenon was most visible in Louisiana, where the state largely outsourced the construction and operation of state prisons to individual parish (county) sheriffs.7 The most recent data suggests that as of 2022, Louisiana, Kentucky, and Mississippi stand out as the worst offenders. In all three states, at least one-third of the state prison population is actually held in local jails (53% in Louisiana, 47% in Kentucky, and 33% in Mississippi).8

Another major consumer of local jail cells is the federal government, starting with the U.S. Marshals Service, which rents about 26,200 jail spaces each year — mostly to hold federal pretrial detainees in locations where there is no federal detention center. In the District of Columbia, South Dakota, New Hampshire, and New Mexico, more than 15% of the statewide jail population was actually held for the U.S. Marshals Service in 2019. Meanwhile, Immigration and Customs Enforcement rents about 15,700 jail spaces each year for people facing deportation.9 In 2019, New Jersey stood out with 16% of the statewide jail population held for immigration authorities, followed by Mississippi (10%).

We should note there is significant geographic variation in just how much of a jail’s population is held for other authorities: more than a quarter of people in rural jails were held for state, federal, or American Indian and Alaska Native tribal governments in 2019, compared to only 11% of people in urban jails.10 The distribution also varies by state, as each has different levels of “excess” jail capacity, and federal officials have specific needs in different parts of the country.

The practice of holding people in local jails for other authorities carries significant personal, social, and fiscal costs, often exposing detained people to the harms of incarceration for longer periods of time than they would be otherwise. Jails are not designed to hold people for any significant period of time; they lack sufficient programming, services, and medical care to house people for months or years.11 This practice also contributes to jail overcrowding, which fuels jail construction and expansion in turn. As scholars Jack Norton, Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, and Judah Schept succinctly put it: “When they build it, they fill it, and counties across the country have been building bigger jails and planning for a future of more criminalization, detention, and incarceration.”

Contextualizing prison and jail population changes during and after the COVID-19 pandemic

Most of the data used in this report come from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of Jails, which was most recently administered in 2019 and published in 2022 (see the methodology for sourcing details). However, the prison population data used to create our state-specific graphics are from 2022 and reveal the dramatic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prison populations in many states over time. They show that state and federal prison admissions dropped 40% in the first year of the pandemic (2020). While not reflected in the 2019 data used in this briefing, we know that by June 2021, jail admissions were down 33% compared to the 12 months ending in June 2019. Before 2020, the number of annual jail admissions was consistently 10 million or more. Because these declines were not generally due to permanent policy changes, we expect that both prison and jail admissions will return to pre-pandemic levels as cases that were delayed for pandemic-related reasons work their way through the court system.

Recommendations

Our recommendations from 2017 remain just as relevant today, and can help state and local officials move away from using jails as catch-all responses to problems that disproportionately impact poor and marginalized communities:

Change offenses and how offenses are treated

- States should reclassify criminal offenses and turn charges that don’t threaten public safety into non-jailable infractions.12

- For other offenses, states should create a presumption of citation, in lieu of arrests, for certain low-level crimes.13

- For low-level crimes where substance abuse and/or mental illnesses are involved, states should make community treatment-based diversion programs the default instead of jail.14 States should also fully fund these diversion programs.15

Help people successfully navigate the criminal legal system to more positive outcomes

- States should immediately set up pilot projects to test promising programs that facilitate successful navigation of the criminal legal system. Court notification systems and other “wrap-around” pretrial services often increase court appearances while also reducing recidivism.16

Change policies that criminalize poverty or that create financial incentives for unnecessarily punitive policies

- States should eliminate the two-track system of justice by abolishing money bail. States that are not ready to take that step should start by abolishing the for-profit bail industry in their state, and providing technical resources to existing local-level bail alternative programs to help these programs self-evaluate and improve state-level knowledge.17

Address the troubling trend of renting jail space

- States should evaluate whether the renting of local jail space to state and federal authorities is steering local officials away from effectively addressing local needs.18

Updated state-specific graphics

In 2017, we argued that if lawmakers want criminal legal system reform, they must pay attention to jails. Years later, this remains true. To help state officials and state-level advocates craft reform strategies appropriate for their unique situations, this report offers updated data and state-specific graphs on conviction status, as well as changes in incarceration rates and populations in both prisons and jails.

The graphs made for this briefing are included in our profiles for each state:

and are available individually from this list:

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Alabama, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Alabama, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Alabama, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Arizona, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Arizona, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Arizona, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Arkansas, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Arkansas, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Arkansas, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in California, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in California, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in California, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Colorado, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Colorado, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Colorado, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in the District of Columbia, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in the District of Columbia, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in the District of Columbia, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Florida, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Florida, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Florida, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Georgia, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Georgia, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Georgia, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Idaho, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Idaho, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Idaho, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Illinois, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Illinois, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Illinois, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Indiana, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Indiana, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Indiana, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Iowa, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Iowa, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Iowa, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Kansas, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Kansas, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Kansas, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Kentucky, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Kentucky, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Kentucky, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Louisiana, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Louisiana, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Louisiana, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Maine, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Maine, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Maine, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Maryland, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Maryland, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Maryland, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Massachusetts, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Massachusetts, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Massachusetts, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Michigan, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Michigan, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Michigan, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Minnesota, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Minnesota, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Minnesota, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Mississippi, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Mississippi, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Mississippi, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Missouri, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Missouri, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Missouri, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Montana, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Montana, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Montana, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Nebraska, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Nebraska, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Nebraska, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Nevada, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Nevada, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Nevada, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in New Hampshire, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in New Hampshire, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in New Hampshire, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in New Jersey, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in New Jersey, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in New Jersey, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in New Mexico, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in New Mexico, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in New Mexico, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in New York, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in New York, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in New York, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in North Carolina, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in North Carolina, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in North Carolina, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in North Dakota, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in North Dakota, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in North Dakota, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Ohio, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Ohio, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Ohio, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Oklahoma, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Oklahoma, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Oklahoma, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Oregon, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Oregon, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Oregon, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Pennsylvania, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Pennsylvania, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Pennsylvania, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in South Carolina, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in South Carolina, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in South Carolina, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in South Dakota, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in South Dakota, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in South Dakota, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Tennessee, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Tennessee, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Tennessee, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Texas, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Texas, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Texas, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Utah, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Utah, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Utah, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Virginia, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Virginia, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Virginia, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Washington, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Washington, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Washington, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in West Virginia, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in West Virginia, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in West Virginia, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Wisconsin, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Wisconsin, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Wisconsin, 1978-2019

- Jail and prison incarceration rates in Wyoming, 1978-2022

- Jail and prison population in Wyoming, 1978-2022

- Jail conviction status in Wyoming, 1978-2019

Methodology

Jails are, by definition, a distributed mess of “systems,” so accessing relevant data can be a challenge. Jails often hold people for other (state and federal) agencies and, at times, the numbers can be large enough to obscure the results of state- and local-level policy changes. For that reason, this report takes the time to separate out people held in jails for state prison systems or federal agencies, such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Bureau of Prisons, the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Our national data come from our own analysis of multiple Bureau of Justice Statistics datasets. The National Jail Census series provides the most complete annual snapshot of jail populations. Our state-level data are from the Census of Jails for the years 1983, 1988, 1993, 1999, 2005, 2013, and 2019, and the Deaths in Custody Reporting series (now called Mortality in Correctional Institutions) for the years 2000-2004, 2006-2012, and 2014-2018. (We considered using the Annual Survey of Jails for our state-level data, but the Bureau of Justice Statistics explains that this dataset was “designed to produce only national estimates” and, after much testing, we concluded that this dataset could not reliably be used for state-level summaries.) There are no comparable data available for state-by-state jail population comparisons published more recently than 2019. 19

Jails — or facilities that serve the functions of jails — operate in all states, but in six states (Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont) most or all of the jail system is integrated into the state prison system, so the “jail” populations in those states are not reflected in the federal data products on which this report relies (they are instead counted in the annual prison data). For that reason, we are unable to report state-specific data for those states, and those states are not included in the national totals reported in this report. Because these six states are relatively small in terms of population, we do not think their exclusion meaningfully impacts the national totals nor the much more important analysis of the trends within the national totals.

Many of our data sources are labeled on the individual graphics, but in some cases we had to combine multiple datasets or perform complicated adjustments where additional detail would be helpful to other researchers and advocates:

National data:

- National number of people held in local jails for state and federal agencies (also referred to as “boarding” or “renting”):

- National number of people held in local jails for all of the various federal authorities, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs: We have national-level data for 1983, 1988, 1993, 1999, 2005, 2013, and 2019. For those years, we used the National Jail Census series for the number of people held in local jails for the Bureau of Prisons or U.S. Marshals Service and for immigration authorities. For 2002-2005, 2007-2013, 2017-2018, and 2020-2022, the number of people held in local jails for immigration authorities comes from the Annual Survey of Jails series. For years between the National Jail Census series — when we were not able to find compatible data — we estimated the populations based on a linear trajectory. The estimates are noted in the appropriate appendix tables to differentiate them from the reported data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- National number of people held in local jails for state authorities: The Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners series (1983-2022) publishes the number of people held in local jails for state authorities and this data is available for every year from 1983 to 2022. (This data point is also collected in the Census of Jails and the Annual Survey of Jails but we concluded, after much study, that the Prisoners series, based on data collected directly from states’ Departments of Corrections, was more reliable and more frequently collected and published.)20

- National pretrial and jail sentenced populations: Total numbers for each category are reported in the National Jail Census series (1983, 1988, 1993, 1999, 2005, 2013, and 2019). We then adjusted the reported figures for the convicted and unconvicted populations to remove those held for other agencies from these jail totals. For years between the National Jail Census series — when we were not able to find compatible data — we estimated the populations based on a linear trajectory. The estimates are noted in the appropriate appendix tables to differentiate them from the reported data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- We removed 100% of people held for state prison systems (all of whom have been convicted and sentenced to prison terms) from the jail convicted totals (everyone else who has been convicted but not sentenced to prison).

- We removed 34.1% of the people being held under the authority of Immigration and Customs Enforcement from the jail convicted population and removed the balance from the jail unconvicted population. (We based these percentages of the population held for ICE on our analysis of the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 2002. We found 34.1% of ICE detainees were there “to await sentencing for an offense,” “to await transfer to serve a sentence somewhere else,” “to serve a sentence in this jail,” or “to await a hearing for revocation of probation/parole or community release.”) This percentage calculation ignored any respondent who did not answer the question, and counted anyone who answered both a “convicted” and “unconvicted” status as convicted. We deliberately used this methodology which counts those awaiting revocation hearings as “convicted” because that matches the methodology used in our main dataset for this project: the National Jail Census. (Not surprisingly, since the people detained for ICE were answering a survey intended for criminal legal system populations, the leading response (41%) for ICE detainees about why they are being held in jail, after being read a list of statuses like “to serve a sentence” or “to await arraignment” was to answer “for another reason.”)

- We removed 75.9% of the people being held for either the Bureau of Prisons or the U.S. Marshals Service from the jail convicted population and we removed the balance from the jail unconvicted population. (We based these percentages on our analysis of the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 2002 as described above for people detained for ICE).

State data:

Our historical, state-specific data on prisons, jails, and the changes in jail composition come from several different data sources:

- For the state-level graphs on the jail and prison populations, the jail populations are based on the National Jail Census series for the years 1978, 1983, 1988, 1993, 1999, 2005, 2013, and 2019 and the Deaths in Custody Reporting series (now called Mortality in Correctional Institutions) for 2000-2004, 2006-2012, and 2014-2018. For years between the National Jail Census series — when we were not able to find compatible data — we estimated the populations based on a linear trajectory. The estimates are noted in the appropriate appendix tables to differentiate them from the reported data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. As described above, our jail population totals were adjusted to remove people held for state or federal authorities in order to focus on those held by local authorities under local jurisdiction. The number of people in state prisons comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Statistical Analysis Tool — Prisoners for 1978-2019 and Table 2 of Prisoners in 2020, Prisoners in 2021, and Prisoners in 2022 for 2020-2022. Of note, people sentenced for felonies in the District of Columbia were transferred to the Federal Bureau of Prisons as of December 2001, so there is no prison population or rate for the District for 2001-2022.

- For the state-level graphs on jail and prison incarceration rates, for the jail populations in each state we divided the above (adjusted) numbers by the July 1st U.S. Census Bureau’s Census Vintage Population Estimates, which we have published in Appendix Table 6, and multiplied the result by 100,000 to show an incarceration rate per 100,000 people in each state for each year on the graph. The jail populations used in this report were collected on June 30th (“midyear”) for most years, so we used U.S. Census Bureau population estimates from July 1st for each year. Our state prison incarceration rates come from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Statistical Analysis Tool — Prisoners for 1978-2019 and Table 7 of Prisoners in 2020, Prisoners in 2021, and Prisoners in 2022 for 2020-2022. Of note, people sentenced for felonies in the District of Columbia were transferred to the Federal Bureau of Prisons as of December 2001, so there is no prison population or rate for the District for 2001-2022.

- For the state graphs of the number of people incarcerated in local jails by conviction status, we calculated estimates of the number of people held for local authorities by conviction status without including people held for federal or state authorities. The Census of Jails does not report the conviction status of people held for other authorities separately from those held for local authorities, so we based our estimate on the only reported ratio of convicted/unconvicted which includes the entire custody population. (We concluded that our national estimates of the portion of people held for state prisons or various federal agencies that are convicted or unconvicted were not reliable at the state level, so we used a simpler methodology for our state graphs.) To create this estimate, we determined the percentages of all people being held in jails in each state who were convicted and unconvicted in the National Jail Census series (1978, 1983, 1988, 1993, 1999, 2005 and 2013). We then subtracted the number of people held for state or federal authorities from the total statewide jail population, and applied our percentage convicted/unconvicted to the remainder. Because most people in jails being held for other authorities are convicted, we believe, our figures likely undercount the unconvicted/pretrial populations and overcount the convicted populations.

For the six states where the federal government can not provide jail counts or conviction status data, we only graphed the state prison portions.

Appendix tables

- Appendix Table 1. U.S. jail conviction status

- Appendix Table 2. Jail trends by state

- Appendix Table 3. Jail conviction status over time by state

- Appendix Table 4. Jail and prison incarceration rates over time by state

- Appendix Table 5. Jail and prison incarcerated populations over time by state

- Appendix Table 6. July 1 state population estimates

Footnotes

-

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates in 2022, Table 1. ↩

-

Pretrial detention — for any amount of time — impacts employment, finances, housing, and the well-being of dependent children. In addition, jail stays are life-threatening: from 2000 to 2019, over 20,000 people died in local jails. In 2019 alone, more than one thousand people died in local jails. ↩

-

Jail stays are increasing in length: in 2022, people spent 8 more days in jail (32.5 days) on average than they did in 2015 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates in 2022, Appendix Table 1). ↩

-

When he was 16 years old, Kalief Browder was held in New York City’s Rikers Island jail for three years, including almost two years in solitary confinement, because his family could not afford his $3,000 bail. ↩

-

Among the 663,100 people in jail on June 30, 2022, 70% (466,100) were unconvicted and held pretrial (Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates in 2022, Table 5). However, 2019 is the most recent year for which jail data can be adjusted to exclude the people being held by federal and state authorities. This adjustment of 2019 jail data reveals that in 2019, 76% of the 604,400 people in jail held for local authorities were unconvicted (pretrial). See Figure 1. ↩

-

For example, in Bladen County, North Carolina, a newly built jail had earned the county nearly $2 million in the first 18 months of renting jail beds to the federal government in 2019. At the time of our 2017 report, a clear example of this pattern took place when officials in Blount County, Tennessee used “jail overcrowding” to justify a 2016 proposal for jail expansion. A deeper analysis, however, revealed that the county’s jail was overcrowded in large part because it was renting space to the state prison system. The county then cut back on renting space to the state prison system and reportedly explored other ways to reduce its jail population in place of jail expansions (we have not found evidence of a new jail or expanded jail in Blount County as of March 2024). ↩

-

Louisiana’s jail building boom appears to have been entirely fueled by the pursuit of contracts with the state’s prison system. As The Times-Picayune has explained, “In the early 1990s, when the incarceration rate was half what it is now, Louisiana was at a crossroads. Under a federal court order to reduce overcrowding, the state had two choices: Lock up fewer people or build more prisons. […] It achieved the latter, not with new state prisons — there was no money for that — but by encouraging sheriffs to foot the construction bills in return for future profits.” ↩

-

In terms of the impact on local jail populations, in 2019 (the most recent year with this data) people held in jails for state prison systems accounted for 29% of jail populations statewide in Mississippi, 30% in Louisiana, and 41% in Kentucky (Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2022, Table 14, and Census of Jails, 2005-2019, Table 12). ↩

-

These detainers, or “immigration holds,” request that local officials notify ICE before a specific individual is released from jail custody and then to keep them there for up to 48 hours after their release date, basically asking local law enforcement to jail people even when there are no criminal charges pending. For more details, see our 2020 explainer on these practices. ↩

-

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Jails, 2005-2019 — Statistical Tables, Table 13. ↩

-

Christopher Blackwell highlights a number of differences in conditions of confinement between jails and prisons in his 2023 editorial for the New York Times: “Two Decades of Prison Did Not Prepare Me for the Horrors of County Jail.” ↩

-

For example California, Massachusetts, and Ohio have reduced offenses from minor misdemeanors to non-jailable infractions. ↩

-

For example, while all states allow citation in lieu of arrest for misdemeanors, only a handful of states permit citations for some felonies or do not broadly exclude felonies. See the National Conference of State Legislatures, 50 State Chart on Citation In Lieu of Arrest, last updated on March 18, 2019. ↩

-

For example, in Pima County, Arizona, as part of the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, officials have begun screening people for mental health and substance abuse concerns who are arrested before their initial court appearance. Other diversion programs, such as Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) programs, coordinate the efforts of local law enforcement agencies with community-based service providers in counties like Multnomah County, Oregon. For more on LEAD programs, see the Addiction Policy Forum, Center for Health and Justice, National Criminal Justice Association “Innovation Spotlight: Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion.” ↩

-

For example, diversion programs have been shown to be a cost-saving reform by reducing caseloads, but are often defunded due to budget shortfalls. States creating these programs should also ensure that diversion programs don’t turn into revenue-generating schemes. ↩

-

For more examples of practical interventions to improve court appearance rates, see the National Guide to Improving Court Appearances from ideas42, published in May 2023. ↩

-

For example, four states have abolished commercial bail: Illinois, Kentucky, Oregon, and Wisconsin. ↩

-

For example, a recent California bill would prevent local jails from receiving state grant funding that is intended for expanding and improving jail facilities if those expansions were for the purpose of renting space to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. ↩

-

For readers wondering when the next state-level data will be collected and published, the Bureau of Justice Statistics is planning a 2024 Census of Jails collection and has proposed replacing the Annual Survey of Jails with a more concise annual Census of Jails thereafter. The data are typically published about two years after collection. ↩

-

Please note that because our methodology is not the same as the Bureau of Justice Statistics, some numbers used in this publication differ from the published data in the Census of Jails, 2005-2019 — Statistical Tables. ↩