Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023

By Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner

March 14, 2023

Press release

This report is old. See our new version.

- Sections

- The big picture

- The impact of COVID

- 9 Myths

- High costs of low-level offenses

- Youth, immigration & involuntary commitment

- Beyond the Pie: Community supervision, poverty, race, and gender

- Necessary reforms

- Sources

Can it really be true that most people in jail are legally innocent? How much of mass incarceration is a result of the war on drugs, or the profit motives of private prisons? How has the COVID-19 pandemic changed decisions about how people are punished when they break the law? These essential questions are harder to answer than you might expect. The various government agencies involved in the criminal legal system collect a lot of data, but very little is designed to help policymakers or the public understand what’s going on. As public support for criminal justice reform continues to build — and as the pandemic raises the stakes higher — it’s more important than ever that we get the facts straight and understand the big picture.

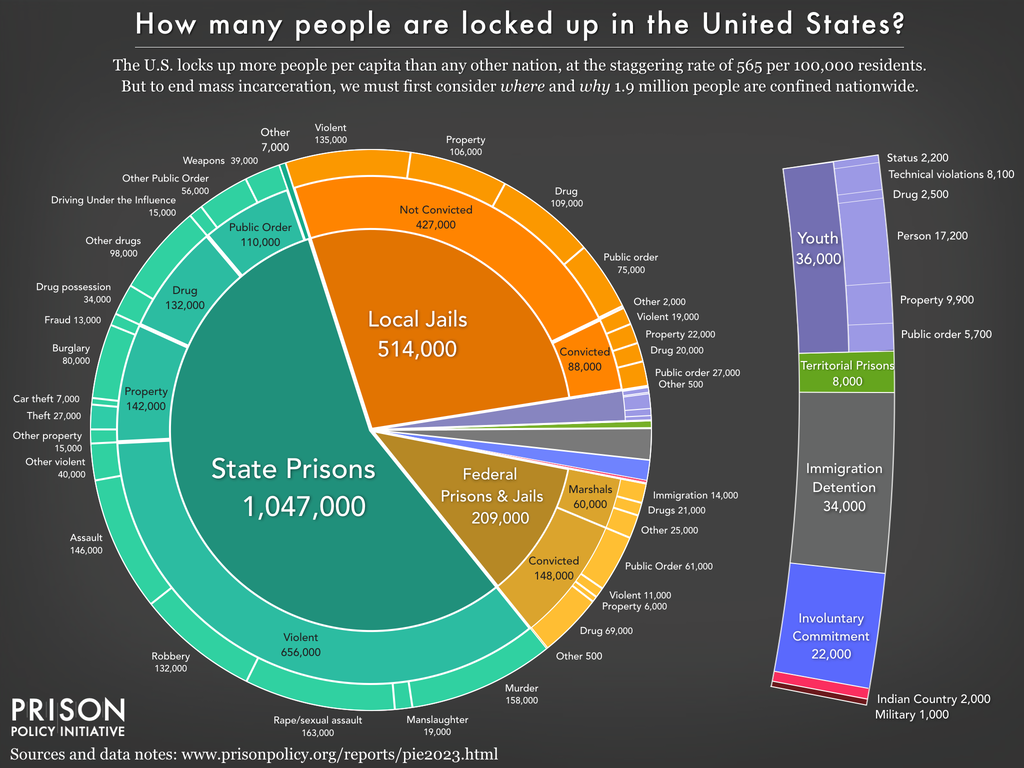

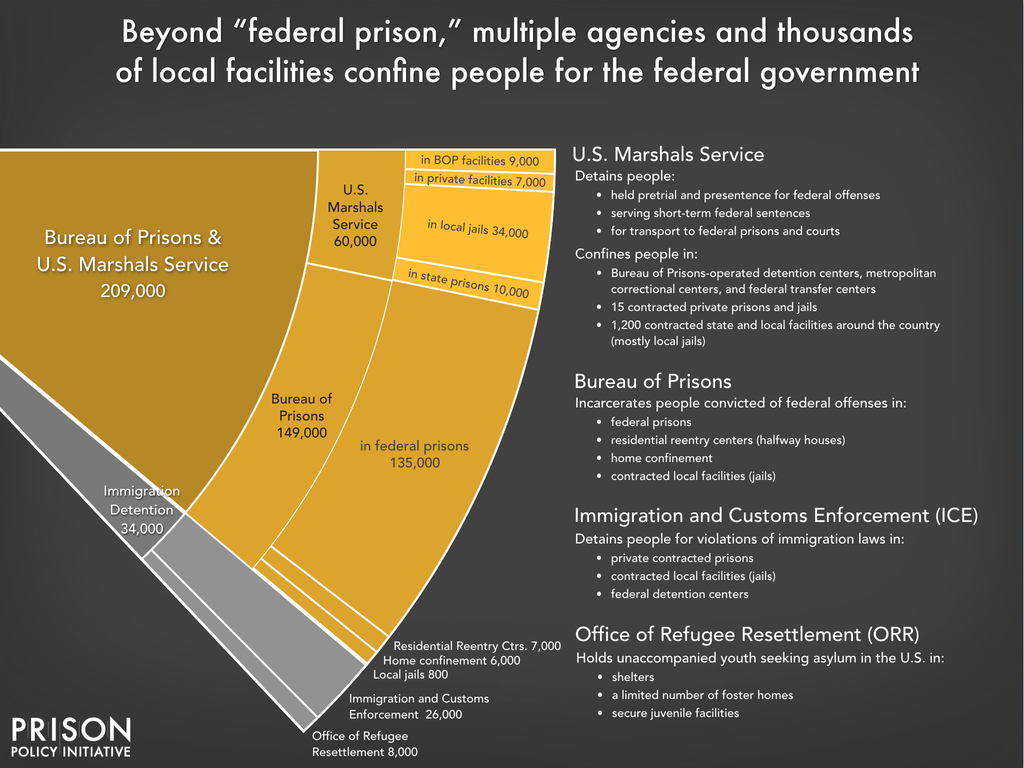

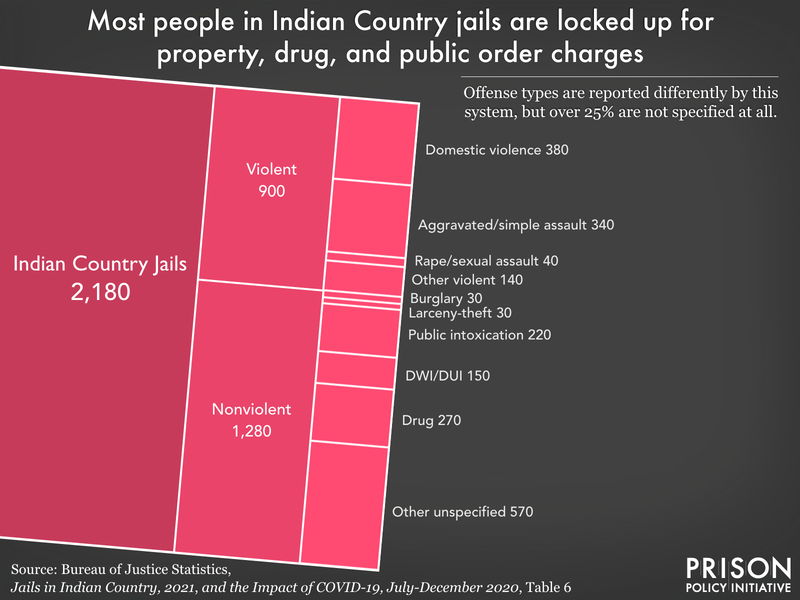

Further complicating matters is the fact that the U.S. doesn’t have one “criminal justice system;” instead, we have thousands of federal, state, local, and tribal systems. Together, these systems hold almost 2 million people in 1,566 state prisons, 98 federal prisons, 3,116 local jails, 1,323 juvenile correctional facilities, 181 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian country jails, as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories. 1

This report offers some much-needed clarity by piecing together the data about this country’s disparate systems of confinement. It provides a detailed look at where and why people are locked up in the U.S., and dispels some modern myths to focus attention on the real drivers of mass incarceration and overlooked issues that call for reform.

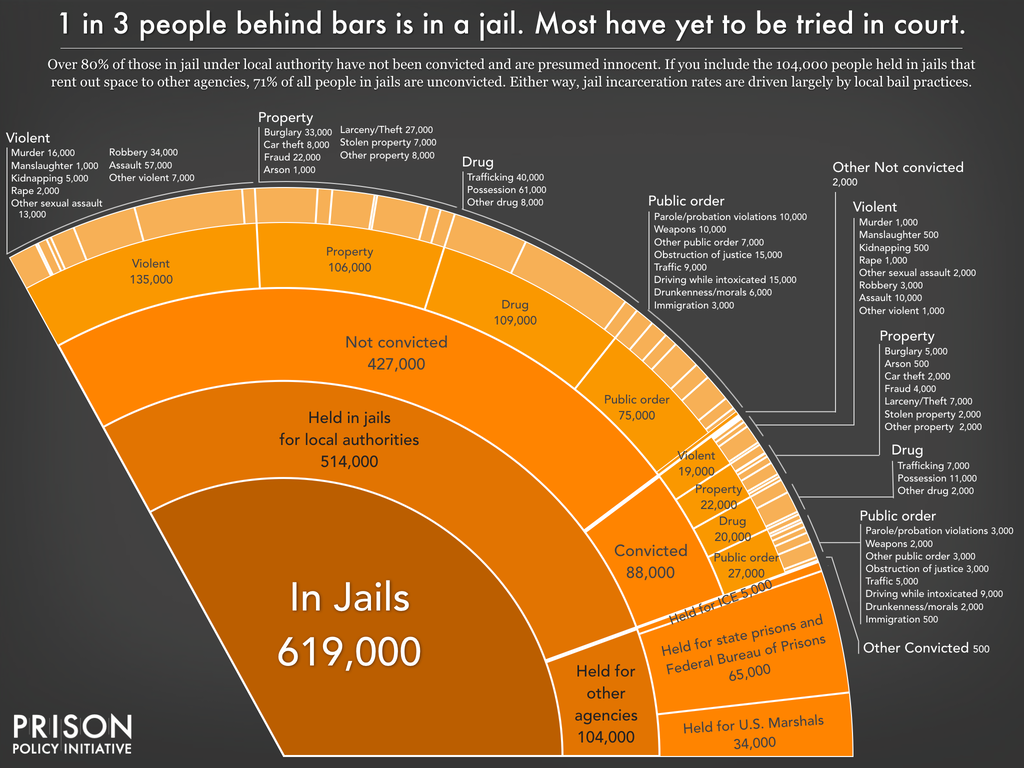

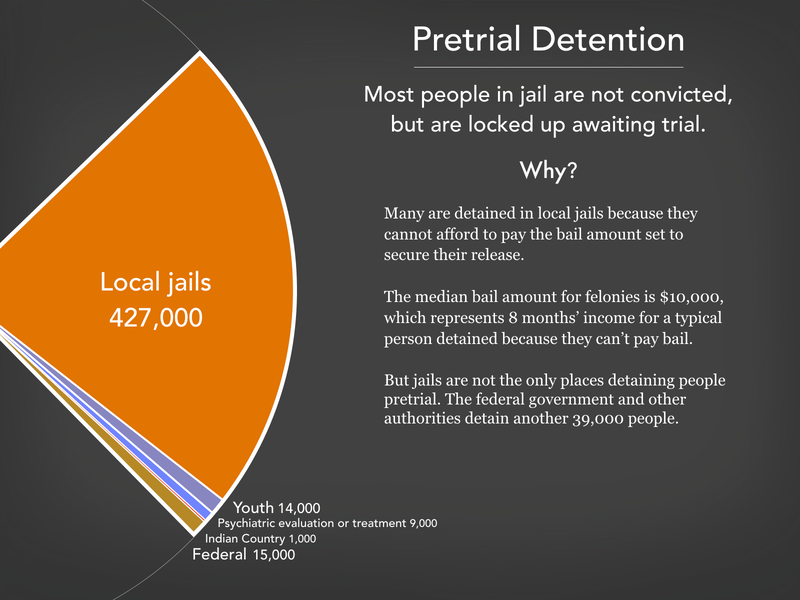

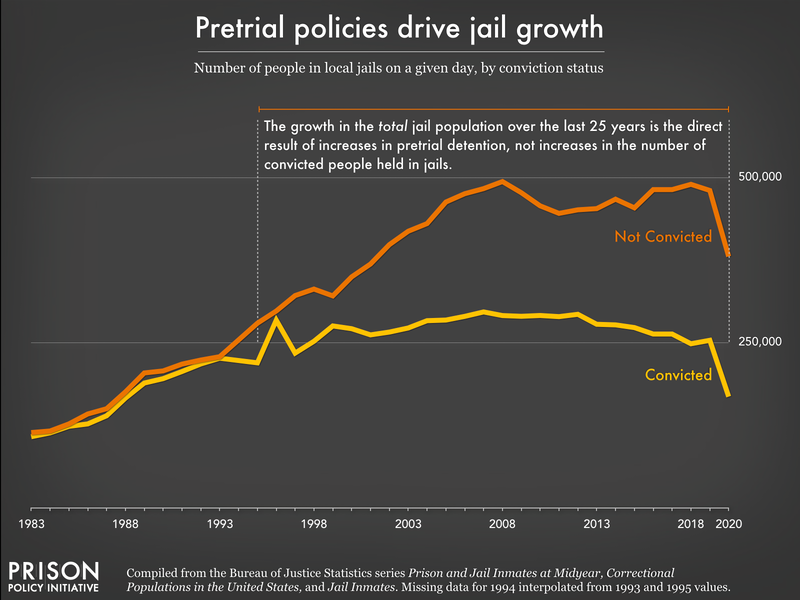

This big-picture view is a lens through which the main drivers of mass incarceration come into focus;4 it allows us to identify important, but often ignored, systems of confinement. The detailed views bring these overlooked systems to light, from immigration detention to civil commitment and youth confinement. In particular, local jails often receive short shrift in larger discussions about criminal justice, but they play a critical role as “incarceration’s front door” and have a far greater impact than the daily population suggests.

While this pie chart provides a comprehensive snapshot of our correctional system, the graphic does not capture the enormous churn in and out of our correctional facilities, nor the far larger universe of people whose lives are affected by the criminal justice system. In 2021, about 421,000 people entered prison gates,5 but people went to jail almost 7 million times.67 Some have just been arrested and will make bail within hours or days, while many others are too poor to make bail and remain behind bars until their trial.8 Only a small number (about 87,500 on any given day) have been convicted, and are generally serving misdemeanors sentences of under a year. At least 1 in 4 people who go to jail will be arrested again within the same year — often those dealing with poverty, mental illness, and substance use disorders, whose problems only worsen with incarceration.

With a sense of the big picture, the next question is: why are so many people locked up? How many are incarcerated for drug offenses? Are the profit motives of private companies driving incarceration? Or is it really about public safety and keeping dangerous people off the streets? There are a plethora of modern myths about incarceration. Most have a kernel of truth, but these myths distract us from focusing on the most important drivers of incarceration.

Nine myths about mass incarceration

The overcriminalization of drug use, the use of private prisons, and low-paid or unpaid prison labor are among the most contentious issues in criminal justice today because they inspire moral outrage. But they do not answer the question of why most people are incarcerated or how we can dramatically — and safely — reduce our use of confinement. Likewise, emotional responses to sexual and violent offenses often derail important conversations about the social, economic, and moral costs of incarceration and lifelong punishment. False notions of what a “violent crime” conviction means about an individual’s dangerousness continue to be used in an attempt to justify long sentences — even though that’s not what victims want. At the same time, misguided beliefs about the “services” provided by jails are used to rationalize the construction of massive new “mental health jails.” Finally, simplistic solutions to reducing incarceration, such as moving people from jails and prisons to community supervision, ignore the fact that “alternatives” to incarceration often lead to incarceration anyway. Focusing on the policy changes that can end mass incarceration, and not just put a dent in it, requires the public to put these issues into perspective.

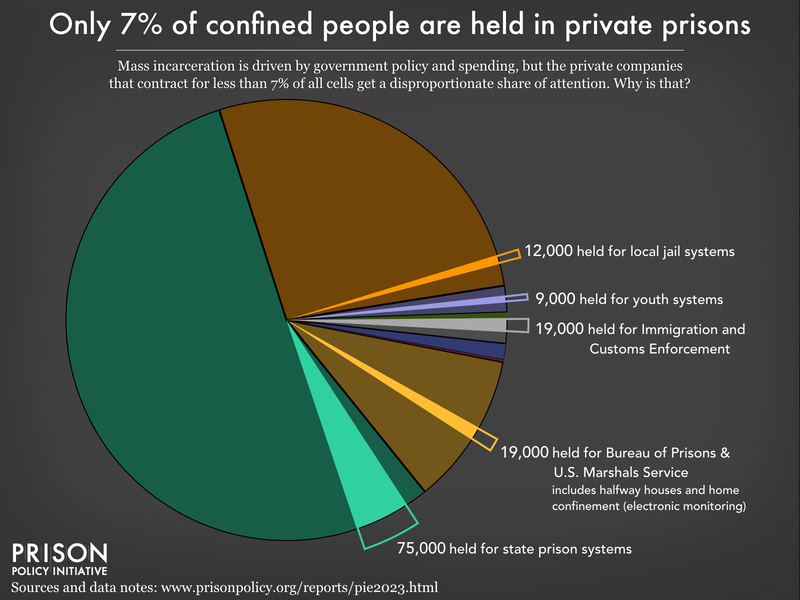

The first myth: Private prisons are the corrupt heart of mass incarceration

In fact, just 7% of all incarcerated people are held in private prisons; the vast majority are in publicly-owned prisons and jails.11 Some states have more people in private prisons than others, of course, and the industry has lobbied to maintain high levels of incarceration, but private prisons are essentially a parasite on the massive publicly-owned system — not the root of it.

Nevertheless, a range of private industries and even some public agencies continue to profit from mass incarceration. Many city and county jails rent space to other agencies, including state prison systems,12 the U.S. Marshals Service, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Private companies are frequently granted contracts to operate prison food and health services (often so bad they result in major lawsuits), and prison and jail telecom and commissary functions have spawned multi-billion dollar private industries. By privatizing services like phone calls, medical care, and commissary, prisons and jails are offloading the costs of incarceration onto incarcerated people and their families, trimming their budgets at an unconscionable social cost.

The second myth: Prisons are “factories behind fences” that exist to provide companies with a huge slave labor force

Simply put, private companies using prison labor are not what stands in the way of ending mass incarceration, nor are they the source of most prison jobs. Only about 5,000 people in prison — less than 1% — are employed by private companies through the federal PIECP program, which requires them to pay at least minimum wage before deductions. (A larger portion work for state-owned “correctional industries,” which pay much less, but this still only represents about 6% of people incarcerated in state prisons.)13

But prisons do rely on the labor of incarcerated people for food service, laundry, and other operations, and they pay incarcerated workers unconscionably low wages: our 2017 study found that on average, incarcerated people earn between 86 cents and $3.45 per day for the most common prison jobs.14 In at least five states, those jobs pay nothing at all. Moreover, work in prison is compulsory, with little regulation or oversight, and incarcerated workers have few rights and protections. If they refuse to work, incarcerated people face disciplinary action. For those who do work, the paltry wages they receive often go right back to the prison, which charges them for basic necessities like medical visits and hygiene items. Forcing people to work for low or no pay and no benefits, while charging them for necessities, allows prisons to shift the costs of incarceration to incarcerated people — hiding the true cost of running prisons from most Americans.

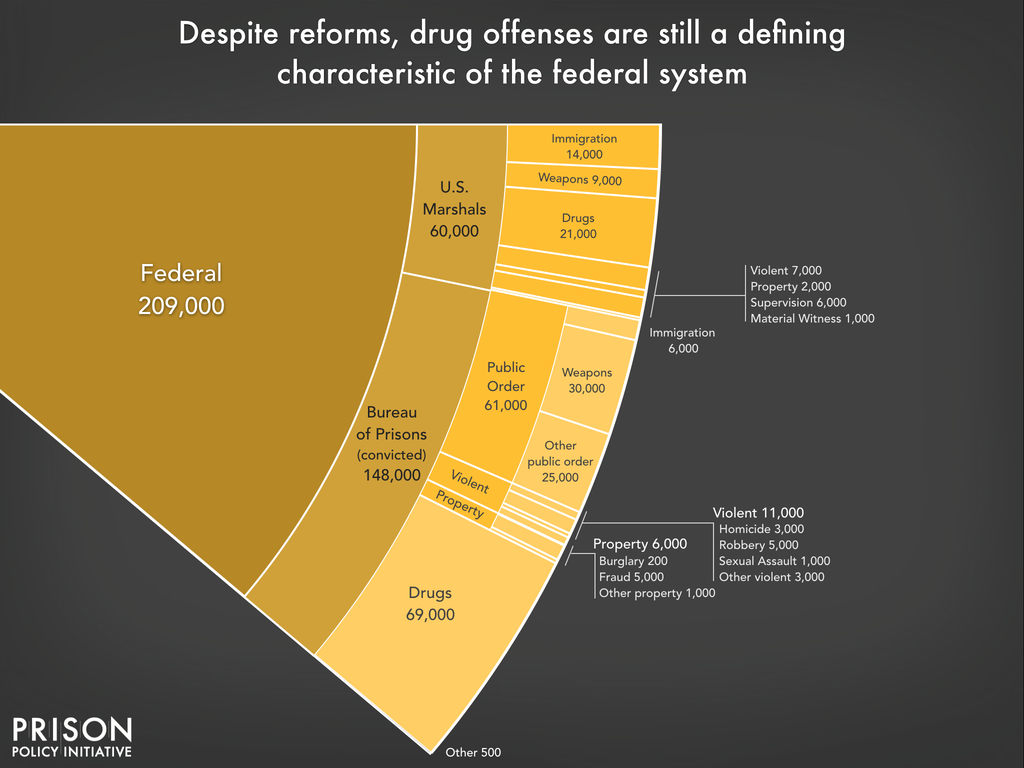

The third myth: Releasing “nonviolent drug offenders” would end mass incarceration

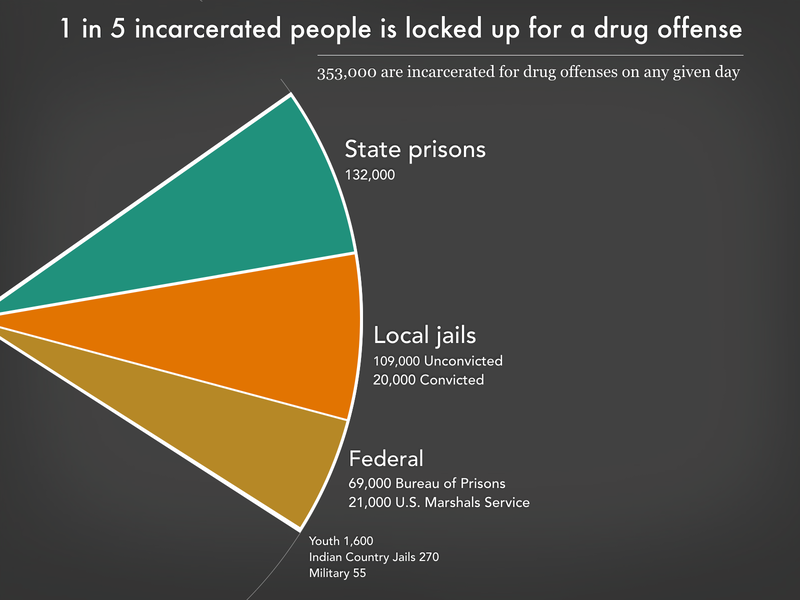

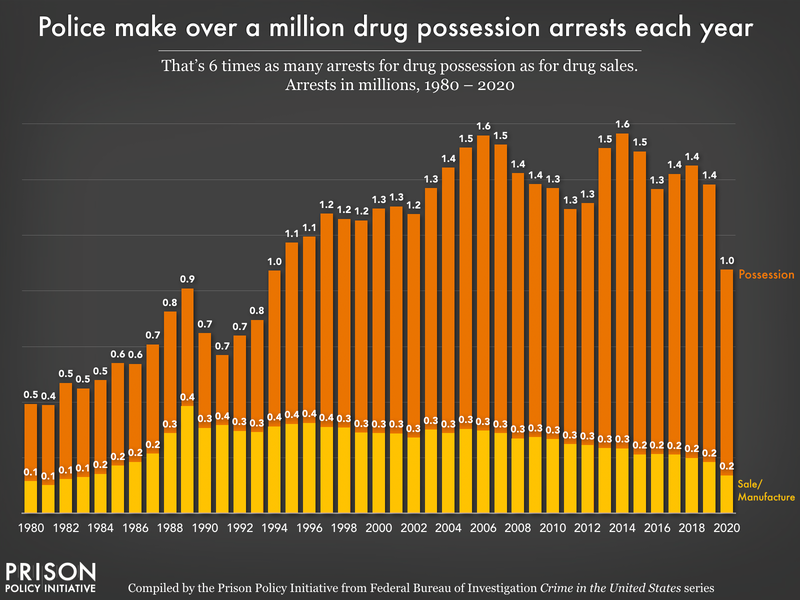

It’s true that police, prosecutors, and judges continue to punish people harshly for nothing more than drug possession. Drug offenses still account for the incarceration of over 350,000 people, and drug convictions remain a defining feature of the federal prison system. And until the pandemic hit (and the official crime data became less reliable), police were still making over 1 million drug possession arrests each year,15 many of which lead to prison sentences. Drug arrests continue to give residents of over-policed communities criminal records, hurting their employment prospects and increasing the likelihood of longer sentences for any future offenses.

Nevertheless, 4 out of 5 people in prison or jail are locked up for something other than a drug offense — either a more serious offense or an even less serious one. To end mass incarceration, we will have to change how our society and our criminal legal system responds to crimes more serious than drug possession. We must also stop incarcerating people for behaviors that are even more benign.

The fourth myth: By definition, “violent crime” involves physical harm

The distinction between “violent” and “nonviolent” crime means less than you might think; in fact, these terms are so widely misused that they are generally unhelpful in a policy context. In the public discourse about crime, people typically use “violent” and “nonviolent” as substitutes for serious versus nonserious criminal acts. That alone is a fallacy, but worse, these terms are also used as coded (often racialized) language to label individuals as inherently dangerous versus non-dangerous.

In reality, state and federal laws apply the term “violent” to a surprisingly wide range of criminal acts — including many that don’t involve any physical harm. In some states, purse-snatching, manufacturing methamphetamines, and stealing drugs are considered violent crimes. Burglary is generally considered a property crime, but an array of state and federal laws classify burglary as a violent crime in certain situations, such as when it occurs at night, in a residence, or with a weapon present. So even if the building was unoccupied, someone convicted of burglary could be punished for a violent crime and end up with a long prison sentence and “violent” record.

The common misunderstanding of what “violent crime” really refers to — a legal distinction that often has little to do with actual or intended harm — is one of the main barriers to meaningful criminal justice reform. Reactionary responses to the idea of violent crime often lead policymakers to categorically exclude from reforms people convicted of legally “violent” crimes. But almost half (47%) of people in prison and jail are there for offenses classified as “violent,” so these carveouts end up gutting the impact of otherwise well-crafted policies. As we and many others have explained before, cutting incarceration rates to anything near international norms will be impossible without changing how we respond to violent crime. To start, we have to be clearer about what that loaded term really means.

The fifth myth: People in prison for violent or sexual crimes are too dangerous to be released

Of course, many people convicted of violent offenses have caused serious harm to others. But how does the criminal legal system determine the risk that they pose to their communities? Again, the answer is too often “we judge them by their offense type,” rather than “we evaluate their individual circumstances.” This reflects the particularly harmful myth that people who commit violent or sexual crimes are incapable of rehabilitation and thus warrant many decades or even a lifetime of punishment.

As lawmakers and the public increasingly agree that past policies have led to unnecessary incarceration, it’s time to consider policy changes that go beyond the low-hanging fruit of “non-non-nons” — people convicted of non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses. Again, if we are serious about ending mass incarceration, we will have to change our responses to more serious and violent crime.

Recidivism data do not support the belief that people who commit violent crimes ought to be locked away for decades for the sake of public safety. People convicted of violent and sexual offenses are actually among the least likely to be rearrested, and those convicted of rape or sexual assault have rearrest rates 20% lower than all other offense categories combined. One reason for the lower rates of recidivism among people convicted of violent offenses: age is one of the main predictors of violence. The risk for violence peaks in adolescence or early adulthood and then declines with age, yet we incarcerate people long after their risk has declined.16

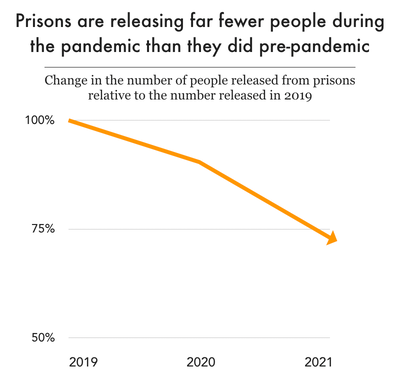

Sadly, most state officials ignored this evidence even as the pandemic made obvious the need to reduce the number of people trapped in prisons and jails, where COVID-19 ran rampant. Instead of considering the release of people based on their age or individual circumstances, most officials categorically refused to consider people convicted of violent or sexual offenses, dramatically reducing the number of people eligible for earlier release.17

The sixth myth: Reforming the criminal legal system leads to more crime

The specter of “rising crime” has re-emerged as a central issue among elected officials, political candidates, and in media commentary, but their explanations and exaggerations of recent crime trends don’t add up. It’s true that while overall crime rates fell, certain types of offenses rose significantly in 2020, and by a much smaller margin in 2021 — especially homicides, shootings, and motor vehicle thefts. As in the past, many in law enforcement and on the right have been quick to blame recent reforms for shifts in crime trends and to resurrect the same “tough on crime” policies that failed in the 80s and 90s. But claims that recent changes in crime were the result of reforms — such as bail reform, changes to police budgets, or electing “progressive” prosecutors — are simply not supported by the evidence. In reality, a number of studies have shown:

- No evidence that progressive prosecutors were to blame for the increase in homicides during the pandemic or in the five years before it.18

- Murder rates were an average of 40% higher in “red” states compared to “blue” states in 2020; more broadly, murder rates over the years 2000-2020 were 23% higher on average in “red” states.

- Releasing people pretrial doesn’t harm public safety. Moreover, the increases in certain types of crime were seen in cities across the country, most of which have not enacted bail reforms.

- Far from being “defunded,” police budgets have increased in the vast majority of cities and counties. And again, cities that increased funding, enacted no bail reforms, and did not elect “progressive” prosecutors also saw increases in homicides in 2020 and 2021.

While the rise in certain serious types of crime is very concerning, the truth is that overall crime rates remain near historic lows. What has actually changed most is the public’s perception of crime, which is driven less by first-hand experience than by the false claims of reform opponents. These false claims are deliberately stoked to undo the hard-won, evidence supported, common sense reforms that have only begun put a dent in mass incarceration.

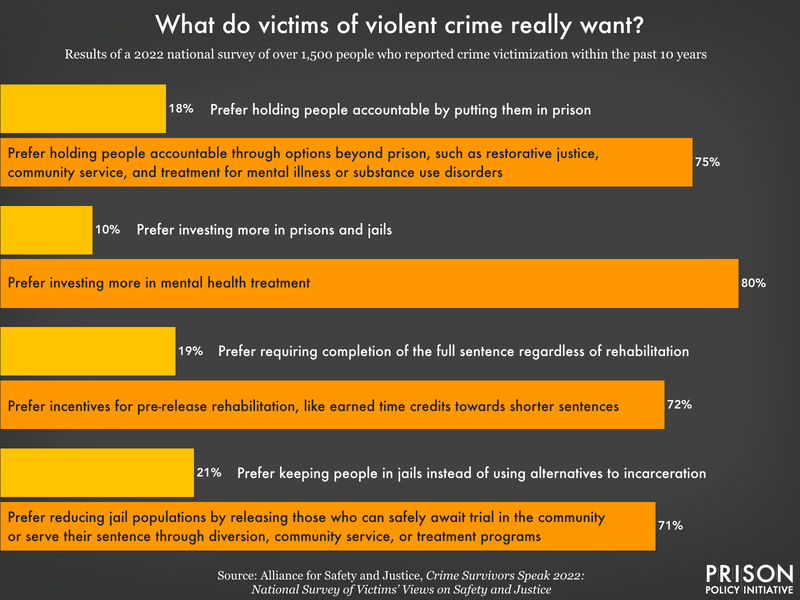

The seventh myth: Crime victims support long prison sentences

Policymakers, judges, and prosecutors often invoke the name of victims to justify long sentences for violent offenses. But contrary to the popular narrative, most victims of violence want violence prevention, not incarceration. Harsh sentences don’t deter violent crime, and many victims believe that incarceration can make people more of a public safety risk. National survey data show that most victims support violence prevention, social investment, and alternatives to incarceration that address the root causes of crime, not more investment in carceral systems that cause more harm.19 This suggests that they care more about the health and safety of their communities than they do about retribution.

Moreover, people convicted of crimes are often victims themselves, complicating the moral argument for harsh punishments as “justice.” While conversations about justice tend to treat perpetrators and victims of crime as two entirely separate groups, people who engage in criminal acts are often victims of violence and trauma, too — a fact behind the adage that “hurt people hurt people.”20 As victims of crime know, breaking this cycle of harm will require greater investments in communities, not the carceral system.

The eighth myth: Some people need to go to jail to get treatment and services

It’s absolutely true that people ensnared in the criminal legal system have a lot of unmet needs. But jails and prisons are no place to recover from a mental health crisis or substance use disorder. Local jails, especially, are filled with people who need medical care and social services, but jails have repeatedly failed to provide these services. For example, while two-thirds of people in local jails have substance use disorders, only a tiny fraction of all jails provide medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder—the gold standard for care. That means that rather than providing drug treatment, jails more often interrupt drug treatment by cutting patients off from their medications. Between 2000 and 2018, the number of people who died of intoxication while in jail increased by almost 400%; typically, these individuals died within just one day of admission.21

Similarly, jails often put people with mental health problems in solitary confinement, provide limited access to counseling, and leave them unmonitored due to constant staffing shortages. The result: suicide is the leading cause of death in local jails, with death rates far exceeding those found in the general U.S. population. Given this track record, the trend of proposing new “mental health jails” to respond to decades of disinvestment in community-based services is particularly alarming. Jails are not safe detox facilities, nor are they capable of providing the therapeutic environment people require for long-term recovery and healing.

Most importantly, jail and prison environments are in many ways harmful to mental and physical health. Decades of research show that many of the defining features of incarceration are stressors linked to negative mental health outcomes: disconnection from family, loss of autonomy, boredom and lack of purpose, and unpredictable surroundings. Inhumane conditions, such as overcrowding, solitary confinement, and experiences of violence also contribute to the lasting psychological effects of incarceration, including the PTSD-like Post-Incarceration Syndrome. As the late Dr. Seymour Halleck observed, “The prison environment is almost diabolically conceived to force the offender to experience the pangs of what many psychiatrists would describe as mental illness.” Even when other options for providing mental health and substance use treatment are scarce, decisionmakers should not rely on correctional settings to do so.

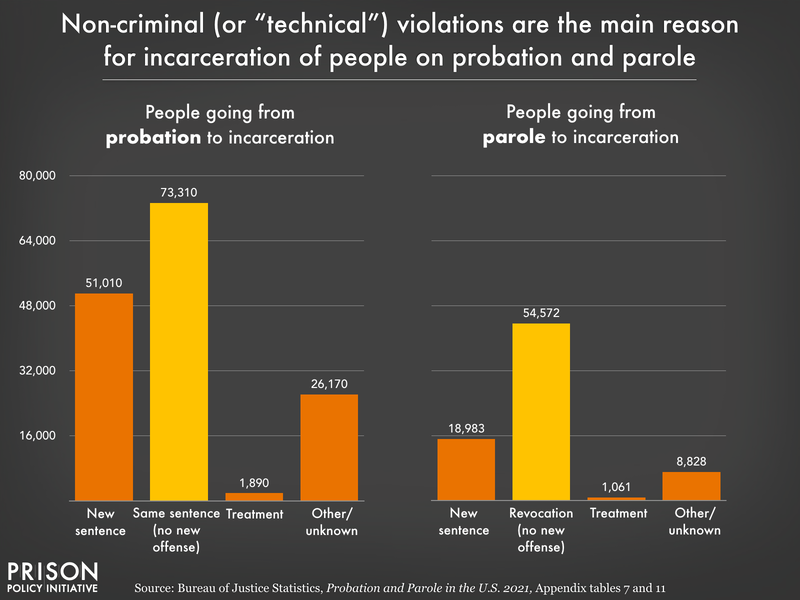

The ninth myth: Expanding community supervision is the best way to reduce incarceration

Community supervision, which includes probation, parole, and pretrial supervision, is often seen as a “lenient” punishment or as an ideal “alternative” to incarceration. But while remaining in the community is certainly preferable to being locked up, the conditions imposed on those under supervision are often so restrictive that they set people up to fail. The long supervision terms, numerous and burdensome requirements, and constant surveillance (especially with electronic monitoring) result in frequent “failures,” often for minor infractions like breaking curfew or failing to pay unaffordable supervision fees.

In 2021, at least 128,000 people were incarcerated for non-criminal violations of probation or parole, often called “technical violations.”2223 These supervision violations accounted for 27% of all admissions to state and federal prisons. Probation, in particular, leads to unnecessary incarceration; until it is reformed to support and reward success rather than detect mistakes, it is not a reliable “alternative.”

The high costs of low-level offenses

Most justice-involved people in the U.S. are not accused of serious crimes; more often, they are charged with misdemeanors or non-criminal violations. Yet even low-level offenses, like technical violations of probation and parole, can lead to incarceration and other serious consequences. Rather than investing in community-driven safety initiatives, cities and counties are still pouring vast amounts of public resources into the processing and punishment of these minor offenses.

Probation & parole violations and “holds” lead to unnecessary incarceration

Often overlooked in discussions about mass incarceration are the various “holds” that keep people behind bars for administrative reasons. A common example is when people on probation or parole are jailed for violating their supervision, either for a new crime or a non-criminal (or “technical”) violation. If a parole or probation officer suspects that someone has violated supervision conditions, they can file a “detainer” (or “hold”), rendering that person ineligible for release on bail. For people struggling to rebuild their lives after conviction or incarceration, returning to jail for a minor infraction can be profoundly destabilizing. The most recent data show that nationally, almost 1 in 5 (19%) people in jail are there for a violation of probation or parole, though in some places these violations or detainers account for over one-third of the jail population. This problem is not limited to local jails, either; in 2019, the Council of State Governments found that nearly 1 in 4 people in state prisons are incarcerated as a result of supervision violations. During the first year of the pandemic, that number dropped only slightly, to 1 in 5 people in state prisons.

Misdemeanors: Minor offenses with major consequences

The “massive misdemeanor system” in the U.S. is another important but overlooked contributor to overcriminalization and mass incarceration. For behaviors as benign as jaywalking or sitting on a sidewalk, an estimated 13 million misdemeanor charges sweep droves of Americans into the criminal justice system each year (and that’s excluding civil violations and speeding). These low-level offenses typically account for about 25% of the daily jail population nationally,24 and much more in some states and counties.

Misdemeanor charges may sound trivial, but they carry serious financial, personal, and social costs, especially for defendants but also for broader society, which finances the processing of these court cases and all of the unnecessary incarceration that comes with them. And then there are the moral costs: People charged with misdemeanors are often not appointed counsel and are pressured to plead guilty and accept a probation sentence to avoid jail time. This means that innocent people routinely plead guilty and are then burdened with the many collateral consequences that come with a criminal record, as well as the heightened risk of future incarceration for probation violations. A misdemeanor system that pressures innocent defendants to plead guilty seriously undermines American principles of justice.

“Low-level fugitives” live in fear of incarceration for missed court dates and unpaid fines

Defendants can end up in jail even if their offense is not punishable with jail time. Why? Because if a defendant fails to appear in court or to pay fines and fees, the judge can issue a “bench warrant” for their arrest, directing law enforcement to jail them in order to bring them to court. While there is currently no national estimate of the number of active bench warrants, their use is widespread and, in some places, incredibly common. In Monroe County, N.Y., for example, over 3,000 people have an active bench warrant at any time, more than 3 times the number of people in the county jails.

But bench warrants are often unnecessary. Most people who miss court are not trying to avoid the law; more often, they forget, are confused by the court process, or have a schedule conflict. Once a bench warrant is issued, however, defendants frequently end up living as “low-level fugitives,” quitting their jobs, becoming transient, and/or avoiding public life (even hospitals) to avoid having to go to jail.

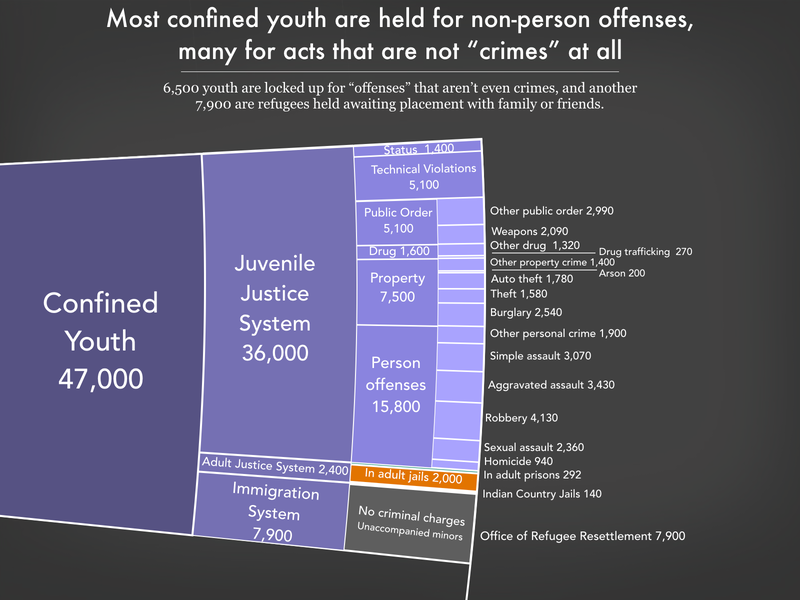

Lessons from the smaller “slices”: Youth, immigration, and involuntary commitment

Looking more closely at incarceration by offense type also exposes some disturbing facts about the 47,000 youth in confinement in the United States: too many are there for a “most serious offense” that is not even a crime. For example, there are over 5,000 youth behind bars for non-criminal violations of their probation rather than for a new offense. An additional 1,400 youth are locked up for “status” offenses, which are “behaviors that are not law violations for adults such as running away, truancy, and incorrigibility.”25 About 1 in 16 youth held for a criminal or delinquent offense is locked in an adult jail or prison, and most of the others are held in juvenile facilities that look and operate a lot like prisons and jails.

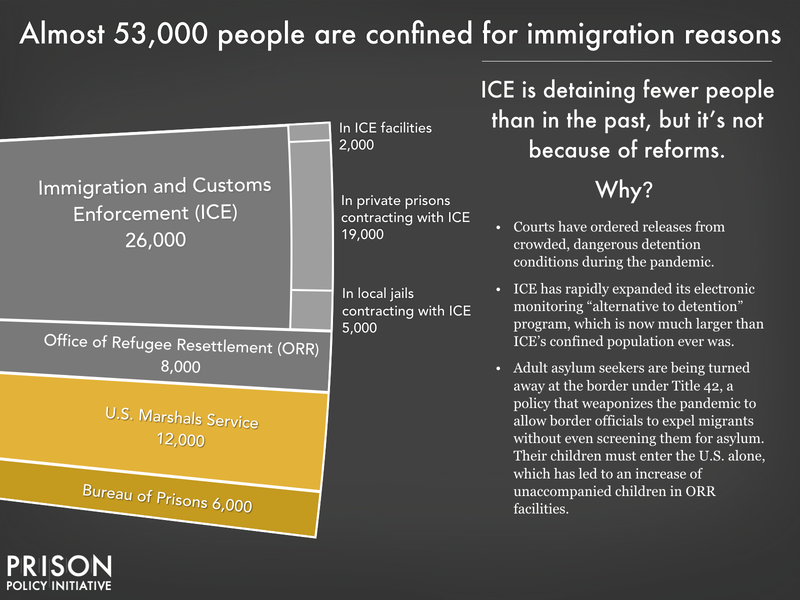

Turning to the people who are locked up criminally and civilly for immigration-related reasons, we find that almost 6,000 people are in federal prisons for criminal convictions of immigration offenses, and 12,400 more are held pretrial by the U.S. Marshals. The vast majority of people incarcerated for criminal immigration offenses are accused of illegal entry or illegal reentry — in other words, for no more serious offense than crossing the border without permission.26

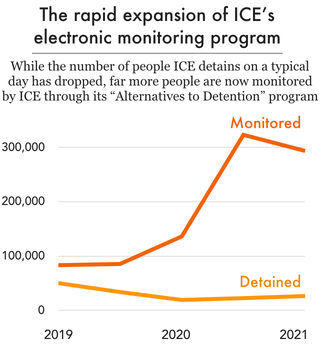

Another 23,300 people are civilly detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) not for any crime, but simply because they are facing deportation.27 ICE detainees are physically confined in federally-run or privately-run immigration detention facilities, or in local jails under contract with ICE. This number is almost half what it was pre-pandemic, but it’s actually climbed back up from a record low of 13,500 people in ICE detention in early 2021. As in the criminal legal system, these pandemic-era trends should not be interpreted as evidence of reforms.28 In fact, ICE is rapidly expanding its overall surveillance and control over the non-criminal migrant population by growing its electronic monitoring-based “alternatives to detention” program.29

An additional 7,900 unaccompanied children are held in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), awaiting placement with parents, family members, or friends. Their number has more than doubled since January of 2020. While these children are not held for any criminal or delinquent offense, most are held in shelters or even juvenile placement facilities under detention-like conditions.30

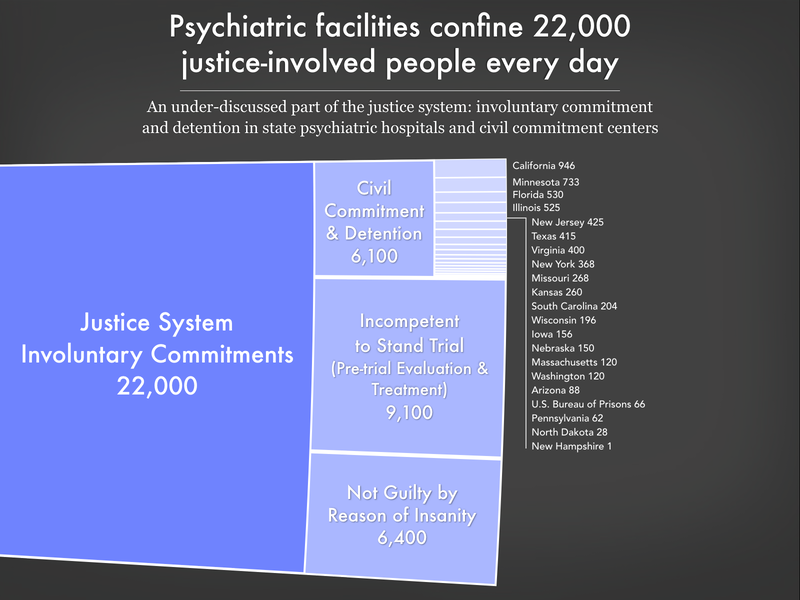

Adding to the universe of people who are confined because of justice system involvement, 22,000 people are involuntarily detained or committed to state psychiatric hospitals and civil commitment centers. Many of these people are not even convicted, and some are held indefinitely. 9,000 are being evaluated pretrial or treated for incompetency to stand trial; 6,000 have been found not guilty by reason of insanity or guilty but mentally ill; another 6,000 are people convicted of sexual crimes who are involuntarily committed or detained after their prison sentences are complete. While these facilities aren’t typically run by departments of correction, they are in reality much like prisons. Meanwhile, at least 38 states allow civil commitment for involuntary treatment for substance use, and in many cases, people are sent to actual prisons and jails, which are inappropriate places for treatment.31

Beyond the “Whole Pie”: Community supervision, poverty, and race and gender disparities

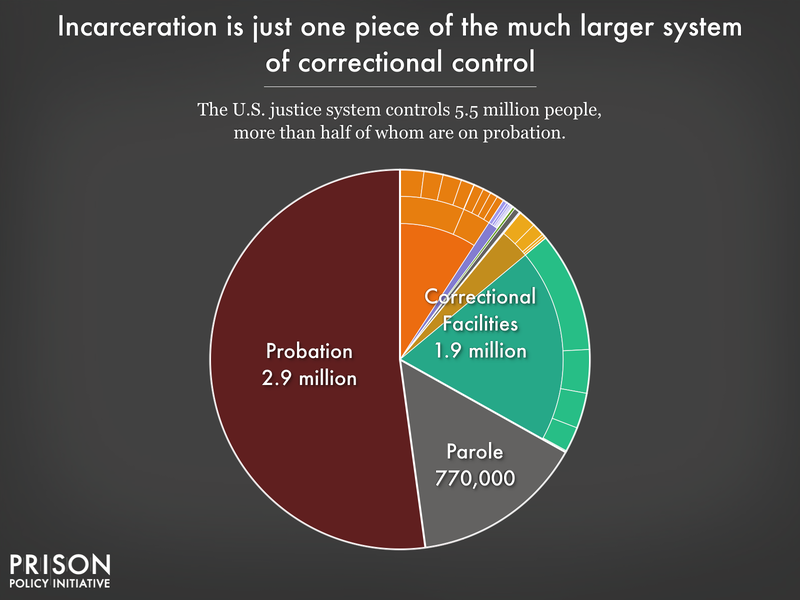

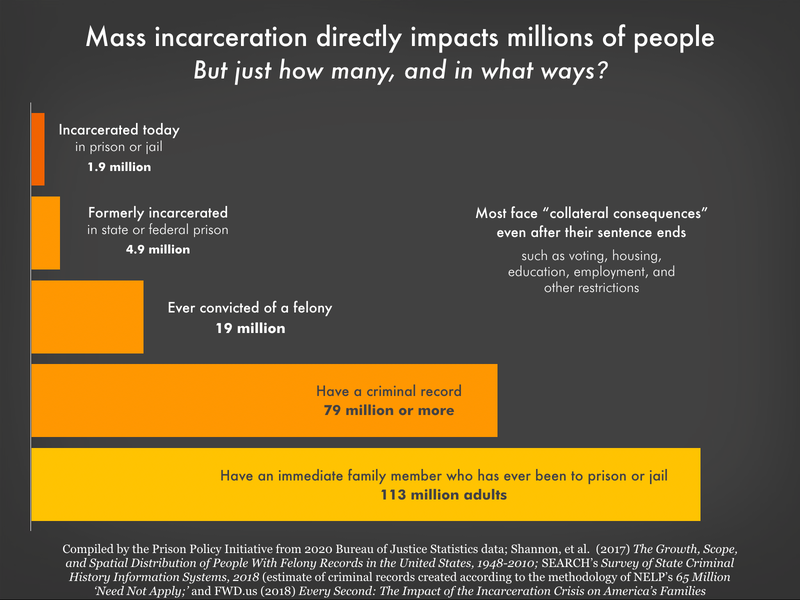

Once we have wrapped our minds around the “whole pie” of mass incarceration, we should zoom out and note that people who are incarcerated are only a fraction of those impacted by the criminal justice system. There are another 803,000 people on parole and a staggering 2.9 million people on probation. Many millions more have completed their sentences but are still living with a criminal record, a stigmatizing label that comes with collateral consequences such as barriers to employment and housing.

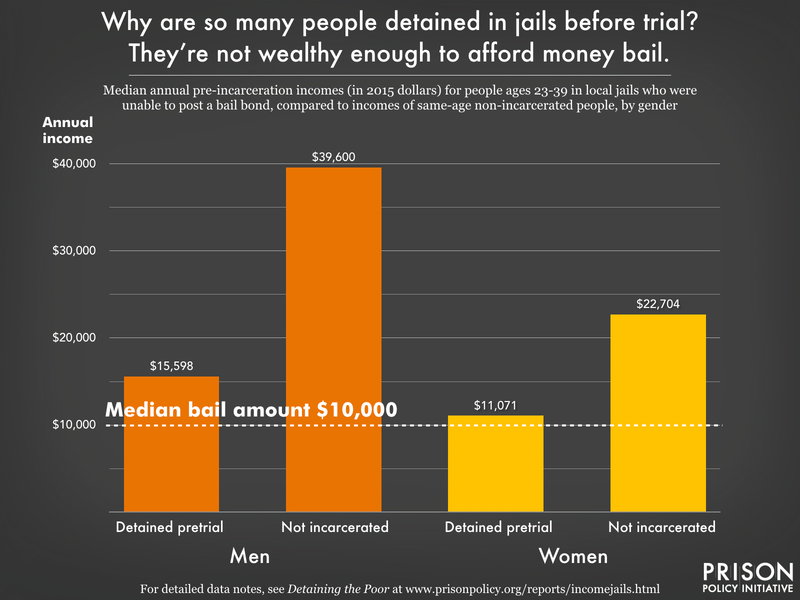

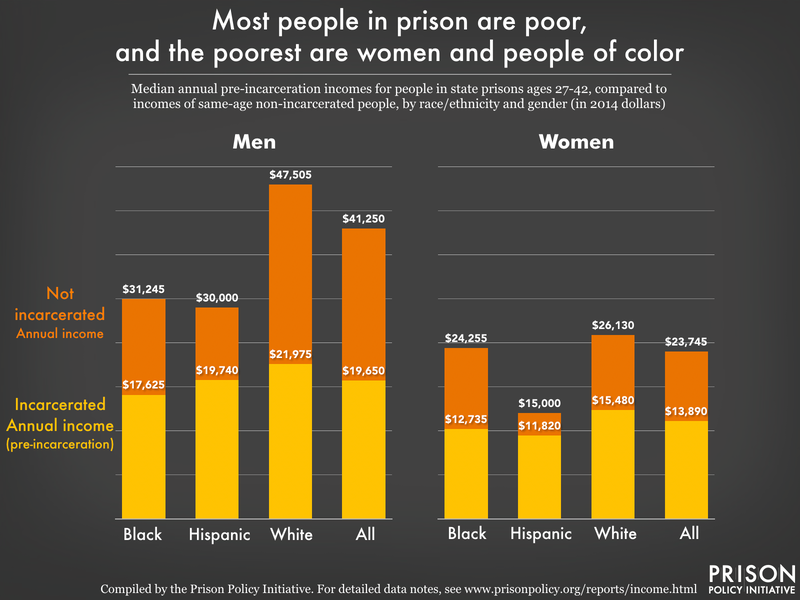

Beyond identifying how many people are impacted by the criminal justice system, we should also focus on who is most impacted and who is left behind by policy change. Poverty, for example, plays a central role in mass incarceration. People in prison and jail are disproportionately poor compared to the overall U.S. population.32 The criminal justice system punishes poverty, beginning with the high price of money bail: The median felony bail bond amount ($10,000) is the equivalent of 8 months’ income for the typical detained defendant. As a result, people with low incomes are more likely to face the harms of pretrial detention. Poverty is not only a predictor of incarceration; it is also frequently the outcome, as a criminal record and time spent in prison destroys wealth, creates debt, and decimates job opportunities.33

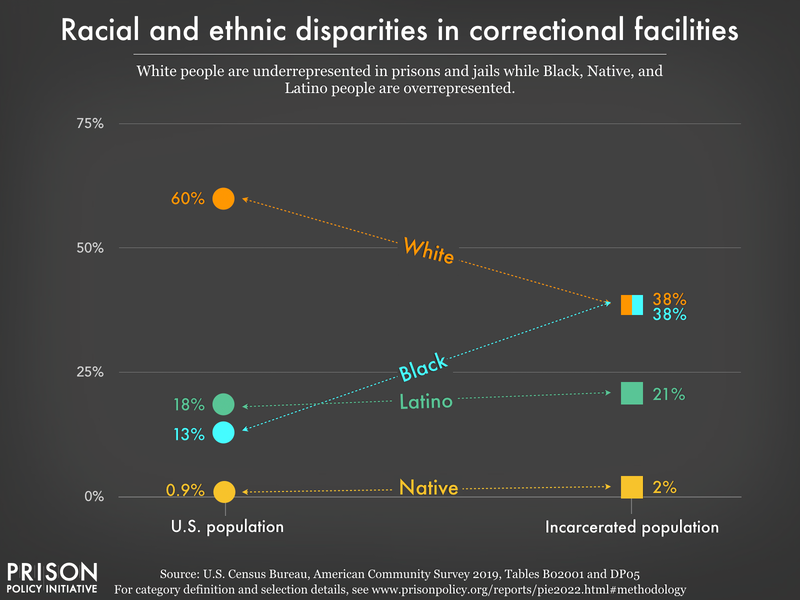

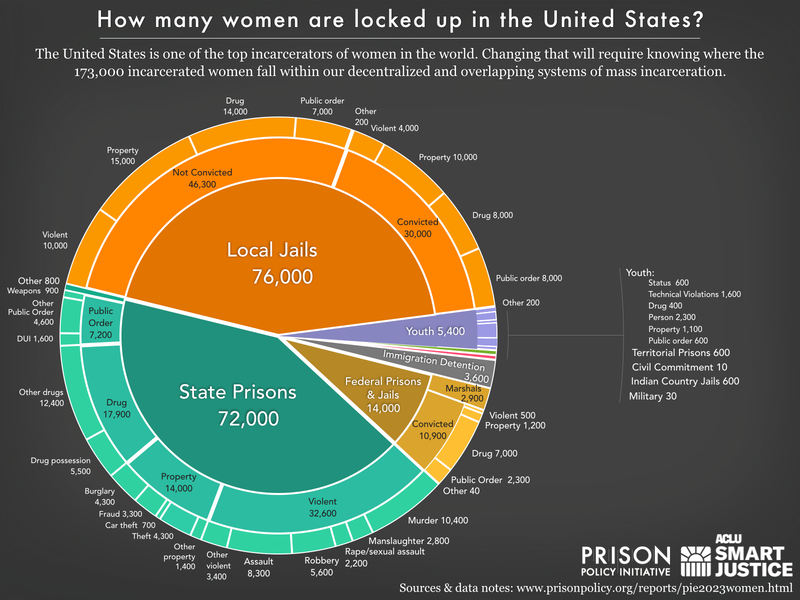

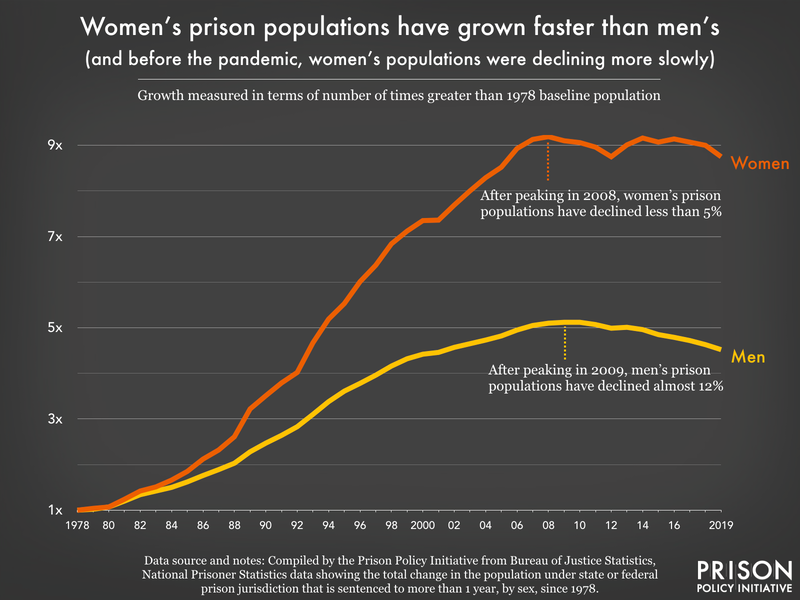

It’s no surprise that people of color — who face much greater rates of poverty — are dramatically overrepresented in the nation’s prisons and jails. These racial disparities are particularly stark for Black Americans, who make up 38% of the incarcerated population despite representing only 12% of U.S residents. The same is true for women, whose incarceration rates have for decades risen faster than men’s, and who are often behind bars because of financial obstacles such as an inability to pay bail. As policymakers continue to push for reforms that reduce incarceration, they should avoid changes that will widen disparities, as has happened with juvenile confinement and with women in state prisons.

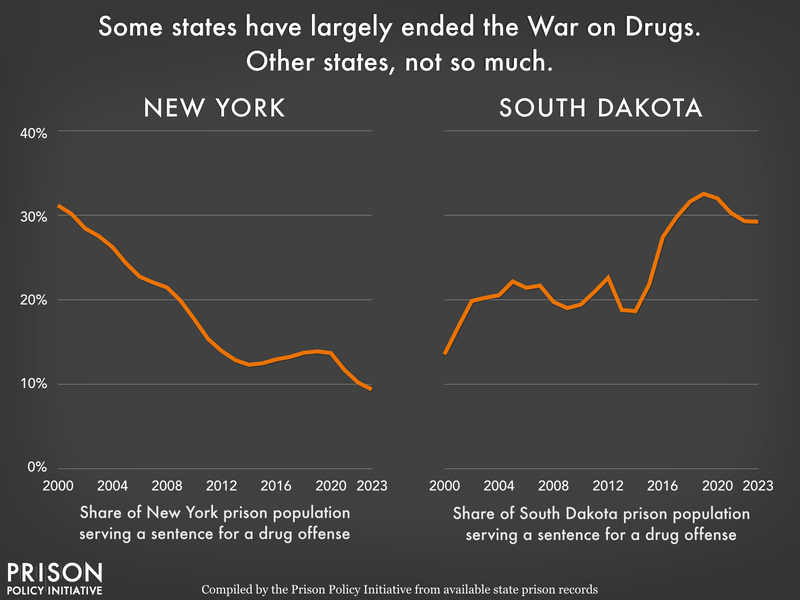

Equipped with the full picture of how many people are locked up in the United States, where, and why, we all have a better foundation for moving the conversation about criminal legal system reform forward. For example, the data makes it clear that ending the war on drugs will not alone end mass incarceration, though the federal government and some states have taken an important step by reducing the number of people incarcerated for drug offenses. Looking at the “whole pie” of mass incarceration opens up conversations about where it makes sense to focus our energies at the local, state, and national levels. For example:

- How can we effectively invest in communities to make it less likely that someone comes into contact with the criminal legal system in the first place? And what measures can help aid successful reentry and end the vicious cycle of re-incarceration that so many individuals and families experience?

- Can we persuade government officials and prosecutors to revisit the reflexive, simplistic policymaking that has served to increase incarceration for “violent” offenses? How can we eliminate policy “carveouts” that exclude broad categories of people from reforms and end up gutting the impact of reforms?

- What will it take to embolden policymakers and the public to do what it takes to shrink the second largest slice of the pie — the thousands of local jails? And what will it take to redirect public spending to smarter investments like community-based drug treatment and job training?

- While the federal prison system is a small slice of the total pie, how can improved federal policies and financial incentives be used to advance state and county level reforms? And for their part, how can elected sheriffs, district attorneys, and judges — who all control larger shares of the correctional pie — slow the flow of people into the criminal legal system?

- Given that the companies with the greatest impact on incarcerated people are not private prison operators, but service providers that contract with public facilities, how can governments end contracts that squeeze money from those behind bars and their families?

- What reforms can we implement to both reduce the number of people incarcerated in the U.S. and the well-known racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal legal system?

- What lessons can we learn from the pandemic? Are federal, state, and local governments prepared to respond to future pandemics, epidemics, natural disasters, and other emergencies, including with plans to decarcerate? And how can states and the federal government better utilize compassionate release and clemency powers moving forward?

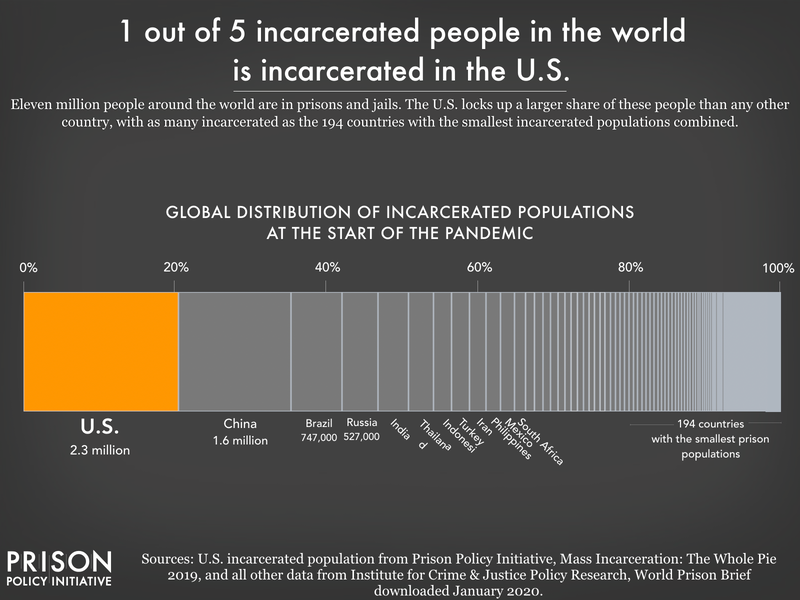

The United States has the dubious distinction of having the highest incarceration rate in the world. Looking at the big picture of the 1.9 million people locked up in the United States on any given day, we can see that something needs to change. Both policymakers and the public have the responsibility to carefully consider each individual slice of the carceral “pie” and ask whether legitimate social goals are served by putting each group behind bars, and whether any benefit really outweighs the social and fiscal costs.

Even narrow policy changes, like reforms to bail, can meaningfully reduce our society’s use of incarceration. At the same time, we should be wary of proposed reforms that seem promising but will have only minimal effect, because they simply transfer people from one slice of the correctional “pie” to another or needlessly exclude broad swaths of people. Keeping the big picture in mind is critical if we hope to develop strategies that actually shrink the “whole pie.”

Get our latest data & analysis in your inbox!

Data sources & methodology

This section covers a lot of ground, from why we attempt to piece together the data ourselves in the first place to where we source the data and how we adjust it to make the various pieces fit together. Read on to learn:

- Why we — and not the government — compile the data ⤵

- Which data sources we relied on for state and federal prisons and local jail populations ⤵

- Which data sources we used for the smaller slices of the “pie”: youth, immigration, involuntary commitments, U.S. territories, Indian Country jails, and the military ⤵

- How we calculated the broader “pie” of correctional control, including probation and parole systems ⤵

- How we determined the number of private facilities ⤵

- How we adjusted the data to make sure people were only counted once ⤵

- What data we used to make our racial disparities graph — and why ⤵

People new to criminal justice issues might reasonably expect that a big picture analysis like this would be produced not by advocates, but by the criminal legal system itself. The unfortunate reality is that there isn’t one centralized criminal legal system to do such an analysis. Instead, even thinking just about adult corrections, we have a federal system, 50 state systems, 3,000+ county systems, 25,000+ municipal systems, and so on. Each of these systems collects data for its own purposes that may or may not be compatible with data from other systems and that might duplicate or omit people counted by other systems.

This isn’t to discount the work of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which, despite limited resources, undertakes the Herculean task of organizing and standardizing the data on correctional facilities. And it’s not to say that the FBI doesn’t work hard to aggregate and standardize police arrest and crime report data. But the fact is that the local, state, and federal agencies that carry out the work of the criminal justice system — and are the sources of BJS and FBI data — weren’t set up to answer many of the simple-sounding questions about the “system.”

Similarly, there are systems involved in the confinement of system-involved people that might not consider themselves part of the criminal legal system, but should be included in a holistic view of incarceration. Juvenile justice, civil detention and commitment, immigration detention, and commitment to psychiatric hospitals for criminal justice involvement are examples of this broader universe of confinement that is often ignored. The “whole pie” incorporates data from these systems to provide the most comprehensive view of incarceration possible.

To produce this report, we took the most recent data available for each part of these systems, and, where necessary, adjusted the data to ensure that each person was only counted once, only once, and in the right place. ⤴

Data sources

This briefing uses the most recent data available on the number of people in various types of facilities and the most significant charge or conviction. Because the various systems of confinement collect and report data on different schedules, this report reflects population data collected between 2019 and 2023 (and some of the data for people in psychiatric facilities dates back to 2014). Furthermore, because not all types of data are updated each year, we sometimes had to calculate estimates; for example, we applied the percentage distribution of offense types from the previous year to the current year’s total count data. For this reason, we chose to round most labels in the graphics to the nearest thousand, except where rounding to the nearest ten, nearest one hundred, or the nearest 500 was more informative given the context. This rounding process may also result in some parts not adding up precisely to the total.

Our data sources were:

- State prisons: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 1 provides the total population as of December 31, 2021, and Table 16 provides data (as of December 31, 2020) that can be used to calculate the ratio of different offense types.

- Jails: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 1 and Table 5, reporting average daily population and convicted status for midyear 2021, and our analysis of the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 2002.34

- Federal:

- Bureau of Prisons: : Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Population Statistics, reporting data as of March 3, 2023 (total population of 157,930), and Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 19, reporting data as of September 30, 2021 (we applied the percentage distribution of offense types from that table to the 2023 BOP population).

- U.S. Marshals Service provided its most recent estimated population count (60,439) in a February 2023 response to our FOIA request, reporting the projected average daily population for fiscal year 2023.

The same response also provided a more detailed breakdown of this population by facility and offense type. The numbers of people held in federal detention centers (9,445), in directly-contracted private facilities (6,731), in non-paid facilities (17), and in all state, local, and indirectly-contracted (“pass thru”) facilities with Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGAs) combined (44,246) came from the FOIA response. To determine how many people held in facilities with IGAs were held in local jails specifically (33,900, which includes an unknown portion of indirectly-contracted “pass thru” jails), we turned to Table 8 Jail Inmates in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 8, reporting data as of June 30, 2021. The remainder of those in IGAs (10,346) were held in state facilities and other indirectly-contracted (“pass thru”) facilities (most of which are private), but the available data make it impossible to disaggregate those two groups.

We created our own estimated offense breakdown by applying the ratios of reported offense types (excluding the vague “other new offense” and “writs, holds & transfers” categories”) to the total average daily population in 2023. (For those interested in the raw data including those categories, see page 9 of the 2023 FOIA response.) ⤴

- Youth: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (EZACJRP), reporting total population and facility data for October 23, 2019. (A more recent number of youth in residential placement in 2020 — 25,014 — was published in the Juvenile Residential Facility Census Databook, but we opted to use the 2019 data because of potential reporting issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, noted in the Databook.) Our data on youth incarcerated in adult prisons comes from Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 15, reporting data for December 31, 2021, and youth in adult jails from Jail Inmates in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 2, reporting data for the last weekday in June 2021. The number of youth reported in Indian Country facilities comes from the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Jails in Indian Country, 2021, and the Impact of COVID-19, July-December 2020 Table 6, also reporting data for the last weekday in June, 2021. For more information on the geography of the juvenile system, see the No Kids in Prison campaign.

- Immigration detention: The average daily population of 26,47735 in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention comes from ICE’s FY 2023 ICE Statistics spreadsheet as of February 21, 2023. The count of 7,565 youth in Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) custody comes from the Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC) Program Fact Sheet, reporting the population as of January 27, 2023. Our estimates of how many ICE detainees are held in federal, private, and local facilities come from our analysis of the same ICE FY 2023 ICE Statistics Spreadsheet. 9% were in federal ICE/BOP facilities (which we defined as Service Processing Centers, Staging facilities, and BOP detention centers); 72% in private contract facilities (including Contract Detention Facilities for ICE and U.S. Marshals Service and Dedicated Intergovernmental Service Agreements); and 19% in city and county-operated jails (including Intergovernmental Service Agreements for ICE and U.S. Marshals Service).

- Criminal legal system-related involuntary commitment:

- State psychiatric hospitals (people committed to state psychiatric hospitals by courts after being found “not guilty by reason of insanity” (NGRI) or, in some states, “guilty but mentally ill” (GBMI) and others held for pretrial evaluation or for treatment as “incompetent to stand trial” (IST)): These counts are from pages 92, 99, and 104 of the August 2017 NRI report, Forensic Patients in State Psychiatric Hospitals: 1999-2016, reporting data from 37 states for 2014. The categories NGRI and GBMI are combined in this data set, and for pretrial, we chose to combine pretrial evaluation and those receiving services to restore competency for trial, because in most cases, these indicate people who have not yet been convicted or sentenced. This is not a complete view of all justice-related involuntary commitments, but we believe these categories and these facilities capture the largest share. We are not aware of any alternative data source with newer data.

- Civil detention and commitment: (At least 20 states and the federal government operate facilities for the purposes of detaining people convicted of sexual crimes after their sentences are complete. These facilities and the confinement there are technically civil, but in reality are quite like prisons. People under civil commitment are held in custody continuously from the time they start serving their sentence at a correctional facility through their confinement in the civil facility.) The civil commitment counts come from an annual survey conducted by the Sex Offender Civil Commitment Programs Network shared by SOCCPN President Shan Jumper. Counts for most states are from the 2022 survey, but for states that did not participate in 2022, we included the most recent figures available: Nebraska’s count is as of 2018, New Hampshire’s count is from 2020, South Carolina’s is from 2021, and the federal Bureau of Prisons’ count is from 2017.

- Territorial prisons (correctional facilities in the U.S. Territories of American Samoa, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, and U.S. Commonwealths of the Northern Mariana Islands and Puerto Rico): Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 25, reporting data for December 31, 2021.

- Indian country jails (correctional facilities operated by tribal authorities or the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs): Jails in Indian Country, 2021, and the Impact of COVID-19, July-December 2020 Table 1, reporting the population as of the last weekday in June, 2021.

- Military: Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables Tables 23 (for total population) and 24 (for offense types) reporting data as of December 31, 2021. ⤴

- Probation and parole: Our counts of the number of people on probation and parole are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Correctional Populations in the United States, 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 1, reporting data for December 31, 2021. We adjusted these totals to ensure that people with multiple statuses (e.g., people on probation who were also held in jails) were counted only once in their most restrictive category, using published data on people with dual statuses in Table 11 of the same report. For readers interested in knowing the total number of people on parole and probation, ignoring any double-counting with other forms of correctional control, there were 803,200 people on parole and 2,963,000 people on probation as of December 31, 2021. ⤴

- Private facilities: Except for local jails (which we will explain in the “Adjustments to avoid double counting” section below), our identification of the number of people held in private facilities was as follows:

- For state prisons, the number of people in private prisons came from Table 14 in Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables.

- For the Federal Bureau of Prisons, we calculated the percentage of the total BOP population (8.1%) that were held in Residential Reentry Centers (halfway houses) or in home confinement as of March 3, 2023, according to the Bureau of Prisons “Population Statistics.” We then applied that percentage to our total convicted BOP population (removing the 9,445 people held in 12 BOP detention centers being held for the U.S. Marshals Service) to estimate the number of people serving a sentence in a privately-operated setting for the BOP. We chose this method instead of using the number published in Table 14 of Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables because as of 2023, the BOP no longer places sentenced people in private prisons. The inclusion of Residential Reentry Centers and home confinement in our definition of “private” facilities is consistent with the definition used by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in Table 14 of Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables.

- For the U.S. Marshals Service, we used the 2023 FOIA response reporting the projected average daily population for fiscal year 2023 as of February 12, 2023, including only those held in “private” (directly contracted) facilities. However, we note that an unknown portion of the 14,752 people held in indirectly-contracted (“pass thru”) facilities with Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGAs) are also held in private facilities; the available data make it impossible to disaggregate these “pass thru” facilities according to status as private or public. (This marks a change in how we counted people held for the Marshals Service in private facilities compared to the 2022 version of this report, which assumed that all “pass thru” facilities were private.)

- For youth, we used the 2019 Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement, which provides a breakdown of the number of youth held in publicly and privately operated facilities.

- For immigration detention, we used the Facility Information provided in ICE’s FY 2023 ICE Statistics spreadsheet to calculate the number of people detained in facilities categorized as “CDF” (Contract Detention Facilities), “USMS CDF” (Contract Detention Facilities contracted by the U.S. Marshals Service), and “DIGSA” (privately owned and/or operated facilities contracted through Dedicated Intergovernmental Service Agreements for ICE use). ⤴

Adjustments to avoid double counting

To avoid counting anyone twice, we performed the following adjustments:

- To avoid anyone in immigration detention being counted twice, we removed the 19% (5,017) of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detained population that is held in local jails under Intergovernmental Service Agreement contracts (IGSAs) from the total jail population. We removed 26.9% of these ICE detainees from the jail convicted population and the balance from the unconvicted population. We based these percentages on the breakdown by criminal status of the ICE “currently detained” population as of February 26, 2023 in the ICE Detention Statistics spreadsheet, counting “convicted criminal” as convicted and “pending criminal charges” and “other immigration violator” as unconvicted.

- To avoid anyone in local jails on behalf of state or federal prison authorities from being counted twice, we removed the 65,399 people — cited in Table 14 of Prisoners in 2021 — Statistical Tables — confined in local jails on behalf of federal or state prison systems from the total jail population and from the numbers we calculated for those in local jails that are convicted. To avoid those being held by the U.S. Marshals Service from being counted twice, we removed from the jail total 33,900 Marshals detainees reported as held in local jails in Jail Inmates in 2021 — Statistical Tables Table 8. We removed 75.9% of these people held in jails for the Marshals Service from the jail convicted population, and the balance from the unconvicted jail population. We based these percentages on our analysis of the Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002. We are not aware of any more recent source breaking down the U.S. Marshals Service detained population by conviction status.

- Because we removed ICE detainees and people under the jurisdiction of federal and state authorities from the jail population, we had to recalculate the offense distribution reported in Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002 who were “convicted” or “not convicted,” excluding the people who reported that they were being held on behalf of state authorities, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the U.S. Marshals Service, or U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).36 Our definition of “convicted” was those who reported that they were “To serve a sentence in this jail,” “To await sentencing for an offense,” or “To await transfer to serve a sentence somewhere else.” Our definition of “not convicted” was “To stand trial for an offense,” “To await arraignment,” or “To await a hearing for revocation of probation/parole or community release.”

- For our analysis of people held in private jails for local authorities, we applied the percentage of the total custody population held in private facilities in midyear 2019 (calculated from Table 20 of Census of Jails, 2005-2019) to our count of people held in jails for local authorities (514,284) in 2021, after making the adjustments described in this section. ⤴

Our graph of the racial and ethnic disparities in correctional facilities (as shown in Slideshow 6) uses the only data source that has data for all types of adult correctional facilities: the U.S. Census. Because the relevant tables from the 2020 decennial Census have not been published yet, we used the 2019 American Community Survey tables B02001and DP05 and represented the four named racial and ethnic groups that account for at least 2%, nationally, of the population in correctional facilities. Not included on the graphic are Asian people, who make up 1% of the correctional population, Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, who make up 0.3%, people identifying as “Some other race,” who account for 6.3%, and those of “Two or more races,” who make up 4% of the total national correctional population.

Note that because Latinos may be of any race and because of how the Census Bureau published race and ethnicity data in the relevant table, we used the Census data for “White alone, Not Hispanic or Latino” for white people, but the Census Bureau’s data for “Black or African American” and “American Indian and Alaska Native” people may include people who identify as both that race and Latino. ⤴

How to link to specific images and sections

To help readers link to specific images in this report, we created these special urls:

- How many people are locked up in the United States?

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow1/1

- 1 in 3 people behind bars is in a jail. Most have yet to be tried in court.

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow1/2

- Despite reforms, drug offenses are still a defining characteristic of the federal system

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow1/3

- Beyond “federal prison,” multiple agencies and thousands of local facilities confine people for the federal government

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow1/4

- Prisons are releasing far fewer people during the pandemic than they did pre-pandemic

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#covid

- Pretrial Detention

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow2/1

- Pretrial policies drive jail growth

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow2/2

- Why are so many people detained in jails before trial? They’re not wealthy enough to afford money bail.

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow2/3

- Only 7% of confined people are held in private prisons

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#private_facilities

- 1 in 5 incarcerated people is locked up for a drug offense

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow3/1

- Police make over a million drug possession arrests each year

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow3/2

- Some states have largely ended the War on Drugs. Other states, not so much.

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow3/3

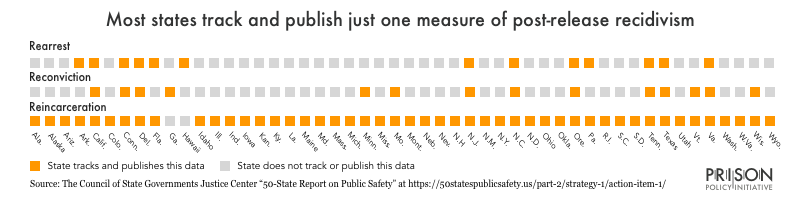

- Most states track and publish just one measure of post-release recidivism

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#releaserecidivism

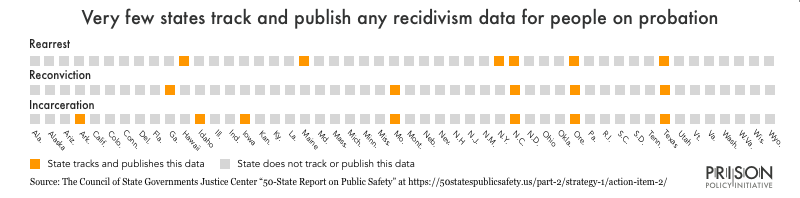

- Very few states track and publish any recidivism data for people on probation

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#probationrecidivism

- What do victims of violent crimes really want?

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#victimswant

- Non-criminal (or “technical”) violations are the main reason for incarceration of people on probation and parole

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow4/1

- Contrary to myth, people incarcerated for violent offenses and released are least likely to be arrested again

- /reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow4/1

- Most confined youth are held for non-person offenses, many for acts that are not “crimes” at all

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow5/1

- Almost 53,000 people are confined for immigration reasons

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow5/2

- Psychiatric facilities confine 22,000 justice-involved people every day

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow5/3

- Most people in Indian Country jails are locked up for property, drug, and public order charges

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow5/4

- The rapid expansion of ICE’s electronic monitoring program

- /reports/pie2023.html#iceexpansion

- Mass incarceration directly impacts millions of people: But just how many, and in what ways?

- /reports/pie2023.html#impacted

- Incarceration is just one piece of the much larger system of correctional control

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow6/1

- Racial and ethnic disparities in correctional facilities

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow6/2

- How many women are locked up in the United States?

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow6/3

- Women’s prison populations have grown faster than men’s (and before the pandemic, women’s populations were declining more slowly)

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow6/4

- Most people in prison are poor, and the poorest are women and people of color

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow6/5

- 1 out of 5 incarcerated people in the world is incarcerated in the U.S.

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#slideshows/slideshow6/6

To help readers link to specific report sections or paragraphs, we created these special urls:

- What actually happened to prison and jail populations during the pandemic?

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#covid

- Jails vs. prisons: What’s the difference?

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#jailsvprisons

- Nine myths about mass incarceration

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#myths

- Offense categories might not mean what you think

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#offensecategories

- The first myth: Private prisons are the corrupt heart of mass incarceration

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#firstmyth

- The second myth: Prisons are “factories behind fences” that exist to provide companies with a huge slave labor force

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#secondmyth

- The third myth: Releasing “nonviolent drug offenders” would end mass incarceration

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#thirdmyth

- The fourth myth: By definition, “violent crime” involves physical harm

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#fourthmyth

- The fifth myth: People in prison for violent or sexual crimes are too dangerous to be released

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#fifthmyth

- Recidivism: A slippery statistic

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#recidivism_measures

- The sixth myth: Reforming the criminal legal system leads to more crime

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#sixthmyth

- The seventh myth: Crime victims support long prison sentences

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#seventhmyth

- The eighth myth: Some people need to go to jail to get treatment and services

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#eighthmyth

- The ninth myth: Expanding community supervision is the best way to reduce incarceration

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#ninethmyth

- The high costs of low-level offenses

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#lowlevel

- Probation & parole violations and “holds” lead to unnecessary incarceration

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#holds

- Misdemeanors: Minor offenses with major consequences

- /reports/pie2023.html#misdemeanors

- “Low-level fugitives” live in fear of incarceration for missed court dates and unpaid fines

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#benchwarrants

- Lessons from the smaller “slices”: Youth, immigration, and involuntary commitment

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#smallerslices

- Beyond the “Whole Pie”: Community supervision, poverty, and race and gender disparities

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#community

- Each paragraph is also numbered, so you can use urls in this format:

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#paragraph1

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#paragraph2

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html#paragraph3

etc…

Acknowledgments

All Prison Policy Initiative reports are collaborative endeavors, but this report builds on the successful collaborations of the several versions of this report we have produced since 2014. For this year’s report, the authors are particularly indebted to Shan Jumper for sharing updated civil detention and commitment data, Emily Widra and Leah Wang for research support, and Ed Epping for help with one of the visuals. However, any errors or omissions, and final responsibility for all of the many value judgements required to produce a data visualization like this, are the sole responsibility of the authors.

We thank the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Safety and Justice Challenge for their support of our research into the use and misuse of jails in this country. We also thank Public Welfare Foundation for their support of our reports that fill key data and messaging gaps. Finally, we’d like to thank each of our individual donors — your commitment to ending mass incarceration makes our work possible.

About the authors

Wendy Sawyer is the Research Director at the Prison Policy Initiative. Along with helping direct the organization’s research priorities, Wendy is the author (or co-author) of several major reports, including Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, Beyond the Count: A deep dive into state prison populations, All Profit, No Risk: How the bail industry exploits the justice system and Arrest, Release, Repeat: How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems. Wendy also frequently publishes briefings on recent data releases, academic research, women’s incarceration, pretrial detention, probation, and more.

Peter Wagner is an attorney and the Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. He co-founded the Prison Policy Initiative in 2001 in order to spark a national discussion about mass incarceration.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. Alongside reports like this that help the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform, the organization leads the nation’s fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (a.k.a. prison gerrymandering) and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone industry and the video visitation industry. The organization also sounded the alarm in 2020 on the danger of COVID-19 outbreaks in prisons and jails, and has continued to provide data showing that state governments mismanaged the pandemic in prisons and jails and failed to ramp up early releases during COVID-19.

Footnotes

The number of state facilities is from the Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities, 2019, the number of federal facilities is from the list of prison locations on the Bureau of Prisons website (as of March 3, 2023), the number of youth facilities is from the Juvenile Residential Facility Census Databook (2020), the number of jails from Census of Jails 2005-2019 (counting facilities, not jurisdictions), the number of immigration detention facilities from Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Dedicated and Non Dedicated Facility List (as of October 11, 2022), and the number of Indian Country jails from Jails in Indian Country, 2021, and the Impact of COVID-19, July-December 2020. We aren’t currently aware of a good source of data on the number of facilities in the other systems of confinement. ↩

People detained pretrial aren’t serving sentences but are mostly held on unaffordable bail or on “detainers” (or “holds”) for probation, parole, immigration, or other government agencies. See the section on these “holds” for more details. ↩

These categories are not mutually exclusive; some people could be on both probation and parole, for example. See Tables 6 and 7 in the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Jail Inmates in 2021 — Statistical Tables. ↩

This is not only lens through which we should think about mass incarceration, of course. For instance, while this view of the data shows clearly which government agencies are most central to mass incarceration and which criminalized behaviors (or “offenses”) result in the most incarceration on a given day, at least some of the same data could instead be presented to emphasize the well-documented racial and economic disparities that characterize mass incarceration. It would be impossible to present all possible “views” of mass incarceration in one report, but we encourage readers to take inspiration from our approach here to create further “big picture” analyses that can help people better understand mass incarceration, its harms, and how to end it. ↩

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the number of people admitted to prisons; according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, “States and the BOP had 230,500 fewer prison admissions in 2020 than in 2019, a 40% decrease, because courts altered their operations in 2020, leading to delays in trials and sentencing of persons, and fewer sentenced [persons] were transferred from local jails to state and federal prisons due to COVID-19.” Absent dramatic policy changes, we expect that the number of annual admissions will return to near pre-pandemic levels as these systems return to “business as usual.” The data from 2021 suggest this is already well underway: the number of admissions increased enough from 2020 to 2021 to make up for about one-third of the drop in 2020. ↩

The number of annual jail admissions includes multiple admissions of some individuals; it does not mean 7 million unique individuals cycling through jails in a year. In a presentation, The Importance of Successful Reentry to Jail Population Growth [PowerPoint] given at The Jail Reentry Roundtable, Bureau of Justice Statistics statistician Allen Beck estimated that of the 12-12.6 million jail admissions in 2004-2005, 9 million were unique individuals. More recently, we analyzed the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which includes questions about whether respondents have been booked into jail; from this source, we estimated that of the 10.6 million jail admissions in 2017, at least 4.9 million were unique individuals. ↩

Like prison admissions, the number of annual jail admissions was dramatically impacted by the pandemic. Until 2020, the number of annual jail admissions was consistently 10 million or more. In the 12-month period ending June 30, 2020 (covering the first four months of the pandemic), admissions were down 16% from the year before, and by June 2021, they were down 33% compared to the 12 months ending in June 2019. Because these declines were not generally due to permanent policy changes, we expect that the number of jail admissions will return to pre-pandemic levels as law enforcement and court processes return to “business as usual.” ↩

The local jail population in the main pie chart (514,284) reflects only the population under local jurisdiction; it excludes the people being held in jails for other state and federal agencies. The population under local jurisdiction is smaller than the population (618,600) physically located in jails on an average day in 2021, often called the custody population. (For this distinction, see the second image in the first slideshow above.) ↩

The federal government defines the hierarchy of offenses with felonies higher than misdemeanors. And “[w]ithin these levels, … the hierarchy from most to least serious is as follows: homicide, rape/other sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny/motor vehicle theft, fraud, drug trafficking, drug possession, weapons offense, driving under the influence, other public-order, and other.” See page 13 of Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994. ↩

The felony murder rule has also been applied when the person who died was a participant in the crime. For example, in some jurisdictions, if one of the bank robbers is killed by the police during a chase, the surviving bank robbers can be convicted of felony murder of their colleague. For example see People v. Hudson, 222 Ill. 2d 392 (Ill. 2006) and People v. Klebanowski, 221 Ill. 2d 538 (Ill. 2006). According to a New York Times article, the U.S. is currently the only country still using the felony murder rule; other British common law countries abolished it years ago. A small but growing number of states have abolished it at the state level. ↩

For an explanation of how we calculated this, see “private facilities” in the Methodology. ↩

At yearend 2021, five states held more than 20% of those incarcerated under the state prison system’s jurisdiction in local jail facilities: Louisiana (49%), Kentucky (47%), Mississippi (34%), Utah (25%), and West Virginia (21%). For more on how renting jail space to other agencies skews priorities and fuels jail expansion, see the second part of our report Era of Mass Expansion. ↩

According to the most recent National Correctional Industries Association survey that is publicly available, an average of 6% of all people incarcerated in state prisons work in state-owned prison industries. However, the portion of incarcerated people working in these jobs ranges from 1% (in Connecticut) to 18% (in Minnesota). For a description of other kinds of prison work assignments, see our 2017 analysis. ↩

In 2022, a report by the ACLU and the University of Chicago Law School Global Human Rights Clinic found that very little has changed since then: Using a similar methodology, they found that prisons paid incarcerated workers a minimum average hourly wage of 13 cents and a maximum of 52 cents. ↩

In 2020, there were 1,155,610 drug arrests in the U.S., the vast majority of which (86.7%) were for drug possession or use rather than for sale or manufacturing. See Crime in the United States Annual Reports, 2020, “Persons Arrested” Table 29 and the Arrests for Drug Abuse Violations table (available for download here). In 2021, the FBI (which aggregates these data from local law enforcement agencies) began requiring all agencies to report data using the NIBRS system, and no longer accepted reporting through the Unified Crime Reporting program. While this switch was planned years in advance, this resulted in “a massive gap in information,” as almost 40% of agencies submitted no data in 2021, including those in large cities like New York and Los Angeles. Therefore, crime and arrest data from 2021 (and likely for the next several years) are less reliable than past years. One study comparing a sample of NIBRS data and data collected directly from the jurisdictions where crimes occurred found that over 13% of cases were “false negatives” and that “arrests may be underreported in NIBRS.” For that reason, we are reluctant to rely on the national arrest data from 2021. ↩

Despite this evidence, people convicted of violent offenses often face decades of incarceration, and those convicted of sexual offenses can be committed to indefinite confinement or stigmatized by sex offender registries long after completing their sentences. ↩

Some COVID-19 release policies specifically excluded people convicted of “violent or sexual offenses,” while others were not clear about who would be excluded. For example, Kentucky’s Governor commuted the sentences of 646 people but excluded all people incarcerated for “violent or sexual offenses.” New Jersey reduced its prison population by a greater margin than any other state, largely by passing a law to allow the early release of people with less than a year left on their sentences — but even this excluded people serving sentences for certain violent and sexual offenses. None of the 50 states or the federal Bureau of Prisons implemented policies to broadly allow the release of people convicted of offenses that are considered “violent” or “serious,” nor did they make widespread use of clemency or medical/compassionate release in response to the pandemic. ↩

The linked 2022 study found that a smaller portion of cities with “progressive” prosecutors saw increases in homicides compared to cities with “traditional” prosecutors (56% versus 68%) between 2015 and 2019, and the relative increase in homicides was lower in places with “progressive” prosecutors than those with “traditional” prosecutors (43% versus 55%). Another study by the Thurgood Marshall Institute at the Legal Defense Fund found no significant difference in pandemic-era increases in homicides between cities with “progressive” versus “traditional” prosecutors. ↩

In its Defining Violence report, the Justice Policy Institute cites earlier surveys that found similar preferences. These include the 1997 Iowa Crime Victimization Survey, in which burglary victims “voiced stronger support for approaches that rely less on incarceration, such as community service (75.7%), regular probation (68.6%), treatment and rehabilitation (53.5%), and intensive probation (43.7%)” and the 2013 first-ever Survey of California Crime Victims and Survivors, in which “seven in 10 victims supported directing resources to crime prevention versus towards incarceration (a five-to-one margin).” In a 2019 update to that survey, 75% of victims “support reducing prison terms by 20% for people in prison that are a low risk to public safety and do not have life sentences” and using the savings to fund crime prevention and rehabilitation. ↩

Many people convicted of violent offenses have been chronically exposed to neighborhood and interpersonal violence or trauma as children and into adulthood. As the Square One Project explains, “Rather than violence being a behavioral tendency among a guilty few who harm the innocent, people convicted of violent crimes have lived in social contexts in which violence is likely. Often growing up in poor communities in which rates of street crime are high, and in chaotic homes which can be risky settings for children, justice-involved people can be swept into violence as victims and witnesses. From this perspective, the violent offender may have caused serious harm, but is likely to have suffered serious harm as well.” Our report Reforms Without Results summarizes research findings that bear this out. ↩

Prisons are also entirely failing to provide people with adequate treatment. 43% of people in state prisons have a diagnosed mental disorder, yet at any given time, only an estimated 6% of people in state prisons are receiving professional help. And while half of people in state prisons had a substance use disorder in the year before their admission to prison, only 10% report having received any clinical treatment while incarcerated. ↩

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Probation and Parole in the United States, 2021, Appendix Table 7, 73,310 adults exited probation to incarceration under their current sentence; Appendix Table 11 shows 54,572 adults were returned to incarceration from parole with a revocation. The number of people incarcerated for non-criminal violations may be much higher, however, since almost 35,000 people exiting probation and parole to incarceration did so for “other/unknown” reasons. ↩

Like every other part of the criminal legal system, probation and parole were dramatically impacted by the pandemic in 2020 and 2021. In Probation and Parole in the United States, 2019, the Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that 90,477 adults exited probation to incarceration under their current sentence and 63,230 adults were returned to incarceration from parole with a revocation in 2019. In 2020, returns to incarceration for violations of supervision conditions (not for a new sentence) dropped by 25% for people on probation and 27% for people on parole. But because these declines were not generally due to permanent policy changes, we expect that the number of people incarcerated for non-criminal violations will return to pre-pandemic levels as correctional agencies return to “business as usual.” The data from 2021 suggest this is already happening: The number of returns to incarceration for violations increased enough from 2020 to 2021 to make up for about a quarter of the drop in probation returns and about half of the drop in parole returns observed in 2020. ↩

The percentage of people in jails held for misdemeanors changed during the first year of the pandemic, to a low of 17%, as many jurisdictions saw increases in serious crimes like assaults involving firearms, and as they had to prioritize jail detention for felony defendants whose cases were delayed by court slowdowns. However, by mid-2021, this trend was already starting to reverse, with people charged with misdemeanors making up 18% of jail populations. ↩

In 2019, more than half (61%) of juvenile status offense cases were for truancy. 9% were for running away, 8% were for being “ungovernable,” 9% were for underage liquor law violations, and 4% were for breaking curfew (the remaining 9% were petitioned for “miscellaneous” offenses). ↩

As of 2016, nearly 9 out of 10 people incarcerated for immigration offenses by the Federal Bureau of Prisons were there for illegal entry and reentry. We know of no newer source of detailed information about these offenses. ↩

People detained by ICE because they are facing “removal proceedings” and “removal” include longtime permanent residents, authorized foreign workers, and students, as well as those who have crossed U.S. borders. ↩

Several factors contributed to reductions in immigration detention, especially litigation and court orders that forced some releases, the use of public health law Title 42 to shut asylum seekers out at the border, and pandemic-related staffing issues at both ICE and Customs and Border Patrol. ↩

This program imposes electronic monitoring — whether through GPS ankle monitor or a mobile phone-based app — on individuals with little or no criminal history, and has expanded from 23,000 people under surveillance in 2014 to more than 293,000 people in February of 2023. ICE frequently updates its Alternatives to Detention program statistics in the Detention Statistics here. ↩