Proposed Biden junk fees rule provides lots of transparency but little protection for incarcerated people

We called on the Federal Trade Commission to strengthen its proposed rule to explicitly prohibit some of the most abusive junk fees.

by Mike Wessler, February 12, 2024

In 2023, with considerable fanfare, President Biden announced a new initiative to crack down on “junk fees” — those extra, often hidden charges that seem to do nothing besides jack up the price of a product or service while providing no extra benefit. At the time, we, along with 28 other groups, called on the President to put the junk fees harming incarcerated people and their families at the top of the list of things to be addressed.

As part of this initiative, the Federal Trade Commission recently released a new proposed rule to crack down on junk fees and asked for public comment. Last week, in collaboration with the National Consumer Law Center and our former general counsel, Stephen Raher, we submitted a 27-page comment explaining that these proposed rules will provide more transparency about junk fees but little actual relief for people entangled in the criminal legal system and their families.

Junk fees in the criminal legal system

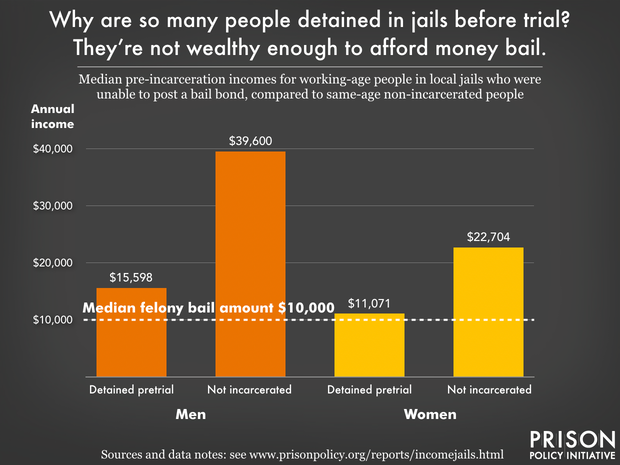

Junk fees are pervasive in all aspects of the criminal legal system, from arrest through after one’s release from detention. These harmful fees are particularly insidious because they’re generally unavoidable, and people in the system often have lower incomes and are less able to absorb these costs.

We’ve written at length about these fees in the past, but some of the most common and troubling ones are related to:

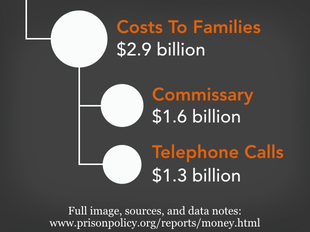

- Money transfers: Increasingly, prisons and jails are shifting costs for necessities, like food and hygiene products, onto the people they incarcerate. As a result, having access to money is increasingly important for people behind bars. However, because of the paltry wages incarcerated people earn, their loved ones often have to send them funds. When they do so, the private company the facility contracts with to handle these money transfers usually keeps a cut of the money for themselves. Sometimes that cut is more than 20%.

- Release cards: When a person is released, the prison or jail that confined them often puts any money from their trust account — wages, support from family, or funds they had in their possession when arrested — on a prepaid debit card. These cards are riddled with fees including for using the card, not using the card, or seeking customer service.

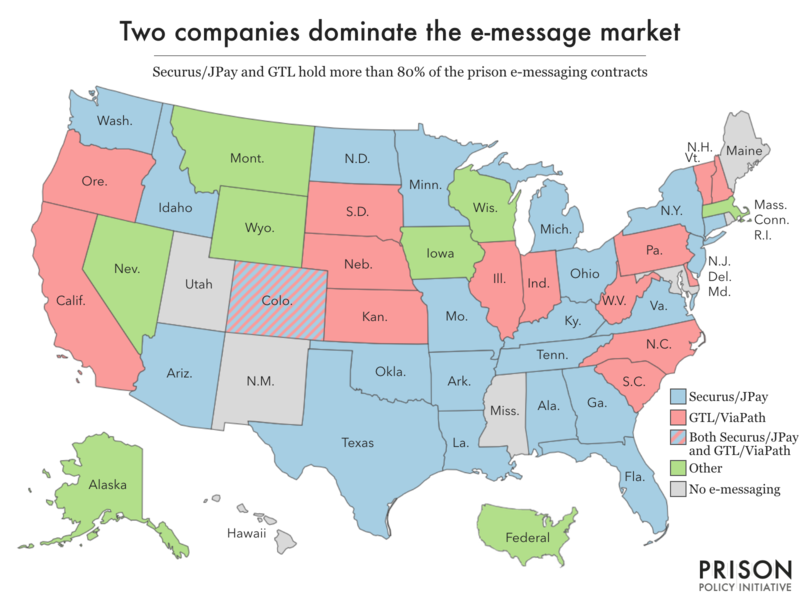

- Communication services: E-messaging and tablets have become nearly ubiquitous in prisons and jails nationwide. They’ve opened new opportunities for incarcerated people to stay in touch with loved ones and maintain connections to the outside world through books, music, and other services. They’ve also created a new way for the companies behind these services to sap funds from incarcerated people through opaque “infrastructure” or “maintenance” fees and bulk pricing schemes.

The proposed rule is good for transparency but not enough for incarcerated people

The rule proposed by the Federal Trade Commission primarily focuses on making these junk fees more transparent — rather than prohibiting them altogether. For those on the outside, they’ll no longer be surprised by hidden fees when they’re in the final stages of making a purchase. Companies will have to put these unavoidable extra costs front and center. This will make the true cost of a product or service easier to know up front, empowering consumers to make more informed decisions.

Unfortunately, transparency about these fees isn’t enough for incarcerated people and their families. While it is true they’ll be less likely to be surprised by hidden costs, under this rule, they still usually won’t have any way to avoid unfair fees. Unlike on the outside, people in prison and jail can’t use a different business if they think a company is loading a service with excessive fees. For money transfers, release cards, e-messages, and more, they are usually stuck with one company that the prison or jail contracts with to provide the service. Because incarcerated people are literally captive consumers who can’t take their business elsewhere, this type of transparency isn’t likely to reduce costs and abusive practices in any real way.

Giving the rule more teeth

The rule, as written, does not go far enough to protect incarcerated people and their loved ones from junk fees. Transparency isn’t enough; stronger enforcement and explicit prohibitions on certain practices are needed, too.

The good news is that the rule isn’t yet final. The Federal Trade Commission is currently considering comments like ours as they prepare their final rule, so it still has a chance to strengthen it to protect people in prisons and jails.

Here’s how we told the Commission they could strengthen the rule:

- Explicitly prohibit fees that provide little or no value to consumers: If a company charges a fee, there should be some benefit to incarcerated people. If not, it is simply a mechanism to sap money from them unfairly. While the rule currently relies on transparency to pressure companies to move away from these useless fees, more is needed.

- Ban junk fees that exceed the cost of providing a good or service: Many companies charge fees that significantly exceed their costs to provide the service. For example, some release card companies charge a $9.95 fee to close an account. This is far more than it costs the company to close the account, indicating it is just a way to get a little bit more money out of incarcerated people while they still can.